The Mighty Deep: And What We Know of It

Agnes Giberne

Transcriber's Note

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

THE MIGHTY DEEP

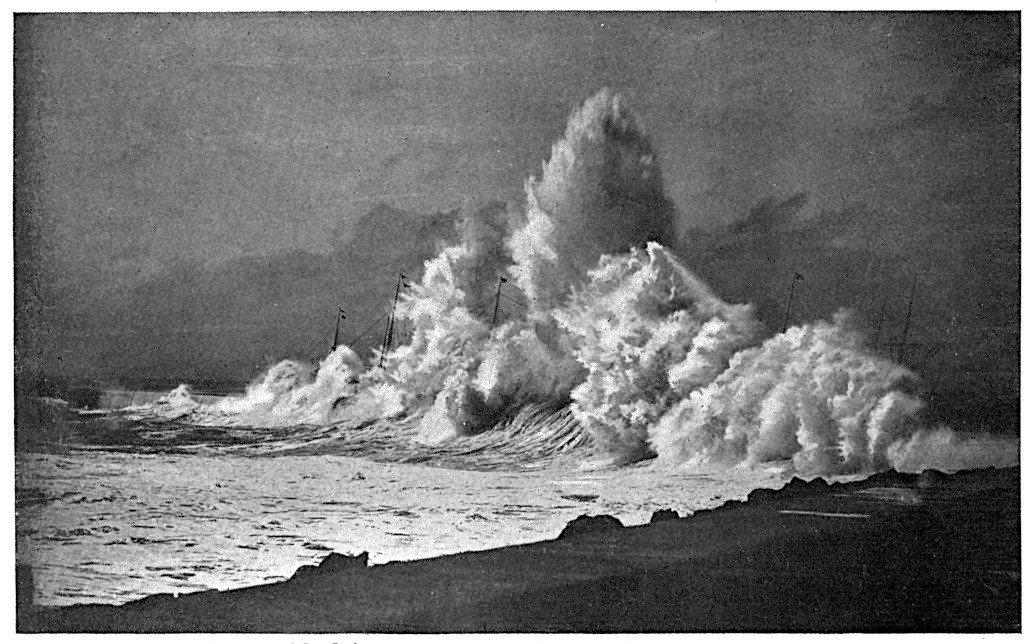

By permission of the Apothecaries’ Co., Ceylon

BURST OF THE SOUTH-WEST MONSOON AGAINST THE COLOMBO BREAKWATER

Frontispiece

THE MIGHTY DEEP

AND WHAT WE KNOW OF IT

BY

AGNES GIBERNE

AUTHOR OF “SUN, MOON, AND STARS”; “RADIANT SUNS”; “ROY, A TALE OF THE DAYS OF SIR JOHN MOORE”; ETC., ETC.

“If I had asked thee, saying, How many dwellings are there in the heart of the Sea? ... peradventure thou wouldst say unto me, I never went down into the Deep.”

2 Esdras iv. 7.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

London

C. Arthur Pearson Ltd.

Henrietta Street

1902

DEDICATED

TO THE REVERED MEMORY OF

VICTORIA THE GREAT, R.I.

SOVEREIGN LADY OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE

QUEEN OF THE OCEAN

AND

MOTHER OF HER PEOPLE

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

ROY

A STORY OF THE PENINSULAR WAR

Crown 8vo, cloth, with illustrations, price 5s.

PRESS NOTICES

“An interesting and well-studied romance of military adventure.”—Scotsman.

“The illustrations are good, the writing is pithy, and the tone well calculated to inspire youthful readers with lofty ambitions.”—Morning Advertiser.

London: C. ARTHUR PEARSON, Limited

HENRIETTA STREET, W.C.

PREFACE

This little book makes no profession to be a systematic text-book of Oceanography, or to contain exhaustive discussions of the latest discoveries and theories. The subject is far too vast to be so dealt with in one small volume. A library would almost be needed for the purpose.

Much information has been gained within the last decade or two of years about the Ocean, its make, the laws which govern its movements, its dark and mysterious depths, the various deposits upon its bed, and the innumerable living creatures by which it is inhabited. All that I have attempted has been to cull a certain number of leading facts from the great storehouse of knowledge, and to put them in order, for the many who love sea-breezes and ocean-waves, and who may like to know a little more about the friend whom they so often visit.

With regard to Authorities, I must acknowledge my indebtedness to the following books, among many others: The Realm of Nature, by Dr. H. R. Mill; Report of the Scientific Results of the Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger—Deep Sea; Coral Reefs, by Professor Dana; Standard Natural History, edited by J. S. Kingsley; The Microscope, by Carpenter, revised edition; British Merchant Service, by R. J. Cornwall-Jones; Resources of the Sea, by McIntosh; Harvest of the Sea, by J. G. Bertram; also numerous papers and articles in the Geographical Magazine, National Geographical Magazine, Scottish Geographical Magazine, Proceedings of Royal Society of Edinburgh, Annual Report of Smithsonian Institution, Natural Science, etc., etc., by such writers as Sir John Murray, Dr. H. R. Mill, Professor James Geikie, Albert Prince of Monaco, Admiral Sir W. H. L. Wharton, Mr. John Milne, Mr. A. Günther, Mr. John Aitkin, etc.

In conclusion, I beg heartily to thank the Librarians of the Royal Geographical Society and the Zoological Society of London for the generous courtesy with which they have lent me books and supplied latest information, without which this little book could never have been written; also to express my warm gratitude for the invaluable help afforded by the criticisms and suggestions of the kind and able friends who have read my MS. and proofs.

Worton House, Eastbourne.

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | “The Sea! the Open Sea!” | 1 |

| II. | Salt Water | 10 |

| III. | Earth’s Vast Ocean | 19 |

| IV. | Subject to Law | 27 |

| V. | In Ocean Depths | 37 |

| VI. | Rivers in the Sea | 50 |

| VII. | Of Wind and Water | 61 |

| VIII. | An Ocean of Azure | 70 |

| IX. | Ice-Needles to Ice-Mountains | 79 |

| X. | Receiving—to Give Again | 89 |

| XI. | A Story of Conflict | 102 |

| XII. | About the Long Past | 110 |

| XIII. | Old Ocean as a Builder | 122 |

| XIV. | How Chalk is Made | 135 |

| XV. | Of Ocean-weeds | 149 |

| XVI. | Coral Architects | 163 |

| XVII. | Over the Ocean-bed | 176 |

| XVIII. | Multitudinous Life | 185 |

| XIX. | Ocean Flowers and Lamps | 196 |

| XX. | Armoured Myriads and Monsters | 207 |

| XXI. | A Goodly Company of Crabs | 220 |

| XXII. | The World of Fishes | 230 |

| XXIII. | Some Oddities of Fish-life | 241 |

| XXIV. | Behemoths of the Ocean | 252 |

| XXV. | “Down to the Sea in Ships” | 261 |

| XXVI. | An Empire: Ocean-wide | 276 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| The burst of the South-west Monsoon against the Colombo Breakwater | Frontispiece |

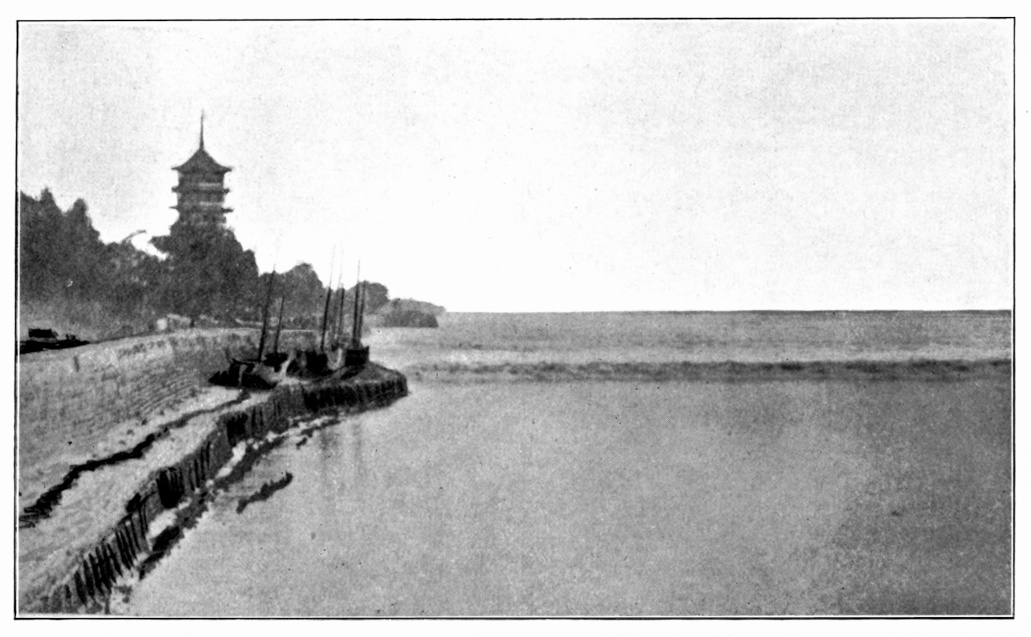

| Bore of the Tsien Tang Kiang | Facing page34 |

| An Iceberg, showing the section under water | ”86 |

| Diatom Cases | ”154 |

| Part of Diatom Case | ”156 |

| Deep-sea Fishes | ”182 |

| Beam-trawl and Tow-net employed in deep-sea research | ”188 |

| A Deep-sea Crab | ”220 |

| A Blue Whale | ”254 |

THE MIGHTY DEEP

CHAPTER I.

“THE SEA! THE OPEN SEA!”

“Therefore also do men entrust their lives to a little piece of wood.”

Wisd. of Sol. xiv. 5.

ONCE upon a time, over two thousand years ago, our ancestors lived in a country smaller than ours, to the north-east.

They had not yet taken possession of two Isles, which in the then distant future were to become the Headquarters of a world-wide Empire. Already one characteristic of the race was prominent; they delighted in the Sea. Within their small limits of power they ranged the Ocean, they wrestled with its fury, they subdued it to their will, they rejoiced in its strength, they found often their graves beneath its surface. The English then, as now, were Ocean-folk.

May it not be that we in modern days love the sea, and flock to its shores, and carry our Flag to its furthest bounds, because our forefathers, the Norsemen, the Angles, the ancient Vikings, found their joy in it? Their march, like ours, was on the mountain-wave; their Home, like ours, was on the deep.

Probably with them, as with us, it was not always an unchastened joy. Even a hardy Viking might know the unpleasant consequences of Ocean’s rougher moods. But no such discomforts drove him to stay ashore.

Had our forefathers been made of feebler stuff, had they been easily checked in their enterprises, centuries of history must have been changed. The development of English nature would have followed other lines.

In those days the fight could not but be severe. No mighty ironclads, no huge three-deckers, existed. No P. and O. liners, no great merchant ships ranged the seas. Our forefathers tackled the waste of waters with what we should consider the merest cockleshells. Even in these days we know what is meant by “perils of the seas;” but in those days the term must have carried a hundred-fold deeper meaning, both to the brave fellows who ventured on the stormy main, and to the waiting wives and mothers on land.

All the more honour to them that they were not daunted. Each man’s victory or failure in life’s battle cannot but help to shape the course which his descendants in future ages will pursue.

The Sea for us has a vivid personality. We know grand old Neptune so well, with his trident and his snowy hair, his dashing waves and his impenetrable depths, his gentle breezes and his furious gales, his moods of mild serenity and his fits of vehement wrath. He has his faults; but in spite of all we love him.

At one time the Sea was for men a type of the Infinite, of the Immeasurable, of the Boundless. We use still the same words; but they have lost some of their force.

In these days the whole ocean has been mapped out from shore to shore. We know exactly what countries lie round each part of it. We can tell how long and how wide it is in any direction. As we stand on the shore, and talk of the “boundless ocean,” we are perfectly well aware that we are looking across to France or Spain, to Germany or Ireland or America. Grand and far-reaching the sea still is, but to us no longer “boundless.”

In ages gone by, those who stood upon the coasts of Palestine or Egypt, of Greece or Italy, gazed towards unknown horizons, across what was to them an illimitable ocean. The civilised world consisted of a few countries bordering the Mediterranean on the east; and those countries shaded off into unexplored barbaric regions. As for the “great Sea,” as they called that which we regard as hardly more than a huge inland lake, it was in their eyes the embodiment of Infinitude.

At a very early period, long before the English Nation was dreamt of, before the Roman Empire had grown into being, while the polished Greek of the future was still a semi-savage, a nation of Ocean-lovers already existed. These were the Phenicians, foreshadowing in their pluck and enterprise the sea-going British of later times.

They, unlike the sailors of other nations, did not merely hug the shore, but ventured out into the trackless ocean. They, unlike the sailors of other nations, did not go upon the sea only in daylight, but they traversed it also in the dark hours of night.

At first they were content with the nearer reaches of the Indian Ocean, and with the more eastern parts of the Mediterranean. But gradually they wandered farther. Colony after colony was planted beyond Egypt, till they reached the Pillars of Hercules, known to us as the Straits of Gibraltar, to face a wild and strange Ocean, full of mystery.

There they made a startling discovery, enough to impress the more thoughtful minds among them. Far to the east, in the “Indian Ocean” of our days, their sailors had been acquainted with high and low tides; while throughout the Mediterranean scarcely any tides existed. But in the open sea, outside the narrow Channel, they found the very same tidal changes as in the eastern ocean.

It is hardly to be supposed that any one of them had a mind of such far-seeing grasp that he should be able to conjecture the grand truth of eastern and western oceans being ONE—swayed by the same influences, governed by the same laws.

A Phenician of those days, catching a glimpse of this truth, would have been worthy to take rank beside our Sir Isaac Newton of after days. They are believed to have observed the coincidence; no doubt with a feeling of wonder; and probably it was to them merely a coincidence. Very little was then understood of the most everyday and commonplace workings of Nature.

Not much, indeed, can be said with certainty of what the Phenicians did truly discover. Some observations they must have made of the heavenly constellations; and the Pole-star at least must have been known to them, otherwise it is impossible to imagine how they could have steered their vessels at night, in an age when the Mariner’s Compass was unknown. They are supposed to have sailed far south on the west coast of Africa, if they did not actually round the Cape of Good Hope.

It does not appear that their knowledge was passed on to the Greek nation. Either they were curiously reticent of what they knew, or else such records as they may have left were destroyed and forgotten.

In after times the Carthaginians, descendants of Phenician Colonists, were, like their forefathers, sea-lovers, sea-explorers, searching the main, not as travellers search now from pure love of knowledge, or from a liking for adventure, but for the sake of commerce. The Carthaginians, however, instead of being able to make use of previous discoveries, and to work onwards from a point already gained, had to start afresh and to find their way—just as if it had never been found before—to and beyond the Pillars of Hercules.

To the Greek imagination that wide mysterious Ocean, opening out from the narrow Strait, was unattractive and terrible. It was a sea of limitless distances, of fog and gloom, of blackness and death; not an unexplored Ocean of possible glory and beauty and wealth.

Time glided by, and man advanced in his acquaintance with Land and Sea; but with the latter slowly. It was not until five centuries ago—and five centuries are but as a day, compared with the full stretch of history—that two weighty steps were taken.

One step was southward. One step was westward.

The African Continent, all along its northern region, had been the scene of very old-world history. But the south was shrouded in darkness. A brief glimmer of light, perhaps thrown there in Phenician days, had been long long lost sight of.

In the year A.D. 1486, a far leap from Phenician and Grecian days, Bartholomew Diaz made discovery of the Cape of Good Hope, and one year later Vasco da Gama sailed round it. These two explorers were only a little in advance of two greater voyagers. In 1492 Christopher Columbus started on his first cruise into the unknown West—and touched Land. Less than thirty years later, Magellan’s famous voyage was accomplished to those Straits, between Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego, which bear his name. By that time the existence of the American Continent had become an established fact.

But that Continent had to be searched out. And the Ocean, though its limits were widened in men’s imaginations, was very far from being mapped and fenced around with definite boundaries. Years of exploration still lay ahead; and many a valiant explorer had to fall a martyr in the cause of Science, before mystery should yield to knowledge.

Doubtless, in those days as in these, there was always somebody to ask, “But what is the use? What good can it do to us to learn that there are lands beyond the sea? What shall we gain by it all?”

Time alone, with its developments, with the growth of the human race, with the enormous possibilities then undreamt-of, could answer such questionings. Happily, brave explorers have seldom been lacking, who loving knowledge for its own sake have been content to labour patiently, not for money, not for fame, not for immediate results, but for the simple delight of better understanding the world around them, and for the benefit of future generations.

And indeed, if once we begin clearly to realise that the things which we see and hear, the wonders of Land and Ocean, are the outcome and expression of Divine Thought, we shall scarcely deem time wasted, which is spent in trying to find out a little more about those wonders.

CHAPTER II.

SALT WATER

THE annual stampede of Britons to the coast says much for our National belief in Sea-breezes. In other countries also people go to the sea for change; but perhaps nowhere does the rush excel that on our Island. This revivifying gift, though partly due to the wide and free expanse through which the breezes have travelled, is largely owing to the briny ocean with which they have been in contact.

Sea-water differs from rain-water, well-water, river-water. True, it is made up of all these, since sooner or later and in one mode or another all water on Earth finds its way to the Ocean. Water may travel openly by river-routes; it may creep silently by dark and devious underground passages; it may float lightly viâ cloudland; but in any case its goal is the sea.

Still, though the ocean includes in its composition every kind of land-water, Sea-water as such is different from them all. Not only in its vast extent, in its enormous depth, but in its strong flavour of Salt.

One of the commonest of substances is Salt. It is in the ground, in air, in water. We even know that it does not belong to our earth alone, but to many heavenly bodies also.

Perhaps one reason for this abundance, at least upon our Earth, is that it is necessary for life. There is salt in the make of blood and of brain, of muscle and of tendon. Salt is perpetually passing out of a man’s body; therefore continual fresh supplies of it are needed. Without a certain amount of salt in his food, he cannot keep in good health.

This at one time was not understood; and salt was looked upon as a mere luxury, easily to be dispensed with. Condemned criminals were forbidden that luxury; and they went through a good deal of suffering, the reason for which was not guessed. If plenty of animal and vegetable food was given to them, they managed to get along, since both contain salt; but if they were kept on purely farinaceous fare, they broke down.

Where all the salt in the Ocean comes from, is a complex question. Large supplies are brought down annually by rivers and streams, from various minerals in their beds, as well as from rock-salt regions. But if we ask, “How comes the rock-salt to be there?” we are told that it is a deposit, once formed beneath ocean-waters, or at least left by the drying up of salt lakes and seas. A proof of the latter theory is found in multitudes of sea-shells, often distributed through layers of rock-salt.

If much sea-salt came originally from rock-salt on land, and if rock-salt came originally from ocean-deposits, we are led into a curious circle of cause and effect—not unlike that of oak and acorn, or of hen and egg, with the attendant puzzle of—Which first? It is a query which we are not able to answer.

In former days the salt used for household and mercantile purposes was almost entirely prepared by the evaporation of sea-water. We no longer depend on this, however; and in England the sea-salt trade has gone down greatly before that of rock-salt, which is found to be the better for table use. It has not the same tendency to stick together in lumps, after being packed in sacks.

Great districts of rock-salt are found in many places—such as those in the Carpathian Mountains, in the Swiss Alps, in Germany, and in Great Britain. One huge mine in Galicia has been worked for six hundred years; and this supply is said to reach through about five hundred miles. From British works alone the quantity carried away every year amounts to a cubic mile of salt.

But land-supplies grow pale and insignificant before the quantities which float in the ocean. It has been reckoned that, if the waters of the whole ocean could be dried up, the amount of salt left lying on the ocean-bed would be something like four-and-a-half millions of cubic miles.

Such an enormous mass hardly conveys a clear idea. Let us think of one single cubic mile of sea-water, separated from the ocean, and see how much it would contain. First, the whole of that cubic mile of water has to be dried up; and then the materials left behind have to be weighed. We should find about thirty-three millions of tons of various kinds of substances, the names of which need not be given. We should also find of common salt a supply which, when weighed, would reach the great figure of one hundred and seventeen millions of tons. All this, be it remembered, floating unseen in a single cubic mile of water. No wonder the sea tastes salt.

In its make Water is always the same. Whether it be cold or hot, freezing or boiling, causes no difference. It consists of two gases, united; and the union is remarkable in kind. The two gases are not merely mixed together, as sand and sugar may be mixed. They are by the union changed into a fresh substance. For the time the gases exist no longer. In their stead, water has been formed.

And when the gases enter into this very close relationship, they do it always in the same manner. There is just so much of the one, and just so much of the other. One portion of hydrogen has to join with eight times as much by weight of oxygen—neither more nor less of either. The same is true, whether we are speaking of a great mass of water, or of the tiniest speck.

It is not actually correct to say, as is said above, that water “consists” of the two gases. So long as the water exists, the gases do not exist. And when, through the action of heat or electricity, the water is broken up and the gases reappear, then the water no longer exists. But at least we may say that it is the result of the uniting of those two gases, and that it can be made in no other way.

An interesting experiment has been tried. A certain amount of hydrogen gas and eight times as much of oxygen gas were weighed separately, by means of very delicate instruments. Then through great heat the two were caused to unite into water, and the water also was weighed. It was found to be just as heavy as the two gases together had been; and quite naturally so, since neither of the two gases had lost or gained in weight. This kind of union is called “chemical.”

French people are fond of “eau sucré.” A lump of sugar is dropped into a glass of water, and it disappears. But it has not been destroyed. It has not ceased to be sugar. No mysterious union has taken place between the sugar and the water. Neither water nor sugar has changed its nature; and no fresh substance has come into existence in their stead. The water is there, as it was before. The sugar is there too, not visible, but to be found out by our sense of taste. It has only been separated by the water into such minute particles that we cannot see them. This is a case of mixing, not of chemical union.

When we think of the characteristics of Sea Water, as compared with Fresh Water, we have to do with simple mixing. As sugar floats, unseen but not untasted, in tea or coffee; so salt floats, unseen but not untasted, in ocean waters.

Such a thing as absolutely pure water is very rare. No matter how clear a stream may seem to us, it holds a vast number of specks of material, collected from earth and air. Once a scientific man had some, most carefully distilled, which seemed to be of crystal purity. But he put it under the strong beam of an electric lamp, and, alas, for human powers! after so doing he could only declare that the idea of purity was ludicrous. If it is so with distilled water, the less said the better about common drinking-water. It may be well for our peace of mind that we have not stronger sight.

Ocean-water holds about two hundred times as much dissolved material as ordinary fresh water. The different kinds of substances found in any particular water-supply determine the character of that water, making it sweet or sour or salt, rendering it health-giving or death-dealing.

Something has been said about the drying away of sea-water, and the leaving of salt behind. A remarkable instance of salt thus left is seen in the Rann of Cutch, a flat Indian plain, about a hundred and ninety miles long, and half as wide.

During the south-west monsoon the ocean waters are forced by powerful winds up the Gulf of Cutch to a considerable height, overspreading the Rann, which for a time is turned into a shallow lake. When dry weather comes, the water vanishes, partly retiring, partly evaporating; and a salt-strewn desert is left, varied by sand-ridges, green spots, and little lakes, but covered principally by “sheets of salt crust.” My father, when there many years ago with his Regiment, noted down his impressions of the scene.

“From this spot”—the spot on which he stood—“the water is about eight miles distant, the intermediate space being a flat surface, entirely covered a quarter of an inch thick with salt in crystals, looking much like snow, in such quantities that it can be scraped up by the hand perfectly free from earth; and on all this space not a blade of grass to be seen.”

The same task is carried on by the working of sun-heat, as by the fire under a kettle. All day long in a warm climate the sun’s rays are busily at work, lifting from the ocean-surface a continuous stream of fine invisible vapour. The water is drawn up particle by particle, not in masses; and the sun’s rays have no power to lift the ocean-salt, which remains behind, floating still in the sea.

But when a strong wind lashes the surface into waves, and rends the tops of billows into fine spray, it often carries a great deal of salt to a distance. We know how salt may be tasted on the lips miles inland, and how windows near the coast become encrusted with it in stormy weather. Moving air, like moving water, can carry weight; and it is thus, through the action of moving air, and not through the heat of the sun, that we have our health-giving breezes off the sea, laden with salt.

CHAPTER III.

EARTH’S VAST OCEAN

“Thou great strong sea.”—Auberon Herbert.

IN these days we know the Ocean as one vast whole. Not like our early forefathers, standing on the brink, to gaze with awe-stricken eyes into mysterious distances, and to speculate upon the unknown.

Minor oceans do exist, certainly. We have the Atlantic, North and South; the Pacific, North and South; the Arctic, the Antarctic, and the Indian. Yet for us there is but one great world-wide Ocean, encircling the Earth, every part being in connection with every other part.

A drop of water which to-day floats in southern seas may, months or years hence, have found its way by currents into the far north. A speck of ice, at this moment fast in the rigid embrace of polar berg or floe, may, months or years hence, be washing to and fro in tropical waters.

A much greater area of water than of land is found upon the Earth’s surface. So vast is the amount of the former that, if the whole had to be put into separate vessels, each vessel being one cubic mile in size, the number of such vessels required would amount to no less than three hundred and thirty-five millions. This very large order speaks for itself.

The outer Crust of our Earth, taking land and sea together, may be divided into three distinct parts. Like most such divisions in Nature, the one is often found to glide by gentle stages into another.

We have, first, Land, rising above the sea-level, and consisting of plains, undulations, hills, mountains. It covers altogether less than one-third of the Earth’s surface, and it is called The Continental Area, though Islands as well as Continents belong to it.

We have, secondly, the Ocean-floor under deeper parts of the Ocean; that which lies beyond a depth of about two miles. This division has been described as the “great submerged plain,” and it comprises about one-half of the Earth’s surface. It is known as The Abysmal Area.

We have, thirdly, a middle region, which may be spoken of as a kind of borderland under the sea, connecting the dry land with the greater ocean-depths. It amounts to about one-sixth of the Earth’s surface, and it has been named The Transitional Area.

By “connecting” the two, I do not mean that it must always be between the two. It does very generally so lie, but there are exceptions. Some deeper portions of the sea are close to land, and some parts of the Transitional Area are found far out at sea.

The meaning of the word “Continental” needs no explanation; and the very word “Abysmal” carries its own sense. More, however, will be said in future chapters about those reaches of ocean known as the “Transitional Area.”

A curious law seems to have governed the grouping of land and water. Putting aside innumerable small islands, scattered about, we find that the great mass of land clusters towards and round the north pole, with a water-and-ice-filled hollow for its centre. While, on the contrary, the greater mass of water may be said to cluster towards and round the south pole, with—so far as we can conjecture—a large extent of land for its centre. The conditions of north and south thus seem to be exactly reversed.

Not long ago it was believed that the ocean’s floor might be a fairly close imitation of that which we see on land. The differences, however, have been found to be greater than was expected. Perhaps it is not surprising, when one thinks of the immense levelling power of water.

That must be a firm make of rock which can permanently resist the effect of sea waves breaking upon or near the shore. And even deeper down, where waves are not and currents may be slow, some movement must still exist, since the ocean is nowhere quite stagnant. Such movements, no matter how gentle, would tend to shift all loose and soft substances.

The ocean-bed is held to be generally flat, though with gradual slopes here and there, leading up or down to higher or lower levels. Many submarine mountains rear their heads, sometimes near the surface, sometimes above it. In places high mountain-ridges run for a long distance below the sea, with profound depths on either side; and these again often show their peaks, forming groups of islands.

Broad reaches of the ocean are between two and three miles deep, and here and there spots are found where the sounding-line goes sheer down three miles, four miles, five miles, even six miles, before touching bottom. These greater depressions have been named “Deeps.”

At least fifteen of them are known in the Atlantic, and twenty-four in the Pacific; many of the latter lying close to islands. Some are long in shape, some short; some are broad, some narrow. One of the most profound, and almost the only one known to exceed five thousand fathoms, lies towards the south-east of the Friendly Islands. A depth there has been found five hundred and thirty feet beyond five geographical miles; and five geographical miles are equal to almost six of our common miles.

For a good while the notion was entertained that, probably, the loftiest mountain-peak on land, and the deepest depth in the ocean, would about match one another, reckoned from the sea-level. But this particular “deep” in the Pacific sinks two thousand feet lower than the topmost peak on Earth rises. Mount Everest, in the Himalayas, is twenty-nine thousand feet high; and this ocean-depth is about thirty-one thousand feet deep. Only one other equal to it has yet been discovered.

No abyss divides England from France. The “silver streak,” though sufficient for purposes of defence, is comparatively shallow. All West Europe, indeed, rises from a plateau, reaching from Norway into the Atlantic, on no part of which is the water more than six hundred feet in depth. The “transitional area” in this case makes a true stepping-stone or ledge between dry land and ocean’s abyss.

But another great plateau in the Atlantic, which may be called the “backbone” of that Ocean, is far from land, running roughly from north to south. It follows the outlines of the eastern and western shores, and rises often to within a mile and a half of the surface. On either side of the “backbone,” which seems to be largely volcanic, is a deep trough, lying north and south, and varying in depth from two to four miles. This plateau unites Europe with Iceland; and it forms a bond between the Islands of the Azores, Ascension, and Tristan D’Acunha.

If by any means the whole ocean-surface could be lowered six hundred feet, remarkable results would be seen.

At once the British Isles would cease to be Islands. They would become a part of the Continent of Europe, joined thereto by dry land. The Hebrides, the Orkneys, the Shetlands, would share in this change. The Continents of Asia and North America would be united at the Behring Straits; Ceylon would find itself a part of India; Papua and Tasmania would be one with Australia; and all places hitherto on the coasts of different countries would find themselves six hundred feet above the sea.

Such a change in the position of the British Isles, transforming them into a Continental Country, would mean far-reaching consequences to ourselves as a People. One such consequence may be briefly given in the words of a recent newspaper article: “Dry up the Atlantic to the 100-fathom line, and in six months we should bear the load of Conscription as cheerfully and more efficiently than any nation in Europe.”

Suppose that another great fall in the ocean-surface could follow. Not this time to six hundred feet, but to three thousand feet, below its present level. The resulting alterations would be still more sweeping. Not only Iceland and the Färoe Islands, but Greenland also—and not only Greenland, but the Continent of North America itself—would become one with the Continent of Europe, no longer cut off from the Old World.

A word as to measurements. Two kinds of “miles” have been mentioned. There is the ordinary “Statute mile,” used in common conversation, which is 880 fathoms, or 1,760 yards, in length. There is also the “Geographical” or “Nautical” mile—the “knot” of our Navy—which is 1,013 fathoms or 2,026 yards in length.

The difference between the two is not far from one-eighth of a statute mile. Roughly, seven miles are equal to six knots. A fathom is six feet or two yards.

CHAPTER IV.

SUBJECT TO LAW

“Thou rulest the raging of the Sea.”

Psalm lxxxix. 9.

THINGS are what they are in this world very largely because of the pull of opposing forces, and among such forces not one is more universal than that of Gravity. Many causes beside Weight have their share in making our Earth what it is; but if Weight were banished from our midst, the Earth as we know it would exist no longer.

The only way to get rid of weight would be by getting rid of Gravity. And since no force in Nature acts more steadily and incessantly than this, we are no more likely to get rid of it than we are to get rid of the world itself.

Gravity, or Gravitation, or Attraction—it is known by all these names. Sometimes it is called a Law; sometimes a Force. Neither term may be counted amiss. No law is worth anything without a sufficient force to back it up; and no force is worth anything unless it acts according to law. But we might almost as reasonably call this behaviour of things “an Obedience” as “a Law.”

Each particle of each substance draws and is drawn by each other particle of every substance. And each body in the Universe, from a grain of sand to a sun, draws and is drawn by each other body, whether far or near. All these drawings are in obedience to that mysterious something—that force, or power, or influence—which has been named Attraction or Gravitation. So much we know; and beyond it we know very little as to the nature of the said “Attraction;” but we find that the outcome of it is Weight.

By means of weight, the sun, the moon, the planets, yes, and even the countless multitudes of stars, are kept in their paths; in each case the inward pulling being counterbalanced by the impetus and outward pulling of a rapid rush. By means of weight, houses, rocks, stones rest firmly on the earth; by means of weight, the atmosphere is bound to the earth, the Ocean to its bed. Had sea-water no weight it might be scattered as fine water-dust through Space.

A larger and heavier Earth would bind down the ocean yet more strongly, while a smaller and lighter Earth would have a weaker grip. Easily as the sea is now stirred by every passing breeze, an ocean such as ours on a little world like the Moon or Mercury would be more rapidly agitated. The waves would leap higher with less cause.

So the Ocean, like the Land, is subject to law, knowing neither repose nor action except in obedience to Nature’s forces.

When ocean-waters lie still as a mill-pond, they do so through an exact poise of contending powers. When waves rush high and currents pour strongly, each movement is still in strict obedience to governing forces, which are themselves governed by law. Each movement is due to a long series of past movements; and each in turn helps to bring about a long series of future movements. There are no breaks in the chain. Every effect is also a cause.

Currents here and drifts there; breezes here and hurricanes there; all these disturb the calm of the sea. Only for a brief spell, in one part or another, is the pull of opposing forces so far balanced that the water can lie still. And at most the stillness is comparative. Even in a so-called “dead calm” gentle heavings to and fro will be found. Absolute placidity in the ocean is a thing unknown.

Even when the waters are at their stillest they are always being drawn steadily towards Earth’s centre. A perfectly level ocean would mean each portion of its surface being equally distant from that centre. The ocean ever strives after this ideal, but never attains to it; yet, century after century that aim is pursued, with a perseverance which might afford a lesson to ourselves.

Despite all this change and restlessness, we talk of the ocean having a “level” surface. We picture it to our minds as being in outer shape the same as that of the Earth—a sphere. But this is not strictly true to fact.

If we could look upon the Earth, with large far-seeing eyes, from a few thousands of miles off, we should find curious irregularities in the watery outline. Instead of showing all round a smooth surface, the ocean would be found to rise here and sink there, to be in one part higher, in another part lower. A man roving over the ocean, all about the Earth, would have in places to ascend undulations like hills, almost high enough sometimes to be called mountains, in other parts to descend declivities.

Most of us have noticed in a cup filled with water, that the water-surface is not perfectly flat. Close to the sides of the cup may be noticed a distinct rise. It is the same in a tumbler, in a basin, in a slender glass tube. For the sides of the cup or tumbler or tube attract the water, drawing it upward; and this is known as Capillary Attraction.

With the ocean the very same thing is seen. If high land borders on deep water, the extra attraction of mountain-masses will act just as the sides of a cup or tumbler will act. They draw upward the water of the ocean to a higher level. When I say that this is “seen,” I do not mean that any careless looker-on will be aware of the fact. It has to be discovered by careful measurement.

In some cases a marked difference has been found. The enormous masses of the Himalayas, for instance, exert a powerful drawing upon the neighbouring sea; and at the delta of the Indus the ocean-level, in consequence of that attraction, is actually three hundred feet higher than on the coast of Ceylon.

Besides land attraction, winds have an extraordinary power to heap up waters in one place more than in another. To some slight extent this may be seen upon English shores, when a strong gale happens to blow landward at high tide. On such occasions the waters often rise far beyond their usual mark.

Mention was made earlier of those Phenicians who, having known an eastern ocean with tides, and a Mediterranean Sea without tides, must have been perplexed to find a western ocean which corresponded with the eastern in its ebb and flow.

We all know for ourselves in these later days, how the tides rise and fall around our coast, twice in twenty-four hours. Each high-water is twelve hours and twenty-five minutes later than the last; so each succeeding day sees a difference of fifty minutes in the time of high or of low tide.

To a very large extent Tides are due to the attractive power of the moon. They are due also to the sun, but in a much less degree, which at first sight seems singular, since the attraction of the sun, by reason of its greater size, far exceeds that of the moon. From the fact, however, that the powerful drawing of the sun comes from an immense distance, it follows that it has much less effect than the small attraction of the moon, which comes from very near at hand.

Her influence over our earth is exerted far more strongly with respect to those ocean-waters lying just under herself, and far less with respect to those waters on the farther side of the globe. The effect of these different pullings is to raise a double wave or swell,—one on the surface of the ocean just below the moon, and one on the opposite side of the earth. The waves mean high tides; and low tides occur at places half-way between them.

Were the whole Earth covered by one continuous sheet of water, these tidal waves would travel round and round the globe, in a fashion easy and pleasant for students of the subject. Unfortunately for the said students, their motions are very complicated. In the northern hemisphere, where land is abundant, the tidal waves are greatly interfered with by continents and islands. Often the most that each can do, as it sweeps along, is to send side-waves and currents journeying northward into channels and bays, estuaries and lesser seas.

Through the open ocean the tidal wave has no great height. Probably in central regions of the Pacific it rises only some three or four feet above the usual sea-level. But when the flow enters narrowing bays and channels, a very different result is seen; and the waters are often piled up in a wonderful manner,—as in the Bristol Channel, where the level at high tide is sometimes nearly forty feet above that at low tide.

A marked contrast to this is seen in the Mediterranean. There, as already said, practically no tides exist. The rise and fall amount at most to only a few inches. Instead of a wide entrance and a narrowing estuary, we have just the opposite—a narrow entrance and a widening sea beyond. Connection with the outside ocean is too restricted to admit of any full flow of the tidal wave.

Solar tides, or tides brought about by the sun’s attraction, are much the same in cause and effect as lunar tides, only far smaller in degree. When Sun and Moon happen to be on the same side of the Earth, or on different sides but in the same line, so that their combined pull is exerted in one direction, we have Spring Tides. These are always at the time of New Moon and Full Moon. Sun and Moon then work together, each helping the other in a common aim; and the ocean-waters rise higher and sink lower than at other times.

When Sun and Moon are so placed with regard to the Earth, that they exercise their pull in a cross direction, Neap Tides result,—that is tides which have small ebb and flow. In this case the sun hinders instead of helping the moon, and the moon does the same for the sun, each tending to counteract the work of the other.

Connected with and partly caused by the rise of the tide is the curious phenomenon known as a “Bore”—a single high wave, moving onward like a wall of water, with great rapidity and a roaring noise. More usually this belongs to a river, and thus it has not much connection with the subject of the ocean; but it is also sometimes seen in sharply narrowing estuaries or ocean inlets.

BORE OF THE TSIEN TANG KIANG

Face page 34

To the inhabitants of a flat and unprotected country, bordering on river or estuary, the bore is often a thing of terror, for its advent is uncertain and abrupt, and in its upward rush it sweeps everything before it. The entering of such a wave into the Severn is an almost daily event, and it reaches often a height of many feet. Bores are usual, too, in the River St. Lawrence, in the Hoogly, in an estuary of the Bay of Fundy, and in other places innumerable; and they vary in height from two or three feet to over twelve feet. The effect of such a wall of water as this, deluging low lands, carrying away trees and houses and living creatures, may be easily imagined.

CHAPTER V.

IN OCEAN DEPTHS

THROUGH ages of the world’s history, man knew nothing of the Ocean beyond its surface.

He could sail on the sea; he could bathe in the shallow waters near land. If a good swimmer, he might go farther out, and might even dive for one or two minutes out of sight. In more recent times, with the help of a diving-bell, he could descend thirty or forty feet; and in a diving-dress he might even, if experienced, get from one to two hundred feet down.

But that was all. Of the vast depths beyond he was sublimely ignorant. He did not so much as know of their existence. Until the late scientific expedition made in the vessel Challenger, that great world of the Under-Ocean was swathed in mystery.

Nothing is known of it now by direct personal observation. No living man may penetrate those depths. The only mode in which we can learn what is, what lives, what happens there, is by means of “soundings,” by sending down and drawing up specially prepared instruments, the reading of which gives us information about that Under-world.

Soundings made in earlier times did little more than tell navigators how deep the sea thereabout might be. Such instruments as were then used could neither work beyond a limited depth, nor say their say with accuracy.

Of late years immense improvements have taken place, both in the make of the machines employed, and in the methods of working them. Past soundings were few and unsystematic; whereas now they are many and by rule. Thermometers have been made which bring up from the bottom of the sea reports of the prevailing heat or cold, moving unaffected through warm or cold layers between. Specimens of the materials which lie on the ocean-floor have been brought to light, and analysed. Living creatures in great numbers have been hauled from their own domains, examined and classified.

All this means progress. And though, no doubt, fifty or a hundred years hence, that which we now know will be looked upon as the barest A B C of the science, still our knowledge is growing year by year. The Under-Ocean is no longer a vague fairy-land of possible mermaids, or a waste region of death.

A region of death in one sense it is and must be. All living creatures that die in the sea, unless devoured by other creatures, sink to the bottom, there to find a tomb. Covered at first by a vast winding-sheet of water, they may be slowly buried under the shifting mud and sand. But in this sense the whole Crust of Earth may be called one vast sepulchre, wherein all animals that die are entombed.

People are slow to realise how modern is our knowledge of ocean-depths. About three hundred years ago a famous navigator made the first sounding which went below two hundred fathoms—that is, about one hundred feet deeper than the height of Beachy Head from the shore. He at once decided that, by a happy chance, he had alighted upon the uttermost depth in the ocean.

To him it was an awe-inspiring profundity. Yet, when viewed beside such abysses as have been recently discovered, depths of five and six miles, his little “deep” was as a saucer beside a lake.

It is not easy to picture to ourselves the changeless calm of those abysses—those five or six miles of under-water, with nothing from sea-level to sea-floor to break the dead monotony.

Throughout such regions storms, no matter how terrible, have no power. Winds cannot reach them. When Ocean’s surface is lashed by a hurricane into wild commotion, that commotion is superficial. It means a furious stirring and flurry of upper layers; and it means no more.

If at the height of some fierce tornado, a sailor could leave his tossing straining ship, and could dive far into the sea, keeping breath and sense and life, he would soon quit the turmoil, and would find himself in a scene of deep repose. Strange to say, the idea of submarine ships actually doing this has been mooted, as one of the new projects in the beginning of the Twentieth Century.

Wave-motion does not descend much below the surface. It is believed that the depth of water affected by a wave is usually about equal to the space which divides crest from crest. So, if we are looking at little ripples, flowing one after another, with crests perhaps one foot apart, we may suppose that the water is disturbed by those ripples to a depth of about one foot. Or, if we are watching larger waves, with crests twenty feet apart, we may suppose the disturbance to reach down to a depth of some twenty feet. And if our gaze is fixed on dignified Atlantic rollers, with crests six or eight hundred feet apart, we may suppose that the sea is affected to a depth of six or eight hundred feet—less and less affected the deeper we go down.

Six or eight hundred feet, compared with six miles, are hardly more than a man’s skin compared with his body. And beyond the shallow depths where wind and wave have sway, we come to a region of profound calm.

This repose does not mean stagnation. Ocean’s waters are ever on the move, travelling this way and that way. Currents exist far below, as well as at the surface; but they are generally slow and placid, not rough and hurrying. Old Ocean’s excitability lies all outside. Superficially he is soon upset; but deep down he is composed.

A great deal of discussion has taken place as to possibilities of Light in those depths. Are they black with midnight darkness? or do faint glimmers of daylight creep through?

Ocean-water, like other water, is transparent. Any substance is transparent, when thin enough,—even gold. A very thin film of water is not, however, needed for transparency. Many feet, even many yards, may be seen through, if clear and pure. Few of us have not, at one time or another, looked down from a boat, to see golden sand, variegated pebbles, small fishes swimming about, at a considerable depth.

Thus with water, as with denser materials, transparency is merely a question of thickness. As the thickness increases, more and more rays of sunlight are taken captive, and the water becomes less and less translucent, till at length, if we could get deep enough, we should find ourselves to be surrounded with blackness.

Another feature of ocean-depths is that of immense pressure.

We bear a certain degree of it in that other and lighter ocean—the Atmosphere. A man of medium size has upon his body about thirty thousand pounds’ weight, or some fifteen pounds to the square inch. But this is nothing to what he would have to endure down in ocean-waters. At a depth of one mile, an extra ton would be piled upon each square inch of his body; two miles down, would mean two extra tons on each square inch; three miles down, three extra tons; and so on. The load would soon become intolerable.

For many years scientists maintained that in such depths no life could exist, since no bodies could withstand the awful pressure. Yet we now know that frail jelly-fish, fragile shell-inhabitants, do withstand it, flourishing there by myriads.

Perhaps the fact was somewhat overlooked, that the pressure upon a living creature is not only inwards from without, but also is outwards from within. This is true of ourselves in the ocean of air, breathing air. It is true of creatures in the ocean of water, breathing water.

Much less than the weight of thirty thousand pounds might crush a man flat, were it not for the resisting pressure from within. If for one instant he could empty his body of all inner air and liquids, and could so harden his skin that no air should squeeze through its pores, he would be pressed as flat as a pancake by the surrounding atmosphere.

A story has been told, illustrative of this. Once upon a time a clever fellow started an original idea. He proposed to make a balloon, which should mount skywards, not from being full of hydrogen gas, but from being emptied of air. Being then lighter than the atmosphere, it would, he said, of course rise.

So far as the reasoning went, it was faultless. It only did not go far enough.

The balloon being made, he named a day for its ascent, and asked many friends to witness his triumph. At the last moment, all air was withdrawn; and everybody waited in expectation, hoping to see the novel balloon skim lightly above their heads.

But the inventor, while using strong materials, had failed to make full allowance for the tremendous pressure of the air, when counteractive pressure from within should have been done away with. As the air was drawn out, the sides of the balloon collapsed, being crushed together as an empty egg-shell may be smashed in a boy’s hand. Instead of soaring gaily upward, the would-be aeronaut stood on earth, scanning with disappointed eyes a flattened and useless shell.

A diver going down into the sea has a much increased weight upon his body; but he does not suffer from it to a serious extent, provided that he is not raised or lowered too fast. Much depends upon this. Both men and beasts can endure a good deal of alteration in the degree of pressure, whether from air or from water; but they cannot bear very abrupt changes. Hearts and lungs need time for growing accustomed to a fresh condition. In early days of diving this was not understood, and some divers lost their lives through being too hurriedly hauled up.

The same has been noticed in animals brought quickly from great depths. They have been constantly found in the net or trawl, dying or dead, their bodies swollen and even bursting from the lessening of pressure. It was natural that at first the belief should arise of Life being in those parts impossible. Now we know that animals die in the act of being drawn up, and that they live and flourish in profound depths, unaffected by the vast load of water.

The weight that a man can endure is not to be compared with what fragile sea-creatures thrive under. Beyond a depth of some two hundred feet or more, the pressure becomes too great for any human beings; yet animals are found at depths of three or four miles. But the fact that man breathes air, and that animals in the sea breathe, in a sense, water, makes an enormous difference in their power to resist pressure.

One might suppose that the terrific weight of miles of water would squeeze lower layers to a smaller bulk. Water is, however, very difficult to compress; unlike air.

At the bottom of the sea, four or five miles deep, the weight is said to be equal to about four tons upon the square inch. If this tremendous load were pressing upon a mass of air, eleven thousand cubic feet in quantity, the whole would be crushed together into only twenty-two cubic feet. But the same weight pressing upon the same quantity of sea-water, would merely reduce its size to ten thousand cubic feet. So there is not much difference between the make of sea-water near the surface and sea-water at a great depth.

Not only are ocean’s depths calm and free from storms; not only are they black with midnight darkness; not only are they heavy with the weight of miles of water overhead; but also for the most part they are cold.

Changes from season to season, like changes of weather, are superficial. At a depth of about six hundred feet, Seasons have ceased to be. There, summer and winter, autumn and spring, exist no longer. The dead level of calm and darkness is also a dead level of uniform weather and unalterable climate. Where changes of cold and heat do come about, they are very uncertain, and usually they are due to other causes than those which bring about the succession of seasons upon Earth.

Many remarkable facts have lately come to light with respect to Ocean’s temperatures. In far northern and far southern regions, near the two poles, the whole sea is very cold. One might expect the converse of this in tropical regions—a whole sea intensely warm. But this we do not find. The shallower parts—those included in the hundred-fathom limit—may be nearly as warm below as above. When, however, deep-sea soundings are made, when the registering thermometer is despatched on its mission of inquiry miles below the surface, then the report brought up is generally of great cold.

In almost all deeper parts, the tale is told of a frigid under-layer,—of water nearly and sometimes quite down to the freezing-point of fresh water. This, not only in Polar Seas, not only in Temperate Oceans, but in the hottest portions of the Tropics. The Atlantic, near the equator, is icy in its depths.

A reckoning has been made that, if the floor of the whole ocean, omitting shallower parts, could be divided into one hundred equal portions, ninety-two of those portions would be found covered by water at a temperature of less than 40°; and only eight of them would lie under warm water. The vast mass of the ocean is cold, with a thin warm layer over certain districts.

Little doubt can there be that this under-layer is largely fed from polar regions.

We know that cold ocean-rivers pour from north-polar regions to the south, both in the Atlantic and in the Pacific. A general creeping under-flow of icy waters towards the equator evidently balances the general surface drift of warm waters towards the poles. Since cold water is heavier than warm, it would naturally find its way to lower depths, leaving the warm light liquid to float on the top.

In the Mediterranean Sea a marked contrast is found. There no ice-cold layer is spread over the bottom; and the water in its uttermost depths—over two miles and a quarter—does not sink below the temperature of 54° F. The heat of the sun in South Europe can hardly be compared with the heat of the sun over the Indian Ocean. Yet the latter has water far below the surface down to at least 35°.

Practically the Mediterranean, despite its depth, may be looked upon as an inland sea. The one opening which connects it with the open ocean is not only comparatively narrow, but also is shallow, being less than two hundred fathoms deep. The water on this dividing ridge remains at about 55°, and the Mediterranean throughout, to its greatest depths, keeps to about that same degree of warmth. No entrance is afforded to the heavy cold currents from polar regions.

The Red Sea is separated from the Indian Ocean by a similar ridge, and the same result is seen there. Over the floor of the Indian Ocean lies a carpet of chill water. But the whole body of the Red Sea never sinks, in summer or winter, below 70° F. Here, too, the cold streams are not able to surmount the barrier.

In many deep mid-ocean hollows, cut off by surrounding sub-ocean walls of rock, the same is found again—warm water within the hollow, cold water on the ocean-bed outside.

CHAPTER VI.

RIVERS IN THE SEA

“Sinuous or straight, now rapid and now slow.”

Cowper.

“As winds that coerce the sea.”

C. G. Rossetti.

ACTUAL Rivers in the Ocean; distinct streams of water, flowing over a bed of water, with banks of water. Not merely one or two such rivers, but scores of them, hundreds of them, great and small, in all parts of the world.

Chief perhaps in importance is the Gulf Stream, that vast flood which pours out of the Gulf of Mexico, and acts as a winter heating apparatus for the west of Europe. Though by no means the largest of ocean streams, it is one of the most useful to man.

After quitting the Gulf, it hurries at speed through the Straits of Florida; then spreads out into a river, about fifty miles wide and over two thousand feet deep, journeying at a rate of some sixty miles in twelve hours.

For a while it hugs the American coast; but, happily for Europe, it forsakes this friend of its youth, and wanders to the north-eastward across the Atlantic.

To call it a “river” is no mere fiction of speech. Near Halifax the separation between warm and cold water is so sharp, that those on board a ship may know what latitude they have reached, on entering or leaving the stream, by simply dipping a bucket in the water and taking the temperature. Literally the Gulf Stream is a warm river, flowing over a bed of cold water, with cold-water banks.