Daisy of Old Meadow

Agnes Giberne

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

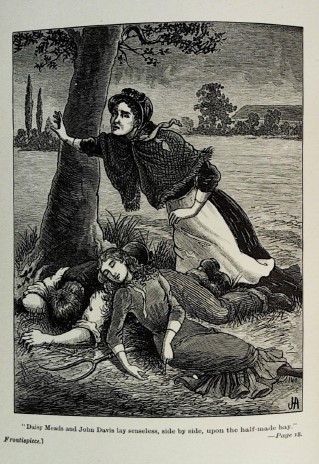

Daisy Meads and John Davis lay senseless, side by side,

upon the half-made hay. Frontispiece.

DAISY OF "OLD MEADOW."

BY

AGNES GIBERNE,

AUTHOR OF

"OLD UMBRELLAS;" "SUN, MOON, AND STARS;" "ST. AUSTIN'S LODGE;"

"BERYL AND PEARL;" ETC.

"If I have made gold my hope . . . this also were an iniquity

to be punished."—JOB xxxi.

"Lay not up for yourselves treasures upon earth."—MATT. vi.

LONDON

JAMES NISBET & CO., LIMITED

21 BERNERS STREET

PREFACE.

THE following pages are issued with two objects:—

First; they may be used for daily meditation on rising or retiring to rest, in the quiet chamber, when none but God is near.

Secondly; for short services in sick chambers, or for invalids. Many a child of God suffers from infirmities of such a nature that none but a very short service can be borne. This may be carried out by reading the whole chapter, or a portion of it, from which the text is taken; then the address, and the poem. This may be preceded or followed by a short prayer, thus compressing the entire service within ten minutes or a quarter of an hour.

I am aware of the many and great deficiencies which mark these addresses. But they have been issued with one desire and one aim—to glorify Jesus. May He thus use them, by His Holy Spirit, for this end is my earnest prayer!

ST. MARY'S, HASTINGS,

October, 1885.

CONTENTS.

CHAP.

I. THE WIDOW'S OPINIONS

II. STRUCK

III. DAISY'S NEEDS

IV. AN UNTIDY HOME

V. A DANGER ESCAPED

VI. TWO NURSES

VII. PAST DAYS

VIII. GOLD

IX. OLD ISAAC

X. DAISY'S WISH

XI. A RICE PUDDING

XII. DAISY'S TROUBLE

XIII. GONE

XIV. A MOTHER'S WORK

XV. SORRY AND GLAD

XVI. ISAAC'S LOSS

XVII. MONEY AGAIN

XVIII. OUT OF DANGER

DAISY OF "OLD MEADOW."

CHAPTER I.

THE WIDOW'S OPINIONS.

"HE'S the crookedest crabbedest cantankerousest old fellow ever I came across, and that's all I have to say! And she's a little angel, if ever there was one, and that's all I have to say too!"

It might have been all that Betsy Simmons had to say, but it certainly was not all that she did say. For, finding her hearer not indisposed to listen, she started off afresh. Betsy Simmons was fresh-complexioned, large in make, and verging on fifty. The other, a younger woman by many years, was quiet and thoughtful in look, with a face and a manner some degrees superior to her poor style of dress.

"He comes in here of a morning, every day, punctual as the clock is on the stroke of nine. And he pokes into everything and fingers everything, afore he'll have his penn'orth or two penn'orth of this or that, till I'm driven nigh crazy. 'Tisn't much more than a penn'orth that he'll take, commonly. But there's often a deal more of fuss with customers about a penn'orth than about a pound's worth. Well, and I know one thing, and that is that if he's after starving anybody, it is Miss Meads and not Mr. Meads, and that you may be sure. He's an old skinflint, and all the world knows it. They do say," and Mrs. Simmons lowered her voice, "they do say as he broke his wife's heart; and I shouldn't wonder but he's going near to break his daughter's too. Not as she speaks a word of complaint—no, she isn't that sort, little angel as she is."

Mary Davis, the listener, seemed more moved than might have been expected under the circumstances. She lifted the corner of her faded shawl to wipe away a tear.

"And they do say—" pursued Mrs. Simmons—but the advent of another customer caused her to break off. "I'll come back to you, Mrs. Davis," she said, with a nod. "Don't you hurry away." And Mary Davis waited patiently, making no protest.

A brown-skinned child, in tattered frock and curl-papers, stood gazing about her with curious eyes. "Please'm," she said, "mother wants two penn'orth of tea, please."

Two pennies dropped on the counter from the little soiled hand. Mrs. Simmons proceeded to weigh the article, and to twist up the packet. "If I was you, Janey Humphrey, I wouldn't be seen out in that trim," she said reprovingly, while so occupied. "Curl-papers in broad daylight,—and face and hands as soap and water haven't come near to for twenty-four hours past. It isn't decent nor respectable, and you'd ought to be ashamed of yourself."

"I've got to mind the baby," said Janey, in a manner of abashed self-excuse.

"That don't make no difference," said Mrs. Simmons decisively. "Nor it wouldn't if you had to mind a dozen babies. If there's time to eat there's time to wash, and I suppose you ain't too busy to eat. And if you haven't time to get your hair out of curl-papers, you'd best never put it in."

"Mother told me to, 'cause it's the school feast, and she wanted me to look 'speckrable," said Janey.

"You'd look a deal more respectable with your hair brushed plain behind your ears. I can tell you the ladies will be none the better pleased with you, for having a lot of frizzly corkscrews over your head—and you may tell your mother so, if you like. I declare I'd well-nigh forgotten it was the school feast this afternoon. Well—get along with you, child—but mind you don't come here again looking like a guy."

Betsy Simmons was counted a privileged person, in the matter of advice-giving. The widow of a sailor, childless, and alone in the world, she had held this little shop during some fifteen years past, and was known in the neighbourhood as no less kind-hearted than outspoken. She sold groceries, green-groceries, and confectioneries, and she drove a brisk trade, being content with small gains.

It was a quaint little shop, standing in the middle of the chief street of a large village, called Banks. There were other shops in the same street. Near the upper end stood a Church, with an ivy-covered square tower, and a Rectory-house and schools adjoining.

Exactly opposite the shop was to be seen a very old and worn-out house, surrounded by a small and very untidy garden. The village stretched well around and beyond it.

For many years "Old Meadow"—so the house was named—had been inhabited by two maiden sisters, whose father had once owned and farmed some hundreds of acres in the neighbourhood. But he and his family had met with reverses, and gradually their possessions had dwindled down to just the ancient house and its garden. When the last aged Miss Meads died, the house and garden went to a cousin, Isaac Meads by name; and it was now about a year since Isaac Meads had settled down there, with his daughter.

"Old Meadow" had not been too well kept in the latter days of old Miss Meads and her sister; but certainly its appearance had not improved since the coming of their cousin. The house was low and spreading, and was covered with masses of ivy, which hung low over the cracked and broken panes of the latticed windows, and served to hide dilapidations in the roof. Huge hollyhocks flourished within the garden wall, and weeds grew in profusion. All this could be seen from the open door of Mrs. Simmons' shop.

Mary Davis was the wife of a working man, who had just come to the place in search of employment. There was a market-town, called Little Sutton, about two miles distant, where work was rather plentiful; and as rent was lower and food was cheaper in Banks than in Little Sutton, many workmen preferred to make their homes in the village, walking to and from the town every day.

Betsy Simmons dearly liked a little gossip with her customers, and she was particularly taken with the gentle face and manner of Mary Davis. Usually she was reserved in her remarks about her opposite neighbour, especially with strangers. It happened, however, that the old man, Isaac Meads, was in the shop when Mary Davis entered it; and after his departure Mrs. Simmons had naturally mentioned his name.

Thereupon Mary Davis had asked some questions about him, showing so marked an interest in the subject that Betsy Simmons had been drawn on to say more than was usual with her. She descanted on the odd ways of the old man, and on the sweetness of his young daughter, Daisy Meads, until the entrance of Janey Humphrey made a break. After Janey's departure, the thread of the talk seemed broken.

"That child, now!" Mrs. Simmons said,—not returning at once to the subject of the Meads family, as Mary Davis had hoped she might do,—"she's a fair specimen, Mrs. Davis, of what you'll see here, and better than ordinary I may say. Her father's a well-meaning man, and he don't drink often, which isn't too common." Mary Davis sighed quietly. "And he brings home his wages pretty regular; and that isn't too common neither. And her mother's a well-meaning woman too—wants to do her best, I don't doubt. Yes, I'll say that of Janet Humphrey—she does want to do her best. But dear me, she's never straight. Go when you will, the place is all of a mess, and the children are dirty, and nothing is where it should be. Mrs. Humphrey's for ever cleaning up, and never clean. That's what I say. Always cleaning, and never clean! It's the way of the folks about here. She don't have a go at her work, and get it done, and make things tidy; but she potters about, and she washes a little, and scrubs a little, and cooks a little, and don't finish off anything out of hand. Works like a slave, of course—folks of that sort mostly do,—and has nothing to show for it. I wonder she hasn't driven her husband to the bad long ago; for he never has a dinner fit to eat, nor a tidy corner to sit down in. And yet she isn't lazy, nor a gossip."

"It's a pity," Mary Davis said absently. "But, Mrs. Simmons, there was something you began to say about Miss Meads over the way."

"To be sure,—yes. Well, as I was saying—What was it I was saying?"

"He'd broke his wife's heart, and was near breaking of his daughter's," said Mary Davis promptly.

"Just so," said Mrs. Simmons, with emphasis. "Not as she complains. O no, she isn't of the grumbling sort. She don't say a word: only goes about smiling, with that sweet face of hers, like a little angel. She's scarce more than a child to look upon, and yet she's got a sort of old way, and there's trouble in her face, beside the sweetness; trouble of a sort, as if she'd had no proper childhood. Well, but I was going to say about the old man, and I'm near forgetting; they do say he isn't near so poor as he makes believe to be. It's no business of yours nor mine, I dare say, but I have heard said as he's got a lot of money stowed away somewhere. He don't make no use of it, if he has. He's that shabby, he goes about scarce fit to be seen; and he's that particular, he'd sooner go without a meal, I do believe, than pay one farthing more for it than he means to. Times and again I've let him have goods under the price, sooner than he should go off empty-handed. Not as I'd mind about him; but Miss Daisy's sweet face comes up, and I can't say a word. Yes, I call her 'Miss Daisy' most commonly. She don't mind, and it seems to suit her better than 'Miss Meads.'"

Mary Davis murmured something about the old man being fond of his daughter.

"Couldn't say as to that," responded Mrs. Simmons. "He mighty fond of himself. Maybe he's fond of her too, after a sort,—but it's a queer sort. If you want to catch a sight of Miss Daisy, you'd best be at the school feast this afternoon. Lots of folks go. It is in the big meadow round near Farmer Grismond's. She's sure to be there, for she has a class in the Sunday-school."

CHAPTER II.

STRUCK!

THE "big meadow round near Farmer Grismond's" presented a gay scene that afternoon. Two long tables were early spread at its upper end, under the shade of some large elms; and four rows of bright-faced children went in extensively for tea and buns and cake. Some of the children's mothers had kept them on short commons since breakfast, in preparation for the school feast: so no wonder the little things were hungry.

The clergyman, Mr. Roper, was present; and his wife, with several other ladies to help, was very busy, pouring out tea and handing plates of bread-and-butter. Mrs. Roper was a kind-hearted little lady, always busy about something.

The big meadow belonged to Farmer Grismond, and the annual June school feast had taken place in it for many a year past. He never refused leave,—not even when he had not succeeded in carrying his hay beforehand; but he rarely failed in this. The school children always hoped that they might find a few ridges or cocks remaining in which to riot; and the ladies were never sorry for so easy a method of amusing the children. But Farmer Grismond naturally preferred to have it all safely stacked as soon as possible.

Although hay making was just over in the "big meadow," it was going on still in the adjoining field. The sun shone brightly, but Farmer Grismond saw signs of a speedy change in the weather, and he could allow no delay. So, while the children ran races and scrambled for sugar-plums and played games in the next meadow, he was hard at work. The mown grass lay in long ridges, and women in print sun-bonnets stood among men in smock-frocks, all busily engaged with their pronged forks, tossing and turning. For this was a good many years ago; and Farmer Grismond liked old-fashioned ways; and hay making machines had not yet obtained entrance upon his farm.

Mary Davis found her way to the big meadow in the course of the afternoon, as advised by Mrs. Simmons. Her husband was at work that day among Farmer Grismond's haymakers. He was a mason, and work was promised him in Little Sutton a week later; but in his young days he had been a country boy, and had practised haymaking. So, hearing that the farmer wanted additional help, he had offered himself. Mary Davis was thankful for any employment for him, thankful for anything that should keep him for a few hours out of the public-house. That was John Davis' weakness. He was an affectionate husband, and really a well-meaning man, in a general way; but he was weak as water, utterly without strength of principle or resolution; and he seldom came out of a public-house quite sober.

Mary Davis took a look at the haymakers first, and had a kind word from Farmer Grismond, a stout burly man, with a face as red as his own pocket-handkerchief, from the blaze of the sun. "Good day, Mrs. Davis,—I hope you are quite well," he said cheerily, having already seen her. "Your husband is doing capitally for an unpractised hand,—clever fellow, I should say. I wish I had a dozen more like him. But it's of no use. The rain is coming too quick."

"You don't think it will rain to-day, sir, do you?" asked Mary.

He pointed towards a bank of dark clouds, which Mary had not noticed. "If it keeps off two hours I shall be surprised," he said.

Farmer Grismond was much too busy for chitchat, so Mary made her way into the next field. She asked one or two people quietly "If they could tell her which was Miss Meads." But the answer in each case was: "No, I don't see her just now; she's somewhere near." So Mary stood about, and waited patiently.

Farmer Grismond was in the right. Other people, less observant, did not take notice of the coming change, till suddenly a cloud rolled over the face of the sun; and then everybody looked up startled, and many said, "Dear me, is it going to rain?" Yet still the games and shouts and merry laughter went on. One or two remarked that the absence of sunshine was comfortable; it had been so very hot. There was no coolness yet, however, but only a close heavy heat, like that of an oven.

The greater number of the children had collected near the lower part of the field, in the vicinity of a large cow-house, and some were running in and out of the cow-house. Mrs. Roper kept guard over them there; and several of her friends about this time said good-bye to her, and went home, expecting rain. Mrs. Roper, however, did not like to cut the children's pleasure short, and she hoped the threatening shower might keep off for an hour or two yet.

At the upper end of the field, quite far away from the rest, several children were having a merry game among the trees, and somebody said to Mary, "That's Daisy Meads' class, over yonder." So Mary immediately made her way all across the meadow, and watched the game. She noticed at once a rather older girl with the little ones, slight and small in figure, and dressed in a plain stuff dress and brown bonnet. At first Mary took her for one of the older school children, till she heard her called, "Teacher, Teacher!" and till she saw that the little pale face within the brown bonnet was scarcely that of a child. It was a sweet face, delicate and small, with a smile which came and went like sunshine, and there was something round the mouth which told of long endurance of trouble.

Mary Davis had found what she wanted. That was Daisy Meads; and she knew it.

She could not interrupt the game: so she waited still. Presently some of the children began to flag, and Daisy Meads herself seemed to have had enough. She stood, with her back against a tree, near Mary Davis, her hand pressed against her side.

"You're tired, Miss," Mary ventured to say; and Daisy, looking round, saw her for the first time.

"Yes, I can't run any more. It gives me a 'stitch,'" said Daisy. "Are you one of the mothers? I don't seem to know you—and yet—"

A puzzled expression came into her face, and she looked earnestly at Mary.

"I'm only just come to Banks, and I haven't got any children," said Mary. "My husband's John Davis, and he's haymaking in the next field."

"I thought I didn't exactly know you," said Daisy. "And yet—it is curious, but I seem to remember your face."

"I shouldn't wonder but you do, Miss Daisy, seeing I've had you in my arms many a time."

Daisy came nearer, looking earnestly still. "Then I do know you," she said. "I thought I did. And you are Nurse—my own dear Nursie."

Daisy did not hesitate a moment, but threw her arms round Mary Davis, and kissed her warmly. No spectators were near except the little children; but she would probably have done the same in any case.

"Dear good kind Nursie, you can't think how often I have longed to see you. Why did you never write? But I don't wonder, after the way things happened. Only I always knew you loved me still. I did feel so lonely after you went—and I do still," Daisy said sadly, speaking in a low quick voice. "Nursie, he is worse than ever. I can't do anything with him."

"Only God can, Miss Daisy."

Daisy's eyes were full of tears, but a smile broke over her face.

"Yes," she said, "God can, and that is my comfort. I am always praying for him. But he won't hear about religion, and he seems to care for nothing at all but just trying to save and lay by. And he is growing an old man now. It does seem so sad. But I try to do everything I can to please him, and perhaps some day things will be different. And you are married, Nursie. Your name used not to be Davis. Ought I to call you 'Mrs. Davis?' It does not sound natural."

"I shouldn't like to be anything but 'Nurse' to you, Miss Daisy," said Mary. "I've been married close upon four years."

"That was three years after you left us. Yes, I was only a little thing, nine years old then, but I remember all perfectly, and the comfort that you were to poor mother."

"And she died, Miss Daisy? But I don't need to ask. I knew she couldn't last long."

"Only a few weeks after you left us," said Daisy, her face growing sorrowful. "It was very hard to bear the loss of both together. And the time has seemed so long and slow since. I can't believe sometimes that I am only sixteen. I feel so old and grave."

"You are not well, Miss Daisy," said Mary anxiously.

"Yes, I think I am well, only old," said Daisy, lifting her soft child-like face. "I seem to have lived such a very long time. But tell me about your husband, Nursie. Is he good and kind?"

"He's kind, Miss Daisy, commonly. If only it wasn't for the—"

Mary did not finish her sentence, but Daisy understood. How many a poor wife has to say the same. A good husband, a kind husband, an affectionate husband—a man who would be all these, if only it wasn't for the drink!

Daisy looked her sympathy, and would have expressed it in words, but a sudden interruption came. A flash of brilliant lightning shone in their faces, and a heavy crash of thunder followed.

A general rush of children might be seen in the distance, towards the cow-house, encouraged by Mrs. Roper; and the little ones of Daisy's class made a like rush to the shelter of the tall elm trees, some of them screaming. But Daisy sprang after them.

"Stop, all of you," she cried. "You must not go under the trees. Children, do as you are told. Come to me."

Terrified as they were, they obeyed her, and a frightened cluster drew round the girlish figure. A second flash and crash came, and some of them wailed piteously.

"Now listen to me," said Daisy Meads steadily. "You mustn't, any of you, go near a single tree. It is very very dangerous to do so in a storm. If the lightning strikes anywhere it always strikes something tall. If a tree were struck, and you were standing at the bottom, you might be killed. There is another flash. But you need not mind the noise of the thunder, for thunder never hurts anybody."

The peal was so loud that Daisy had to pause. Mary Davis looked wonderingly at her, as she stood, pale and quiet, among the clinging children.

"Hadn't we better get them under shelter somewhere, Miss Daisy?" she asked. "There's a shed in the next field, where they are haymaking, quite away from trees, and much nearer than the cow-house."

"Then that will do," said Daisy decisively.

She pulled up one little crying girl from the ground, and Mary Davis carried the youngest. As they hurried through the nearest gate, rain pattered heavily around them, and the haymakers, leaving their now useless work, sped away in different directions for shelter. One man, not far from the hut, lifted a pile of hay on his fork, held it erect over his head, and under this shelter proceeded deliberately towards a tree, smiling at his own cleverness. The children had by this time clustered into the hut, and Daisy stood panting in the doorway. She gave one look, and exclaimed: "Oh, how mad!"

Mary Davis glanced in the same direction, not understanding. "That's my husband, Miss Daisy," she said. "He seems bent on keeping himself dry. But I'd best go and tell him not to go near the trees, if it's dangerous." Mary had her doubts whether Daisy's idea were not a delusion, being ignorant, as many people are, about the nature of lightning.

"Your husband! But he mustn't do that," said Daisy breathlessly. She did not wait to explain, but darted straight out into the rain, and reached the man. "Put your fork down,—don't hold it up!" she cried. "Don't you know that's dangerous? There's iron on it."

John Davis stood still, and looked at Daisy in surprise. He did not know what she meant, and he was in no hurry to lower his new-fangled umbrella, of which, indeed, he felt rather proud. Daisy did not try the effect of argument. She put out her little hand impulsively to grasp the handle, intending to drag it from him. John swerved, loosening instinctively his own grasp, and her hand only fell upon his arm. Another instant, and the uplifted hayfork would have fallen.

But it was just too late. A zigzag stream of blue light leapt out from the black cloud overhead, accompanied by a harsh and rattling peal of thunder. Daisy Meads and John Davis lay senseless, side by side, upon the half-made hay.

CHAPTER III.

DAISY'S NEEDS.

ISAAC MEADS had not been to the school feast. He did not trouble himself about such frivolities. What mattered buns and banners, and tea and games to him? Or, in other words, what mattered the good and the happiness and the innocent enjoyment of two hundred children, for whom others were thinking and working? Isaac Meads had not learnt to care for others' joys.

It had been very much against the old man's will that Daisy had undertaken a class in the Sunday-school. She would never have undertaken it without his consent, and probably no one less gently and kindly persistent than Mrs. Roper would have won his consent. Once yielded, he did not withdraw it, but he objected still, in his sullen silent fashion. Isaac Meads was a very silent, and oftentimes a very sullen man. He did not fly into violent passions, like some people, but he sulked and grumbled, and spent a great part of his life in a most uncomfortable fog, so far as his own temper was concerned. The worst of such a fog is that it does not only affect oneself, but touches those about one. So poor Daisy knew a great deal already about that particular kind of foggy atmosphere in a house. It is a much worse kind than the yellowest and densest of London fogs.

Isaac had never taught in a Sunday-school himself, and therefore he did not see why Daisy should do so. There was a difference in the two cases: for if Isaac had been set down with a dozen children, and desired to give them a lesson out of the Bible, he would not have had the least idea what to say; whereas Daisy's mind was so full of thoughts that she could never get half she wanted into the time allowed. But Isaac reasoned out matters from his own notions, and not from actual facts: so no wonder his conclusions were wrong. He looked upon Sunday-schools and Churches, and religion altogether, as very tiresome and superfluous matters, and he took good care for his own part to have as little as possible to do with them.

There was one thing which Isaac Meads really loved, one thing which he really did count worth working for, and striving for, and living for. Not religion, not God, not the great future! Isaac could not for a moment say with David, "THOU, O God, art the thing that I long for;" and he was content to leave the question of his own home and happiness through the awful countless ages of a coming eternity just to chance. But there was one thing that Isaac Meads did love, did long for, did count worthy of his best attention; and that one thing was MONEY.

Whether he had much or little of it, few people knew; but whether he loved what he had nobody could doubt. Whether such as he had was stored up in his house, or put away in a savings bank, the world around was ignorant; but whether his money possessions were deeply treasured in his own heart, everybody might see.

Isaac loved money. He did not merely like it, did not merely enjoy what it could bring him. He loved money for its own sake, with a real heart-devotion for the poor senseless gold which could give him no love in return. He loved money with that heart-love which a man can bestow upon one object only, everything and everybody else being secondary to it. There was a throne in Isaac Meads' heart, as there is a throne in the heart of every man, belonging by right to God Himself: and that throne, in the secret chamber of his being, was occupied by Money.

Mrs. Simmons had seemed doubtful whether he really cared for his daughter Daisy.

It was quite true, as she had said, that he cared for himself best. Love to self always goes with love for money.

But he loved Daisy too, only it was with a lower and secondary sort of affection. He was proud of her, and he leant upon her in his dull home life. He never felt comfortable when she was away. He was a man with no friends, no occupation; with nothing to do except to take care of his money. He was past earning it now; so all the energies of his feeble old age were bent to the task of saving instead of getting. He grudged the spending of a single unnecessary penny.

It was money itself, not money's worth, which Isaac so loved. That terrible heart disease, "the root of all evil," as money-love is called in the Bible, takes different forms with different people; and in old Isaac Meads it was to be seen in its most grovelling form of all, the sheer love of base coin.

He sat dismally alone that sunny afternoon in the dingy front parlour of "Old Meadow." There were some books in a book-case at one end of the room, but Isaac Meads never dreamt of indulging in the unprofitable occupation of reading. Why should he? If he had read fifty books, he would not have gained a penny by so doing. He had only one mode of testing the worth of things or actions. Would they "bring in" so much? If not, they had no charm for him. Poor old Isaac!

Daisy had made the room very neat before she went. She did most of the house-work herself, with only a girl to help. Isaac grumbled often at the expense of the girl, and in his heart he wished often to dismiss her altogether. While Daisy was a child some such help had been an absolute necessity, but now that she was sixteen and a child no longer, he did not see why Daisy should not do the whole herself. It was a good-sized house, to be sure, but some rooms were shut up; and though Daisy had a strong love for keeping everything clean, like her mother before her, Isaac had not the least objection to any amount of dust.

He thought he would speak about this to Daisy, on her return from the school feast, and would insist on a change. Then he wondered whether Daisy would perhaps get some tea and a bun, and so would not need anything more when she came back. If so, her presence at the feast was a saving to his pocket, and he was glad of it.

Isaac did not look a happy old man, sitting there all alone, buried in these thoughts, with his wrinkled forehead, and dull eyes, and dropping lower jaw. He was not at all an attractive or lovable old man. Daisy worked hard to keep his clothes tidy, but he persisted in wearing an old coat of tindery texture, which almost dropped into holes with its own weight. He had one other suit, very aged, yet tolerably respectable, but he would scarcely ever put it on, for he was terribly afraid of its wearing out and having to be replaced. He often told Daisy that she was doing her best to ruin him; and if she ventured to ask anything for herself, he sometimes positively cried like a little child. He did not see why Daisy's clothes, once bought, needed ever to wear out.

The room grew dark, as the old man sat musing, for clouds had crept over the sun, and a stormy blackness gathered round. Isaac hardly noticed the change, until he was startled by a sudden and blinding flash, straight in his eyes, followed by a loud thunder-crash.

He pushed his chair back into the shade between the two windows, disliking the glare. If Daisy had been present he would have affected indifference: but being alone he did not disguise from himself a feeling of uneasiness, almost amounting to fear. The lightning blazed, and the thunder crashed again and again; and he pushed his chair yet farther into the shade. There had not been so heavy a storm for a long while in Banks. Isaac muttered once or twice, "Shouldn't wonder if something was struck, I shouldn't! Why don't Daisy make haste home?"