Pattern for Conquest

George O. Smith

Pattern For Conquest

By GEORGE O. SMITH

Illustrated by Kildale

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Astounding Science-Fiction March, April, May 1946.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

I.

The signal officer leaped from his position and made a vicious grab at the thin paper tape that was snaking from his typer to the master transmitter. It tore just at the entrance slot. The tape-end slid in; disappeared.

The master transmitter growled as the tape-end passed the scanner. Meters slapped up against the overload stop and two of the big rectifier tubes flashed over. Circuit breakers came open with a crash down in the power room, and up in the master modulator room the bell alarms rang, telling of the destruction of one of the tuning guides from overload peak.

The signal officer paid no attention to the damage his action had caused. He grabbed for the telephone and dialed a number.

"I want confirmation of messages forty-eight and forty-nine," he snapped. "What fool let 'em get this far?"

"What happened?" asked the superior officer mildly.

"I got forty-eight on the tape before I came to forty-nine," explained the signal officer. "I grabbed the tape just as it was hitting the master transmitter. The tape-end raised hell, I think. Default alarms are ringing all over the building. But who—?"

"It was my fault—I'll confirm in writing—that forty-eight was not preceded by an official sanction. You were quite correct in stopping them at any cost. As soon as the outfit is on the air again, send 'em both."

"Yeah, but look—"

"Orders, Manley."

"I'll follow 'em," said Signal Officer Manley, "but may I ask why?"

"You may, according to the Book of Regs, but I'm not certain of the reason myself. Frankly, I don't know. I questioned them myself, and got the same blunt answer."

"The whole terran sector has been slaving for years to keep this proposition from happening," grumbled Manley. "For years we have been most careful to stop any possible slipup. Now I find that the first time it ever gets down as far as my position and I leap into the breach like a hero, I'm off the beam and the stuff is on the roger."

"I'll give you a Solar Citation for your efforts," offered the superior ruminatively. "I know what you mean. We've been trying to keep it from happening by mere chance. And all of a sudden comes official orders, not happenstance, but ordering it. Let's both give up."

"The gear is on the air again," said Manley. "I'll carry on, like Pagliacci, roaring madly to our own doom. But first I'm going to have to restring the master. Shoot me a confirm, will you? I don't expect to use it, but it'll look nice in some time capsule as the forerunner of history."

Within a minute messages forty-eight and forty-nine were through the machine, up through the master modulator room and out in space, on their way to Mars and Venus, respectively.

The Little Man looked up at Co-ordinator Kennebec. The head of the Solar Combine looked down with a worried frown. This had been going on for some time. The Little Man had been, in turn, pleading, elated, demanding, mollified, excited, and unhappy because the ruler of the Solar Combine could not understand him fully. He was also unhappy because he could not understand the head man's meaning, either.

The Little Man had three cards in his hand. He was objecting violently, now. He was not angry, just positive of his desire. He put two of the cards on the desk before Kennebec, and agreed, most thoroughly, that these were what he wanted. The third card he tossed derisively, indicating negation. This one was of no use.

Kennebec shrugged. He picked them up and inserted the unwanted card between the other two. He did it with significance, and indicated that there was a reason.

The Little Man shrugged and with significance to his actions, accepted the three. If he could not have the two without the third, he'd take all three.

He saluted in the manner that Kennebec understood to be a characteristic of the Little People's culture. Then he turned and left the office, taking with him the three cards.

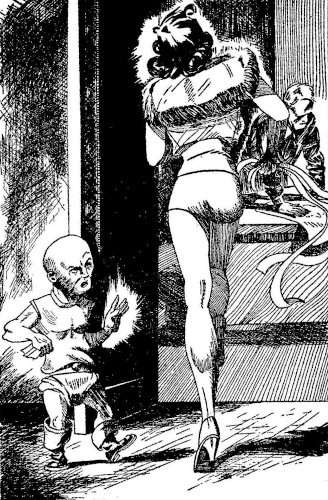

As he opened the door, he was almost trampled by Kennebec's daughter, who was entering on a dead run with a bundle of transmitter tape trailing from one hand. Patricia looked down, made a motion of apology to the Little Man, whose head came just even with her hip, and then turned to her father as the Little Man left the scene.

"Dad," she said, "here are press flashes from Mars and Venus. Singly, either one of them pleases me greatly. Simultaneously I can't take it."

"Sorry, Pat. But this isn't a personal proposition."

"But it means trouble."

"Perhaps."

Patricia snorted. "It does mean trouble and you know it. How are you going to avoid it?"

"I'm going to assign Flight Commander Thompson to the task of keeping or combing them out of one another's hair."

"And if and when he's successful," smiled Pat derisively. "I assume that Thompson will be awarded the Solar Citation for bravery and accomplishment far above and beyond the call of flesh?"

"He'll have earned it," smiled Kennebec. "Let's see what the sister worlds have to say."

"Not much—yet. Neither one of them seems to be aware of the other's action—yet. I'll bet the Transplanet Press Association wires will be burning when they all find out."

"TPA is going to suppress any word of dissension," said Kennebec.

"Um-m-m—seems that Terra, as usual, has a bear by the tail. Why couldn't he have picked less dangerously?"

"Knowing nothing of the Little People's culture, I can't say. I don't even understand him most of the time excepting that I have attained the idea that something is very important and must be done immediately. What it is I don't really know, but I gather that it concerns the integrity of a number of stellar races including that of the Little People."

"Sounds like corny dialogue from a bum soap opera," said Patricia. "It's a sorry day for civilization when it must depend upon a deal like this."

"I'm certain that they understand. The Little Man reviewed the records. Given the apparent understanding of mere records that he has—in spite of not being able to understand me or any other Solarian—he must know that we're all playing fireman in a powderhouse. He is going on through with it in spite of what he must certainly know."

"I feel inclined to take a vacation at Lake Stanley or Hawaii until this blows over."

Kennebec laughed. "It won't be that bad, and besides, you're a part of this and no matter where you go, you'll be in it. Might as well give up, Pat. You can't run now."

"I know," answered Patricia wistfully, "but I'd like to keep out of the way of any flying glass."

Stellor Downing was Martian by birth and by six hundred years of Martian-born forebears. His family could trace its line back to the first group of Terran colonists that braved the rigors of Martian life before technology created a Martian world that was reasonably well adapted for human life.

Downing, being of hard nature, cold and calculating, and murderously swift, should probably have been dark and swarthy with beetling brows and a piercing stare.

But Downing lived on Mars, where in spite of the thin atmosphere, Sol's output was low. Downing had light hair, a skin like the baby-soap ads, and pale-blue eyes that looked as innocent.

A lot of people had been fooled—but not Martians.

Stellor Downing's rapid rise up through the ranks of the Solar Guard was legendary on Mars. His swinging gait was more or less known to all theater-going Martians, and the sound of his voice over the radio was familiar. He wore a double modine belt, with one of the nasty weapons on each hip—where they crossed over his stomach, a dull silver medallion held them together.

The medallion was the sharp-shooter's award.

Stellor Downing came on the spaceport escorted by six or seven officials. He talked with them until it was time for take-off. Then they all became more serious.

"We have no idea what this mission is," said one. "But if you do it honor, you'll get that other star."

"That'll make you a Flight Co-ordinator," added another.

"I can't make any promises," said Downing. "I'll do my best."

"Terra must be really in a hole to call on you," laughed a third. "You're by and far the best flight commander in the Guard."

Downing lifted his eyebrow. "I'll admit that I'm not the worst," he said cheerfully. "I hope you're right about the other." He turned to his orderly and gave a sign. The orderly lifted a whistle and blew a shrill note that cut the thin air of Mars.

Three hundred men entered twenty-five ships, and the spaceport was cleared. Radio messages filled the ether, as the ships were checked before take-off. Then as the clamoring of the radio died, a more powerful transmitter in the flight commander's ship gave the order to lift.

The center ship, bearing the red circle of Mars with the five stars ringing it, lifted first, followed by the next concentric ring of ships.

The third ring followed in close formation and then the last. In a great space cone, the flight closed into tighter formation and streaked straight upward and out of sight.

Stellor Downing was on his way to Terra.

Flight Commander Clifford Lane was driven onto Venusport in a cream-colored roadster that was either spotless enamel or mirror-finish chromium as far as the eye could reach. In the car with Cliff Lane were four women whose glitter was no less flagrant than the car's. The slight olive-tint to their skin made their very white teeth flash in the sunshine as they smiled at their passenger.

This was Venus—living at its highest temperature. The car rolled to a stop beside Cliff Lane's command and they all climbed out. It was with a generous display of well-browned skin.

Lane's costume was no less scanty than the women's. The modine over his right hip was chased with silver and engraved, the holster was hand-tooled and studded with five small emeralds.

"What are you going for?" asked one of the women.

"Don't you know?" teased the one beside her. "Cliff is going to Terra to court Patricia Kennebec."

"I think we should kidnap him."

"You'd be sorry," laughed Cliff, waving the official order in front of her.

"Maybe we can bribe him. Tell you what, Cliff, you get this job done and you'll probably get a promotion. If you do, we'll all chip in and get that insignia on your modine holster changed to six full stars. But to do it you'll have to come back to us—single."

Cliff laughed. "And if it takes me more than six months, you'll all be off elsewhere."

"But what's Patricia got that we haven't?" wailed one.

"Him," grinned another.

"No, we've got him—now."

"Any time someone wants something else, you might as well give it to them, because they'll get it one way or another."

"Look, kids," interrupted Lane, "we've been talking this up and down for three hours. Now it's time to take off. Scram, like good little lovelies."

Cliff bade them a proper good-by and herded them back into the car. It started and rolled slowly away amid feminine calls. Its course was erratic, for the driver was handling the car by instinct; her head being turned back over the front seat to watch Lane, too. Had she been on a road instead of a broad, shining expanse of tarmacadam, trouble would have met her more than half-way.

Cliff waved a last good-by and turned to face a group of kine-photographers. "Hi, Hal. Hello, fellers."

"Hey, Cliff, will you wipe your puss or don't you care if Venus sees their Favorite Son in lipstick?"

Lane laughed and wiped. "On me it doesn't look good," he agreed. "What'll you have?"

"We'd like shots of you giving the last order, entering the ship, and then wait until we can get set up on the edge of the field. We want a pan shot of the command hitting the ether."

"O.K. That we can do."

He turned to the group of unit commanders and said, "The usual, fellows. Straight up and away. Hey, Hal, pan the gang, will you? As a hotshot I'm slightly cool if they aren't behind me."

"Great stuff," grinned Hal. The kinephotogs spread out, took their shots, and then closed up for the final order. As the space door clanged shut, they raced for the edge of the field and waited.

With an instantaneous rush, the lead ship, bearing the green triangle of Venus surrounded by the five stars of the flight commander, took off in a slight swirl of airswept dust. Then at a separation of exactly three tenths of a second, the other twenty-four ships leaped into the sky and formed a long spiral in space.

The specks that were lost in the sky were Clifford Lane and his command heading for Terra.

II.

The Little Man had a name. Once in his own tiny spacecraft and surrounded by his cohorts, he was addressed in his own semi-speech, semimental means of communications.

"You have succeeded, Toralen Ki?"

"As best I can."

"Not perfect?" asked Hotang Lu.

"As long as the lack of communications exists, there can be no transfer of real detailed intelligence between the two races. They have no mental power of communication at all, of course, and since we use our mental power when we wish to carry over a plan or abstract thought, we fail when we are confronted as we are now. There are no words in our audible tongue that have the proper semantic meaning."

"But you did succeed in part?"

"I have succeeded so far as gaining their co-operation. They will assign to me or to us, rather, the necessary personnel and material to complete the task."

"Then we have succeeded."

"In a sense. To carry this concept over was most difficult. As long as we have their consent, everything will work out in time."

"You have succeeded in convincing them that the Opposites must be used?"

Toralen Ki smiled. "The Opposites we picked are violent enemies."

"Good!"

"It could be better. I'd hoped that they would be mere opposing personalities. It is not necessary that people of opposite personality be bitter rivals for everything."

"But the greater the opposing forces, the greater the strength of the mental field."

"In this case," said Toralen Ki thoughtfully, "they insist upon including a third party, of equal rank, to act as referee, or mediator. It will be his task to keep the Opposites from fighting one another."

"They were quite concerned?"

"Definitely. It was most difficult to convey to them the fact that the future of their—and all, for that matter—race depends upon absolute co-operation between the mental opposites we have picked."

"Once the suppressor is destroyed, communication with this race will be easy. Then they can be told."

Toralen Ki shook his head. "Fate is like that. To carry out the plan properly, they must co-operate. In order to tell them what they must do, the suppressor must first be destroyed. And were it not for the suppressor in the first place, the mental capability of this race would require no assistance from the like of you and I or any other member of any other race. The Loard-vogh were very brilliant, Hotang Lu. To hurl suppressors of mental energy through the Galaxy was a stroke of genius."

Hotang Lu smiled sourly. "I suppose it is a strange trick of fate to have the fate of the entire Galaxy hanging upon an act of co-operation between two bitter rivals. Especially when the means to explain fully also hangs upon the outcome of their co-operation. I am reminded of an incident in my boyhood. I sought work. I had no experience. They wanted men with experience. In order to get the experience I must work—but they wouldn't put me to work without experience. But it will be easier once the initial step is taken," said Hotang Lu.

"I know it will. It will be so much easier once they understand our motives, at least. Had they proved non-co-operative, we would have been completely stopped. As it is now, we can foresee the proper culmination of all of our plans. We will win, yet!"

"To our ultimate victory," said Hotang Lu, taking a sip from the tall tube before him. Toralen Ki followed the other, echoing the words.

"It is fortunate that they have evolved as far as they have," said Toralen Ki, after the toast. "Dealing with a completely ignorant race is more difficult. These people have a proper evaluation of technical ideas. Therefore they will understand the proper course without having it forced down their collective throats."

"With their already available knowledge of the super drive, it indicates their ability. Have they colonized any of the nearer stellar systems yet?"

"Several. But the urge is not quite universal, yet. Only the adventurers and the malcontents seem to go. They will spread though, if they're not stopped within a reasonable time."

"Time.... Time—" muttered Hotang Lu. "Always time. Must we fight time forever?"

"Fighting time is most difficult when you are behind," remarked Toralen Ki. "When you are ahead, it is no longer a fight."

"We must move swiftly and yet we can do nothing to cause haste. Confound it, must a man always be pinched between the urgency and the impossible?"

"Certainly. It makes one feel the ease of life during the times of no-stress."

"Some day I hope to see a period of no-stress that is longer than one tenth the duration of the trouble before and after it."

"You may," smiled Toralen Ki. "But there will be no after."

"Gloomy thought. I'll forget it, thank you. But to change the gloomy subject, I suggest that we contact Tlembo and let our ruler know that we have, in part, been successful."

"Right. I wish we were artists. So much can be conveyed to others by mere pictures."

Hotang Lu shook his head. "How could you possibly sketch the operation of a suppressor? Perhaps they could do it, for they seem to have advanced the art of thought-conveyance through pictures to a high degree. But recall that no Tlemban ever considered the art a necessary one and so we lack the technique."

"I know."

"After we contact Tlembo, when can we say we are to start?"

"I think they convey something about two days. We await the arrival of the contingents from the other planets."

"More time wasted."

"Think of the eons before this and the eons that will follow. And then think of how utterly minute your two days are. They will arrive, but quickly enough."

Flight Commander Cliff Lane heard the recognition gear tick off, and he whirled to look at the scanning plate. "The devil," he growled.

"Sir?

"What is he doing here?"

"I don't understand, sir."

Cliff smiled wryly. "Sorry. I thought this would be more or less pleasant."

"Isn't it?"

"That trace," he said, pointing to the squiggle on the scanning plate, "happens to be the recognition trace of no one other than Stellor Downing."

"Oh," said the orderly. "I didn't know."

Lane grinned. "Then you're the only one that doesn't. Any of the rest of this outfit know it on sight. Take a good look at it, Timmy, and the next time you see it, do your best to do whatever that is doing, but do it quicker, neater, and with more flourish. Understand?"

"Yes, sir."

Lane strode into the operations room, and looked over the plotter's shoulder. "What's he doing, Link?"

Lincoln made some calculations on a paper, plunked the keys on his computer for a moment and then came up with an equation. He showed it to Lane with a grimace.

"Landing," said Lane cryptically.

Lincoln nodded.

"Can we beat him in?"

"I think so—if we get the jump on him."

"There are just two landing circles on Mojave that aren't dusty," said Lane. "One of them is not far from the field office building. The other takes a full hour of travel before you can check in. I don't like to walk."

"Right. I'll see what we can do."

"Good."

One-tenth of a light-second away, an aide entered Stellor Downing's cabin. "Recognition, sir," he said. "Flight Commander Lane, from Venus. I thought you'd like to know."

"What's his course?" clipped Downing.

"Mojave."

"Tell the tech to drop interferers. Tell navigator to correct course for blitz-landing, and tell pilot to streak for landing Circle One. Also broadcast crash-warning."

"Right. We're going in if we have to collide to do it, sir?"

"We'll have no collision. Lane wouldn't care to scrape any of his nicely painted little toys."

"On the roger," said the aide, leaving immediately.

Two flights of ships changed course.

Down on Mojave, in the control and operations tower, signal officer Clancey's face popped with beads of cold sweat. He sat down heavily in a chair and:

"Tony! Get me the chief!"

"What's wrong, sir?" asked Tony.

"This desert ain't a big enough landing field to take on Lane and Downing. Not all at once."

"Lane and Downing!" Tony streaked for the telephone. He called, and handed the phone to Clancey, who plugged it into his switchboard, putting it on his own headset so that he could hear both the chief and the operations.

"Chief. Look, this is too hot to handle. Lane and Downing are both heading for Mojave."

"I know."

"Do you?" asked Clancey sarcastically. "They're heading for Mojave. They're racing for Number One. And they're due to arrive within three or four milliseconds of one another!"

"Hell's Rockets!" exploded the chief. "Get 'em on the air and tell 'em they're under orders."

"There isn't any air. One of 'em dropped interferers."

"Official?"

"Unofficial."

"O.K. Record the fact and then go out and watch. It's out of your hands if they can't hear you. As long as you have a record of interference it's not your cookie. It belongs to them."

"Mind if I head for a bomb-shelter?" grinned Clancey.

"Oh, they're both smart. That's one fight that never hit an innocent bystander."

"—yet," added Clancey.

"Well—?"

"It might be the first time I died, too," objected Clancey.

"You don't want to live forever, do you?"

"Wouldn't mind."

"Nuts. There must be something good about dying. Everybody does it."

"But only one; never again."

"Well, play it your way. I sort of wish I could be there to watch, too."

"Just tell mother I died game. So long, chief. I hear music in the air right now, and hell will pop directly."

Like twin, high-velocity jets of water, the two space flights came together, rebounded off of their individual barrier-layers and mingled in a jarring maze of whirling ships. In a shapeless pattern they whirled, and they might have whirled shapelessly all the way to Mojave, except for one item.

From Downing's lead ship there stabbed one of the heavy dymodine beams, its danger area marked with the characteristic heterodyne of light. It thrust a pale green finger into the sky before it, and as it came around, the other ships moved aside. That was the breaker. The flights reformed into twin interlocked spirals that thrust against one another with pressors and tore at one another with tractors in an effort to break up the other's flight.

Lane snapped: "That's a stinking trick."

"He's warning—"

"Oh, nice of him to heterodyne it. I wish I had a roboship. I'd drive it into his beam and tell him that he clipped my men—"

Stellor Downing grinned at his unit commander. "I told you he'd duck," he said loftily.

"Wouldn't you?"

"Nope. I'd drive into it and see if he'd shut it off before I hit it."

"Supposing he didn't shut it off?"

"Don't ask me," said Downing. "If he did, it would be to spare the men with me. If I ducked at the last minute, it would be for the same reason. If we were alone, I wouldn't dive into a beam—but we might try a bit of rivet-cutting."

The unit commander's face whitened a bit. That was an idea he disliked. And yet some day he knew they'd get to it. Just as practically everybody knew it.

The hard ground of Mojave whirled up at them, and the twin spirals flattened out. Like a whirling nebula, they spun, slowing as they dropped.

Clancey groaned from the top of the tower: "There ain't room for fifty ships in Circle One. There ain't room for six ships fighting one another. Holy—"

The spattering of force-beams, tractor and pressor, died as the last hundred feet of altitude closed in. The ships, still wabbling slightly, slowed their spinning around and curved to drop vertically for fifty feet.

The ground shook—

And there was left but one dustless landing circle at Mojave—the other one.

Windows in the control tower cracked, a fuse alarm rang furiously, and somewhere a taut cable snapped, shutting off the fuse alarm for lack of juice. The lights went out all over the Administration Building, and every ceiling dropped a fine shower of plaster freckles.

They landed on empty desks and open chairs.

Seven thousand employees of Mojave were crammed out on the view-area, wiping the dust from their eyes and shaking their heads.

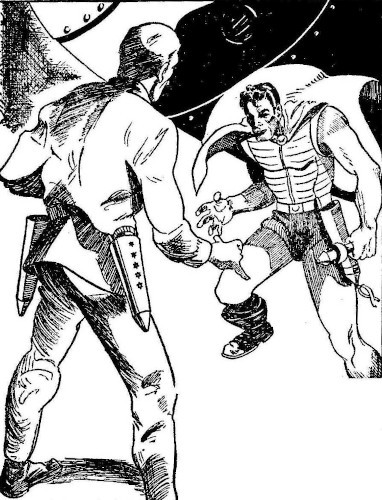

And through the dust, weaving their way between the ships of either command. Cliff Lane and Stellor Downing advanced upon one another.

Out of a cloud of dust came Lane. Downing emerged from the other side and faced the Venusite.

"You fouled me," snarled Downing.

"Who, me?" asked Lane saucily.

"I broadcast a crash-warning."

"You should have done it before you dropped interferers. All I know is that you disputed my course."

"So I did. So what?"

Lane reached for a cigarette. He did it with his left hand, though he knew that Downing wouldn't draw his modines while either hand was occupied. Downing was fair, anyway. "So you didn't get what you wanted—again."

"Neither did you."

"All right. Are you happy? Got to have the best, don't you?" growled Lane. "Can't stand to see anybody take even a toothpick that you can't have two of."

"If you were more than a drug-store cowboy ... brother, what a get-up."

Lane flushed. "My clothing is my own business."

"It's very fetching. Chic, even."

"Shut up, dough-head. I'm not forced to wear an iceman's uniform so people won't think—"

"What's the matter with me?" gritted Downing.

"You might at least put on a clean shirt," drawled Lane, tossing his cigarette at Downing.

"Oh, swish—"

That did it. Lane's right hand streaked for his hip after a warning gesture. Downing's two hands dropped and came up with the twin modines.

Only a microtime film record would ever tell the quicker man. Their weapons came up and forward and the dust of landing Circle One was shocked with a sharp electrical splat.

III.

"And that's your job, Thompson," said Kennebec.

"And that's enough," responded Thompson. He wiped his face.

"Oh, I'll issue the proper orders. They'll receive them—and any trace of insubordination on the part of either of them will be cause for reprimand. Public reprimand."

"But the reason behind all this? I don't understand."

"Nor does anyone else. Look Thompson, the Little Man has a super ship out there on Mojave. It is a real bear-cat. Packed into space smaller than this office is enough stuff to hold off the Guard for a week. That's premise number one.

"Number two. They have some sort of telepathic means of communications.

"Number three. They came here for help. Why, I may never tell you until it's analyzed by the experts. But they came here for help. A machine, bomb, some means of hell and destruction or other must be destroyed. It must be located, too. Using some means of analysis on our card files, voice records, identification quizzes, and so forth, they decided upon Lane and Downing as the mainsprings. They'll have none other. Now why or wherefore isn't for me to decide. If they want Lane and Downing, they'll get Lane and Downing and none others. At the very least, we've got to play their game as long and as well as we can play it. I want to have the Solar Guard equipped as well as that ship is, and this is the way to do it."

"Why don't they go out and destroy this thing themselves?" asked Thompson.

"I wouldn't know. You know as much as I do."

"They may fear the cat race."

"If I had their stuff, I'd fear nothing."

The telephone rang and Kennebec lifted it. He listened and then hung up slowly.

"Your job—" he said. "Lane and Downing are making a running fist fight to see who lands on Circle One. If you go a-screeching fast, you might be able to make it by the time they hit."

"Right—" and Thompson left unceremoniously.

He hit the street, landed in his car, and was a half block away, siren screaming, before he realized that he had a passenger. It was Patricia.

"Huh?" he asked foolishly.

"Well, the engine was running, wasn't it?"

"I didn't notice."

"Fine thing."

"You must have heard."

"Who hasn't. Come on, Billy. A little more soup. I know that pair and they won't waste time."

Thompson poured more power into the car and it increased in speed. The way was cleared for him, though it took some expert driving to cut around and through the traffic, stopped by the demanding throat of the official siren.

Thompson roared up the main road to Mojave, sent the guard-rail gates flying dangerously over the heads of onlookers, and sped out onto the tarmacadam. The dust of the rough landing was just starting to rise as Thompson slid into the outskirts of the circle of ships. His car skidded dangerously on locked wheels, and he used the deceleration of the vehicle to catapult himself forward. He landed running and disappeared into the circling dust.

He could be certain that Lane and Downing would be at the center of this whirling mass.

Lane blinked. Downing shook his head in disbelief. Both recharged their modines and—

"That's about enough!" snapped Thompson, coming through the dust. "You pair of idiots."

They whirled.

"No, you didn't miss, either of you." He waved his own modine. The aperture was wide open. "But I've got a job to do and you aren't going to spoil it on the first try. I'd hate to report to Co-ordinator Kennebec that I'd failed—doubly. And that all there were to his plans were two hardly scarred corpses."

He tossed his weapon on the ground and nursed his hand.

"You're the fool," said Downing. "Don't you know you can't absorb the output of three on one of 'em?"

"I did," snapped Thompson. "Though I'd rather use a baseball bat on both of you."

"We didn't intend to hurt anybody," explained Lane.

"Good. Now that that's over, you might play sweet for a while, doing penance for burning my hand."

"You mean we're going to work together?" asked Lane in disbelief.

"And you're going to act as though you liked it."

"I won't like it," scowled Downing.

"Just make it look good. You've got a job to do, and once it is done you can go rivet-cutting for all I care."

"It's an idea."

"All right. But listen, you pair of fools, Patricia is coming through this haze you kicked up. Take it easy."

"Pat!" it was a duet.

"Yeah, though you should both call her Miss Kennebec after this performance."

"You leave her out of this," snapped Lane.

"After one more statement. You fellows can fight all you want to, but remember, if you're fighting for Pat, just consider how she'd feel to A, if as and when A chilled B to get rid of B's competition. Now let's behave ourselves—and if you're asked, this was a fine shindy; a real interesting whingding."

Clancey saw the four of them emerge from the aura of dust and he held his head. "Look at 'em, chief. It ain't goin' to last. I know it ain't. Mis's Kennebec holding an arm of each of them and Mr. Thompson chatting to all three from behind."

"Clancey, this may be the calm before the storm. But from what I hear, both of them will be a long way from Sol when the tornado winds up. They're heading for the Big Man's office right now. He'll tell 'em."

"I think I get it," said Lane. "He wants us to analyze it. That's why this motion of our heads to the thing."

"You may be right."

"This is a long way from here, though. I don't quite get it."

Kennebec explained his reasons for playing the Little Man's game.

"O.K., chief. I've heard of this cat race," said Downing.

"You have?"

"Only malcontent rumors. Tramps, adventurers, and the like are inclined to take runs like that for the sheer loneliness of it—and the desire to set foot where no man ever stood before. It's about the limit of run with even a Guard ship. I suppose any rumors can be discounted, but I've been given to understand that they are a rather nasty kind of personality."

"Being cats they would be," added Lane.

"Not necessarily," objected Thompson. "We are basic primate-culture, but we don't behave like apes."

"No?" asked Kennebec with a sly smile.

"O.K."

"Now," said Kennebec. "They've chosen you two for the job in spite of our explanations that you are slightly inclined toward dangerous rivalry. Why they insist I do not know. Be that as it may, gentlemen, you have this project. You have twenty-five ships each, all armed to the best of Solar technique. You'll have to play it close to your vest, I gather, since this machine or bomb is at present running through their system. Therefore I order you, officially, to refrain from any competitive action until this project is completed. The Little Man has detectors to locate the thing, you'll each get one of them. Track it down and analyze it. Destroy it after you could reproduce it. Thompson, your only job is to remind this pair of worthies that their prime job is to finish this project."

"It may be not too hard," smiled Thompson. "I won't have any trouble."

"Look, Downing, if this thing is as important as they claim, we're fools not to work together. Right?"

"As corny as it sounds—the fate of races depends—I believe the Little Man. Until this fool project is over, no fight."

"Shake."

Downing made a "wait" gesture. He picked up an ornate dinner candle from the mantelpiece and lit it. He took cigarettes, offered one to Lane, and they shook hands. And they lit their cigarettes in the same candle flame.

And Thompson said to Kennebec: "A pair of showmen."

"And the best flight commanders in the Guard, confound it!"

Stellor Downing, out of his Martian uniform and wearing the dress uniform of Terra, piloted Patricia Kennebec through the tables to a seat. "Stop worrying," he laughed.

"I suppose I should," she admitted.

"Then please do."

"I will. It isn't complimentary to you, is it?"

"I wouldn't worry about that."

"All right. But I still think I'm fostering trouble for both of you."

"By coming out with me tonight? Lane asked—but he was late. He can't object to my making plans first, can he?"

"He admitted that he had only himself to blame."

"Then?"

"But I can't help thinking that I'm the cause—"

"Look, Pat. Analyze us. Cliff is Venusite. His family went to Venus about six hundred years ago—probably on the same ship that mine left for Mars on at about the same time. Lane's impetuous and slightly wildman. I'm more inclined to calculate. Dance?"

"Yes—that was a quick change of subject, Stell. How do you do it?"

"The music just started—and my basic idea in coming here was to dance with you."

"How about ordering? They'll get the stuff while we're dancing."

"Everything's ordered," he smiled. He drew back her chair, offered her an arm, and led her to the dance floor.

Downing's dancing was excellent. He was precise, deft, and graceful despite his size. The orchestra finished the piece, and then with a drum-roll introduction led into the classic "Mars Waltz."

The step was long and slow and though some of the other couples drifted off the floor to await something more springy, they finished the long number with a slight flourish.

Another drum-roll, and: "Ladies and Gentlemen," said the announcer, "that number was in honor of Stellor Downing, number one Flight Commander of the Martian sector of the Solar Guard!"

There was a craning of necks to see the Martian, and Downing politely saluted before he retreated to his table.

"And in this corner ... pardon me, I mean over here, ladies and gentlemen, we have Clifford Lane, the top Flight Commander of the Venus sector!"

The necks swiveled like the spectators at a tennis match and the spotlight caught Cliff, standing at the door with a woman on each arm.

At a word from the manager, four large, square-shouldered men in tuxedos accepted two tables. Base lines for defense—

But Lane merely nodded affably in the bright spotlight. "Thanks, and now, professor, that light is bright. Play, George. The Caramanne if you please."

"But I can't dance the Caramanne," objected the girl on his right.

"And I wouldn't dance it in public," said the girl on his left.

"Well, we all know someone who can and will," laughed Cliff. He led them to Downing's table, shook hands with Stellor and underwent a ten-second grip-trying match. He introduced them all around and then asked: "Downing, may I steal her for a moment? I think she's the only one present that can hang on while I take care of the Caramanne."

"For a moment," said Downing.

The four men in tuxedos blinked and shook their heads. The manager took a quick, very short drink. It was a draft of sheer relief.

The pulse-beating rhythm of the native dance of Venus started with rapid tomtom, and then carried up into the other instruments. With the floor to themselves, Cliff and Patricia covered most of it in the whirling, quick-step.

"A fine specimen of fidelity you'd make," she laughed.

"Well, you were busy. I had to do something."

"You seem to do all right. They're both rather special."

"Know them?"

"Only by nodding acquaintance."

"Well, any time you have time to spare for Cliff Lane, just let me know and I'll toss 'em overboard and come running."

"And in the meantime?"

"And in the meantime, I'm not going to rot."

The dance swung into the finish, which left them both breathing hard. Lane escorted Patricia back to the table, where Downing sat silent. As they came up, a third man approached. Lane seated Patricia and then greeted the new-comer.

"Hi, Billy. Lucky, we've got a girl for you, too."

Thompson breathed out. "Oh," he said surveying the situation. Both situations looked him over and smiled. "Lenore, and Karen, this is Billy Thompson. He's in division."

"Which division?" asked Lenore.

"Subdivision," grinned Thompson. "I'm the guy they got to comb these guys out of each other's hair."

"Poor man," sympathized Karen.

"You gals match for him," laughed Cliff. He tossed a coin.

"Heads!" called Lenore.

"You lose—take him," chuckled Lane.

Lenore put her arm through Thompson's. "Nope," she said brightly, "I win."

The spotlight hit the table. "We might as well finish this," laughed the announcer. "I present the referee ... pardon me, folks, I mean the top man of the Terran sector; Flight Commander Billy Thompson!"

The music started, and all three couples went to dance to a medley of Strauss' waltzes.

IV.

"It was all sort of whirligig, like," explained Patricia. "We didn't get home until along toward the not-so-wee large hours of the morning."

"I know," responded her father dryly. "The whole gang of you were raiding the icebox at five."

"The rest of them left shortly afterward."

"All of them?"

"No, Stellor outsat them and lingered to say goodnight."

"What do you think of Stellor?"

"I've always thought highly of Stellor. He's got everything. He knows what he wants and he knows how to get it."

"And Cliff Lane?"

"Cliff is strictly on the impulse."

"I wouldn't say that," objected her father. "After all, both of them got where they are because of their ability."

"Well, Cliff gives the impression that he just thought of it."

"Of what?"

"Of whatever he was going to do next."

"A good thing nobody ever asked you to decide between them."

"It would be difficult."

"Well, it won't be necessary. They're leaving after the next change of watch."

"So soon?"

"The Little Man gave the impression that all of us were fighting for time."

"I see. You do believe that this is important?"

"I can see no other reason for it."

"Um-m-m. Well, I'll be down to see them off."

"All of us will."

"I was worried, last night. I could see a beautiful shindy in the offing."

"And it didn't get bad at all?"

"No," answered Patricia in surprise. "I think Cliff saved the day by showing up with a couple of women. I wouldn't have wanted to sit between the two of them all by myself. That would have been strictly murder. And I wouldn't have wanted to see Stellor off without saying farewell to Cliff. Stellor got here first with the plans—I was strictly a fence. I didn't know what to do. So I did it. And everything turned out fine."

"You can hope that it will always turn out fine. What'll you do if one of them turns to some other woman?"

Patricia laughed wryly. "I'd lose both of them, Dad. Believe me, I would. The other would barge in and set sail for the woman just as sure as I'm a foot high."

"But ... but ... but—"

"I don't really know—nor do I care too much."

"Anticipating me? You mean you don't know which one really wants you and which other is just here for sheer rivalry?"

Patricia nodded. "They don't, either," she said sagely. "It is a good thing that we have time. Time will out, as you've always said. Time will get us the answer. Right now I'm neither worried about time, or even not having my mind made up on a future. I've got a number of years of fun ahead before then."

"Bright girl," laughed Kennebec. "Now let's get going. We want to see them off, don't we?"

Two hours later, seventy-five of the Solar Guard's finest ships arrowed into the sky above Mojave. In the lead, determined by a toss of the coin, was Stellor Downing's command. Thompson's outfit, running to his own taste, encircled the Downing cone at the base in a short cylinder, while bringing up the rear was Cliff Lane's long spiral. An hour out of Mojave, the flight went into superdrive and left the Solar Combine far behind in a matter of minutes.

By the clock, it was weeks later that the Solar Guard's flight dropped down out of superdrive and took a look around. The Little Man, in Thompson's ship, used his own instruments and indicated that the yellow star—it was more than a star at their distance—dead ahead was the one they sought.

"Downing," called Lane. "How's your power reserve?"

"Like yours, probably."

"We'd better find a close-in, hotter-than-the-hinges planet where they won't be populating and charge up, what say?"

"Good idea. Better than the original plan of charging in flight. If it's close in, it'll have ceased revolution, probably. We can hit the twilight zone and rest our feet a bit."

"O.K. I'll put the searchers on it."

"We'd better take it by relays, though. A fleet that's planeted for charging isn't in the most admirable position for attack."

"Reasonable. You charge, Thompson'll guard, and I'll scout around."

"You'll do nothing of the sort," growled Downing. "You and Thompson will both guard."

"Afraid?"

"No, you idiot. I'm jealous as hell. I don't want you to take all the glory."

"And that's probably the truth," laughed Lane.

"Take it or leave it."

Thompson interrupted. "This sounds like the leading edge of a fight. Stop it. We'll play it safe—Downing's way."

"O.K.," assented Lane cheerfully enough.

"Thing that bothers me," muttered Downing, "is the fact that if this bunch have any stuff, we're being recorded on the tapes right now."

"So?"

"And if they're as nasty as the Little Man claims, they'll be here with all of their nastiness."

"All right," snapped Lane. "We've got detectors and analyzers, haven't we?"

"Uh-huh. But we're a long way from home base. What we've got we've got to keep—and use. They can toss the book at us and go home for another library. Follow?"

"Yup. Located a planet yet?"

"Haven't you been paying attention?"

"No. You're in the lead. I'm merely following as best I can."

"Then sharp up. We're heading for the innermost planet now."

"Go ahead—we'll go in to see. Then Lane and I will scout the sky above to keep off the incoming bunch, if any," said Thompson.

It was an armed watch. Downing's flight landed and set up the solar collectors. From the ships there came a group of planet-mounted modines which had little to offer over the turrets in the ships save adding to their numbers.

The other two flights dropped off their planet-mounts, too, since they were of no use a-flight and might even become a detriment if trouble demanded swift maneuver.

Then a regular patrol schedule was set up and alternately Lane and Thompson took to the sky to cover the area. The detectors were overhauled and stepped up to the theoretical limit of their efficiency, and couplers and fire-control systems were hooked in and calibrated.

It took nine days by the clock to get the camp set up, and Downing's flight was almost recharged by the end of that time.

As Thompson's flight went in for re-charge, Downing and Lane discussed the camp.

"I say leave it here," said Lane. "Might be handy."

"When?"

"I don't have any real idea. But we've got one hundred and fifty extra dymodines planet-mounted down there. I say leave it there until we get this problem off our chest."

"Expect trouble?" scoffed Downing.

Lane nodded. "I expect this to end in a running fight with one of the two of us making a blind but accurate stab in the dark and getting that machine the Little Man talks about. If the going gets tough, we can hole out here for some time with the solar collectors running the planet mounts."

"Wonder why the cat race hasn't come up," mused Downing. "It isn't sensible to permit any alien to establish a planethead in your system."

"They might not even know."

"Unlikely."

"Look, though," offered Lane, "we came in sunward, almost scorching our tails. The solar centroid of interference might make any flight detection undistinguishable from background noise."

"Yeah? Remember that we came in over the edge of the sun from somewhere. We were out in space mostly."

"Then you answer it—you asked it!"

The catmen came as Thompson's flight left the camp and Lane's ships dropped into the charging positions. They came in a horde, they came and they swarmed over the two flights that were patrolling.

In a wide circle, the Solarians raced just outside of the camp. The planet mounts covered the sky above, and a veritable arched roof of death-dealing energy covered the twenty-five ships of Lane's flight. The space between the Solar circle and the catman circle was ablaze with energy, and the ether was filled with interference. Even the subether carried its share of crackle, and the orders went on the tone-modulated code instead of voice.

Solid ordnance dropped, and exploded through the crisscrossing of the planet mounts, and the planeted ships ran their charges down instead of up by adding to the fury over their heads. They were sitting ducks and they knew it.

But unlike the sitting duck, these could shoot back. And they took their toll.

Then without apparent reason, the flight of catmen left their whirling circle on a tangent and streaked for space.

Behind them lay nine smoking ships—prey to the Solar Guard.

But they had not gone in vain. There were seven of the Solar Guard that would fly no more—seven ships and a total of one hundred and seventy-five men.

"Whew. They haven't any sense at all," snarled Downing.

"Either that or they value their lives rather poorly."

"Must be. I wouldn't know. But usually a vicious mind doesn't value life too highly."

"I wouldn't be too certain of that."

"All right. I won't belabor the point. I don't know. It just seems—"

The next ten days was under rigid rule. Lane's ships charged, and the last day was spent in replenishing the charges lost in the short but torrid fight.

"Now," said Lane, "what's with this hell-machine that the Little Man mentions?"

"The detectors do not detect," objected Downing.

They confronted the Little Man with the nonoperating detector. He shook his tiny head and worried visibly. He puzzled over it, juggled the circuit controls, and then threw up his hands in bafflement. He spoke to Hotang Lu:

"The field must be so great that the detector is paralyzed."

"It is more than likely. Remember, it was working on Tlembo. It was working on ... on ... I have not the word for their star. Many many light-years away it is good. Close by—it must be paralyzed."

"Then we must make it less sensitive."

"Do you know how?"

"I did once, long ago. But I have forgotten my techniques and my ability lags because of lack of practice."

"And I devoted myself to the arts instead of technology. A revered master at the problem of mental culture; I cannot invade this gadget with tools."

Hotang Lu smiled. "You might try psychoanalyzing it."

"Yes, if it contained but one memory-pattern," laughed Toralen Ki.

"They'd have done better to have sent a plumber and an electrician than we two failures."

"At this point, we must attempt to convey the idea of a search for the master machine."

"It will not be hard. This race will search rather than return home with an incomplete mission. The rivalry that exists between the leaders insures the success of our plan despite any set-back."

Toralen Ki and Hotang Lu faced Lane and Downing. All four shook their heads in complete misunderstanding. Then Hotang Lu sketched a crude diagram of the catmen's star-system. He indicated the master machine and also indicated their search for it and its ultimate destruction.

Lane gritted his teeth. "How big?" he asked aloud, and pointed from the machine to several bits of equipment in the ship.

Toralen Ki said: "Don't know."

Hotang Lu nodded in agreement and tried to convey their ignorance of the size.

"I gather that they've never seen it."

"Chances are if they'd seen it they'd have bopped it themselves," observed Downing.

"Reasonable attitude."

"Well, we have about ten to the twenty-seventh power square miles of blank and utter nothing to curry-comb for a dingus of some sort."

"Blank and utter nothing—hell! I wouldn't mind blank and utter nothing. We could comb it if it weren't for sun, planets, asteroids, meteors, noise-impulses from nowhere-in-particular, just plain hell, and a crew of wild-personalized catmen." Lane paused to take a deep breath. "As it is, the latter is the most complicated of the bunch mentioned. We can't spread out in a space-lattice and comb. We've got to do one of two things. Either we enlist the help—or get freedom of search—of or from the catmen or we comb in a large and armed body."

"That's a nice problem. Either way."

"As has been mentioned before—'Take it or leave it!'"

"Mind explaining how you go about getting chummy with a race that took a swing without asking questions first?"

"That's partly our fault. We just invaded."

"We couldn't spend a few months getting chummy first. We needed power—and bad."

"All right," agreed Lane. "But they didn't know that. And it's all right with me because I'm leery of letting anyone know that I'm vulnerable. Especially people I don't know and therefore cannot trust."

"Have we got what it takes to barge in there and settle down? Can we hold them off until we can make it clear that we don't want their stinking planet?"

"Have we?"

"If we do right now, there'll be a lot of us that stay there for good."

"How many of us are expendable?"

"All of us as long as that dingbat is destroyed."

Lane grimaced. "And how important is it?"

Downing gave an "I don't know" wave of his hands. "We might go looking for trouble, Lane."

"Meaning catch us a single shipload of catmen and let 'em go, well filled with cream and a fine explanation?"

"Might even get a rat or two for them."

"Meaning?"

Downing grinned maliciously. "Guilty conscience?" he taunted. "Forget it, hothead."

"Don't make cracks, Iceberg. O.K., forget it. It's probably the best idea yet. How do we bait a cat trap?"

"Cream—or catnip."

"Very funny," interrupted Thompson. "Exceedingly amusing. You make me laugh, haha," he added in a flat, disgusted tone.

"Shut up," chorused Lane and Downing.

"All right. Then stop making light of this. Bait a cat trap. You'll just have to pirate the planet lanes and catch you one."

"The trouble with you, Thompson, is that you have no sense of humor."

Thompson subsided. He realized that this light banter was a cover-up for a deeper feeling. Deprive them of niggling at one another in a light way and they might take to it in a more serious vein.

"It is agreed, then, that we grab us a boatload of catmen and indoctrinate them with Solarian good will and propaganda."

"It is," said Downing. "Time's a-wasting. Let's grab."

V.

Like a contracting funnel, the Solar Guard closed down on the catman ship. They crowded the catman spacer, forced him into a pocket, and then started to drive him their way.

But unlike a pocketed ship, the catman slashed back. An invisible beam came from somewhere on the craft. It slashed out, closed down upon a midsection of the nearest Solar Guard, and ripped the belly out of the ship. It was both brutal and sickening. One moment the Solarian craft was forcing the catman ship to give space or collide. The next moment the midsection had been gouged away; ripped out as with a vicious claw or a set of cruel, gigantic teeth. The crushed midsection was flung free of the stricken craft and as the ship collapsed over its open belly, and died, the catman slashed at another and another of the Solarians.

"Superdrive!" exploded Lane.

The slashing catman got one more ship before the Solar Guard went into the superdrive and raced away.

"Did you record that?" asked Lane.

"Tried to. The recorder blew."

"So did all of them. Creepers! What a nasty thing to have around."

Thompson said: "One of my techs is repairing a recorder now. He thinks he can give the wave analysis."

"How?"

"He finds that certain of the crystalline structures in the wave recorder are de-crystallized."

"Meaning what?" demanded Lane.

"Meaning that certain frequencies hit the nuclear resonance of the crystalline structures. I'll let you know."

"Let us know quick," said Downing. "If we can analyze it, we can either reproduce it or shield against it."

"Cats at seven o'clock, forty degrees!" exploded the observer in Lane's ship.

"Anywhere else?" demanded Lane.

No answer.

"Fight 'em," snapped Lane.

There were six catmen converging on Lane's command. The rest of the Solar crew flung around and headed for the local fight. Lane's dymodines flashed out and were stopped cold by barriers.

"Crash stations!" ordered Lane. "Prepare for total destruction!"

The six catmen got above Lane's ship and drove him downward with pressors and an occasional light—it must have been very light—touch of the belly-tearing beam. Above the six were the sixty-odd Solarians fighting to get through and fighting a useless battle.

"We can't damage 'em," snarled Lane. "Superdrive—right through 'em!"

He almost made it. His ship rammed up under the stellar drive, came level with the screen of catmen, and almost made it through. But four of them reached forth with the belly-tearing beams and took separate parts of his ship. The warning creak of plates caused the pilot to stop.

Lane's ship was thrust down below again.

"Superdrive—away!"

Lane's ship turned and dropped.

The action was too fast for the Solarian crew, and he left them far behind. But the catmen were right with him all the way.

"Cut it," said Lane in a tired voice. "Let 'em play. Save our strength for later when we can do something."

They went inert. No drive, no sign of fight, no objection.

A side-force hit them, slapping the ship sidewise about fifty feet. It jarred the ship's delicate mechanisms into a short fluster of unreal alarms and ringing signals, but the sturdy stuff was not permanently damaged.

Still no response from Cliff's ship.

They poked him down brutally with a pressor and then jerked him back up again.

More alarms and more nosebleed among the crew.

They caught the ship in force-zones and played catch with it from one catman to the other, poking and thrusting. They ripped off one of the turrets with the snatcher.

Then they stopped. And they waited. Quietly they hung above Lane's ship, watching, watching, watching.

A full, solid, nerve-breaking hour they waited, and the men in Lane's ship waited, wondering.

"Try it!" snapped Lane.

The ship leaped into motion, driving to one side.

Snatchers raced out and caught the fleeing ship, dragged it back, and again they went through the pushing, pulling, tossing program. And then again they stopped with a few, final perfunctory pokes and shoves.

"They're catmen, all right," snarled Lane.

The rest of the Solar Guard came up, and once more they tried to break through the screen to free Lane's ship. Lane shook his head. "Pilot. How long under superdrive before we hit the speed of light?"

"Seven minutes."

"Then drive straight down. I don't think any beam can exceed the speed of light. Once we get up there, they can't reach forward after us, at least."

Lane's ship dropped. And the catmen followed, maintaining their distance with superior balance and accuracy. A minute passed. Two. Three. Four. Five. And then at an even six, a snatcher reached forward and took Lane's ship by the empennage and shook it enough to rend a few seams.

"O.K., cut it," he said wearily. "I wonder what they want of us beside to play cat-and-mouse?"

There were three more sessions of the cat-and-mouse trick, separated by hour intervals. Then the six catmen, their nature satisfied, took hold of Lane's ship in a cluster of snatcher beams. Lane heard the plates give as the fields-of-focus closed down.

He closed his eyes, breathed a short prayer, and waited.

Stellor Downing called Thompson. "Back to One," he said.

"Giving up?"

"Can you think of anything to do?"

"No."

"Well, let's get back where we can plan."

Thompson assented. It was reluctant, however, and a day later, when they landed on One at their camp, he faced Downing. "Sort of solves your problem, doesn't it?"

"Look," snapped Stellor Downing. "I've got a few feelings and a number of nerves. Lane and I were not deeply in love with one another. Yes, it solves a lot of problems, Thompson, but don't taunt me about it, or I'll take a modine to your throat, see?"

"We might have tried again," insisted Thompson.

"We might have tried for a month. We couldn't even touch them. If you're intimating that I gave up quick—?"

"You weren't leaning over backwards."

"Quoting an old, famous fable, 'sometimes it is better to fall flat on your face.'"

"Meaning?"

"We've got whole skins. They were after captives, not meat. They wanted the same thing we do but they got 'em first."

"So?"

"So we take whatever wave analysis we have and try to figure 'em out. If we can reproduce any of that stuff, we'll go back."

"Hm-m-m."

"Look, Thompson, as far as this job is concerned, your job of keeping Lane and myself out of one another's hair is over. One head of hair is gone, see."

"And what do you intend to do about it?"

"I intend to carry on. Now forget about the fact that a personal grudge of mine has been taken out of my hands and let's get on to working out some means of fighting back. Lane is gone. I'm trying not to gloat. But you're not helping. So stop it."

Toralen Ki shook his head in a worried manner. "One is gone."

"A substitute?"

"I fear that any substitute may not be as good."

"Nonsense, Toralen. Were there a better man than either, we'd have selected him; if either had not existed, a lesser man would have sufficed."

"The right kind is so very few," complained Toralen Ki.

"We can find one. We will have to return to their planet to do so, and it will be harder for us—but it can be done. No good general has only one plan of battle."

"But so much depends—Ah well, despair is the product of the inferior intellect. We will, we must carry on."

Hotang Lu opened his large case. "I will contact our superiors immediately and ask their advice."

"Yes," nodded Toralen Ki. "Also ask them if they have the answer to the less-sensitive detector, yet."

Hotang turned the communicator on and waited for it to warm up. His hand dropped into the case and came up with another small instrument of extreme complexity.

"Once the suppressor is destroyed," he said with a smile of contemplation, "we can use this on them."

"And that means success!" breathed Toralen Ki. "From that time on, our plans—"

"Wait, the communicator is operating," said Hotang Lu, waving a hand. He reached for the communicator's controls and started to talk swiftly, pressing his head against the plate above the voice-transmitter.

Flight Commander Thompson handed Downing a sheaf of papers. "There's the wave analysis," he said with pride.

Downing looked them over. "You've got the technical crew. Can we reproduce all or any of it?"

"Only by tearing down a couple of modine directors. The boys can convert the spotting, training, and ranging circuits—they'll use the components—and rebuild the thing to generate barriers. The snatcher is easy. We'll just juggle the main modulating system of a tractor generator. That comes out so simple I feel slightly sick at not having thought of it myself."

"What is its analysis?" asked Downing.

"Couple a force beam with a tractor focus-zone generator. The tractor, you know, operates on the field-of-focus principle. A rough sphere at the end of the beam—anything in that field is drawn. The snatcher merely applies the field-of-focus idea to the side-thrust of a force beam. You raise the power several times and anchor it with a superdrive tube coupled so that the thrust is balanced against a spatial thrust instead of the ship. That tears the guts out of anything."

"I have an idea that you might be able to cut instead of tear if you include some nuclear-resonant frequencies in the field of focus generator."

"Is it necessary?"

"Might be interesting," said Downing. "They tear. If we land on them with something that quickly, precisely, quietly, and almost painlessly slices a sphere out of one of their ships, they may be impressed."

"You have something there. I'm going to tear into some of the planet-mounted jobs. We are now sixty-three ships. I can make one snatcher out of every dymodine that's planet-mounted out here. Shall I?"

"How long?"

"Ten hours each."

"Six hundred and thirty hours. Twenty-six days and six hours."

"We'll make it in twenty days. By the time the boys get to Number Ten or Twelve they'll be working shortcut and on production-line basis and the piece-time will drop."

"Twenty days is long enough, believe me. We'll toss in my gang and Lane's gang, too. They can go to work on the modine directors and make barriers out of 'em if you claim they'll work."

"They'll work."

"Then let's get going. The Little Guys are tearing their hair as it is."

Thompson nodded.

"But look," said Downing, "don't rip up any dymodines ahead. Convert slowly. If the catmen attack, we'll need all we can muster to fight 'em off."

"Right."

"And as for Cliff Lane—he isn't dead until we prove it, see? So far as I know, he might be getting an education in cat-culture right now."

Thompson looked at Downing for a long time, saying nothing. Then he turned and left, still without comment.

Cliff Lane and his ship were herded down to the ground. His ship was surrounded by the six catmen, their beams pointed at him, waiting. For an hour they waited, using all the patience of the feline. It got on the nerves of the humans, and they wanted to do something.

Their trouble was that they didn't quite know what to do.