Life's Little Stage

Agnes Giberne

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

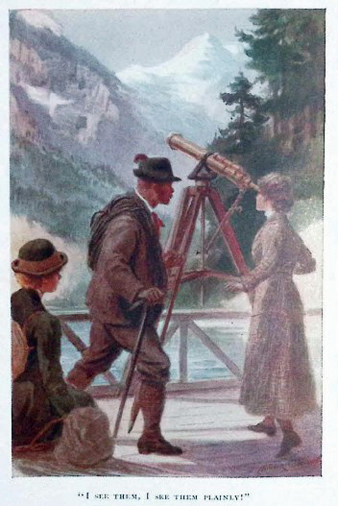

"I SEE THEM, I SEE THEM PLAINLY!"

LIFE'S LITTLE STAGE

BY

AGNES GIBERNE

AUTHOR OF

"SUN, MOON AND STARS," "THIS WONDER-WORLD,"

"STORIES OF THE ABBEY PRECINCTS," ETC., ETC.

"Who can over-estimate the value of these little Opportunities?

How angels must weep to see us throw them away!

. . . And how can we ever expect to meet the great trials

worthily, unless we learn discipline by those which to others

may seem but trifles?"—ANON.

LONDON

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

4 BOUVERIE STREET AND 65 ST. PAUL'S CHURCHYARD, E.C.

1913

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Little 'Why-Because'

This Wonder-World

Gwendoline

The Hillside Children

Stories of the Abbey Precincts

Anthony Cragg's Tenant

Profit and Loss; or, Life's Ledger

Through the Linn

Five Little Birdies

Next-Door Neighbours

Willie and Lucy at the Sea-side

LONDON: THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

FOREWORD

THERE are many girls who, on leaving School for Home-life, find the year or two following rather "difficult." They seem often not quite to know what to do with themselves, with their time, with their gifts; and they are apt to fall into some needless mistakes for want of a guiding hand. My wish, in writing this tale, has been to give such girls a little help. It may be that one here or there, in reading it, will find out how to avoid such mistakes from the struggles, the defeats, and the non-defeats of Magda Royston.

AGNES GIBERNE.

EASTBOURNE.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

I. GOOD-BYE TO SCHOOL

II. WHAT WAS THE USE?

III. ROBERT

IV. THE INEFFABLE PATRICIA

V. UNWELCOME NEWS

VI. SWISS ENCOUNTERS

VII. A MOUNTAIN HUT BY NIGHT

VIII. IN AN AVALANCHE

IX. FRIENDS IN PERIL

X. THE RESCUED MAN

XI. PATRICIA'S AFFAIRS

XII. AN OPPORTUNITY LOST

XIII. VIRGINIA VILLA

XIV. A REVERSION OF THOUGHT

XV. LIFE'S ONWARD MARCH

XVI. THE THICK OF THE FIGHT

XVII. ABOUT TRUE SERVICE

XVIII. TAKEN BY SURPRISE

XIX. IF HE SHOULD COME!

XX. THROUGH AN ORDEAL

XXI. AND AFTERWARDS

XXII. "COULDN'T BE TIED!"

XXIII. HERSELF OR HER FRIEND?

XXIV. SOMEBODY'S LOOSE ENDS

XXV. MAGDA'S OLD CHUM

XXVI. WHERETO THINGS TENDED

XXVII. WHAT PATRICIA WANTED

XXVIII. WOULD SHE GIVE IN?

XXIX. SO AWFULLY SUDDEN!

XXX. IF ONLY SHE HAD—!

XXXI. LOST LOOKS

XXXII. AFTER SEVEN MONTHS

XXXIII. THIS GLORIOUS WORLD!

XXXIV. ONCE MORE TO THE TEST

LIFE'S LITTLE STAGE

CHAPTER I

GOOD-BYE TO SCHOOL

"SOME girls would be glad in your place."

"It's just the other way with me."

"Not that you have not been happy here. I know you have. Still—home is home."

"This is my other home."

Miss Mordaunt smiled. It was hardly in human nature not to be gratified.

"If only I could have stayed two years longer! Or even one year! Father might let me. It's such a horrid bore to have to leave now."

"But since no choice is left, you must make the best of things."

The two stood facing one another in the bow-window of Miss Mordaunt's pretty drawing-room; tears in the eyes of the elder woman, for hers was a sympathetic nature; no tears in the eyes of the girl, but a sharp ache at her heart. Till the arrival of this morning's post she never quite lost hope, though notice of her removal was given months before. A final appeal, vehemently worded, after the writer's fashion, had lately gone; and the reply was decisive.

Many a tussle of wills had taken place during the last four years between these two; and a time was when the pupil indulged in hard thoughts of the kind Principal. But Miss Mordaunt possessed power to win love; and though she found in Magda Royston a difficult subject, she conquered in the end. Out of battling grew strong affection—how strong on the side of Magda perhaps neither quite knew until this hour.

"There isn't any 'best.' It's just simply horrid."

"Still, if you are wanted at home, your duty lies there."

"I'm not. That's the thing. Nobody wants me. Mother has Penrose; and father has Merryl; and Frip—I mean, Francie—is the family pet. And I come in nowhere. I'm a sort of extraneous atom that can't coalesce with any other atom." A tinge of self-satisfaction crept into the tone. "It's not my fault. Nobody at home needs me—not one least little bit. And there isn't a person in all the town that I care for—not one blessed individual!"

Miss Mordaunt seated herself on the sofa, drawing the speaker to her side, with a protesting touch.

"There isn't. Pen snaps them all up. And if she didn't, it would come to the same thing. I'm not chummy with girls—never was. I had a real friend once; but he was a boy; and boys are so different. Ned Fairfax and I were immense chums; but he was years and years older than me; and he went right away when I was only eleven. I've never set eyes on him since, and I don't even know now what has become of him. Only I know we should be friends again—directly—if ever we met! The girls and I get on well enough here, but we're not friends."

"Except Beatrice."

"Bee is a little dear, and I dote on her; and she worships the ground I tread on. But after all—though she is more than a year older, she always seems the younger. And I'm much more to her than she is to me. Don't you see? I wouldn't say that to everybody, but it's true. I want something more than that, if it is to satisfy! Bee looks up to me. I want some one that I can look up to."

"There is much more in Bee than appears on the surface."

"I dare say. She pegs away, and gets on. She'll be awfully useful at home. And in a sort of way she is taking."

"People find her extremely taking. She is a friend worth having and worth keeping. But I hope you are going to have friends in Burwood."

"There's nobody. Oh well, yes, there is one—but she doesn't live there. She only comes down to a place near for a week or ten days at a time. Her name is Patricia, and she is a picture! I've seen her just three times, and I fell in love straight off. But I haven't a ghost of a chance. Everybody runs after her. Oh, I shall get on all right. There's Rob, you know. He and I have always been cronies; and it's quite settled that I shall keep house for him some day. Not till he gets a living; and that won't be yet. He was only ordained two years ago."

"I should advise you not to build too much on that notion. Your brother may marry."

Magda's eyes blazed. They were singular golden-brown eyes, with a reddish tinge in the iris, matching her hair.

"You don't know Rob! He always says he never comes across any girls to be compared with his sisters. And I always was his special! He promised—years ago—that I should live with him by-and-by. At least—if he didn't exactly promise, he said it. Father jeers at the idea, but Rob means what he says."

Miss Mordaunt hesitated to throw further cold water. Life itself would bring the chill splash soon enough.

"Well—perhaps," she admitted. "Only, it is always wiser not to look forward too confidently. Things turn out so unlike what one expects beforehand. Have you not found it so?"

"I'm sure this won't. It will all come right, I know. But just imagine father talking about my having 'finished my education.' Oh dear me, if he would but understand! He says his own sisters finished theirs at seventeen, and he doesn't see any need for new-fangled ways. You may read it!" Magda held out the sheet with an indignant thrust. "As if it mattered what they used to do in the Dark Ages."

Miss Mordaunt could not quite suppress another smile. She read the letter and gave it back.

"That settles the matter, I am afraid. I see that your father wants his daughter."

"He doesn't!" bluntly. "He wants nobody except Merryl. 'Finished my education' indeed! Why, I'm not seventeen till next month; and I'm only just beginning to know what real work means."

Miss Mordaunt could have endorsed this; but an interruption came. She was called away; and Magda wandered to one of the class-rooms, where, as she expected, she found a girl alone bending over a desk, hard at work—a girl nearly as tall as herself, but so slight in make that people often spoke of her as "little;" the more so, perhaps, from her gentle retiring manner, and from the look of wistful appeal in her brown eyes. It was a pale face, even-featured, with rather marked dark brows and brown hair full of natural waves. As Magda entered she jumped up.

"I've been wanting to see you, Magda. Only think—"

"I went to tell Miss Mordaunt—father has written at last."

"Has he? And he says—?"

"I'm to go home for good at the end of the term."

"Then we leave together, after all."

"It's right enough for you. You've had an extra year. But I do hate it—just as I am getting to love work—to have to stop."

"You won't stop. You are so clever. You will keep on with everything."

"It can't be the same—working all alone."

Beatrice looked sympathetic, but only remarked—"I have heard from my mother too. And only think! We are to leave town. Not now, but some time next year; when the lease of our house is up. Guess where we may perhaps live!"

"Not—Burwood!" dubiously.

Bee clapped joyous hands.

"What can have made your mother think of such a thing?"

"Why, Magda! Wouldn't you be glad to have us?"

"Of course. But I mean—how did it come into her head?"

"I put the notion there. Wouldn't you have done it in my place? London never has suited her; and our doctor advises the country. And I said something in my last about Burwood—not really thinking that anything would come of it. But mother has quite taken to the idea. She used to stay near, sometimes, when she was a child; and she remembers well how pretty the walks and drives were. It would make all the difference to me if we were near to you. I should not mind so very much then having to leave Amy."

Magda was not especially fond of hearing about this other great friend—Amy Smith. Whatever her estimate might be, in the abstract, of the value of Bee, she liked to have the whole of her; not to share her with somebody else. Certainly not with a "Miss Smith!"

"You see, I've been near Amy all my life; and she is so good to me—too good! She's years older, but we are just like sisters, and I don't know how I shall get on without her. But if it is to come near you, dear, saying good-bye won't be quite so hard."

"It will be frightfully nice if you do. We can do no end of things together. I suppose it's not settled yet."

"No; only, if mother once takes to a plan, she doesn't soon give it up. So I'm very hopeful. Just think! If I were always near you! And you were always coming in and out!"

"It would be frightfully nice!" repeated Magda, throwing into her voice what Bee would expect to hear. But when she strolled away, she questioned within herself—was she glad? Would she be more disappointed or more relieved if the scheme fell through?

The notion of introducing Beatrice Major to her home-circle did not quite appeal to her. The Roystons held their heads high, and moved in county circles, and were extremely particular as to whom they deigned to know. Bee herself was the dearest little creature—pretty and lovable, sweet and kind; but she had been only two years in the school, and Magda had met none of Bee's people. They might very easily fail to suit her people.

Beatrice, it was true, never seemed to mind being questioned about her home and connections; but it was equally true that she never appeared to have very much to say—at least of any such particulars as would impress the Royston imagination; and this was suggestive. Magda had heard so much all her life about people's antecedents, that she might be excused for feeling nervous. She had seen a photo of Bee's mother, and thought her a very unattractive person; also a photo of Amy Smith, which was worse still. She knew that Mrs. Major could not be too well off, for Bee's command of pocket-money was by no means plentiful, and her wardrobe was limited.

They would probably live in some poky little house. And though Magda could talk grandly about not caring what other people thought, and though personally she would not perhaps mind about the said house, yet she would mind extremely if her own particular friend were looked down upon by her home-folks. The very idea of Pen's air of mild disdain stung sharply.

So altogether she felt that, if the plan failed, she would not be very sorry. But Bee might on no account guess this.

Several weeks later came the day of parting; and once more Magda stood before Miss Mordaunt with a lump in her throat.

"You will have to work steadily, if you do not mean to lose all you have gained, Magda."

"I know. I shall make a plan for every day, and stick to it."

"Except when home duties come between."

"I've no home duties. Pen goes everywhere with mother, and Merryl does all the little useful fidgets. There's nothing left for me. Nobody will care what I'm after."

Miss Mordaunt studied the impressionable face. Some eager thought was at work below the surface.

"What is it, my dear?"

"You always know when I've something on my mind. I've been thinking a lot lately. Miss Mordaunt, I want to do something with my life. Not just to drift along anyhow, as so many girls do. I want to make something of it. Something great, you know!"—and her eyes glowed. "Do you think I shall ever be able? Does the chance come to everybody some time or other? I've heard it said that it does."

"It may. Many miss the 'chance,' as you call it, when it does come. I should rather call it 'the opportunity.' What do you mean by 'something great'?"

"Oh—Why!—You know! Something above the common run. Like Grace Darling, or Miss Florence Nightingale, or that Duchess who stayed behind in the French bazaar to be burnt to death, so that others might escape. It was noblesse oblige with her, wasn't it? I think it would be grand to do something of that sort,—that would be always remembered and talked about."

"Perhaps so. But don't forget that what one is in the little things of life, one is also in the great things. More than one rehearsal is generally given to us before the 'great opportunity' is sent. And if we fail in the rehearsals, we fail then also."

"Yes—I know. And I do mean to work at my studies. But all the same, I should like to do something, some day, really and truly great."

Miss Mordaunt looked wistfully at the girl. "Dear Magda—real greatness does not mean being talked about. It means—doing the Will of God in our lives—doing our duty, and doing it for Him."

CHAPTER II

WHAT WAS THE USE?

MANY months later that parting interview with Miss Mordaunt recurred vividly to Magda.

"What's the good of it all, I wonder?" she had been asking aloud.

And suddenly, as if called up from a far distance, she saw again Miss Mordaunt's face, and heard again her own confident utterances.

It was a bitterly cold March afternoon. She stood alone under the great walnut tree in the back garden—which was divided by a tall hedge from the kitchen garden. Over her head was a network of bare boughs; and upon the grass at her feet lay a pure white carpet. Some lilac bushes near had begun to show promise of coming buds; but they looked doleful enough now, weighed down by snow.

She had with such readiness promised steady work in the future! And she had meant it too.

The thing seemed so easy beforehand. And for a time she really had tried. But she had not kept it up. She had not worked persistently. She had not "stuck" to her plans. The contrast between intention and non-fulfilment came upon her now with force.

Six months had gone by of home-life, of emancipation from school control. Six months of aimless drifting—the very thing she had resolved sturdily against.

"Oh, bother! What's the use of worrying? Why can't I take things as Pen does? Pen never seems to mind." But she was in the grip of a cogitative mood, and thinking would not be stayed.

She had begun well enough—had planned daily two hours of music, an hour of history, an hour of literature, an hour alternately of French and German. It had all looked fair and promising. And the whole had ended in smoke.

Something always seemed to come in the way. The children wanted a ramble. Or she was sent on an errand. Or a caller came in. Or there was an invitation. Or—oftener and worse!—disinclination had her by the throat.

Disinclination which, no doubt, might have been, and ought to have been, grappled with and overcome. Only, she had not grappled with it. She had not overcome. She had yielded, time after time.

It was so difficult to work alone; so dull to sit and read in her own room; so stupid to write a translation that nobody would see; so tiresome to practice when there was none to praise or blame. Not that she liked blame; and not that she was not expected to practice; but no marked interest was shown in her advance; and she wanted sympathy and craved an object. And it was so fatally easy to put off, to let things slide, to get out of the way of regular plans. The fact that any time would do equally well soon meant no time.

This had been a typical day; and she reviewed it ruefully. A morning of aimless nothings; the mending of clothes idly deferred; hours spent in the reading of a foolish novel; jars with Penrose; friction with her mother; a sharp set-down from her father; then forgetfulness of wrongs and resentment during a romp in the snow with Merryl and Frip—till the younger girls were summoned indoors, leaving her to descend at a plunge from gaiety to disquiet. Magda's variations were many.

She stood pondering the subject—a long-limbed well-grown girl, young in look for her years, with a curly mass of red-brown hair, seldom tidy, and a pair of expressive eyes. They could look gentle and loving, though that phase was not common; they could sparkle with joy or blaze with anger; they could be dull as a November fog; they could, as at this moment, turn their regards inwards with uneasy self-condemnation.

But it was a condemnation of self which she would not have liked anybody else to echo. No one quicker, you may be sure, than Magda Royston in self-defence! Even now words of excuse sprang readily, as she stood at the bar of her own judgment.

"After all, I don't see that it is my fault. I can't help things being as they are. And suppose I had worked all these months at music and history and languages—what then? What would be the good? It would be all for myself. I should be just as useless to other people."

A vision arose of the great things she had wished to do, and she stamped the snow flat.

"It's no good. I've no chance. There's nothing to be done that I can see. If I had heaps of money to give away! Or if I had a special gift—if I could write books, or could paint pictures! Or even if my people were poor, and I could work hard to get money for them! Anything like that would make all the difference. As it is—well, I know I have brains of a sort; better brains than Pen! But I don't see what I can do with them. I don't see that I can do anything out of the common, or better than hundreds of other people do. And that is so stupid. Not worth the trouble!"

"Mag-da!" sounded in Pen's clear voice.

"She never can leave me in peace! I'm not going indoors yet."

"Mag-da!" Three times repeated, was followed by—"Where are you? Mother says you are to come."

This could not be disregarded. "Coming," she called carelessly, and in a slow saunter she followed the boundary of the kitchen garden hedge, trailed through the back yard, stopped to exchange a greeting with the house-dog as he sprang to the extent of his chain, stroked the stately Persian cat on the door-step, and finally presented herself in the inner hall.

It was one of the oldest houses in the country town of Burwood; rather small, but antique. Once upon a time it had stood alone, surrounded by its own broad acres; but things were changed, and the acres had shrunk—through the extravagance of former Roystons—to only a fair-sized garden. The rest of the land had been sold for building; and other houses in gardens stood near. In the opinion of old residents, this was no longer real country; and with new-comers, the Roystons no longer ranked as quite the most important people in the near neighbourhood. Their means were limited enough to make it no easy matter for them to remain on in the house, and they could do little in the way of entertaining. But they prided themselves still on their exclusiveness.

Penrose stood waiting; a contrast to Magda, who was five years her junior. Not nearly so tall and much more slim, she had rather pretty blue eyes and a neat figure, which comprised her all in the way of good looks. Her manner towards Magda was superior and mildly positive, though with people in general she knew how to be agreeable. Magda's air in response was combative.

"Did you not hear me calling?"

"If not, I shouldn't be here now."

"I think you need not have kept me so long."

Magda vouchsafed no excuse. "What's up?" she demanded.

"Mother wants you in the drawing-room."

"What for?"

"She found your drawers untidy."

"Of course you sent her to look at them."

"I don't 'send' mother about. And I have not been in your room to-day."

"I understand!" Magda spoke pointedly.

Penrose glanced up and down her sister with critical eyes. A word of warning would be kind. Magda seemed blissfully unconscious of her outward condition; and Pen had this moment heard a ring at the front door, which might mean callers.

"You've done the business now, so I hope you're satisfied," Magda went on. "Mother would never have thought of looking in my drawers, if you had not said something. I know! I did make hay in them yesterday, when I couldn't find my gloves, but I meant to put them straight to-night. It's too bad of you."

Pen's lips, parted for speech, closed again. If Magda chose to fling untrue accusations, she might manage for herself. And indeed small chance was given her to say more. Magda marched off, just as she was, straight for the drawing-room—her skirts pinned abnormally high for the snow-frolic; her shoes encased in snow; her tam-o'-shanter half-covering a mass of wild hair; her bare hands soiled and red with cold and scratched with brambles.

"Yes, mother. Pen says you want me."

She sent the words in advance with no gentle voice, as she whisked open the drawing-room door. Then she stopped.

Mrs. Royston, a graceful woman, looked in displeasure towards the figure in the doorway; for she was not alone.

Callers had arrived, as Pen conjectured; and through the front window might be seen two thoroughbreds champing their bits, and a footman standing stolidly. Why had Pen given no hint? How unkind! Then she recalled her own curt turning away, and knew that she was to blame.

"Really!" with a faint laugh protested Mrs. Royston.

"So I thought we would look in for five minutes on our way back from Sir John's," the elder caller was remarking in a manly voice.

She was a large woman, more in breadth and portliness than in height, and her magnificent furs made her look like a big brown bear sitting on end. Her face too was large and strongly outlined.

Magda guessed in a moment what her mother felt; for the Honourable Mrs. Framley was a county magnate; the weightiest personality in more senses than one to be found for many a mile around. A call from her was reckoned by some people as second only to a call from Royalty. The girl's first impulse was to flee; but a solid outstretched hand commanded her approach.

"Now, which of your young folks is this?" demanded Mrs. Framley, examining Magda through an eye-glass. "Let me see—you've got—how many daughters? Penrose—Magda—Merryl—Frances. I've not forgotten their names, though it's—how long?—since I was here last. Months, I'm afraid. But this is not your neat Penrose; and my jolly little friend Merryl can't have shot up to that height since I saw her; and Magda is out. Came out in the autumn, didn't she? So who is this? A niece?"

"I'm Magda," the girl said in shamefaced confession, for Mrs. Royston seemed voiceless.

Mrs. Framley leant back in her chair, and laughed till she was exhausted.

"So that's a specimen of the modern young woman, eh?"—when she could regain her voice. "My dear—" to Mrs. Royston—"pray don't apologise. It's I who should apologise. But really—really—it's irresistible." She went into another fit, and emerged from it, wheezing. "The child doesn't look a day over fifteen." The speaker wiped her eyes. "Don't send her away. Unadulterated Nature is always worth seeing—eh, Patricia?"

Magda turned startled eyes in the direction of the second caller, a girl three or four years older than herself, and the last person whom she expected to see. The last person, perhaps, whom at that moment she wished to see. For despite Magda's boasted non-chumminess with girls, this was the one girl whom she did, honestly and heartily, though not hopefully, desire for a friend. She had fallen in love at first sight with Mrs. Framley's niece, and had cherished her image ever since in the most secret recess of her heart.

"She'll think me just a silly idiotic school-girl!" flashed through Magda's mind, as she made an involuntary movement forward with extended hand—a soiled hand, as already said, scratched and slightly bleeding.

Patricia Vincent, standing thus far with amused eyes in the background, hesitated. She was immaculately dressed in grey, with a grey-feathered hat, relieved by touches of salmon-pink, and the daintiest of pale grey kid gloves. Contact with that hand did not quite suit her fastidious sense. A mere fraction of a second—and then she would have responded; but Magda, with crimsoning cheeks, had snatched the offending member away.

"I think you had better go and send Pen," interposed Mrs. Royston. Under the quiet words lay a command, "Do not come back."

Magda fled, without a good-bye, and went to the school-room, where she flung herself into an old armchair. The gas was low, but a good fire gave light; and she sat there in a dishevelled heap, weighing her grievances.

It was too bad of Pen, quite too bad, not to have warned her! And now the mischief was done. Patricia Vincent would never forget. Pen would go in and win; while she, as usual, would be nowhere in the race.

And all because she had not first rushed upstairs, to smooth her hair and wash her hands! Such nonsense!

As if Pen had not friends enough already! Just the single girl that she wanted for herself! If she might have Patricia, Pen was welcome to the rest of the world. But that was always the way! If one cared for a thing particularly, that thing was certain to be out of reach.

She was smarting still over the thought of that refused handshake; but her anger all went in the direction of Pen, not of Patricia. Pen alone was to blame!

Presently the front door was opened and shut; and then Mrs. Royston came in, moving with her usual graceful deliberation.

"What could have made you behave so, Magda?" she asked. "To come before callers in such a state!"

Magda was instantly up in arms. "Pen never told me there were callers."

"She did not know it. She would have reminded you how untidy you were—certainly in no condition to come into the drawing-room, even if I had been alone! But you show so much annoyance if she speaks."

"Pen is always in the right, of course."

"That is not the way to speak to me. I would rather have had this happen before anybody than before Mrs. Framley."

Magda shut her lips.

"Why did you not send Pen, as I told you?"

"I forgot."

"You always do forget. There is more dependence to be put upon Francie than upon you. You think of nothing, and care for nothing, except your own concerns. I am disappointed in you. It seems sometimes as if you had no sense of duty. And you ought to leave off giving way to temper as you do. It is so unlike your sisters. Nothing ever seems right with you."

"I can't help it. It isn't my fault."

"Then you ought to help it. You are not a little child any longer."

Mrs. Royston hesitated, as if about to say more; but Magda held up her head with an air of indifference, though invisible tears were scorching the backs of her eyes; and with a sigh she left the room. Magda would let no tear fall. She was angry, as well as unhappy.

Why should she be always the one in disgrace—and never Pen? True, Pen was careful, and neat, and sensible. All through girlhood Pen had been in the right. She had done her lessons, not indeed brilliantly, but with punctuality and exactness. Her hair was always neat; her stockings were always darned; her room was always in order; she never forgot what she undertook to do; she never gave a message upside-down or wrong end before. While Magda—but it is enough to say that in all these items she was the exact reverse of Penrose.

This week she in her turn had charge of the school-room, which was also the play-room. And the result, but for thoughtful Merryl, would have been "confusion worse confounded." Mr. Royston was wont to declare that when his second daughter passed through a room, she left such traces as are commonly left by a tropical cyclone. There was some truth in the remark, if Magda happened to be in a tumultuous mood.

Penrose had her faults, as well as Magda, though somehow she was seldom blamed for them. She had a knack of being always in the right, at least to outward appearance. No doubt her faults were exaggerated by Magda; but they did exist. She wanted the best of everything for herself; she alone must be popular; she could not endure that Magda should do anything better than she did; she was not always strictly true. Magda saw and felt these defects; but nobody else seemed to be aware of them; and she could prove nothing. If she tried, she only managed to get into hot water, while Pen was sure to come off with flying colours.

"And it will be just the same with Patricia Vincent," was the outcome of this soliloquy. "The moment Pen guesses that I like her, she'll step in and oust me. I know she will."

CHAPTER III

ROBERT

WITH a creak, the door was cautiously opened. Somebody put in his head.

"All alone, Magda!"

Depression vanished, and the transformation in Magda's face was like an instantaneous leap from November to June. In a moment her eyes were alight, her limbs alert.

"Rob!" she cried.

"Well, old girl! How are you?"

"You dear old fellow—I am glad."

The new-comer was about her own height, which though fairly tall for a girl could not be so counted for a man. He was slim in make, like Pen; also, like Pen, scrupulously neat in dress. Her eager welcome met with a quiet kiss; after which he seated himself; and his eyes travelled over her, with a rather dubious expression.

"It's awfully jolly to have you here again. You never told us you were coming."

"I happened not to know it myself till this morning. What have you been after?"

"Just now? Playing in the snow."

Rob's gaze reached her shoes, and she laughed.

"Yes, I know! Of course, I ought to have changed them. But it didn't seem worth while. I shall have to dress for dinner soon."

"And, meantime, you are anxious to start early rheumatism!"

"My dear Rob! I never had a twinge of it in my life—I don't know what it means."

"So much the better. It would be more sensible to continue in ignorance."

"Oh, all right. I'll be sensible, and change—presently. I really can't just now. I must have you while I can. When the others know you are here, I shall not have a chance. Are you going to stay?"

"One night. I must be off the first thing to-morrow morning."

"And I've oceans to say! Things that can't by any possibility be written."

"Fire away then. There's no time like the present."

"We shall be interrupted in two minutes. It's always the way! Why do things always go contrary, I wonder? At least, they do with me. If I could only come and live with you, Rob!—now!"

"That is to be your future life—is it?"

"Why, you know! Haven't we always said so? And whenever I am miserable, I always comfort myself by looking forward to a home with you."

"What are you miserable about?"

"All sorts of things. Some days everything goes wrong and I can't get on with people. It's not my fault. They don't understand me."

"I wonder whether you understand them?" murmured Rob.

"And there's nothing in life that's worth doing. Nothing in my life, I mean."

"Or rather—you have not found it yet."

"No, I don't mean that. I mean that there isn't anything. Really and truly!"

Rob said only, "H'm!"

"Yes, I dare say! But just think what I have to do. Tennis and hockey; cycling and walking; mending my clothes and making blouses—not that I'm much good at that! Going to tea with people I don't care a fig for; and having people here that I shouldn't mind never setting eyes on again! Smothering down all I think and feel, because nobody cares. Worrying and being worried, and all to no good. Nothing to show for the half-year that is gone, and nothing to look to in the year that's begun. The months are just simply frittered away, and no human being is the better for my being alive. It's not what I call Life. It is just getting through time. Don't you see? It suits Pen well enough. So long as she gets a decent amount of attention, she's happy. But I'm not made that way; and I can't see what life is given us for, if it means nothing better."

When she stopped, pleased with her own eloquence, Rob merely remarked—

"Don't you think that bit of hard judgment might have been left out? It wasn't a needful peroration."

Magda blushed; and Robert pondered.

"But, Rob—would you like to live such a life?"

Rob's gesture was sufficient answer.

"And yet you think I oughtn't to mind?"

"I beg your pardon. You are wrong to live it."

"But what can I do?"

"Find work. Take care that somebody is the better for your existence."

"I've tried. I can't. It's no good."

"There are always people to be helped—people you can be kind to—people you can cheer up, when they feel dull."

"Pick up old ladies' stitches, I suppose. Interesting!"

"I did not know you wished to be interested. I thought you wanted to be of use."

"Well—of course! But that's so commonplace. I want to do something out of the ordinary beat."

"You want some agreeable duty, manufactured to suit your especial taste!"

"Oh, bother! Somebody is coming. What a plague! And I have heaps more to say. Won't you give me another talk?"

"I'll manage it."

He stood up to greet his mother, as she came in, followed by the two younger girls. The news of his unexpected arrival seemed all at once to pervade the household.

Penrose entered next; and behind her Mr. Royston, a thick-set grey-haired man, of impulsive manners, sometimes more kindly than judicious.

He was devoted to his family; not much given to books; ready to help anybody and everybody who might appeal to him; generally more or less in financial difficulties, partly from his inherited tendency to allow pounds and pence to slide too rapidly through his fingers. A pleasant and genial man, so long as he did not encounter opposition; but it was out of his power to understand why all the world should not agree with himself. His wife gave in to him ninety-nine times in a hundred; and if, the hundredth time, she set her foot down firmly, he gave in to her; for he was a most affectionate husband.

As for his daughters, he doted on them. Steady Penrose, useful Merryl, picturesque little Frip, were everything that he desired. Magda alone puzzled him. He could not make out what she wanted, or why she would not be content to fit in with others, to play games, to sit and work, to do anything or nothing with equal content. Dreams and aspirations, indeed! Nonsense! Humbug! What did girls want with such notions? They had to be good girls, to do as they were told, and to make themselves agreeable. A vexed face annoyed him beyond expression. He could not get over it. He could never ignore it. By his want of tact, though with the kindest intentions, he often managed to put a finishing stroke to Magda's uncomfortable moods.

"Why can't father leave me alone?" she sometimes complained.

Mr. Royston never did leave anybody alone, whether for weal or for woe. Nor did he ever learn wisdom through his own mistakes.

This afternoon, happily, there were no dismal faces. With Rob to the fore, even though he had not fallen in with her views, Magda was in the best of spirits.

She took pains with her toilette that evening—which she was not always at the trouble to do. Sometimes it did not seem "worth while." Yet she well repaid care in that direction. Though not strictly good-looking, she had a nice figure, and knew how to carry herself; and the mass of reddish-gold hair came out well, if properly dressed; and when she smiled and was pleased, her face would hardly have been recognised by one who had seen her only in one of her "November fogs." Rob looked her over, and signified approval by a quiet—"That's right." She expected no more. He never wasted unnecessary words.

Further confidential talk that day proved out of the question, for Rob was very much in request. But Magda waited patiently; for he had promised, and he always kept his promises. Bedtime arrived; and still she felt sure.

"I'm off early," he said, and he looked at her. "Seven-thirty train. Will you be down at seven, and walk to the station with me?"

"This weather!" demurred Mrs. Royston.

"It won't hurt her, mother. She's strong."

"I'm as strong as a horse. Of course it wont hurt me."

"Mayn't we come too?" begged Merryl.

"Only Magda." Rob's tone was final.

"She will never be down in time. Magda is always late," put in Penrose.

Magda's eyes flamed, but she had no need to speak.

"I don't think she will fail me," Rob said tranquilly.

CHAPTER IV

THE INEFFABLE PATRICIA

"THAT'S right," Robert remarked, finding Magda already in the breakfast-room, before a blazing fire. She had on a little round cap and motor-veil, and a heavy ulster lay at hand. "Awful morning. You'll have to let me go alone."

"No, indeed! You said I might."

"Well!" Rob shook his head dubiously. "Got thick boots on? We must hurry. I'm late, though you are not."

Breakfast claimed immediate attention, for only ten minutes remained. On leaving the front door, they found themselves in a smothering hail of small hard snow-pellets, driven by an icy gale, dead ahead. It took all their breath to bore through that opposing blast; and conversation by the way was a thing impossible. One or two gasping remarks were all that could be exchanged.

Umbrellas were out of the question; nor could they get along at the speed they wished. When two white-clad figures at length stumbled upon the platform, Rob's train, though not yet signalled, was three minutes over due.

"I might have missed it!" he said, trying to stamp himself free from a superabundant covering. They took refuge in a sheltered corner beside the closed bookstall, where the wind no longer reached them. "My plan has been a failure. I'm sorry. We must have our talk out next time I come."

"When will you?"

"Ah—that's the question."

Magda spoke abruptly. "Somebody said not long ago that my dream of living with you would never come true, because you were sure to marry."

Robert laughed. "I can't afford it. And my work leaves no leisure. And—I've never seen the girl. Three cogent reasons. So you may pretty well count upon me. I'm a non-marrying man."

Magda's sigh was one of relief. "I'm glad. I don't think I could endure all the home-worries, if I had not that to look forward to. I only wish I could come to you now!"

"Nobody is the worse for waiting. Don't let your life be empty meantime—that's all."

"I've been thinking since yesterday—but really and truly, I can't see what to take up. Father would never let me be trained as a nurse. And I do hate sick-rooms and sick people. And commonplace nursing is such awful drudgery."

"The cure for that is to put one's heart into it. No work is drudgery, if one loves it."

"I should love nursing soldiers in war-time. Or people in some great plague outbreak."

"If you were not trained beforehand, I rather pity the victims of war and plague."

"Of course I should have to learn. But, Rob—you needn't think I mind all drudgery. If I could see any use in hard work, I would work like a horse. But where's the good? Music and French and German are of no earthly use to any one except myself."

"You don't know how soon they may be of use. There are some nice girls who come every week to sing to our hospital patients. Suppose they had never learnt to sing! The other day I came across a poor German sailor, unable to speak a word of English. I would have given much for somebody good at German."

"But to work for years beforehand—just for the chance of things being needed—it seems so vague!"

"That's no matter. Make yourself ready, and there is small fear but that a use will some time be found for you. It is like preparing for an exam—not knowing what questions may be asked, and so having to study a variety of books."

Magda liked the idea, yet persisted—"I don't see, all the same, what I've got to do."

"You have to train yourself—your powers—your whole being—your character—your habits of body and mind. Don't you see? You have to get the upper hand over yourself—not to be a victim to moods—to be ready for whatever by-and-by you may be called to do."

"It isn't so easy!" she said resentfully.

"It's not easy at all. We are not put here to lounge in armchairs and to feel comfortable."

"I sometimes wonder what we are put here for."

"That is easily answered. To do the Will of God, whatever that Will may be. And one part of His loving Will for His children is that they must work—and fight—and conquer."

"If only everything wasn't so abominably humdrum! If there were any sort of a chance of doing anything worth doing!"

"There are hundreds of chances, Magda. They lie all round, in every direction. In ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, when lives are wasted, it is not the opportunity that is wanting, but the will."

"I'm sure I've got the will—if I could see what to do."

As she spoke the train came in. Rob opened a door, put in his bag, and turned for a last word.

"You harp on doing great things," he said. "But the very essence of greatness lies in simple duty and self-sacrifice. It is no question of what you like or don't like, but simply of what God has given you to do. Nothing short of the highest service is worth anything. Don't expect to find things easy. They are not meant to be easy. But we are meant to conquer; and in Christ our Lord, victory is certain. Life is a tremendous gift. See that you use it!"

The train had begun to move. He stepped in and was borne away, waving farewell. She stood motionless, forgetful of the piercing cold. "See that you use it!" rang still in her ears.

But how? Go home to chit-chat, to worries and vexations, to tiresome misunderstandings, to objectless study—which he said ought not to be objectless! Was that using the "tremendous gift" of life?

She was vexed with him for not taking her view of matters, and she was vexed with herself for being vexed; but also she was impressed by what he had said.

"How do you do? So glad to see you!" a pretty voice said. And she turned to meet no less a person than Patricia Vincent, in a fur-lined coat of dark silk, the grey "fox" of its high collar framing her delicate face, with its ivory and rose tinting, its smiling eyes, its fair hair clustering below a dainty fur cap. She might have come out of some old Gainsborough portrait.

"How do you do?" Magda rather shyly responded. Patricia alone had power to make her shy. She felt herself so inferior a creation in that fascinating presence.

"Cold—isn't it? I have been seeing off an old school friend; and she has to go all the way to Scotland. I don't envy her, in such weather. Why did you not come back yesterday? I wanted to see you again."

"I was in such a mess. I couldn't!"

"You had a lovely time in the snow, I dare say. I should have liked it too—only not in my quite new gloves!" The tactful little hint at an apology was perfect. "Is that your brother who is just gone?"

"Yes—Robert."

"I've not seen him before. Somebody was speaking about him yesterday."

"I'm desperately fond of Rob."

Patricia smiled her sympathy. "I'm sure you must be. I could not help noticing you two, though you were much too busy to see me. He looks like—somebody out of the common—if you don't mind my saying so."

"But he is just that. Rob never was the least scrap commonplace. I'm awfully proud of him. And they do like him so much in his parish—everybody does. Have you any brothers or sisters?"

"None at all. And I was left an orphan long ago. So you see I stand alone. Did you know that I had come to stay at Claughton—perhaps for months?"

"No. Oh, I'm glad! Then—I shall see you again!"

The glow of delight was not to be mistaken. Patricia at once recognised a new admirer. She was well used to adulation, and she had plenty, yet never too much, for she could not exist without it; and the earliest token of a fresh worshipper was always hailed with encouragement. Instinctively, she gazed into her companion's eyes, and her soft little hand squeezed Magda's.

"We shall meet very often, I hope. Why not? I think you and I will have to be friends."

"Oh!" Magda cried, breathless. "Oh, I've wanted it so much! I can't tell you how much! Ever since the very first time I saw you, I've longed to have you for a friend. There is nobody else here that I care for—in that way."

"And I have no friends here either. I shall miss all my London friends. But I am quite sure you and I will suit. I always know from the first."

"Oh, and so do I! But you couldn't have thought—yesterday—"

"Yes, I liked you yesterday. I wanted to see you again."

Magda devoured her in response with eager eyes; and Patricia smiled, well-pleased.

"I wonder whether you could come to tea with me to-morrow at four o'clock. My aunt will be out, and we could have a good chat. Can you manage the distance?"

"Oh, quite well. That's nothing. Only five miles. If I can't bicycle, I'll do it by train. There's one that reaches Claughton at ten minutes to four. I shall love to come. How good of you!"

"That will be charming. Now how are you going to get home? Walking! How plucky you are! I wish I could give you a lift, but I have to hurry back; and it is just the other way. So good-bye till to-morrow, Magda. Of course, if it is a 'blizzard,' I shall not expect you."

Magda privately resolved that, blizzard or no blizzard, she would not be deterred. She watched the brougham out of sight, then hurried home with the wind in her back, helping now instead of hindering. She trod upon air, so great was her exultation.

That Patricia should want her for a friend! Patricia, of all people! It was sublime! The impression made by Rob's words sank for a time into the background of her mind. She could think of nothing but this new delight.

After all—life was worth living—with such a prospect!

CHAPTER V

UNWELCOME NEWS

MAGDA, having removed her snowy garments, found the family round the breakfast-table; and she did not disdain a second course of tea and toast after her early outing.

She certainly looked no worse for the walk. Her face glowed with delight.

"Letters—letters!" quoth Merryl, next in age to Magda, and a complete child still, despite her fifteen years—plump and rosy, unformed in feature, but with a look of beaming good-nature and pure happiness, which must have transformed the plainest face into pleasantness. She was busily engaged in buttering her father's toast. From early infancy she had been his especial pet; and her seat was always by his side. Mr. Royston without Merryl was like a ship without its rudder—a helpless object.

"Lots of letters for everybody except Magda," piped Francie's small treble.

"So much the better for me! I haven't the bother of answering them," Magda said joyously.

"Seem to have liked your walk," Mr. Royston remarked in puzzled accents. For Magda, after parting with Rob, was usually what he described as "in the dumps" for hours.

"I just love a fight with the snow. And I've seen Patricia Vincent. She was at the station too. And she has asked me to tea to-morrow."

There was a note of triumph in the tone, for Magda was aware that Pen had been counting on some such invitation for herself.

"How did you manage to bring that about?" asked Pen, obviously not pleased.

"I didn't manage at all. She simply asked me."

"You must have said something. It is not the Claughton Manor way to invite people informally."

"I suppose it's her way. Now she has come to live there—"

"She has not."

"Well, anyhow, to stay for a long while—"

Penrose demurred again, and Mrs. Royston put in a word.

"Yes, dear. Mrs. Framley told me, and I forgot to mention it. Miss Vincent has lived for years with some London cousins; but the eldest daughter was lately married; and things now are not so comfortable. I fancy she and the second daughter do not much care for one another. And Mr. and Mrs. Framley have proposed that she should make the Manor her headquarters. The plan is to be tried."

"She has plenty of money. Why doesn't she live in a house of her own?"

"Too young, Pen. She is only twenty-two."

"She is the very sweetest—" began Magda rapturously, and checked herself at the sound of Pen's little laugh. Magda crimsoned.

"Heigh-ho! What's wrong now?" Mr. Royston stopped in the act of turning his newspaper inside-out, and fixed inquiring eyes upon his second daughter.

"Pen is so disagreeable."

"Come, come! You needn't complain of other people. Pen is a good girl—always was! I wish other girls were as good."

Pen wore an air of pretty and appropriate meekness.

"I know! I'm always the one in the wrong."

"Then, if I were you, I wouldn't be—that's all. I would take care to be in the right."

Mrs. Royston wisely rose, and a general move followed. Magda fled upstairs, only to find her room in process of being "done;" so she caught up a rough-coat and a tam-o'-shanter, and escaped into the garden. Already the snow had ceased to fall, and the sky was clearing.

To and fro on a white carpet in the kitchen garden she paced, pitying herself at first for home grievances, but turning soon to the thought of Patricia, going over the past interview, seeing again the dainty flower-like face, hearing afresh the pretty voice, picturing the joys of coming intimacy.

Now at last she would have a real friend, the sort of friend she had always wanted, a satisfying friend, one who would meet her needs, one who would understand her feelings, one who would enter into her dreams and aspirations, one to whom she could look up with unbounded admiration—different altogether from good little Beatrice Major, who was well enough in her way, but totally unlike this!

That word—"aspirations"—pulled up the recollection of Rob and of all that he had said. She was to begin at once to make ready for her future life with him.

Yes, of course; and she meant to do it. She was not going to "drift" any longer. She would hunt out her neglected plan of study, and would start with it afresh. That was all right. If once she really made up her mind, of course she would do it. She was not one of those weak creatures who could not carry out a resolution.

Only—not this morning. There was so much to think about!—and Pen was so annoying!—and she felt so unsettled! To seat herself down to a French translation or a German exercise in her present condition was impossible.

"You've got to get the upper hand over yourself. Not to be a victim to moods!" So Rob had said.

Oh, bother! what did Rob know about moods? He never had any. He was always the same—always calm and composed and steady; the dearest old fellow, but without a notion of what it meant to be made up of all sorts of opposite characteristics, and never in the same state for two consecutive quarters of an hour. People could not help being what they were made! She meant to get the upper hand of herself—in time. But it was absurd to expect impossibilities.

So the hours drifted by; and another day was added to the waste pile.

After the next night came a rapid thaw. The world around streamed with water, while a wet fog hung overhead. It made no difference to Magda. Go she would, no matter what the elements might say.

Mrs. Royston tried remonstrance, but Magda's agony at the notion of giving up was too patent, and she desisted. Bicycling was out of the question; so the train had to be resorted to and twenty minutes' walk through the soaking grounds brought her to the Manor with boots clogged in mud.

What did that matter? After an abnormal amount of boot-rubbing, she was shown upstairs into Patricia's special sanctum, a "study in blue," as she was presently informed, carpet, curtains, cretonne covers, all partaking of the same hue. Patricia, also in blue, welcomed her sweetly, exclaimed at her condition, set her down before the fire to dry, gave her tea, and gradually unlocked a tongue, which at first seemed tied.

However, once it was untied, the young hostess had no further trouble. Magda could talk; none faster! She poured out the contents of her mind for Patricia's inspection; and Patricia listened, with always those sweetly smiling eyes, and little pearly teeth just showing themselves. Once or twice a close observer might have detected a puzzled look at some of Magda's flights; but she was invariably sympathetic—or she seemed so, which did as well under the circumstances.

Magda was used to sympathy from Bee, though hardly of the same kind. Bee would sometimes differ from Magda; never otherwise than gently, yet with decision. Patricia disagreed with nothing. She had that captivating habit, possessed by some agreeable people, of managing always to say exactly what her listener would have wished to hear. Though not by birth Irish, she really might have been so; for this is one of the Green Isle's characteristics.

So, whatever Magda chose to utter, she found herself in the right; and if aught had been needed to complete the enchaining process, this was sufficient. When she went home that afternoon, she was wildly happy. In Patricia she had found an ideal friend; the dearest, the sweetest, the loveliest, ever seen. She had now all she wanted!

The fascination grew. Magda never did anything by halves; and during the next few weeks she had eyes, ears, thoughts, for Patricia only. When they parted, she could not be content unless the time and place of their next meeting were named. If she could not see her idol for two or three days, she sent rapturous notes by post. Every spare shilling of her pocket-money went in gifts for Patricia. Half her time was spent upon the road between Burwood and Claughton.

"It is getting to be a perfect craze," Mrs. Royston one day remarked to Penrose. "I really don't know what to do. The Framleys will be bored to death, if it goes on."

"Patricia herself is having rather too much of it, I suspect. I noticed her face yesterday afternoon when Magda was hanging round and would not leave her for a moment. Naturally she wanted to be free for other people."

"I thought she was affectionate to Magda. Still, the thing may go too far. Magda has no balance. Some day I shall have to give her a word of warning."

"I would, mother!"

But Mrs. Royston delayed. Magda seemed aboundingly happy; and she rather shrank from putting a spoke in the wheel. Matters might right themselves.

One morning, after an especially rapturous afternoon of intercourse with Patricia, Magda found on the breakfast-table a letter from Bee. She had not given much thought to Bee lately—had not written to her for weeks. She felt a little ashamed, and began to read under a sense of compunction.

Then a startled—"Oh!"—all but escaped her.

"Anything wrong?" asked Pen.

"Why should anything be wrong?"

"You looked the reverse of pleased."

Magda retreated into herself, and refused to discuss the question. Breakfast ended, she escaped to her favourite quarter, the kitchen garden, now a blaze of spring sunshine, and there she went through the letter a second time.

"Bother! I hoped that was all given up!" she sighed.

"Think, how lovely!" wrote Bee in her pretty ladylike hand. "We really are coming to Burwood. Do you remember my telling you that it was spoken about? My mother heard of a little house which she went to see; and she liked it so much that she made up her mind quickly. She did not tell me this till I got home; and there were one or two hitches, so I would not say any more to you till everything was arranged."

"Now papers are all signed, and the house will be ours in the end of June. It has to be painted and papered, and I suppose we shall not get in before August. It is near the Post Office in High Street—standing back in a little garden—and it is all grown over with Virginia creeper—so pretty, mother says. It is called 'Virginia Villa.'"

"I cannot hope that you will be as glad as I am; still I do feel sure that it will be a pleasure to my darling Magda to have her 'little Bee' within such easy reach. Only think of it! I often sit and dream of what it will be to have you always in and out—every day, I hope, and as often in the day as you can manage it. You will know that you cannot come too often."

"I'm hoping for a most lovely treat this summer. Isn't it sweet of Amy? She has been saving and laying by money all the last year, and now she is bent on taking me to Switzerland for three weeks in July. I can hardly believe it to be true. I've always had such a longing for Swiss mountains!"

"To-morrow I am going into the country for three weeks with Aunt Belle and Aunt Emma—mother's sisters, you know. If you should write to me then, please address—'Wratt-Wrothesley, —shire.' I am longing to hear from you again."

Magda was half touched, half aggrieved. She hardly knew how to take it. She and Beatrice had been friends through two long years of school-life; and though she might make little of the tie to Miss Mordaunt, it had been a close one. Bee had loved her devotedly; and she had been really fond of Bee. Yet, somehow, she did not take to the idea of having Bee permanently in Burwood, for reasons earlier explained.

Things looked even worse to her now than when she was at school. Her mother and Pen were so awfully critical and particular. She minded Pen's little laugh of disdain almost more than she minded anything. It would be horrid if that laugh were called forth by a friend of hers.

And then the small creeper-grown house in High Street, where till now a successful dressmaker had lived—it really was too dreadful! To think of her especial friend living there—in Virginia Villa! She was certain that nothing would ever induce her mother to leave a card at that door. And if not—if Mrs. Royston declined to call—it would be quite as objectionable. To have a friend in a different stratum, so to speak, just allowed in their house on occasions, just tolerated perhaps, but looked upon as belonging to a lower level—how unbearable! And Bee's relatives might be—well, anything! They might tread upon the sensitive toes of her people at every turn. If only Bee had never thought of the plan!

Worse still—much worse!—there was this delightful new friendship with Patricia Vincent. Most certainly neither Patricia nor her aunt, Mrs. Framley, would deign to look at any human being who should live in Virginia Villa. To them it would be an impossible locality. For a dressmaker, well enough—and nothing would exceed their gracious kindness to the said dressmaker. But—for a friend! Magda went hot and cold by turns. She had not haunted Patricia for weeks, without becoming pretty well acquainted with the Framley scales of measurement.

When the Majors should have settled in, she would have to keep her two friends absolutely apart—to segregate them in water-tight compartments, so to speak. But would this be possible? Suppose, some day, they should come together! Suppose that Patricia should find her chosen friend's other friend to be a mere nobody, living in that wretched little house! Why, it might squash altogether this new glorious friendship of hers!

And the more she considered, the more certain she felt that the two must sooner or later meet. Burwood was not a large town. Everybody there knew all about everybody else. To be sure, the Framleys lived apart, and held themselves very much aloof from the townsfolk generally. Still, accidental encounters do take place, even under such conditions, just when least desired.

And Bee was so simple; she would never understand. Nobody could call so gentle a creature "pushing;" but on the other hand it would never occur to her mind that anybody could object to know her, merely because she lived in an insignificant house. She had a pretty natural way of always expecting to find herself welcome. Magda had heard that way admired; but she felt at this moment that she could have dispensed with it.

She would have to make Bee understand—somehow. She would have to explain that not all her friends and acquaintances would be likely to call—in fact, that probably very few would. It would be very difficult and horrid; but since the Majors chose to come, they must take the consequences.

Always in and out! That was very fine; but neither her mother nor Pen would stand such a state of things—considering the position of Virginia Villa. Magda had a good deal of liberty, within limits; but those limits were clearly defined.

In this direction she did not want more liberty. She could not be perpetually going after Bee. Her time was already full—of Patricia.

True, Bee was the old friend, Patricia was the new. But she had always felt that Bee could not fully meet her needs, and Patricia could—which made all the difference. Patricia was more to her—oh, miles more!—than poor little Bee.

As she felt her way through this maze of difficulties, a thought suggested itself. Why need she say anything at present about the coming of the Majors to Burwood?

Nobody in the place knew them. It was nobody's business except her own. There was plenty of time. They would not arrive for weeks and weeks. And each week was of importance to her for the further cementing of her new friendship. She could at least—wait.

By-and-by, of course, it must be told; and her mother must be asked to call; and Pen's little laugh of disdain must be endured. But there was no hurry. For a while longer she might allow herself to revel in the Patricia sunshine, without fear of a rising cloud.

CHAPTER VI

SWISS ENCOUNTERS

TWO girls sat in a tiny verandah, outside the third storey of a Swiss hotel, facing a horseshoe group of dazzling peaks. Or rather, one of the two faced it, while the other faced her.

She who gazed upon the mountains, a slender maiden, pale, with brown eyes and wavy hair and rather heavy dark brows, did nothing else. It was enough to be there, enough to look, enough to study and absorb Nature's glories.

But the second—a girl only by courtesy, being many years the older—a short plump vigorous person, snub-nosed, with insignificant light eyes and tow-coloured hair—seemed to find an occasional glance at lofty peaks sufficient. For each glance sent in that direction, half-a-dozen glances went towards her companion; and in addition, she busily darned a dilapidated stocking.

Despite the difference in age, a difference amounting to over twelve years, those two were intimate friends. Yet it was a friendship of sorts; not alike on both sides. The younger girl's love for her senior was gentle and sincere. The elder's love for her junior amounted to an absorbing passion. Amy Smith would have done anything, given anything, endured anything, for the sake of Beatrice Major.

"Amy—if you could only know what a delight this trip has been to me!—has been and is!"

"My dear, one couldn't watch your face and not know."

"But to think that it is all you!—that you have saved and scraped and denied yourself—and just for my sake! And I never dreaming all those months, when you said you could not afford this and that and the other—never dreaming what you had in your mind!"

"It has been one long joy to me. You wouldn't wish to deprive me of it."

"But that you should have given up so much—for me!"

"Nobody minds giving up a shilling for the sake of a guinea."

"If I could feel that I deserved it—but I don't."

"I know, my dear!"

"You don't—and I can't make you."

She looked up to meet the steadfast gaze; a gaze which she understood. It meant that if Amy had her, there was no need for aught beside. And she could not return this devotion in kind or in degree. She did want something else.

"C'est toujours l'un qui aime, et l'autre qui se laisse aimé." Was it always so? Not altogether; for she did love dear kind Amy, truly and faithfully. But with the same love!—ah, no. And this seemed cruel for Amy.

"How I shall miss you in Burwood!" she said, with an earnest wish to give pleasure. And, indeed, it was true! She could not but miss the constant outpouring of affection which she had had from childhood, even though at times she might have felt its expression a trifle burdensome. But she would not miss as she would be missed.

"Will you—really?" Amy was generally blunt in speech and manner; yet she could be wistful. The plump plain face softened; the little snub nose flushed with the flushing of her freckled brow and tanned cheeks; and the pale grey eyes grew moist. "Bee—will you want me?"

"Of course I shall, at every turn. Think how long I have had you always."

"You will have Magda Royston now."

"Yes." Bee forgot to say more. She looked away at the lofty peaks opposite, where a ruby gleam lay athwart the snows. Yes, she would have Magda. She remembered in a flash her letter to Magda, telling her so eagerly of the settled plans; and her own hurt feeling at receiving no response.

In a month the response came; but before the close of that month another personality had entered her life. The three weeks at "Aunt Belle's" meant much to her. She had been in close touch with one whom she could never forget, who could never in the future be to her as a stranger. An impress had been made upon her life, transforming her at one touch into a woman. And if her love for Amy had paled a little before her warmer love for Magda, as starlight pales before moonlight, her love for Magda paled before this fresh experience, as moonlight pales before sunlight. Not that in either case her affection actually waned or altered, but that the lesser light became of necessity dim by comparison with the greater.

Nobody knew or suspected what had happened. Her gentle self-control prevented any betrayal of feeling on her part. The two had indeed been a great deal together, during those three weeks, but intercourse came about so simply and naturally, that she never could decide how far it was purely accidental, how far as a result of effort on his part. He seemed to enjoy being with her; and they seemed to suit; but whether he would remember her, whether he had any strong desire to meet her again, were questions which she had no power to decide. Their paths might lie permanently apart.

When the expected letter at last came from Magda, though she was a little grieved at the manifest lack of real delight in the prospect of having her at Burwood, it could not mean the same that it would have meant before that visit. For one who has been in strong sunshine, the brightest moonlight must seem pale.

"Bee, what are you cogitating about? I don't understand your face."

Bee smiled. "I was thinking over—varieties. These mountains make one think. Yes, I shall have Magda. But one friend does not fill another's place. You will always be you to me."

"And she will be she, I suppose."

"Yes; but she can never be you. Don't you see?"

Amy sighed profoundly. "All I know is that London will be a desert without you. And I'm torn in half—do you know that sensation?—between two longings. I long for you to be happy in Burwood; and if you weren't happy, I should be miserable. And yet I long for you to miss me so desperately that you can't be happy without me. There!—it's out! Horrid and mean of me! But it's true."

"Amy, you never could be mean. You are only too good—too unselfish."

"It's all selfishness. You don't understand. I love doing anything in the world for you, purely as a matter of self-gratification. Real unselfishness would only want you to be perfectly happy—apart from myself. And what I do want is that I should make you happy. Which means that, if I can't, I'd rather nobody else should. Isn't it disgusting?"

"But you have made me happy. I can't tell you half or a quarter of the joy this trip has been to me. I have so longed all my life to see Swiss mountains. And you have given me the joy! I do believe there is going to be an afterglow, and we shall miss it! Just time for table d'hôte."

Once before the glow had occurred when they were all engaged in what Amy disdainfully described as "gormandizing."

"We've got to be in bed early to-night, mind, Bee. I want you to get well rested for to-morrow's exertions. Sure you are fit for it?"

"I never was more fit in my life. It will be splendid."

"And to-morrow night we sleep at the Hut."

"Delightful! Such an experience! I don't believe I shall sleep a wink to-night, thinking about all we are going to see."

"You must, or you won't be up to the walking."

After two weeks of lesser practice, and divers small climbs, they were going on a real expedition—their first ascent, worthy of the name—under charge of Peter Steimathen, than whom they could have found no more dependable guide, and his son, Abraham. Both girls were of slight physique; both were by nature sure of foot; and both dearly loved climbing. Since both were Londoners, their opportunities hitherto had not been great in that line; but they had taken to it like ducklings to water. Peter Steimathen, after some consultation, pronounced that they might safely, under his guidance, make the attempt.

At table d'hôte Beatrice found a stranger by her side; a reticent young English clergyman, slim in make, with quiet observant eyes. She had never met him before; yet something once and again in his look seemed familiar, and she vainly tried to "locate" the resemblance. He and she fell easily into talk—strictly on the surface of things.

"Yes, we are going for a climb to-morrow," she said soon. "Nothing big, of course. We are only beginners. It is called the Rothstock—a lesser peak of the Blümlisalp group."

"You will want a guide for that, if you are beginners."

"We would not venture without Peter Steimathen."

"I know him. You couldn't do better."

"Are you going up somewhere too?"

"The Blümlisalphorn."

"Not alone! You have a guide."

"No, I have a friend. Not here—he has a room in a châlet close by. We are both well used to the mountains. No need for a guide."

"People say that is not safe."

"Depends!" And he smiled. "We've done a good deal together that way."

"Without guides?"

"Without guides."

"I hope you won't come to grief some day."

"I hope not!"

"You think it is wise?" dubiously.

"Extremely wise. But you must be careful—excuse me! There are traps for beginners that don't affect old hands."

"Peter Steimathen!" she suggested.

"He is excellent. But you must do as he tells you."

"Oh, I've learnt to obey," laughed Bee.

Then she saw that his attention was distracted; and her own became distracted also. Two new arrivals had just come in; a middle-aged lady, stout and handsomely dressed; and a girl, young, and quite lovely. She had one of those picture-faces which are seen two or three times in a half-century. Not Bee's gaze alone suffered distraction. The whole room gazed; and the object of all this attention received it calmly, without a change of colour or the flicker of an eyelid.

"She's used to it," Bee remarked to herself.

But it was impossible not to go on gazing. The face was one that nobody could glance at once and not glance again. Soft curly fair hair clustered about a fair brow; and the delicately tinted complexion made one think of snowflakes and rose-buds, or of early dawn in June. A slender figure, full of grace, shell-white arms and hands, features pretty enough not to detract from the exquisite colouring, helped to make up the tout-ensemble; and the forget-me-not blue eyes smiled graciously at the elder lady, at the waiters, at the table-cloth, at anything and everything that they happened to encounter.

Beatrice cast an involuntary side-glance towards her neighbour. He too was gazing; and in the quiet eyes she detected a subdued intensity, of which she would not have thought them capable.

"Isn't she sweet?" breathed Bee.

The remark was not even heard, and no reply came. Their broken talk was not renewed; and he disposed of eatables with the air of one who hardly knew what was before him. Dinner ended, the vision disappeared, and so did Bee's neighbour; but an hour later she was amused to see him at the further end of the saloon, in close talk with the pretty new arrival.

Meeting him still later in a passage, she paused and made some slight reference to the girl.

"I wonder who she is," Bee said.

"A friend of my sister's," he replied. "Singular, our meeting here. I have heard of her before."

Bee noted again a suppressed gleam in his eyes.

CHAPTER VII

A MOUNTAIN HUT BY NIGHT

THE Frauenbahn Hut, at last!

For eight hours and a half, including rests, they had been en route, with their guide and porter, making the steep ascent from Kandersteg, winding through pine-woods, pausing at the rough Oeschinen Hotel, skirting the deep-grey waters of the lake from which it took its name—then mounting again to the "Upper Alp," only to leave that also behind, as they yet more steeply zig-zagged onward over rough shale, with the glacier to their right and the Hut for their aim.

An experienced mountaineer would have covered in six hours the distance they had come; but, naturally, it took them a good deal longer, which meant arriving late.

Both were very tired and very happy, and in a state of mental exhilaration, which, despite fatigue, gave small promise of getting quickly to sleep amid such unwonted surroundings. Thus far, though the way had been steep, they had had a rugged path. On the morrow they would quit beaten tracks, and would do a "bit of the real thing," as Amy expressed it.

The guide, Peter Steimathen, had proved himself a pleasant companion all that day. Fortunately, since neither of the two was a practised German speaker, he had some command of English.

A rough little place was this Frauenbahn Hut, though better than most mountain refuges, for, in addition to the room on the ground-floor, it boasted a loft above, both being on occasions crammed with climbers. Nearly half the lower room consisted of a shelf, some three feet from the floor, covered with a bedding of straw; and on this the girls would spend their night, rolled up in rugs, provided for sleepers. High above their heads the guides would repose on another shelf, to reach which some agility was needed.

Beatrice and Amy counted themselves fortunate in finding the Hut empty. Apparently they would have the place to themselves. They looked round with interest at the wooden walls, the small window, and the stove at which the guide was preparing to boil water for their soup.

"But come—come outside," urged Amy. "Don't let us miss the sunset. It won't wait our pleasure. We can examine things inside by-and-by. Come!"

And they went, commandeering hut rugs for wraps, since it was "a nipping and an eager air" here, nine thousand feet above the sea-level.

"To think of it! Up in the very midst of the mountain amphitheatre!" murmured Amy.

When seated side by side on the bench, silence fell. They had chatted much in the early stage of their ascent; or rather, Amy had chatted and Bee had listened, which was a not unusual division of labour between them. Bee was a good listener. But more than once Amy had detected a wandering of attention, which was not common. At least, it had not been common till lately.

"Dreaming, Bee?" she had asked; and Bee blushed. Amy noted the blush, putting that down also as something new.

But Amy too for once became dumb, as they gazed from their Alpine Hut over the wide snowy expanse. It was hardly a scene to induce light chatter.

The track by which they had mounted from the Oeschinensee was already lost in darkness. But in front stood forth the roseate peaks of the Blümlisalp; notably the Weisse Frau, square-shouldered, and clothed in a mantle of ineffably delicate pink; and beyond her, almost bending over her like a devoted bridegroom, stood the yet loftier Blümlisalphorn, scarcely less pure, though broken by lines and ridges of rock which lay at too sharp an angle to retain snow. Nearer was the bare and rocky Blümlisalp-stock, cold and grim in the twilight, rising abruptly from the névé of the glacier.

Long lingered the mysterious radiance of the afterglow on the spurs and slopes of those great Gothic peaks, until the last filmy veil, sea-green in hue, faded before the onslaught of night. Then attendant stars began to twinkle in the vault over the Blümlisalphorn, forming a little crown above his head.

The two girls held their breath, clasping hands under the rugs.