Nomad

George O. Smith

Nomad

By WESLEY LONG

Illustrated by Orban

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Astounding Science-Fiction, December 1944, January, February 1945.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

I.

Guy Maynard left the Bureau of Exploration Building at Sahara Base and walked right into trouble. It came more or less of a surprise; not the trouble as a condition but the manner and place of its coming was the shocking quality. Guy Maynard was used to trouble but like all men who hold commissions in the Terran Space Patrol, he was used to trouble in the proper places and in the proper doses.

But to find trouble in the middle of Sahara Base was definitely stunning. Sahara Base was as restricted an area as had ever been guarded and yet trouble had come for Guy.

The trouble was a MacMillan held in the clawlike hand of a Martian. The bad business end was dead-center for the pit of Guy's stomach and the steadiness of the weapon's aim indicated that the Martian who held the opposite end of the ugly weapon knew his MacMillans.

Maynard's stomach crawled, not because of the aim on said midriff, but at the idea of a MacMillan being aimed at any portion of the anatomy. His mind raced through several possibilities as he recalled previous mental theories on what he would do if and when such a thing happened.

In his mind's eye, Guy Maynard had met MacMillan-holding Martians before and in that mental playlet, Guy had gone into swift action using his physical prowess to best the weapon-holding enemy. In all of his thoughts, Guy had succeeded in erasing the menace though at one time it ended in death to the enemy and at other times Guy had used the enemy's own weapon to march him swiftly to the Intelligence Bureau for questioning. The latter always resulted in the uncovering of some malignant plot for which Maynard received plaudits, decorations, and an increase in rank.

Now Guy Maynard was no youngster. He was twenty-four, and well educated. He had seen action before this and had come through the Martio-Terran incident unscathed. Openly he admitted that he had been lucky during those weeks of trouble but in his own mind, Maynard secretly believed that it was his ability and his brain that brought him through without a scratch.

His dreaming of action above and beyond the call of duty was normal for any young man of intelligence and imagination.

But as his mind raced on and on, it also came to the conclusion that the law of survival was higher than the desire to die for a theory.

Therefore it was with inward sickness that Guy Maynard stopped short on the sidewalk before the Bureau of Exploration Building and did nothing. He did not look around because the fact that this Martian was able to stand before him in Sahara Base with a MacMillan pointed at his stomach was evidence enough that they were alone on the street. Had anyone seen them, the Martian would have been literally torn to bits by the semi-permanent MacMillan mounts that lined the roof tops.

The Martian had everything his own way, and so Maynard waited. It was the Martian's move.

"Guy Maynard?"

Maynard did not feel that such an unnecessary question required an answer. The Martian would not have been menacing him if he hadn't known whom he wanted.

"Guy Maynard, I advise that you do nothing," said the Martian. His voice was flat and metallic like all Martian voices, and the sharply-chiseled features were expressionless as are all Martian faces. "You are to come with me," finished the Martian needlessly. He had not concluded the last bit of information when invisible tractor beams lashed down and caught the pair in their field of focus and lifted them straight up.

The velocity was terrific, and the only thing that saved them suffocation in the extreme upper stratosphere was the entrapped air that went along with the field of focus.

The sky went dark and the stars winked in the same sky as the flaming sun.

And then they entered the space lock of an almost invisible spaceship. The door slammed behind them and air rushed into the confines of the lock just as the tractors were snuffed.

Maynard arose from the floor to face once more that rigidly held MacMillan. Before he could move, the door behind him flashed open and three Martians swarmed in upon him and trussed him with straps. They carried him to a small room and strapped him to a surgeon's table.

The one with the MacMillan holstered the weapon as the ship started off at 3-G.

"Now, Guy Maynard, we may talk."

Maynard glared.

"It is regrettable that this should be necessary," apologized the Martian. "I am Kregon. Your being restrained is but a physical necessity; I happen to know that you are the match for any two of us. Therefore we have strapped you down until we have had a chance to speak our mind. After which you may be freed—depending upon your reception of the proposition we have to offer."

Maynard merely waited. It was very unsatisfactory, this glaring, for the Martian went on as though Maynard were beaming in glee and anxiously awaiting for the "Proposition." He recalled training which indicated that the first thing to do when confronted by captors is to remain silent at all cost. To merely admit that your name was correctly expressed by the captor was to break the ice. Once the verbal ice was broken, the more leading information was easier to extract; a dead and stony silence was hard to break.

"Guy Maynard, we would like to know where the Orionad is," said Kregon. "We have here fifty thousand reasons why you should tell. Fifty thousand, silver-backed reasons, legal for trade in any part of the inhabited Solar System and possibly some not-inhabited places."

No answer.

"You know where the Orionad is," went on Kregon. "You are the aide to Space Marshal Greggor of the Bureau of Exploration who sent the Orionad off on her present mission. The orders were secret, that we know. We want to know those orders."

No answer.

"We of Mars feel that the Orionad may be operating against the best interests of Mars. Your continued silence is enhancing that belief. Could it be that we have captured the first prisoner in a new Terra-Martian fracas? Or if the Orionad is not operating against Mars, I can see no reason for continued silence on your part."

No answer, though Maynard knew that the Orionad was not menacing anything Martian. He realized the trap they were laying for him and since he could not avoid it, he walked into it.

Kregon paused. Then he started off on a new track. "You are probably immunized against iso-dinilamine. Most officials are, and their aides are also, especially the aide to such an important official as Space Marshal Greggor. That is too bad, Guy Maynard. Terra is still behind the times. Haven't they heard that the immunization given by anti-lamine is good except when anti-lamine is decomposed by a low voltage, low frequency electric current? They must know that," said Kregon with as close to a smile as any Martian could get. It was also cynically inclined. "After all, it was Dr. Frederich of the Terran Medical Corps who discovered it."

Maynard knew what was coming and he wanted desperately to squirm and wriggle enough to scratch his spine. The little beads of sweat that had come along his backbone at Kregon's cool explanation were beginning to itch. But he controlled the impulse.

"We are not given to torture," explained the Martian. "Otherwise we could devise something definitely tongue-loosening. For instance, we could have you observe some surgical experiments on—say—Laura Greggor."

The beads of sweat broke out over Maynard's face. It was a harsh thought and very close to home. And yet there was a separate section of his mind that told him that Laura would undergo that treatment without talking and that he would have to suffer mentally while he watched, because she would hold nothing but contempt for a man who would talk to save her from what she would go through herself. He wondered whether they had Laura Greggor already and were going to do as they said. That was a hard thing to reason out. He feared that he would speak freely to save Laura disfigurement and torture; knowing as he spoke that Laura would forever afterward hate him for being a weakling. Did they have her—?

"Unfortunately for us, we have not had the opportunity of getting the daughter of the Space Marshal. But there are other things. They are far superior, too. I was against the torture method just described because I know that Mars would never have peace again if we destroyed the daughter of Space Marshal Greggor. Your disappearance will be explained by evidence. A wrecked spaceship or flier, will take care of the question of Guy Maynard, whereas Laura Greggor is forbidden to travel in military vehicles."

Kregon turned and called through the open door. His confederates came with a portable cart upon which was an equipment case, complete with plug-in cords, electrodes, and controls.

"You will find that low frequency, low voltage electricity is very excruciating. It will not kill nor maim nor impair. But it will offer you an insight on the torture of the damned. Ultimately, we will have decomposed the anti-lamine in your system and then you will speak freely under the influence of iso-dinilamine. Oh yes, Guy Maynard, we will give you respite. The current will be turned off periodically. Five minutes on and five minutes off. This is in order for you to rest."

"—to rest!" said Maynard's mind. Irony. For the mind would count the seconds during the five free minutes, awaiting with horror the next period of current. And during the five minutes of electrical horror, the mind would be counting the seconds that remain before the period of quiet, knowing that the peaceful period only preceded more torture.

Kregon's helpers tied electrodes to feet, hands, and the back of his head. Then Kregon approached with a syringe and with an apologetic gesture slid the needle into Maynard's arm and discharged the hypodermic.

"Now," he asked, "before we start this painful process, would you care to do this the easy way? After all, Maynard, we are going to have the answer anyway. For your own sake, why not give it without pain. That offer of fifty thousand solars will be withdrawn upon the instant that the switch is closed."

Maynard glared and broke his silence. "And have to go through it anyway? Just so that you will be certain that I'm not lying? No!"

Kregon shook his head. "That possibility hadn't really occurred to us. You aren't that kind of man, Maynard. I think that the best kind of individual is the man who knows when to tell a lie and when not to tell. Too bad that you will never have the opportunity of trying that philosophy, but I think it best for the individual, though often not best for society in general. Accept the apology of a warrior, Guy Maynard, that this is necessary, and try to understand that if the cases were reversed, you would be in my place and I in yours. I salute you and say good-by with regrets."

Maynard strained against the straps in futility. He felt that sense of failure overwhelm him again, and he fought against his fate in spite of the fact that there was nothing he could do about it. Another man would have resigned himself, realizing futility when it presented itself, and possibly would have made some sort of prayer. But Guy Maynard fought—

And the surge of low frequency, low voltage electricity raced into his body, removing everything but the torture of jerking muscle and the pain of twitching nerves. It was terrible torture. He felt that he could count each reversal of the low frequency, and yet he could do nothing of his own free will. The clock upon the wall danced before his jerking eyeballs so that he could not see the hands no matter how hard he tried. Ironically, it was a Martian clock and not calibrated into Terran time; it would have had no bearing on the five-minute periods of sheer hell.

Ben Williamson raced across the sand of Sahara Base, raising a curling cloud of dust behind him. The little command car rocketed and careened as Williamson approached his destroyer, and then the long, curling cloud of dust took on the appearance of a huge exclamation point as the brakes locked and the command car slid to a stop beside the space lock. Williamson leaped from the command car and inside with three long strides.

He caught the auxiliary switch on his way past, and the space lock whirred shut. "Executive to pilot," he yelled. "Take her up at six."

The floor surged, throwing Williamson to his knees. Defiantly, Ben crawled to the executive's chair and rolled into the padded, body-supporting seat. He lay there for some seconds, breathing heavily. Then from the communicator there came the query:

"Pilot to executive: Received. What's doing?"

"Executive to crew: Martian of the Mardinex class snatched Guy Maynard on a tractor. We're to pursue and destroy."

"Golly!" breathed the pilot. "Maynard!"

"That's right," said Williamson. "They grabbed him right in front of the BuEx and that's that."

"But to destroy them—?"

"We're running under TSI orders, you know," reminded Williamson.

"Yeah, I know. But killing off one of our own people doesn't sound good to me. Makes me feel like a murderer."

"I know," said Ben. "But remember, Maynard was grabbed by a Martian. Being an aide to Greggor, he was filled to the eyebrows with anti-lamine. That means the electro-treatment for him, plus a good shot of iso-dinilamine. All we're doing is giving peace to a man who is suffering the tortures of hell. After all, would any of you care to go on living after that combination was finished?"

"No, I guess not. Must be worse than death not to have a mind."

"What's worse is what happens. You haven't a mind—and yet you have enough mind to realize that fact. Strange psychological tangle, but there it is. Tough as it is, we've got to go through with it."

"They're after some information on the Orionad?"

"Probably. That's why we're taking out after them. It's the only reason why Guy Maynard was covered under the TSI order."

"Too bad," said the pilot.

"It is," agreed Williamson. "But—prepare for action. Check all ordnance."

It was almost an hour later that the communicator buzzed again. "Observer to executive: Martian of Mardinex class spotted."

"Certain identification?"

"Only from the cardex file. Can't see her yet, but the spotters have picked up a ship having the characteristics of the Mardinex class. It's the Mardinex herself, Ben, because she's the only one left in that class. Old tub, not much good for anything except a fool's errand like this."

"Turretman to executive: Have we got a chance, tackling a first-line ship like the Mardinex in a destroyer?"

"Only one chance. They probably didn't staff it too well. On an abortive attempt like this, they'd put only those men they could afford to lose aboard. Probably a skeleton crew. Also the knowledge that detection meant extermination, therefore go fast and light and as frugal as possible on crewmen. That's our one chance."

"One more chance," interrupted the technician. "We have the drive pattern of the Mardinex in the cardex. We can bollix their drive. That's one more item in our favor."

"Right," said Ben. "What's our velocity with respect to theirs?"

"Forty miles per second."

"Tim, launch two torpedoes immediately. Pete, continue course above Mardinex and cross their apex at two hundred miles. Tim, as we cross their apex, drop a case of interferers. Once that is done, Pete, drop back and give Tim a chance to say hello with the AutoMacs."

"Giving them the whole thing at once?"

"Yes. And one thing more, Jimmy?"

"Technician to executive," answered Jimmy. "I'm here."

"Can you rig your drive-pattern interferer?"

"In about a minute. I've been setting up the constants from the cardex file."

"And hoping they've not been changed?" asked Ben with a smile.

"Right."

The little destroyer lurched imperceptibly as the torpedoes were launched, and then continued on its course a hundred miles to the south of the Martian ship, passing quickly above the Mardinex and across the apex of the Martian's nose. The turretman was busy for several seconds dropping his case of interferers from the discharge lock. The little metal boxes spread out in space and began to emit signals.

Then the destroyer dropped back, and from the turret there came the angry buzz of the AutoMacs. On the driving fin of the Mardinex appeared an incandescent spot that grew quickly and trailed a fine line of luminous gas behind it. Then the turrets of the Mardinex whipped around and Tim shouted: "Look out!"

His shout was not soon enough. On the turret of the Martian ship there appeared two spots of light that were just above the threshold of vision against the black sky. The destroyer bucked dangerously, and the acceleration fell sharply.

"Hulled us."

On the pilot's panel there appeared a number of winking pilot lights. "We'll get along," said he, studying the lights and interpreting their warning.

"Got him!" said the turretman. The top turret of the Mardinex erupted in a flare of white flame blown outward by the air inside of the ship.

"Can we catch him for another shot?" asked Ben pleadingly.

"Not a chance," answered Pete. "We're out of this fight."

"No, we're not," said Ben. "Look!"

Before the Mardinex there began to erupt a myriad of tiny, winking spots. The meteor spotting equipment and projectile intercepting equipment were flashing the interferers one after the other with huge bolts from the secondary battery of the Mardinex.

Ben counted the flashes and then asked the technician: "How many spotters has the Mardinex?"

"Thirty."

"Good. The torps have a chance then." The nonradiating torpedoes would be ignored by the spotting equipment since the emission of the interferers made them appear gigantic and dangerously close to the nonthinking equipment. The torpedoes, on the other hand, would be approaching the Mardinex from below and slowly enough to be considered not dangerous to the integrating equipment. If they arrived before the spotting circuits destroyed the entire case of interferers—

The lower dome of the Mardinex suddenly sported a jagged hole. And almost immediately there was a flash of explosive inside of the lower portion of the Martian ship. The lower observation dome split like a cracked egg, and the glass shattered and flew out. Portholes blew out in long streamers of fire around the lower third of the Mardinex and a series of shattering cracks started up the flank of the ship.

"There goes number two—a clean miss," swore Ben.

"Number one did a fine job."

"I know but—"

"This'll polish 'em off," came Jimmy's voice. "Here goes the drive scrambler."

"Hey! No—!" started Ben, but the whining of the generators and the dimming of the lights told him he was too late.

The Mardinex staggered and then leaped forward until six full gravities. Bits of broken hull and fractured insides trailed out behind the Mardinex as the derelict's added acceleration tore them loose. Within seconds, the stricken Martian warship was out of the sight of the Terrans.

"No reprimand, Jimmy," said Ben Williamson soberly. "I did hope to recover Guy's body."

II.

Thomakein, the Ertinian, stopped the recorder as the Terran ship reversed itself painfully and began to decelerate for the trip back to home. He nodded to himself and made a verbal addition to the recording, stating that the smaller ship had been satisfied as to the destruction of the larger, otherwise a continuance of the fight would have been inevitable. Then Thomakein placed the recording in a can and placed it on a shelf containing other recordings. He forgot about it then, for there was something more interesting in view.

That derelict warship would be a veritable mine of information about the culture of this system. All warships are gold mines of information concerning the technical abilities, the culture, the beliefs, and the people themselves.

Could he assume the destruction of the crew in the derelict?

The smaller ship had—unless they were out of the battle and forced to withdraw due to lack of fighting contact. That didn't seem right to Thomakein. For the smaller ship to attack the larger ship meant a dogged determination. There would have been a last-try stand on the part of the smaller ship no matter how much faster the larger ship were. At worst, the determination seemed to indicate that ramming the larger ship was not out of order.

But the smaller ship had not rammed the larger. Hadn't even tried. In fact, the smaller ship had turned and started to decelerate as soon as the larger ship had doubled her speed.

Thomakein couldn't read either of the name plates of the two fighting ships. He had no idea as to the origin of the two. As an Ertinian, Thomakein couldn't even recognize the characters let alone read them. He was forced to go once more on deduction.

The course of the larger vessel. It was obviously fleeing from the smaller ship. Thomakein played with his computer for a bit and came to two possibilities, one of which was remote, the other pointing to the fourth planet.

A carefully collected table of masses and other physical constants of the planets of Sol was consulted.

Thomakein retrieved his recording, set it up and added:

"The smaller ship, noticing the increased acceleration of the larger, assumed—probably—that the larger ship's crew was killed by the increased gravity-apparent. Since the larger ship was fleeing, it would in all probability have used every bit of acceleration that the crew could stand. Its course was dead-center for the fourth planet's position if integrated for a course based on the larger ship's velocity and direction and acceleration at and prior to the engagement.

"This fourth planet has a surface gravity of approximately one-eighth of the acceleration of the larger ship. Doubling this means that the crew must withstand sixteen gravities. The chances of any being of intelligent size withstanding sixteen gravities is of course depending upon an infinite number of factors. However, the probable reasoning of the smaller ship is that sixteen gravities will kill the crew of the larger ship. Otherwise they would have continued to try to do battle with the larger ship. Their return indicates that they were satisfied."

Thomakein nodded again, replaced the recording, and then paced the derelict Mardinex for a full hour with every constant at his disposal on the recorders.

At the end of that hour, Thomakein noted that nothing had registered and he smiled with assurance.

He stretched and said to himself: "I can stand under four gravities. I can live under twelve with the standard Ertinian acceleration garb. But sixteen gravities for one hour? Never."

Thomakein noted the acceleration of the derelict as being slightly over six gravities on his own accelerometer, which registered the Ertinian constant.

Then he began to maneuver his little ship toward the derelict.

Entering the Mardinex through the blasted observation dome was no great problem. The lower meteor spotters and most of the machinery had gone with the dome and so no pressor came forth to keep Thomakein from his intention.

The insides were a mess. Broken girders and ruined equipment made a bad tangle of the lower third of the great warship. Thomakein jockeyed the little ship back and forth inside of the derelict until he had lodged it against the remainder of a lower deck in such a manner as to keep it there under the six Terran gravities of acceleration. Then he donned spacesuit and started to prowl the ship. It was painful and heavy going, but Thomakein made it slowly.

An hour later, Thomakein heard the ringing of alarms, coming from somewhere up above, and the sound made him stop suddenly. Sound, he reasoned, requires air for propagation. The sound came through the floor, but somewhere there must be air inside of the derelict.

So upward he went through the damage. He found an air-tight door and fought the catch until it puffed open, nearly throwing him back into the damaged opening. White-faced, Thomakein held on until his breath returned, and then with a determined look at the gap below—and the place where he would have been if he had fallen out of the derelict—Thomakein tried the door again. He closed the outer door and tried the inner.

His alien grasp of mechanics was not universal enough to discover his trouble immediately. But it was logical, and logic told him to look for the air vent. He found it, and turned the valve permitting air to enter the air-tight door system. The inner door opened easily and Thomakein entered a portion of the hull where the alarm bells rang loud and clear.

He found them ringing in a room filled with control instruments. Throwing the dome of his suit back over his head, Thomakein looked around him with interest. There was nothing in the room that logic or a grasp of elementary mechanics could solve. It did Thomakein no good to look at the Martian characters that labeled the instruments and dials, for he recognized nothing of any part of the Solar System.

He did recognize the bloody lump of inert flesh as having once been the operator of this room—or one of them he came to conclude as his search found others.

Thomakein was not squeamish. But they did litter up the place and the pools of blood made the floor slippery which was dangerous under 6-G Terran—or for Thomakein, five point six eight. So Thomakein struggled with the Martian bodies and hauled them to the corridor where he let them drop over the edge of the central well onto the bulkhead below. He returned to the instrument room in an attempt to find out what the bell-ringing could mean.

He inspected the celestial globe with some interest until he noticed that the upper limb contained some minute, luminous spheres—prolate spheroids to be exact. Wondering, Thomakein tried to look forward and up with respect to the ship's course.

His anxiety increased. He was about to meet a whole battle fleet that was spread out in a dragnet pattern. Then before he could worry about it he was through the network and some of the ships tried to follow but with no success. The Mardinex bucked and pitched as tractors were applied and subsequently broken as the tension reached overload values.

Thomakein smiled. Their inability to catch him plus their obvious willingness to let the matter drop with but a perfunctory try gave him sufficient evidence as to their origin.

They could never catch a ship under six gravities when the best they could do was three. The functions with respect to one another would be as though the faster ship were accelerating away from the slower ship by 3-G plus the initial velocity of the faster ship's intrinsic speed, for the pursuers were standing still.

The Mardinex swept out past Mars and Thomakein smiled more and more. This maze of equipment was better than anything that he had expected. The Ertinians would really get the information as to the kind of people who inhabited this system.

Thomakein wandered idly from room to room, finding dead Martians and dropping them onto the bulkhead. Two he saved for the surgeons of Ertene to inspect; they were in fair physical condition compared to the rest but they were no less dead from acceleration pressure.

Eventually, Thomakein came to the room wherein Guy Maynard was lying strapped to the surgeon's table. The Ertinian opened the door and walked idly in, looking the room over quickly to see which item of interest was the most compelling.

His glance fell upon Maynard and passed onward to the equipment on the cart beyond the Terran. Then Thomakein's eyes snapped back to the unconscious Terran and Thomakein's jaw fell while his face took on an astonished look.

Thomakein often remarked afterwards that it was a shame that no one of his photographically inclined friends had been present. He'd have enjoyed a picture of himself at that moment and he realized the fact.

Thomakein had ignored the dead Martians. They were different enough to permit him a certain amount of callousness.

But the man strapped to the table, and hooked up to the diabolical looking machine was the image of an Ertinian! Thomakein didn't know what the machine was for, but his logical mind told him that if this man, different from the rest, were strapped to a table with some sort of electronic equipment tied to his hands, feet, and head, it was sufficient evidence that this was a captive and the machine some sort of torture. He stepped forward and jerked the electrodes from Maynard's inert frame and pushed the machine backward onto the floor with a foot.

A quick check told Thomakein that the unknown man was not dead, though nearly so.

He raced through the derelict to his own ship and returned with a stimulant. The man remained unconscious but alive. His eyes opened after a long time, but behind them was no sign of intelligence. They merely stared foolishly, and closed for long periods.

Thomakein tended the man as best he could with the limited supplies from his own ship and then began to plan his return to Ertene with his find.

Days passed, and Thomakein unwillingly abandoned any hope of having this man give him any information. The man was as one dead. He could not speak, nor could he understand anything. Thomakein decided that the best thing to do was to take the unknown man to Ertene with him. Perhaps Charalas, or one of his contemporary neuro-surgeons could bring this man to himself. Thomakein diagnosed the illness as some sort of nerve shock though he knew that he was no man of medicine.

Yet the surgeons of Ertene were brilliant, and if they could bring this unknown man to himself, they would have a gold mine indeed.

So at the proper time, Thomakein took off from the derelict with the mindless Guy Maynard. By now, the derelict was far beyond the last outpost of the Solar System and obviously beyond detection. Thomakein installed a repeater-circuit detector in the wrecked ship; it would enable him to find the Mardinex at some later time.

So unknowing, Guy Maynard came to Ertene.

The first thing that reached across the mental gap to Guy Maynard was music. Faint, elfin music that seemed to sway and soothe the ragged edges of his mind. It came and it went depending on how he felt.

But gradually the music increased in strength and power, and the lapses were shorter. Warm pleasant light assailed him now and gave him a feeling of bodily well-being. Flashes of clear thinking found him considering the satisfied condition of his body, and the fear and nerve-racking torture of the Martian method of extracting information dropped deeper and deeper into the region of forgetfulness.

Then he realized, one day, that he was being fed. It made him ashamed to be fed at his age, but the thought was fleeting and gone before he could clutch at it and consider why he should be ashamed. One portion of his mind cursed the fleetingness of such thoughts and recognized the possibilities that might lie in the sheer contemplation of self.

There were periods in which someone spoke to him in a strange tongue. It was a throaty voice; a woman. Maynard's inquisitive section tried the problem of what was a woman and why it should stir the rest of him and came to the meager conclusion that it was standard for this body to be stirred by woman: especially women with throaty voices. The tongue was alien; he could understand none of it. But the tones were soothing and pleasant, and they seemed to imply that he should try to understand their meaning.

And then the wonder of meaning came before that alert part of Maynard's mind. What is meaning? it asked. Must things have meaning? It decided that meaning must have some place in the body's existence. It reasoned thus: There is light. Then what is the meaning of light? Must light have a meaning? It must have some importance. Then if light has importance and meaning, so must all things!

Even self!

So the voices strived to teach Ertinian to the Terran while he was still in the mindless state, and gradually he came to think in terms of this alien tongue. But he had been taught to think in Terran, and the Terran words came to mind slowly but surely.

And then came the day when Guy Maynard realized that he was Guy Maynard, and that he had been saved, somehow, from the terrors of the Martian inquisition. He saw the alien tongue for what it was and wondered about it.

Where was he?

Why?

The days wore on with Maynard growing stronger mentally. They gave him everything they could, these Ertinians. Scrolls were given to him to read, and the movement of reflections from his eyeballs motivated recording equipment that spoke the word he was scanning into his ear in that pleasant throaty voice. It was lightning-fast training, but it worked, once Guy's mentality went to work as an entity. Maynard learned to read Ertinian printing and lastly the simplified cursory writing.

Then with handwriting at the gate of learning, they placed his hand around a controlled pencil, and the voice spoke as the controlled pencil wrote. They spoke Ertinian to him, not knowing Terran, though his earlier replies were recorded.

And as he strengthened, his replies made sense, and for every Ertinian word impressed upon his mind, he gave them the Terran word. They taught him composition and grammar as he taught them, and whether it was by the written script or the spoken word, the interchange of knowledge was complete.

One day he asked: "Where am I?"

And the doctor replied: "You are on Ertene."

"That I know. But where or what is Ertene?"

"Ertene is a wandering planet. We found you almost dead in a derelict spaceship and brought you back to life."

"I recall parts of that. But—Ertene?"

"Generations ago, Ertene left her parent sun because of a great, impending cataclysm. Since then we have been wandering in space in search of a suitable home."

"Sol is not far away—you will find a home there."

The doctor smiled sagely and did not comment on that. Maynard wondered about it briefly and tried to explain, but they would have none of it.

He tried at later times, but there was a reticence about their accepting Sol as a home sun. No matter what attack he tried, there was a casual reference to a decision to be made in the future.

But their lessons continued, and Guy progressed from the hospital to the spacious grounds. He sought the libraries and read quite a bit, for they urged him to, saying: "We can not entertain you continually. You are not strong enough to work, nor will we permit you to take any position. Therefore your best bet is to continue learning. In fact, Guy, you have a job to perform on Ertene. You are to become well versed in Ertinian lore so that you may converse with us freely and draw comparisons between Ertene and your Terra for us. Therefore apply yourself."

Guy agreed that if he could do nothing else, he could at least do their bidding.

So he applied himself. He read. He spoke at length with those about him. He practised with the writing machine. He accepted their customs with the air of one who feels that he must, in order that he be accepted.

And gradually he took on the manner of an Ertinian. He spoke with a pure Ertinian accent, he thought in Ertinian terms, and his hand was the handwriting of an Ertinian. And from his studies he came to the next question.

"Charalas, how could you tell me from an Ertinian?"

Charalas smiled. "We can."

"But how? It is not apparent."

"Not to you. It is one of those things that you miss because you are too close to it. It is like your adage: 'Cannot see the forest for the trees.' It will come out."

"Come out?"

"Grow out," smiled the neuro-surgeon. "Your ... beard. You notice that I used the Terran name. That is because we have no comparable term in Ertinian. That is because no Ertinian ever grew hair on his face. Daily, you ... shave ... with an edged tool we furnished you upon your request. You were robotlike in those days, Guy. You performed certain duties instinctively and the lack of ... shaving equipment ... caused you no end of mental concern. Thomakein studied your books and had a ... razor ... fashioned for you."

"Whiskers. I never noticed that."

"No, it is one of those things. Save for that, Guy, you could lose yourself among us. The ... mustache ... you wear marks you on Ertene as an alien."

"I could shave that off."

"No. Do not. It is a mark of distinction. Everyone on Ertene has seen your picture with it and therefore you will be accorded the deference we show an alien when people see it. Otherwise you would be expected to behave as we do in all things."

"That I can do."

"We know that. But there is another reason for our request. One day you will know about it. It has to do with our decision concerning alliance with Sol's family."

Guy considered. "Soon?"

"It will be some time."

Again that unwillingness to discuss the future. Guy thought it over and decided that this was something beyond him. He, too, let the matter drop for the present and took a new subject.

"Charalas, this sun of yours. It is not a true sun."

"No," laughed Charalas. "It is not."

"Nor is it anything like a true sun. Matter is stable stuff only under certain limits. If that size were truly solar matter, it would necessarily be so dense that space would be warped in around it so tight that nothing could emerge—radiation, I mean. To the observer, it would not exist. That is axiomatic. If a bit of solar matter of that size were isolated, it would merely expand and cool in a matter of hours—if it were solar-core matter it would probably be curtains for anything that tried to live in the neighborhood. Matter of that size is stable only at reasonable temperatures. I don't know the limits, but I'd guess that three or four thousand degrees kelvin would be tops. Oh, I forgot the opposite end; the very high temperature white dwarf might be that size—but it would warp space as I said before and thus do no good. Therefore a true sun of that size and mass is impossible.

"Another thing, Charalas. We are close to Sol. A light-week or less. That would have been seen ... should have been seen by our observatories. Why haven't they seen it?"

"Our shield," explained Charalas, "explains both. You see, Guy, in order that a planet may wander space, some means of solar effect must be maintained. As you say, nothing practical can be found in nature. Our planet drive is poorly controlled. We can not maneuver Ertene as you would a spaceship. It requires great power to even shift the course of Ertene by so much as a few degrees. We've taken luck as a course through the galaxy and have visited only those stars that have lain along our course. Trying to swing anything of solar mass would be impossible. Ertene would merely leave the sun; the sun would not answer Ertene's gravitational pull.

"But this is trivial. Obviously we have no real sun. But we needed one." Charalas smiled shyly. "At this point I must sound braggart," he said, "but it was an ancestor of mine—Timalas—who brought Ertene her sun."

"Great sounding guy," commented the Terran.

"He was. Ertene left the parent sun with only the light-shield. The light-shield, Guy, is a screen of energy that permits radiation to pass inwardly but not outwardly. Thus we collect the radiation of all the stars and lose but a minute quantity of the input from losses. That kept Ertene warm during those first years of our wandering.

"It also presented Ertene with a serious problem. The entire sky was faintly luminous. It was neither night nor day at any place on Ertene, but a half-light all the time. Disconcerting and entirely alien to the human animal. Evolutionary strains might have appeared to accept this strange condition, but Timalas decided that Intis, the lesser moon, would serve as a sun. He converted the screen slightly, distorting it so that the focal point for incoming radiation was at Intis. The lesser moon became incandescent, eventually, and serves as Ertene's sun. It is synthetic. The other radiations that prove useful to growing things and to man but which are not visible are emitted right from the inner surface of the light-shield itself. Intis serves as the source of light and most of the heat. It is a natural effect, giving us beautiful sunrises and peaceful sunsets. The radiation that causes growth and healthful effects is ever-present, because of the screen. Some heat, too, for that is included in the beneficial radiation. But the visible spectrum is directed at Intis along with a great quantity of the heat rays. Intis is small, Guy, and it is also beneficial that the re-radiation from Intis that misses Ertene and falls on the screen is converted also. Much of Ertene's power is derived from the screen itself—a back-energy collected from the screen generator."

"So the effective sun is the result of an energy shield? And this same shield prevents any radiation from leaving this region. I can see why we haven't seen Ertene. You can't see something that doesn't radiate. But what about occultation?"

"Quite possible. But the size of the screen is such that it is of stellar size as seen from stellar distances. It is but a true point in space." Charalas smiled. "I was about to say a point-source of light similar to a star but the shield is a point-source of no-light, really. Occultation is possible but the probabilities are remote, plus the probability of a repeat, so that the observer would consider the brief occultation of the star anything but an accident to his photographic plate."

"Don't get you on that."

"It's easy, Guy. Take a star-photograph and lay a thin line across it and see how many stars are really covered by this line—which is of the thickness of the stars themselves. Too few for a non-suspecting observer to tie together into a theory. No, we are safe from detection."

"Detection?"

"Yes. Call it that. Suppose we were to pass through a malignant culture. We did, three generations ago and it was only our shield that saved us from being absorbed into that system. We would have been slaves to that civilization."

"I see."

"Do you?"

"Certainly," said Guy. "You intend to have me present the Solar Government to your leaders. Upon my tale will rest your decision. You will decide whether to join us—or to pass undetected."

"I believe you understand," said Charalas. "So study well and be prepared to draw the most discerning comparisons, for the Council will ask the most delicate questions and you should be able to discuss any phase of Ertene's social system and the corresponding Terran system."

Mentally, Guy bade good-by to Sol. He applied himself to his Ertinian lessons because he felt that if Sol were lost to him—as it might be—he could at least enter the Ertinian life as an Ertinian.

III.

Guy Maynard, the Terran, became steeped in Ertinian lore. He went at it with the same intensity that he went at anything else, and possibly driven with the heart-chilling thought that he might not be able to convince Ertene that Sol had a place for her. He saw that possibility, and prayed against it, yet he realized that Ertene was a planet of her own mind and that they might decide against alliance. It was a selling job he had to do.

And if not—

Guy Maynard would have to remain on Ertene. Therefore in either case it would serve him best to become as Ertinian as possible. He did not believe that they would exile him—that would be dangerous. Nor did he believe that death would accompany his failure to convince Ertene of their place around Sol. The obvious course in case of failure would be to permit him the freedom of the planet; to become in effect, an Ertinian.

He'd be under watch, of course. Escape would prove dangerous for their integrity. Imprisonment was not impossible, but he hoped that his failure to convince would not be so sorry as to have them suspect him.

Of course, an opportunity to escape would be taken, unless he gave his word of honor. Yet, he had sworn the oath of an officer in Terra's space fleet, and that oath compelled him to serve Terra in spite of danger, death, or dishonor to self. He must not give his parole—

Guy fought himself over that problem for days and days. It led him in circular thinking, the outlet to which would be evident only when he found out the Ertinian reaction. Too much depended on that trend; there were too many if's standing between him and any plan for the future.

He forgot his mental whirl in study. He investigated Ertinian science and tucked a number of items away in his memory. He visited the observatory and after a number of visits he plotted Ertene in the celestial sphere within a few hundred thousand miles. That, too, he filed away in his memory along with the course of the wanderer.

He learned that his place of convalescence was no hospital, but Thomakein's estate. It staggered him. Thomakein was—must be—a veritable dynamo of energetic mentality to have the variety of interests as reflected in the trappings about the estate. The huge library, the observatory, the laboratories. How many of the things he saw and studied were Thomakein's personal property he would never know; though he did know that some of them came from museums and institutes across the planet.

He wondered about Thomakein. He had never seen his saviour since his mind had come back. He recalled vague things, but nothing cogent. He asked Charalas about Thomakein.

"Thomakein's main problem is Sol," explained Charalas. "A problem which you have made easy for him. However, he is on the derelict, studying the findings there. A warship is a most interesting museum of the present, you know. Often things of less than perfect operation are there; things that will eventually become perfected and established into private use. It is almost a museum of the future. Thomakein will learn much there and he has been commissioned to remain on the derelict until he has catalogued every item on it."

"Lone life, isn't it?" asked Guy.

"He has friends. Last I heard from him, he had sealed the usable portion of the derelict against the void, and was turning the course to bring it toward Ertene. Eventually the wreck will circle Ertene. Perhaps we may attempt to land it here."

"It'll be a nice museum piece," said Guy, "but it will not endear you to those of Mars."

"I know. Of course if we accept Sol's offer, we will destroy it completely."

"Keep it," said Guy, shrugging his shoulders. "Ertene will find little in common with Mars. It will be Terra and Ertene; together we will form the nucleus of Solar power."

"So?"

"Naturally. Ertene and Terra are the most alike, even to the flora and fauna."

"I see."

Charalas let the matter drop as he did before. Guy tried to open the line of thought again, but met with no success. It was not a matter of indifference to Guy's arguments, but more a complete disinclination to make any sort of statement prior to the decision of the Council of Ertene. Realizing that this decision was one of the single-try variety, Guy studied hard during the next few days. There would be no appeal even though he tried to get another hearing during the rest of his life.

He wondered how soon it would be.

Charalas landed on Thomakein's estate in a small flier and asked Guy if he would like to see the famous Hall of History. They flew a quarter of the way around the planet, and during the trip, Charalas pointed out scenes of interest. It was enlightening to Guy, who hadn't seen anything beyond a few miles of Thomakein's estate. There were farms laid out on the production-line scale while the cities and towns that housed the farmers were sprawling, rustic villages of simple beauty. The larger cities had evolved from the square-block and rubber-stamp home kind to specialized aggregations in which the central, business sections were close-knit while the residences were widespread and well apart, giving each family adequate breathing room.

"The railroad," smiled Charalas, "is still with us. It will never leave, because shipments of heavy machinery of low necessity can be transported cheaper that way. Like the barges that ply the rivers with coal, ore, and grain, they are powered with adaptations of the space drive, but they are none the less barges or trains."

"They've found that, too," laughed Guy. "There is little economic value in trying to ship a million tons of coal by flier."

"Normally, you should say. The slowest conveyor system is rapid if the conveyor is always filled and the material is not perishable. Coal and ore have been here for eons. Therefore it is no hardship to wait for six weeks while a given ton of ore gets across the continent, provided that the user can remove a ton of ore from the conveying system simultaneously with the placement of another ton that will not get there for six weeks."

"Sounds correct, though I've never thought of it in that manner," said Guy thoughtfully. "But that must be why it is done. We hull ore across space untended, and in pre-calculated orbits, picking it up at Terra from Pluto, for instance. The driverless and crewless hull is packed with ore, towed into space by a space tug and set into its orbit, the tug then returning to the shipping area to await the next hull. The hull may take a couple of years to get to Terra, but when it does, it begins to emit a finder-signal and Terran space tugs pick the hull up and lower it to Terra. The hulls are returned with unperishable supplies to the Plutonian miners."

"We hadn't the necessity of applying that thought to space shipping," answered Charalas. "Tonis, the larger moon, is so close that special shipping methods are not needed. We have but a few colonists there, most of which are members of the laboratory staff."

"You've found moon laboratories essential in space work, too?" asked Guy.

"Naturally. Tonis is airless and upon it is the Ertinian astronomical laboratory."

"Moons—even sterile moons—are good for that," said Guy. "They—Say, Charalas, what is that collection of buildings below here? They look like something extra-special."

"They are. That is the place we're going to see."

Charalas put the flier into a steep dive and landed in the open space between the buildings. They entered the long, low building at the end opposite the most ornate building of the seven that surrounded the landing area and Charalas told the receptionist that they were expected.

The long hall was excellently illuminated, and on either side of the corridor were murals; great twelve-foot panels of rare color and of photographic detail. Upon close examination they proved to be paintings.

The first panel showed an impression of the formation of Ertene, along with the other eleven planets of Ertene's parent sun. It was colorful, and impressionistic in character rather than an attempt to portray the actual cataclysm that formed the planets. The next few panels were of geologic interest, giving the impressions of Ertene through the long, geologic periods. There were dinosaur-picturizations next, and the panels brought them forward in irregular steps through the carboniferous; through the glacial ages; through the dawn ages; and finally into the coming of man to power.

The next fourteen panels were used in the rise of man on Ertene from the early ages to full, efficient civilization. They were similar to a possible attempt to portray a similar period on Terra, showing wars, life in the cities of power during the community-power ages, and the fall of several powerful cities.

Then the rise of widespread government came with its more closely-knit society made possible by better means of communication and transportation. This went on and on until the facility of the combining factors made separate governments on Ertene untenable, and there were seven great, fiery panels of mighty, widespread wars.

"Up to here, it is similar to ours," commented Guy.

"And here it changes," said Charalas. "For the next panels show the impending doom of Ertene's parent sun. The problem of space had been conquered but the other planets were of little interest to Ertene. We fought about four interplanetary wars as you see here, all against alien races. Then came trouble. The odd chance of a run-away star coming near Ertene did happen, and we faced the decision of living near an unstable sun for centuries, for our astronomers calculated that the two stars would pass close enough to cause upheavals in the suns that would result in instability for thousands, perhaps millions of years."

"Instability might not have been so bad," said Guy thoughtfully, "if it could be predicted. No, I'm not speaking in riddles," he laughed. "I may sound peculiar, saying that it would be possible to predict instability. But a regular variable of the cepheid type is predictable instability."

"True. But we had no basis for prediction. After all, it would have been taking a chance. Suppose that the instability had caused a nova? Epitaphs are nice but none the less final. We left hundreds of years before the solar proximity. Now we know that we might have survived, but as you know, we can not swerve Ertene's course readily and though we are slowly turning, the race may have died out and gone for a galactic eon before we could return. Once the race dies out—or the interest in returning to a certain sun back there in the depths of the galaxy dies—we will cease to turn. We may find a haven somewhere, before then."

"You were speaking of years," said Guy. "Was that a loose reference or were you approximating my conception of a year?"

"A year is a loose term indeed, no matter by whom it is used," said Charalas. "To you, it is three hundred and sixty-five, and about a quarter, days. A day is one revolution of Terra. From Mars, say, a Terran year is something else entirely. Mars, of course, is not too good an example for its sidereal day is very close to Terra's. But your Venus, with its eighteen hour day—eighteen Terran hours—sees Terra's year as four hundred eighty-six, plus, days. On Ertene, we have no year. We had one, once. It was composed of four hundred twelve point seven zero four two two nine three one days, sidereal. Now, our day is different, since the length of the solar day depends upon the progression of the planet about its luminary. Our luminary behaves as a moon with a high ecliptic-angle as I have explained. No, Guy, I have been mentally converting my year to your year, by crude approximation."

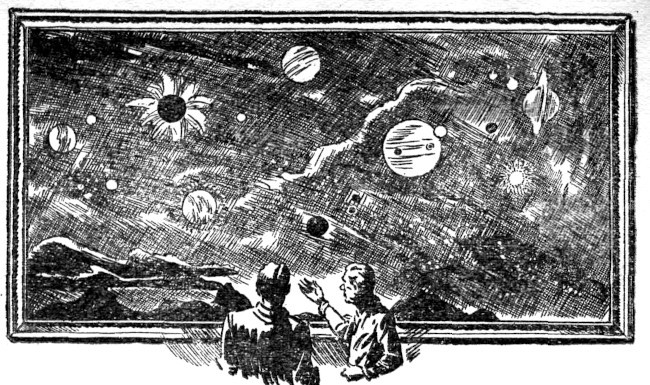

The next panel was an ornate painting of the Ertinian system, showing—out of scale for artistic purpose—the planets and sun, with Ertene drawing away in a long spiral.

"For many years we pursued that spiral, withdrawing from the sun by slow degrees. Then we broke free." Charalas indicated the panel which showed Ertene in the foreground while the clustered system was far behind.

They passed from panel to panel, all of which were interesting to Guy Maynard. There was a series of the first star contacted by Ertene. It was a small system, cold and forbidding, or hot and equally forbidding. The outer planets were in the grip of frozen air, and the inner planets bubbled in moltenness "This system was too far out of line to turn. It was our first star, and we might have stayed in youthfulness. Now, we know better."

The next panel showed a dimly-lighted landscape; a portrayal of Ertene without its synthetic sun. The luminous sky was beautiful in a nocturnal sort of way; to Guy it was slightly nostalgic for some unknown reason, at any rate it was the soul of sadness, that landscape.

Charalas shook his head and then smiled. He led Guy to the next panel, and there was a portrait of an elderly man, quite a bit older than Charalas though the neuro-surgeon was no young man. "Timalas," said Charalas proudly. "He gave us the next panel."

The following panel was a similar scene to the dismal one, but now the same trees and buildings and hills and sky were illuminated by a sun. It was a cheerful, uplifting scene compared to the soul-clouding darkness.

Ertene was a small sphere encircled by a band of peaceful black in a raving sky of fire and flame. Three planets fought in the death throes, using every conceivable weapon. Space was riven with blasting beams of energy and segregated into square areas by far-flung cutting planes. Raging energy consumed spots on each of the planets and the corners of the panel were tangled masses of broken machinery and burning wreckage, and the hapless images of trapped men. But Ertene passed through this holocaust unseen because of Timalas' light-shield.

"He saved us that, too," said Charalas reverently. "We could not have hoped to survive in this. Our science was not up to theirs, though the aid of a derelict or two gave us most of their science of war. I doubt that Terra herself could have survived. We passed unseen, though we worried for a hundred years lest they find us."

A race of spiders overran four of the planets of the next panel. They were unintelligent, there was a questioning air to the panel, as though posing the query as to how this race of spiders had crossed the void. And the picture of an Ertinian dying because contact with one of the spiders indicated their reason for not remaining.

The next panel showed a whole system with ammoniated atmosphere. "It was before the last panel," said Charalas, "that Ertene became of age as far as the wanderlust went. We knew that we could survive. We wanted no system wherein Ertene would be alone. Of what use to civilization would a culture be if its people could never leave the home planet?"

"No," agreed Guy. "Once a race has conquered space, they must use it. It would restrict the knowledge of a race not to use space."

"So we decided never to accept a system wherein we could not travel freely to other planets. Who knows, but the pathway to the planets may be but the first, faltering step to the stars?"

"We'd never have reached the planets if we'd never flown on the air," agreed Guy.

"We prefer company, too," smiled Charalas, pointing out the next panels. One was of a normal system but in which the life was not quite ready for the fundamentals of science and therefore likely to become slave-subject to the Ertinian mastery. The next was a system in which the intelligent life had overrun the system and had evolved to a high degree—and Ertene might have been subject to them if they had remained. "Unfortunately we could learn nothing from them," said the Ertinian. "It was similar to an ignorant savage trying to learn something from us."

Then they came to a panel in which there were ten planets. It was a strange collection of opposites all side by side. There were several races, some fighting others, some friendly with others. Plenty and poverty sat hand in hand, and in one place a minority controlled the lives of the majority while professing to be ruled by majority-rule. Men strived to perfect medicine and increase life-expectancy and other men fought and killed by the hundreds of thousands. A cold and forbidding planet was rich in essential ore, and populated by a semi-intelligent race of cold-blooded creatures. The protectors of these poor creatures were the denizens of a high civilization, who used them to fight their petty fights for them, under the name of unity. For their trouble, they took the essential ores to their home planet and exchanged items of dubious worth. The trespass of a human by the natives of a slightly populated moon caused the decimation of the natives, while the humans used them by the hundreds in vivisection since their anatomy was quite similar to the human's.

"Where is Ertene?" asked Guy.

"Ertene is not yet placed," said Charalas.

"No?" asked Guy in wonder.

"No," said Charalas with a queer smile. "Ertene is still not sure of her position. You see, Guy, that system is Sol."

Guy Maynard stood silent, thinking. It was a blow to him, this picturization of the worlds of Sol as seen through the eyes of a totally alien race. His own feelings he analyzed briefly, and he knew that in his own heart, he was willing to shade any decisions concerning the civilization of Ertene in the Ertinian favor; had any dispute between Ertene and a mythical dissenter, Guy would have had his decision weighted in favor of the wanderer for one reason alone.

Ertinians were human to the last classification!

Guy smiled inwardly. "Blood is thicker than water," he thought to himself, and he knew that while the old platitude was meant to cover blood-relations who clung together in spite of close bonds with friends not of blood relationship, it could very well be expanded to cover this situation. Obviously he as a Terran would tend to support a human race against a merely humanoid race. He would fight the Martians for Ertene just as he would fight them for Terra.

Fighting Ertene itself was unthinkable. They were too human; Ertene was too Terran to think of strife between the two worlds. Being of like anatomy, they would and should cling together against the whole universe of alien bodies.

But—

He had spoken to Charalas, to the nurses, to the groundkeepers, and to the scientists who came to learn of him and from him. He had told them of Terra and of the Solar System. He had explained the other worlds in detail and his own interpretation of those other cultures.

And still they depicted Terra in no central light. Terra did not dominate the panel. It vied with the other nine planets and their satellites for the prominence it should have held.

What was wrong?

Knowing that he would have favored Ertene for the anatomical reasons alone, Guy worried. Had his word-picture been so poor that Ertene gave the other planets their place in the panel in spite of the natural longing to place their own kind above the rest?

"I should think—" he started haltingly, but Charalas stopped him.

"Guy Maynard, you must understand that Ertene is neutral. Perhaps the first neutral you've ever seen. Believe that, Guy, and be warned that Ertene is capable of making her own, very discerning decision."

Guy did not answer. He knew something else, now. Ertene was not going to be easily convinced that Sol was the place for them. She was neutral, yes, but there was something else.

Ertene had the wanderlust!

For eons, Ertene had passed in her unseen way through the galaxy. She had seen system after system, and the lust for travel was upon her. Travel was her life, and had been for hundreds of generations.

Her children had been born and bred in a closed system, free from stellar bonds. Their history was a vast storehouse of experience such as no other planet had ever had. Every generation brought them to another star and each succeeding generation added to the wisdom of Ertene as it extracted or tried to extract some bit of knowledge from each system through which Ertene passed.

With travel her natural life, the wandering planet would be loath to cease her transient existence.

Like a man who has spent too many years in bachelorhood, flitting like a butterfly from lip to lip, Ertene had become inured to a single life. It would take a definite attraction to swerve her from her self-sufficiency.

These things came to Maynard as he stood in thought. He knew then that his was no easy job. Not the simple proposition of asking Ertene to join her own kind in an orbit about Sol. Not the mere signing of a pact would serve. Not the Terran-shaded history of the worlds of Sol with the Terran egotism that did not admit that Terra could possibly be wrong.

Ertene must be made to see the attractiveness of living in Maynard's little universe. It must be made more attractive than the interesting possibilities offered by the unknown worlds that lie ahead on her course through the galaxy.

All this plus the natural reticence of Ertene to become involved in a system that ran rife with war. The attractiveness of Sol must be so great that Ertene would remain in spite of war and alien hatred.

And Maynard knew in his heart that he was not the one to sway them easily. Part of his mind felt akin to their desire to roam. Even knowing that he would not live on Ertene to see the next star he wanted to go with them in order that his children might see it.

And yet his honor was directed at the service of Terra. His sacred oath had been given to support and strive to the best interest of Terra and Sol.

He put away the desire to roam with Ertene and thought once more of the studying he must do to convince Ertene of the absolute foolishness of continuing in their search for a more suitable star than Sol about which to establish a residence.

Maynard turned to Charalas and saw that the elderly doctor had been watching him intently. Before he could speak, the Ertinian said: "It is a hard nut to crack, lad. Many have tried but none have succeeded. Like most things that are best for people, they are the least exciting and the most formal, and people do not react cheerfully to a formal diet."

Maynard shook his head. "But unlike a man with ulcers, I cannot prescribe a diet of milk lest he die. Ertene will go on living no matter whether I speak and sway them or whether I never say another word. I am asked to convince an entire world against their will. I can not tell them that it is the slightest bit dangerous to go on as they have. In fact, it may be dangerous for them to remain. In all honesty, I must admit that Terra is not without her battle scars."

Charalas said, thoughtfully: "Who knows what is best for civilization? We do not, for we are civilization. We do as we think best, and if it is not best, we die and another civilization replaces us in Nature's long-time program to find the real survivor."

He faced the panel and said, partly to himself and partly to Guy:

"Is it best for Ertene to go on through time experimenting? Gathering the fruits of a million civilizations bound forever to their stellar homes because of the awful abyss between the stars? For the planets all to become wanderers would be chaos.

"Therefore is it Nature's plan that Ertene be the one planet to gather unto herself the fruit of all knowledge and ultimately lie barren because of the sterility of her culture? Are we to be the sponge for all thought? If so, where must it end? What good is it? Is this some great master plan? Will we, after a million galactic years, reach a state where we may disseminate the knowledge we have gained, or are we merely greedy, taking all and giving nothing?

"What are we learning? And, above all, are we certain that Ertene's culture is best for civilization? How may we tell? The strong and best adapted survive, and since we are no longer striving against the lesser forces of Nature on our planet, and indeed, are no longer striving against those of antisocial thought among our own people—against whom or what do we fight?

"Guy Maynard, you are young and intelligent. Perhaps by some whimsy of fate you may be the deciding factor in Ertene's aimlessness. We are here, Guy. We are at the gates to the future. My real reason for bringing you to the Center of Ertene is to have you present your case to the Council."

He took Guy's arm and led him through the door at the end of the corridor. They went into the gilt-and-ivory room with the vast hemispherical dome and as the door slowly closed behind them, Guy Maynard, Terran, and Charalas, Ertinian, stood facing a quarter-circle of ornate desks behind which sat the Council.

Obviously, they had been waiting.

IV.

Guy Maynard looked reproachfully at Charalas. He felt that he had been tricked, that Charalas had kicked the bottom out of his argument and then had forced him into the debate with but an impromptu defense. He wondered how this discussion was to be conducted, and while he was striving to collect a lucid story, part of his mind heard Charalas going through the usual procedure for recording purposes.

"Who is this man?"

"He is Junior Executive Guy Maynard of the Terran Space Patrol."

"Explain his title."

"It is a rank of official service. It denotes certain abilities and responsibilities."

"Can you explain the position of his rank with respect to other ratings of more or less responsibility?"

Charalas counted off on his fingers. "From the lowest rank upward, the following titles are used: Junior Aide, Senior Aide, Junior Executive, Senior Executive, Sector Commander, Patrol Marshal, Sector Marshal, and Space Marshal."

"These are the commissioned officers? Are there other ratings?"

"Yes, shall I name them?"

"Prepare them for the record. There is no need of recounting the noncommissioned officials."

"I understand."

"How did Guy Maynard come to Ertene?"

"Maynard was rescued from a derelict spaceship."

"By whom?"

"Thomakein."

"Am I to assume that Thomakein brought him to Ertene for study?"

"That assumption is correct."

"The knowledge of the system of Sol is complete?"

"Between the information furnished by Guy Maynard and the observations made by Thomakein, the knowledge of Sol's planets is sufficient. More may be learned before Ertene loses contact, but for the time, it is adequate."

"And Guy Maynard is present for the purpose of explaining the Terran wishes in the question of whether Ertene is to remain here?"

"Correct."

The councilor who sat in the center of the group smiled at Guy and said: "Guy Maynard, this is an informal meeting. You are to rest assured we will not attempt to goad you into saying something you do not mean. If you are unprepared to answer a given question, ask for time to think. We will understand. However, we ask that you do not try to shade your answers in such a manner as to convey erring impressions. This is not a court of law; procedure is not important. Speak when and as you desire and understand that you will not be called to account for slight breaches of etiquette, since we all know that formality is a deterrent to the real point in argument."

Charalas added: "Absolute formality in argument usually ends in the decision going to the best orator. This is not desirable, since some of the more learned men are poor orators, while some of the best orators must rely upon the information furnished them by the learned."

The center councilor arose and called the other six councilors by name in introduction. This was slightly redundant since their names were all present in little bronze signs on the desks. It was a pleasantry aimed at putting the Terran at ease and offering him the right to call them by name.

"Now," said Terokar, the center one, "we shall begin. Everything we have said has been recorded for the records. But, Guy, we will remove anything from the record that would be detrimental to the integrity of any of us. We will play it back before you leave and you may censor it."

"Thank you," said Guy. "Knowing that records are to be kept as spoken will often deter honest expression."

"Quite true. That is why we permit censoring. Now, Guy, your wishes concerning Ertene's alliance with Sol."

"I invite Ertene to join the Solar System."

"Your invitation is appreciated. Please understand that the acceptance of such an invitation will change Ertene's social structure forever, and that it is not to be taken lightly."

"I realize that the invitation is not one to accept lightly. It is a large decision."

"Then what has Sol to offer?"

"A stable existence. The commerce of an entire system and the friendship of another world of similar type in almost every respect. The opportunity to partake in a veritable twinship between Ertene and Sol, with all the ramifications that such a brotherhood would offer."

"Ertene's existence is stable, Guy. Let us consider that point first."

"How can any wandering program be considered stable?"

"We are born, we live, and we die. Whether we are fated to spend our lives on a nomad planet or ultimately become the very center of the universe about which everything revolves, making Ertene the most stable planet of them all, Ertinians will continue living. When nomadism includes the entire resources of a planet, it can not be instable."

"Granted. But do you hope to go on forever?"

"How old is your history, Guy?"

"From the earliest of established dates, taken from the stones of Assyria and the artifacts of Maya, some seven thousand years."

Charalas added a lengthy discussion setting the length of a Terran year.

"Ertinian history is perhaps a bit longer," said Terokar. "And so who can say 'forever'?"

"No comment," said Guy with a slight laugh. "But my statements concerning stability are not to be construed as the same type of instability suffered by an itinerant human. He has no roots, and few friends, and he gains nothing nor does he offer anything to society. No, I am wrong. It is the same thing. Ertene goes on through the eons of wandering. She has no friends and no roots and while she may gain experience and knowledge of the universe just as the tramp will, her ultimate gain is poor and her offering to civilization is zero."

"I dispute that. Ertene's life has become better for the experience she has gained and the knowledge, too."

"Perhaps. But her offering to civilization?"

"We are not a dead world. Perhaps some day we may be able to offer the storehouses of our knowledge to some system that will need it. Perhaps we are destined to become the nucleus of a great, galactic civilization."

"Such a civilization will never work as long as men are restrained as to speed of transportation. Could any pact be sustained between planets a hundred light-years apart? Indeed, could any pact be agreed upon?"

"I cannot answer that save to agree. However, somewhere there may be some means of faster-than-light travel and communication. If this is found, galactic-wide civilization will not only be possible but a definite expectation."

"You realize that you are asking for Ertene a destiny that sounds definitely egotistic?"

"And why not? Are you not sold on the fact that Terra is the best planet in the Solar System?"

"Naturally."

"Also," smiled Charalas, "the Martians admit that Mars is the best planet."

"Granted then that Ertene is stable. Even granting for the moment that Ertene is someday to become the nucleus of the galaxy. I still claim that Ertene is missing one item." Guy waited for a moment and then added: "Ertene is missing the contact and commerce with other races. Ertene is self-sufficient and as such is stagnant as far as new life goes. Life on Ertene has reached the ultimate—for Ertene. Similarly, life on Terra had reached that point prior to the opening of space. Life must struggle against something, and when the struggle is no longer possible—when all possible obstruction has been circumvented—then life decays."

"You see us as decadent?"

"Not yet. The visiting of system after system has kept you from total decadence. It is but a stasis, however. Unless one has the samples of right and wrong from which to choose, how may he know his own course?"

"Of what difference is it?" asked the councilor named Baranon. "If there is no dissenting voice, if life thrives, if knowledge and science advance, what difference does it make whether we live under one social order or any other? If thievery and wrongdoing, for instance, could support a system of social importance, and the entire population lives under that code and thrives, of what necessity is it to change?"

"Any social order will pyramid," said Guy. "Either up or down."

"Granted. But if all are prepared to withstand the ravages of their neighbors, and are eternally prepared to live under constant strife, no man will have his rights trod upon."

"But what good is this eternal wandering? This everlasting eye upon the constantly receding horizon? This never ending search for the proper place to stop in order that this theoretical galactic civilization may start? At Ertene's state of progress, one place will be as good as any other," said Guy.

"Precisely, except that some places are definitely less desirable. Recall, Guy, that Ertene needs nothing."

"I dispute that. Ertene needs the contact with the outside worlds."

"No."

"You are in the position of a recluse who loves his seclusion."

"Certainly."

"Then you are in no position to appreciate any other form of social order."

"We care for no other social order."

"I mentioned to Charalas that in my eyes, you are wrong. That I am being asked to prescribe for a patient who will not die for lack of my prescription. I can not even say that the patient will benefit directly. My belief is as good as yours. I believe that Ertene is suffering because of her seclusion and that her peoples will advance more swiftly with commerce between the planets—and once again in interstellar space, Ertene will have no planets with which to conduct trade."

"And Sol, like complex society, will never miss the recluse. Let the hermit live in his cave, he is neither hindering nor helping civilization."

"Indirectly, the hermit hinders. He excites curiosity and the wonder if a hermit's existence might not be desirable and thus diverts other thinkers to seclusion."

"But if the hermit withdraws alone and unnoticed, no one will know of the hermitage, and then no one will wonder."

"But I know, and though no one else in the Solar System knows, I am trying to bring you into our society. I have the desire of brotherhood, the gregarious instinct that wants to be friend with all men. It annoys me—as it annoys all men—to see one of us alone and unloved by his fellows. I have a burning desire to have Ertene as a twin world with Terra."

"But Ertene likes her itinerant existence. The fires that burn beyond the horizon are interesting. Also," smiled Terokar, "the grass is greener over there."