Roy: A Tale in the Days of Sir John Moore

Agnes Giberne

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

"Dost thou remember, soldier old and hoary,

The days we fought and conquered, side by side,

On fields of bank, famous now in story,

Where Britons triumphed, And where Britons died?"

* * * * * * *

"Dost thou remember all those marches weary,

From gathering foes, to reach Coruña's shore?

Who can forget that midnight sad and dreary,

When in his grave we laid the noble Moore?

But ere he died, our General heard us cheering

And saw us charge with Victory's flag unfurled,—

And then he slept, without a moment's fearing

For British soldiers conquering all the world."

NORMAN MACLEOD.

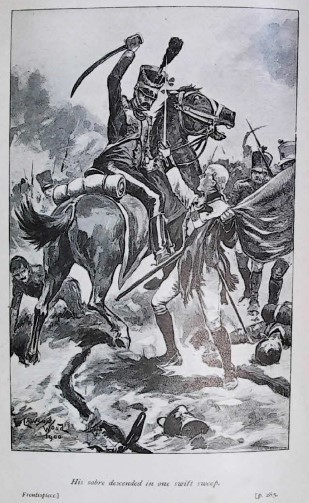

His sabre descended in one swift sweep.

Frontispiece.

ROY

A TALE IN THE DAYS OF

SIR JOHN MOORE

BY

AGNES GIBERNE

AUTHOR OF "COULYNG CASTLE"

"AIMÉE, A TALE OF THE DAYS OF JAMES II."

ETC. ETC.

"Duris non Frangor"

LONDON

C. ARTHUR PEARSON, LIMITED

HENRIETTA STREET

1901

DEDICATED

BY EXPRESS PERMISSION

TO

FIELD-MARSHAL THE RIGHT HON.

G. J. VISCOUNT WOLSELEY

K.P., G.C.B., G.C.M.G., COL.R.H.G.

COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF

VICTOR AT TEL-EL-KEBIR

ETC. ETC.

PREFACE

IN the following pages I have tried to give a faithful picture of life in England and in France during the first decade of the Nineteenth Century. The invasion scare, the state of National feeling in our land, the conditions which prevailed among British prisoners in France, the descriptions of French conscripts and French dungeons, etc., are in accordance with reality. My authorities have been many, including volumes written and published at the time, long since out of print. One chief authority for dungeon-scenes is the "Narrative" of Major-General Lord Blayney, himself four years a captive at Verdun and elsewhere; but his account by no means stands alone. My aim has been in no case to overdraw, but to be true to those things which actually were.

Some old MS. letters, handed down in my own family, belonging to that date, have been no inconsiderable help.

In the central figure of the tale I have sought to draw a portrait, true again to life, of him who in an age of British heroes ranked par excellence as England's foremost soldier-hero; of him about whom, twenty years later, Sir George Napier wrote—"That great and good soldier ... to whom I looked up as the first of men;" of him about whom, half a lifetime after the Battle of Coruña, Sir Charles Napier, the famous conqueror of Scinde, could sadly say—"Thirty-eight years ago the great Moore fell: I have never seen his equal since!"

To these past testimonies may be added that of Lord Wolseley, who has kindly granted his permission for the dedication of this book to himself. In a speech made not long ago, Lord Wolseley spoke of Moore as "one of the greatest soldiers we ever had," who, "if he had not been killed at Coruña, would probably have been the Commander in the Peninsular Wars, and have won the great battle which annihilated Napoleon's power at Waterloo."

And indeed, the extraordinary lustre of Sir John Moore's character and career, together with the radiant glory with which the close of his life was crowned, form a picture scarcely to be excelled. No man ever lived more exclusively, or fought with more absolute self-abandonment, for his country—"that country," to quote once more from Sir George Napier, "which he loved with an ardour equal to the Roman patriot's, and had served to the hour of his death with a zeal and gallantry equalled by few, surpassed by none." This at a time, it may be added, when the very existence of Great Britain as a Nation was at stake.

Perhaps the best clue to the keynote of Moore's history may be found in a sentence culled from one of his letters to his mother—"And so I hope that, whatever happens, England will not be able to say we have not done our duty."

CONTENTS

CHAP.

I. A TRIP TO PARIS IN 1803

II. SWEET POLLY'S GRENADIER

III. A MAN AMONG TEN THOUSAND

IV. DOLEFUL TIDINGS

V. GENERAL INDIGNATION

VI. THE DUKE'S PARTICULAR FRIEND

VII. PRISONERS OF WAR

VIII. THE THREATENED INVASION

IX. OUR HERO

X. THE FRENCH FLEET SIGNALLED

XI. A MISTAKEN READING

XII. ORDERED TO VERDUN

XIII. A FRENCH CONSCRIPT

XIV. IN A FORTIFIED TOWN

XV. FROM OVER THE WATER

XVI. ORDERED TO VALENCIENNES

XVII. IN THE YEAR 1807

XVIII. ALTERED LOOKS

XIX. ROY'S IMPRUDENCE

XX. ORDERED TO BITCHE

XXI. A GLIMPSE OF LOVELY POLLY

XXII. THE WAY OF THE WIND

XXIII. IN VIEW OF CAPTAIN PEIRCE

XXIV. A BITTER EXPERIENCE

XXV. LIFE IN A FRENCH DUNGEON

XXVI. A PRISON TRAGEDY

XXVII. A BARRED WINDOW

XXVIII. MOST FRIENDLY OF FRENCHMEN

XXIX. THE DEAR OLD COUNTRY

XXX. SIR JOHN MOORE

XXXI. ORDERED TO SPAIN

XXXII. TWO MIGHTY MEN

XXXIII. CAPTIVES STILL

XXXIV. AT SALAMANCA

XXXV. MOORE'S BOLD VENTURE

XXXVI. A HAZARDOUS RETREAT

XXXVII. A VISIT FROM MOORE BY NIGHT

XXXVIII. THE BATTLE OF CORUÑA

XXXIX. MOORE'S LAST VICTORY

XL. A WARRIOR TAKING HIS REST

XLI. AT VERDUN ONCE MORE

XLII. LUCILLE'S APPEAL

XLIII. THE RELEASE OF ONE

ILLUSTRATIONS

HIS SABRE DESCENDED IN ONE SWIFT SWEEP Frontispiece

PROMPTLY DOWN UPON THIS WITH BOTH KNEES WENT THE TALL GRENADIER

HE MOUNTED AND RODE OFF

"I SAY, HADN'T YOU BETTER GIVE ME THAT LITTLE THING TO HOLD?"

HE HAD TO WORK AT THE BAR IN A DIFFICULT AND CRAMPED POSITION

SIR JOHN GLANCED ROUND BEFORE SPEAKING

ROY

A TALE IN THE DAYS OF

SIR JOHN MOORE

CHAPTER I

A TRIP TO PARIS IN 1803

"YOU don't mean to say it, my dear sir? You're absolutely jesting. I'm compelled to believe that you are pleased to talk nonsense. To take the boy! Impossible!"

"I never was more sober in my life, I do assure you, ma'am."

"The thing is incredible. No, sir, I cannot believe it. 'Tis bad enough that you should be going abroad at all, at this time—you and your wife. But to place an innocent babe of nine years in the power of that wicked Corsican! Twelve years old, say you! Nay, the twins' birthday is not till June. Roy is but eleven yet, and none would guess him to be over nine. Well, well, 'tis much the same. My dear sir, war is a certainty. We shall be embroiled with France before six weeks are ended."

"That is as may be. We intend to be at home again long before six weeks are gone by. A fortnight in Paris—nothing more. The opportunity is not to be lost; and as you know, all the world is going to Paris. So pray be easy in your mind."

Colonel Baron adjusted his rigid stock, and held his square chin aloft, looking over it with a benevolent though combative air towards the lady opposite. Mrs. Bryce was a family friend of long standing, and she might say what she chose. But nothing was further from his intentions than to alter his plans, merely because Mrs. Bryce or Mrs. Anybody Else chose to volunteer unasked advice. There was a spice of obstinacy in the gallant Colonel's composition.

Despite civilian dress—swallow-tailed coat, brass buttons, long flapped waistcoat, white frilled shirt-front, and velvet knee-breeches, with silk stockings—the Colonel was a thorough soldier in appearance. He had not yet left middle age behind, and he was still spare in figure, and upright as a dart.

Mrs. Bryce, a lively woman, in age perhaps somewhere about thirty-five, had bright twinkling eyes. She was dressed much à la mode, in the then fashionable figured muslin, made long and clinging, her white stockings and velvet shoes showing through it in front. The bonnet was of bright blue; and a silk spencer, of the same colour, was cut low, a large handkerchief covering her shoulders. A short veil descended below her eyes. She used her hands a good deal, flirting them about as she talked.

Upon an old-fashioned sofa, with prim high back and arms, and a long 'sofa-table' in front, sat the Colonel's wife, Mrs. Baron, a very graceful figure, young still, and in manner slightly languishing. Though it was early in the afternoon, she wore a low-necked frock, with a scarf over it; and her fair hands toyed with a handsome fan. A white crape turban was wound about her head. Beside her was Mr. Bryce, a short man, clothed in blue swallow-tailed coat and brass buttons—frock-coats being then unknown. His face was deeply scored and corrugated with smallpox.

The wide low room, with its large centre-table and ponderous furniture, had one other inmate, and this was a lovely young girl, in a short-waisted and short-sleeved frock of white muslin. A pink scarf was round her neck; dainty pink sandalled shoes were on her small high-instepped feet; long kid gloves covered the slender round arms; a fur-trimmed pink pelisse lay on a chair near; and from the huge pink bonnet on her head tall white ostrich feathers pointed skyward. Polly Keene was on a visit to the Barons, and she had just come in from a stroll with Mr. and Mrs. Bryce. Young ladies, ninety or a hundred years ago, did not commonly venture alone beyond the garden, but waited for proper protection. Polly had the softest brown velvet eyes imaginable, a delicate blush-rose complexion, and a pretty, arch manner.

Upon a side-table stood cake and wine, together with a piled up pyramid of fruit, for the benefit of callers. Afternoon tea was an unknown institution; and the fashionable dinner-hour varied between four and half-past five o'clock.

"A fortnight in Paris! And what of Nap meanwhile?" vivaciously demanded Mrs. Bryce. "What of old Boney? That is the question, my dear sir. What may not that wicked tyrant be after next?"

"Buonaparte has a good deal to answer for, ma'am, but I do not imagine that he will have the responsibility of hindering this little scheme of ours."

Mrs. Bryce turned herself briskly towards the sofa.

"If I were you, Harriette, I'd refuse to go. Then at least you will not have it on your conscience, if everything gets askew."

Mrs. Baron's large grey eyes gazed dreamily towards the speaker.

"My dear Harriette, wake up, I entreat of you. Pray listen to me. Doubtless all the world is off to France. Nothing more likely, since half the world consists of idiots, and another half of madmen. That is small reason why you two need to comport yourselves like either."

"Do you truly suppose there will be war again so soon?" asked Mrs. Baron incredulously.

"Do I suppose? Why, everybody knows it. Colonel Baron knows it. There can't be any reasonable doubt about the matter. The Treaty of Amiens is practically at an end already. Nap has broken his pledges again and again. And this last demand of his—why, nothing could be more iniquitous."

"Dear me, has he made any fresh demand?" Mrs. Baron's eyes went in appeal to her husband, for she had no great faith in Mrs. Bryce's judgment. The Colonel had no chance of responding.

"Even you can't sure have forgot that, my dear Harriette! He desires that we should give over to his tender mercies the unfortunate Bourbon Princes who have fled to us for refuge. And no doubt in the end he would demand all the refugees of the Revolution. He might as well demand England herself! And he will demand that too, in no long time. 'Tis an open secret that he is already making preparations for the invasion of our country."

"Boney does not believe that England, single-handed, will dare to oppose him," remarked Mr. Bryce. "He considers that a nation of seventeen million inhabitants is certain to go down before a nation of forty millions."

"Let him but come, and he'll learn his mistake," declared the valiant lady. "But you, Harriette—with public affairs in this state—you positively intend to let your crazy husband drag you across the Channel!"

"But I do not think my husband crazy, and I wish very much to go," she said, slightly pouting. "I have never been out of England. The wars have always hindered me, when I could have gone."

"And you absolutely mean to take the young ones, too!"

"We intend to take Roy," said the Colonel, as his wife's eyes once more appealed to him.

"I never heard such a scheme in my life! To take the boy away from his schooling—"

"No; his school has just been broken up for some weeks. Several cases of smallpox; so it is considered best."

"And Molly! Not Molly too?"

"No, not Molly. One will be enough." Colonel Baron did not wish to betray that he had strenuously opposed the plan, and had given in with reluctance to his wife's entreaties.

"I thought the two never had been parted."

"It is time such fantasies should be broken through. Roy must go to a boarding-school in the autumn, and this will pave the way."

Mrs. Baron lifted a lace pocket-handkerchief to her eyes.

"My dear heart—a school five miles off! You will think nothing of it when the time arrives," urged the Colonel. He had won his wife's consent to the boarding-school in the autumn only that morning, by yielding to her wish that Roy should go to Paris. The Colonel's graceful wife was something of a spoilt child in her ways, and he seldom had the will to oppose her seriously.

"Indeed, I should say so too," struck in Mrs. Bryce. "You don't desire to turn him into a nincompoop; and between you and Molly, my dear Harriette, he hasn't a chance, And what's to become of Molly?"

Mrs. Baron was still gently dabbing her eyes with the square of lace; and the Colonel answered—"My wife's stepmother wishes to have Molly in Bath for a visit. She will travel thither with Polly early next week."

"Too much gadding about! Not the sort of way I was brought up, nor you either. But everything is turned upside down in these days. And you've persuaded Captain Ivor to go too!"

"Undoubtedly Den will accompany us."

"And you're content to put yourselves into the clutches of that miserable Boney!"

"My dear madam, the First Consul does not wage war on unoffending travellers."

"Boney doesn't care what he does, so long as he can get his own way."

"He will at least act in accordance with the laws of civilised nations."

"Not he! Boney makes his own laws to suit himself."

"Well, well, my dear madam, we view these things differently. I have made up my mind. My wife has never been into France, and we may not have another opportunity for many years to come."

"Likely enough—while the Corsican lives!" muttered Mrs. Bryce.

The end window opened upon a verandah, and just outside this window, which had been thrown wide open, for it was an unusually hot spring day, a boy lay flat upon the ground, shaping a small wooden boat with his penknife. At the first mention of his name, a fair curly head popped up and popped down again. A recurrence of the word "Roy" brought up the head a second time, and two wide grey eyes stared eagerly over the low sill into the room. He might have been seen easily enough, but people were too busy to look that way. Then again the head vanished, and its owner lay motionless, apparently listening. After which he rolled away, jumped up, and scampered to the schoolroom at the back of the house.

It was a good-sized house, with a nice garden, in the outskirts of London; a much more limited London than the great metropolis of our day, though even then Englishmen were wont to describe it as "vast." Trafalgar Square and Regent Street were unbuilt; Pimlico consisted of bare rough ground, and Moorfields of genuine swampy fields; and the City was still a fashionable place of residence.

Roy Baron was a handsome lad, well set-up, straight and spirited, though small for his age, and, as Mrs. Bryce had intimated, childish in appearance. He had on a blue cloth jacket, with trousers and waistcoat of the same material. Knickerbockers were unknown. Children and older boys wore loose trousers, while tights and uncovered stockings were reserved for grown-up gentlemen. In a few weeks Roy would exchange his cloth waistcoat and trousers for linen ditto, either white or striped. Boys' hair was not cropped so closely in the year 1803 as in the Nineties; and a mass of tight curls clustered over Roy's head.

The year 1803! Think what that means.

Napoleon Buonaparte was alive—not only alive, but in full vigour; he had entered on his career of conquest, and the world was in terror of his name. Nelson was alive; five years earlier he had won the great Battle of the Nile, two years earlier the great Battle of Copenhagen, though he had not yet won his crowning victory of Trafalgar which established British supremacy over the ocean. Wellington was alive; but his then name of Sir Arthur Wellesley had not become widely famous, and no one could guess that one day he would be the Iron Duke of world-wide celebrity. Sir John Moore, the future Hero of Coruña, was alive, and though not knighted was already the foremost British soldier of his age.

Napoleon was not yet Emperor of the French. He was climbing towards that goal, but thus far he had not advanced beyond being First Consul in the Republic.

The peace between England and France, lasting somewhat over twelve months, had been hardly more than an armed and uncertain truce, a mere slight break in long years of intermittent warfare. As the old king, George III., remarked at the time, it was 'an experimental peace,' and few had hopes of its long continuance. For the Firebrand was still in Europe, and barrels of gunpowder lay on all sides. Both before the peace began, and also while it continued, Napoleon indulged in many speculative threats of a future invasion of England, and preparations were said to be at this date actually begun.

England alone of all the nations stood erect, and fearlessly looked the tyrant in the face. And Great Britain, with all her pluck, had then but a tiny army, and few fortifications; while her chief defence, the fleet, though splendidly manned, was weak indeed compared with the mighty armament which she now possesses.

Whether the peace would last, or whether it would speedily end, depended mainly on the will of one man, an ambitious and reckless despot, who cared not a jot what rivers of French and English blood he might cause to flow, nor how many thousands of French and English widows' hearts might be broken, so long as he could indulge to the full his lust of conquest, and could obtain plenty of what he called "glory." Another and truer name might easily have been found.

CHAPTER II

SWEET POLLY'S GRENADIER

"MOLLY, Molly—listen! I've something to tell you."

Roy jerked a story-book out of his twin-sister's hands. It was not a handsome and prettily illustrated volume, like those now in vogue, being bound in dull boards, with woodcuts fantastically hideous. But Molly knew nothing better, and she loved reading, while Roy hated it—unless he found a book about battles. Molly was even smaller and younger-looking for her years than Roy. She had a pale little face, with anxious black eyes, and short dark hair brushed smoothly behind her ears. She wore a frock of thick blue stuff, short-waisted and low-necked, while her thin arms were bare.

The schoolroom served also as a playroom. Its furniture was scanty, including no easy-chairs. Mrs. Baron was a mother unusually given to the expression of tender feeling, in a sterner age than ours. But she never dreamt of giving her children opportunities for lounging. They had to grow up straight-backed, whatever it might cost them.

In this room Roy and Molly had done all their lessons together, till Roy reached the age of nine years; and the day on which he began to attend a large boys' school had witnessed the first deep desolation of little Molly's heart. An ever-present dread was upon her of the coming time—she knew it must come—when he would be sent away to a boarding-school, and she would be left alone.

Roy seated himself astride on a chair, with his face to the back, and poured out his tale. Molly listened in dead silence, staring hard at the opposite wall. If Roy did not mind about leaving her, she was not going to show how much she cared about losing him.

"And I shall write and tell you all I see in France," were his concluding words. "And you'll have Jack and Polly, you know—and Bob Monke too."

Would Roy have thought Jack and Polly and Bob enough if he had been the one to stay at home? That was the question in Molly's heart. But she only said, with a catch of her breath—

"I shouldn't like to be you, to have listened on the sly. It was mean."

The word stung sharply. Roy always pictured his own future in connection with a scarlet coat, a three-cornered cocked hat, a beautiful pigtail, and the stiffest of military stocks to hold up his chin. He knew something of a soldier's sense of honour, and even now, small though he was, he counted himself quite equal to fighting his country's battles. And that he—Roy Baron, son of a Colonel in His Majesty's Guards—should be accused by a girl of "meanness!"

"It was horridly mean," repeated Molly. "Prying on the sly, and then coming and telling me. If I had done such a thing, you'd have been the first to say it was wrong."

Roy stood upright.

"You needn't have told it me like that," he said reproachfully. "But I wouldn't be mean for anything, and I'm going to tell papa."

He did not ask his twin to go with him, and Molly was keenly conscious of the omission. He marched off alone, carrying his head as high as if the military stock already encircled his throat. There was a pause in the conversation, as he entered the drawing-room.

"Run away, Roy," said the Colonel. "We are busy."

"Please, sir, may I say something first?" Roy stood in front of his father, facing him resolutely.

"Well, be quick, my boy."

Roy's honest grey eyes met those of the Colonel. "I was out there," he said, pointing to the verandah, "and I heard something. I didn't know it was a secret, and I listened. I heard about going to Paris, and I went and told Molly. She said it was mean of me, and I—couldn't be mean, sir."

"No, Roy, I'm sure you couldn't." The Colonel spoke gravely, while delighted at his boy's openness.

"I didn't mean any harm, sir; I won't ever listen again."

"Quite right; never listen to anything you are not intended to know," agreed the Colonel. "You should have told us that you were there. And if I had found you out, listening, I should certainly have blamed you. But as you have voluntarily confessed, we will say no more about the matter. Now you may run away."

Roy bounded off, in the best of spirits; and the pretty girl, with tall feathers in her bonnet, glided softly in his wake. She did not follow him far. She saw him vanish towards the garden, and she went towards the schoolroom. For Roy had told Molly about the Paris plan, and Polly guessed what that would be to Molly.

Mary Keene and her brother John, commonly known as "Polly" and "Jack," were not really cousins to the twins, though treated as such. Their widowed grandmother, Mrs. Keene, had some fourteen years earlier married a second time, rather late in life; and her new husband, Mr. Fairbank, had one daughter, Harriette, wife of Colonel—then Captain—Baron of the Guards. Two or three years later her grandchildren, Jack and Polly, were left orphans, and were adopted by Mr. and Mrs. Fairbank. When Mr. Fairbank died, his twice-widowed wife took up her abode in Bath, at that date a fashionable place of residence for "the quality." Jack, who was a year or two older than Polly, had just been gazetted to a regiment of the line, quartered in Bath.

Molly was very fond of Polly and of Jack; but no one could be to her like her twin-brother, and Roy's indifference had cut her to the quick. When Polly came in she at once detected a little heap in the corner of the schoolroom, and heard a smothered sob. She drew off her gloves, made her way to the corner, sat down upon the ground, and put a pair of gentle arms round the child.

"Fie, little Molly, fie! This won't do at all. Crying to have to go home with me. That is wrong and silly. And so unkind, too. I wanted so much to have dear little Molly; and now I know she does not care to come. Molly, you little goose, don't you know people can't be always together? And you and I can't alter the world, to please ourselves. Roy is glad to go to Paris, of course. Fie, fie, Molly! cheer up, and don't be doleful. If you are unhappy, it makes other people unhappy; and that is such a pity. You don't want to make me cry too, do you?"

The elder girl's eyes had a look in them of tears not far distant; as she bent over the child.

"Other people have troubles as well as you, little Moll. We don't all—I mean they don't all—talk about their troubles. It is of no use. Things have to be borne, and crying does no good. So stop your tears, and think how agreeable it will be to see my grandmother and Jack, and the Pump Room, and all the fine ladies and gentlemen walking about in their gay clothes."

A squeeze of Molly's arms came in reply.

"There will be Admiral and Mrs. Peirce to see; for the Admiral is now on shore, and they are in Bath. And little Will Peirce, who soon is to be a middy in His Majesty's Navy. And my cousin, Bob Monke, who is at school there. And Jack shall show himself off to you in his new scarlet coat. I am proud of him, for Jack is everything in the world to me. No, not everything, but a great deal, as Roy is to you. Yet I do not expect to keep Jack always by my side. He will have to go some day, and to fight for Old England. And when that day comes I will bid him good-bye with a smile, for I would not be a drag upon him, And Roy will go too, and you will bear it bravely, little Moll, like a soldier's daughter."

The soft caressing voice, the cool rose-leaf cheek against her own, the lovely dark eyes smiling upon her, all comforted Molly; and she clung to Polly, and cried away half her pain.

"Don't tell Roy," she begged presently. "He doesn't mind, and he must not think I care."

"Why not? That is naughty pride, Moll. It is always the women who care—not the men." Polly held up her head, and a far-away look crept into the sweet eyes. "Dear, you must expect it to be so. Men have so much to do and to think about. But we have time to grieve when they go to fight. And they are always so glad to go."

"Are they?" a deep quiet voice asked, close to her side; and Polly started strangely. For a moment her tiny shell-pink ears became crimson, and then she looked up, smiling.

"How do you do, Captain Ivor?"

Denham Ivor in his uniform—large-skirted military coat, black gaiters, white breeches, pigtail, and gold-laced cocked hat in hand—looked even taller than when out of it; and at all times he was wont to overtop the average man. He had a fine face, well-browned, with regular features and dark eyes, ordinarily calm, and he bore his head in a stately fashion, while his manners were marked by a grave courtesy which might seem strange beside modern freedom. As he looked down upon Polly a subdued glow awoke in those serious eyes.

Polly had not sprung up. She was still kneeling on the floor beside Molly, and her slim figure in its white frock looked very childlike. The flush had died as fast as it had arisen. Molly was clinging to her with hidden face, and for an instant the fresh voice failed to reach the younger girl's understanding. Then Molly became aware of another spectator, and, quitting her hold, she fled from the room. Polly stood up gracefully.

"We will now go to the drawing-room," she suggested.

"Nay, wait a moment, I entreat. One instant—" and the bronzed face had grown pale. "I beseech of you to listen to me. For indeed, madam, I have somewhat to say which I can no longer resolve to keep to myself. No—not even for one more day. Somewhat that you alone can answer—thereby making me the most happy or the most miserable of men."

A tiny gleam came to Polly's downcast eyes.

"If you have aught that is weighty to say, it may be that I could but refer you to my grandmother," she suggested demurely.

"But perhaps you can divine what that weighty thing is! And what if already I have written to your grandmother, and if Mrs. Fairbank has graciously consented to my suit? For indeed it is even so."

Young ladies did not give themselves away too cheaply in those days. Polly was barely eighteen, but for all that she had a very dainty air of dignity. And if during past weeks she had gone through some troublous hours, recognising how much she cared for Captain Ivor, and wondering, despite his marked attentions, whether he really cared for her, she was not going to admit as much in any haste to the individual in question. So she dropped an elegant little curtsey, and asked with the most innocent air imaginable—

"Then pray, sir, what may be your will?"

"Sweet Polly, may I speak?"

A solid square stool, well adapted for present purposes, was close at hand; and promptly down upon this with both knees went the tall grenadier, in the most approved fashion of his day. Sweet Polly could not long stand out against this earnest pleading. So, with a show of coy reserve, she gradually yielded, intimating that she did like him just a little; that some day or other she thought she could be his wife; that meantime she would manage somehow to keep him in her memory.

Promptly down upon this with both knees

went the tall grenadier.

"And next week you are away to Paris," she said, perhaps secretly wondering why he did not spend his leave in Bath. "For a whole fortnight."

"I could wish I were not going; but all is arranged, and the Colonel depends upon me. I must not fail him now at the last. If I can see my way to return at the end of a se'nnight, I will assuredly do so. If not—I shall still have a fortnight after we come home. I shall know what to do with that time, sweetheart."

CHAPTER III

A MAN AMONG TEN THOUSAND

HALF-AN-HOUR later, Denham Ivor, with Roy by his side, walked down the street, his grave face alight with a new joy. Roy, ever his devoted admirer, glanced upward once and again with boyish wonder. He had never seen that look before. He decided that the journey into France was as delightful in prospect to Denham as to himself.

"And Molly needn't mind," he said, carrying on his own line of thought, confident that it fitted in with Denham's. "'We shan't be gone only a fortnight. I don't see why she should care."

"Well, no. A fortnight is a mere nothing, Roy."

Half-way down the next street Ivor stood still abruptly. The front door of a house opened, and a man came quickly out, close to him and Roy. Denham's hand was lifted in an instant salute, and Roy followed his example with amusing promptitude.

A remarkable man! Nobody casting one glance in his direction could fail to cast a second. Equal to Ivor in height, gracefully built, every inch a soldier, with a figure and face alike faultless in outlines, he could not but draw attention. So young still in look and air that none would have guessed him to be already over forty in age, already a Lieutenant-General in rank, there was about him an extraordinary and commanding force; and while the large brilliant hazel eyes, under their dark arched brows, were brimming with laughter at Roy's comical imitation of Denham, their slightest glance was of a kind to search men's hearts, to enforce instant obedience. His was, indeed, a singularly noble bearing.

Ivor was no longer utterly absorbed in thoughts of Polly. Another supreme passion of his being had come to the front. Roy, keeping as always one eye upon Denham, while taking note of all else around, saw with fresh wonder the look in his face—a look of reverent devotion and love. Never before had the boy seen these two together.

"Ivor! I expected to come across you somewhere. All your people well? So Colonel Baron is off to France."

"Yes, sir. I am going with him."

"Ha!" thoughtfully. "Well, have your little jaunt, by all means. It may be your last chance for a good while. Mischief lies ahead."

"That seems to be the general opinion, sir."

"No doubt about it. War will be declared, to a dead certainty, before many weeks are over. But matters are not yet quite ripe. You will have time for a glance at Versailles. After that, the deluge! I hope I may have you to serve under me, wherever I am ordered, when the rupture takes place."

"And I, sir, could desire nothing in life more!"

Those brilliant eyes met his. "What!—nothing! No fair lady in the question, to carry off your more ardent longings!"

Ivor's bronzed cheek took a slightly deeper dye, though he answered decisively—"You know me well enough, sir, to believe that no claim in all the world could come before that."

The radiant smile would have been answer enough, without words.

"I do know you well enough. None the less, if I be not greatly mistaken, you will have somewhat to tell me by and by."

"Yes, sir. Miss Keene and I are engaged."

"Already! You have been expeditious. But I suspected as much, and you have my most hearty congratulations. And still you go to Paris! For how long?"

"At the most a fortnight, sir. It may be less."

"That is well. No saying how soon troubles may break out. Good-bye, for the moment. I shall see you in a few weeks; and what may have happened before then, in these tempestuous days, he would be a rash man that should foretell with confidence."

With a markedly kind and cordial farewell the speaker passed on, Roy saying eagerly, so soon as he was beyond ear-shot—

"Den, was that General Moore? I'm sure it is General Moore. I saw him once, you know—ever so long ago."

Rash indeed would any man have been to foretell the events which, beginning in the near future, were to shape the pathways of those three! Little dreamt Roy, in his boyish half-puzzled interest, that long years were to pass before ever again his eyes should rest upon that soldierly face and form. Little dreamt Ivor, glad in the thought of Moore's confidence, Moore's wish, that never, never again in this life, would he stand in the presence of the man who was to him more than the whole world beside—in a sense more than even Polly, passionately as he loved Polly.

His feeling for John Moore partook, indeed, rather of the nature of idolatry. The love of man for man is so distinct from the love of man for woman, that the one cannot be compared with the other, the one cannot interfere with the other. From very boyhood Denham had revered and worshipped Moore, with that reverent worship which can only be called out by the superlatively good and great and lovable. It had grown to be part of Denham's nature, part of his being. Polly was the one woman on earth for him. But Moore was the one man whom he longed to follow, to whom he looked up as to a superior being, with whom he craved to be, for whom he would joyously have died. No other affection could detract from this devotion.

Roy's remark was unnoticed, perhaps unheard. Ivor stood, gazing steadfastly, until his chief was out of sight. Those who knew and adored Moore—and they were many in number—could scarcely take their eyes and attention from him when he was within sight.

It is to be feared that Polly found small leisure thereafter for meditating on the childish woes of Molly, so full was her head of the brave young Grenadier Captain who had vowed to devote his life to her.

One fortnight of separation, and then she would have him again, and hers would be the ineffable delight of showing off her brave lover among Bath friends. How they would one and all envy Polly!

A touch of feminine vanity crept in here, though Polly's whole heart was given to Denham. But in his deeper love for her, there was no thought of what others might say. He would doubtless be proud of the fair young creature whom he had won; yet in his love no room remained for any such puerile element.

He stood much alone in the world as regarded kinship, having been left an orphan at an early age, under the guardianship of Colonel Baron, his father's cousin, and having no brothers, sisters, or other near relatives. The Barons' house had ever been a home to him; and while the Colonel was almost as his father, Mrs. Baron filled rather the position of an elder sister. To Roy and Molly, Denham was the most delightful of big elder brothers.

He had seen a good deal of both Polly and Jack in their childhood, but during later years he had been much on service abroad. His first view of Polly Keene, his quondam pet and playmate, transformed into a grown-up young lady, took place a few weeks before this date. Denham had lost his heart to her in the first hour of their renewed acquaintance; and Polly soon discovered that he was the one man in the world who had her happiness in his keeping.

Three or four days later, when good-byes were said, no voice whispered either to him or to Polly how long-drawn a separation lay ahead.

CHAPTER IV

DOLEFUL TIDINGS

"A LETTER from Paris! Grandmother, a letter from Paris!" cried Molly, as she rushed into the dining-room of Mrs. Fairbank's house at Bath. "And it is in my papa's handwriting."

Mrs. Fairbank, a comely elderly lady—in these days, with the same weight of years, she would have been cheerfully middle-aged—adjusted her horn spectacles, tied her loosened capstrings, and scrutinised Molly's eager face.

"You make too much of things, child," she remarked. "Whatever befalls, it is not worth while to discompose yourself."

Then she lifted the letter, examined it, weighed it in either hand—and hesitated. Being an excellent disciplinarian, she was wont to welcome opportunities for the exercise of self-control. Molly, squeezing her hands together, wondered if the slow moments would ever pass, and Polly found it scarcely easier to endure delay.

"Jack!" gasped Molly,—and "O Jack!" echoed Polly, in a tone of relief.

The young man who walked in—he was hardly more than a boy in years—bore small resemblance to his sister. He was of squarer build than Polly, under medium height, and muscular in make; his features were irregular, and the eyes were light blue, instead of brown. Jack Keene boasted no particular pretensions to good looks, but he was very generally liked; and Mrs. Fairbank, after the manner of elderly ladies, doted on her grandson.

Jack read the little scene at a glance, and as he stooped to greet one after another, he said—"News from France, ma'am? And what may they say?"

Having no further excuse for delay, Mrs. Fairbank opened the letter, and took thence a tiny missive, addressed to Molly. "From Roy," she said. "I think—" and there was a dubious pause—"I think I may permit you to read this to yourself, child. Doubtless your mamma has seen it."

Molly fled to the window-seat, and plunged into the delights of Roy's epistle. Mrs. Fairbank's face of growing concern failed to draw her attention; and a murmured consultation which took place might have gone on in China, for all the impression that it made upon her. But having three times gone through the contents of her little sheet, and having kissed it tenderly, she at length carried it to Polly.

"Roy has forgotten to sign his name," she said. "And he said he had a cold, and felt sea-sick."

"Roy, I regret to say, is far from well, my dear," replied Mrs. Fairbank solemnly. "He has been taken ill with a most unexpected disorder. It is truly unfortunate. He has the smallpox. Doubtless he took it into his constitution before ever he left England."

Polly wound her kind arms round the image of childish woe.

"But numbers and numbers of people have smallpox," she observed. "And many get over the complaint." This was lame comfort; but what else could Polly say? The reign of that awful scourge of nations was not yet over. Vaccination had indeed been recently discovered, and was making way; but it had not yet become general, even in England. Many people, from ignorance, doubted its worth; many still preferred the more dangerous safeguard of inoculation. Strange to say, the Barons had not yet, as a family, undergone vaccination, though they had talked of doing so. They had been half sceptical, half dilatory.

"Will his face be all marked?" asked Molly sadly, thinking of the innumerable seamed and disfigured faces which she knew. "Will he be like Mr. Bryce?"

"I hope not, indeed. All who have it are not scarred. Captain Ivor is not, yet he has had it. Think, Molly, is not Captain Ivor kind and brave? He has taken Roy into another house, and he will not let your father or mother go near to Roy, or any one who has not had the disorder. He is nursing Roy himself, and they hope it will not be a severe attack."

Molly was hard to comfort; and no wonder. All her spirit went out of her, and she seemed to care for nothing except clinging to Polly, and being assured again and again that Roy would probably soon be better.

Letters then were not an everyday matter, as now. Posts were slow and expensive, and people thought more than twice before putting pen to paper. Colonel Baron had promised to write again soon, but he waited till he should have something definite to say.

The suspense was almost as hard for Polly as for Molly—harder, perhaps, in some respects. Only, as Ivor had had the disease, and had nursed a friend through it without being the worse, he might be counted safe. But Polly knew that his stay in Paris was likely to be much lengthened. Weeks might pass before Roy would be able to travel. Denham would most likely spend the whole of his leave in attendance upon the boy; and when he returned, he would have no time left to spare for Bath. At present her fears extended no further.

Meanwhile public events marched on with strides. That month of May 1803 was astir with events. The maintenance of peace between England and France became daily more precarious. The feverish ambition of Napoleon could know no rest, so long as he was confronted by a single nation in Europe.

This state of tension increased, till the breaking out of war became merely a question of days. Large numbers of English had seized the rare opportunity of a year free from fighting to travel in France, and at this time there were something like eight or ten thousand British in that country. The French papers heartily assured English travellers of their absolute safety, even supposing that war should break out; and doubtless the editors meant what they said. Few men, French or English, could have foreseen what was coming.

Despite such assurances, a homeward stampede took place; and the thousands were, by some accounts, reduced rapidly to hundreds. Many lingered, however; not all detained, as were the Barons, by illness. War-clouds might threaten; but that travellers should be affected by a declaration of war was a thing unheard-of.

In May, suddenly at the last, though the step had been expected, the British ambassador was recalled from Paris, and the French ambassador was recalled from London. Meanwhile the English Government, issuing letters of marque, seized a number of French vessels which happened then to be lying in English ports. This, it was said, took place before the declaration of war could reach Paris. If so, though the deed was sanctioned by centuries of custom, one must regret its haste. But no excuse can be found for Napoleon's illegal and cruel act of reprisal.

Like a thunder-crash came the order, before the close of May, arresting all peaceable British travellers or residents in France, and rendering them "prisoners of war" or détenus, to be confined in France during the pleasure of the First Consul. The shortened form of that direful proclamation, as it was printed in English newspapers, spread dismay through hundreds of English homes, and awakened a furious burst of anger against the man who had dealt the blow.

CHAPTER V

GENERAL INDIGNATION

"HALLO, Keene!—Mr. Jack Keene! At your service, sir!"

"Admiral! How do you? I was near giving you the go-by."

"Near running me down, you might say. Like to a three-decker in full sail. You are going indoors. Ay, ay, then I'll wait. I'll come another day. 'Twas in my mind that Mrs. Fairbank might be glad of a word. But since you are here—"

"She will be glad, I can assure you. Pray, sir, come in with me. This is a frightful blow. It was told me as I came off the ground after parade, and I hastened hither at full speed."

"Ay, ay, that did you," muttered the Admiral. "Seeing nought ahead of you but the Corsican, I'll be bound."

"Tis a disgrace to his nation," burst out Jack. "Sir, what do you think of the step?"

"Think! The most atrocious, the most abominable piece of work ever heard of. If ever a living man deserved to be strung up at the yard-arm, that man is Napoleon."

"It can never, sure, be carried out."

"Nay, if the Consul chooses, what is to hinder?"

"Government will not give up the vessels seized."

"Give them up! Knuckle down to the Corsican! Crouch before him, like to a whipped hound! Why, war had been declared. Our ambassador had had his orders to come home before ever the step was taken. Give up the ships! Confess ourselves wrong, in a custom which has been allowed for ages! We'll give nothing up—nothing, my dear Jack. Sooner than that, let Boney do his best and his worst. Wants to chase our vessels of war, does he? Ay, so he may, when they turn tail and run away. We shall know how to meet him, afloat, fast enough—no fear! With our jolly tars, and gallant Nelson at their head, there's a thing or two yet to be taught to the First Consul, or I'm greatly in error."

The two speakers stood outside Mrs. Fairbank's house in Bath, where they had arrived from opposite directions at the same moment. Both had walked fast, and each after his own mode showed excitement. The older of the two, Admiral Peirce, a grizzled veteran, made small attempt to hide the wrath which quivered visibly in every fibre of his athletic figure. He had usually a frank and kindly countenance, weather-beaten by many a storm, yet overflowing with geniality. The geniality had forsaken it this morning, and he looked like one whom an enemy might prefer not to meet at close quarters.

Jack Keene had, as he intimated, come straight from parade, not waiting to get rid of his uniform; and in that uniform the young Ensign looked older than in mufti. Also he seemed older in this mood of hot indignation, his light blue eyes sparkling angrily, and his brows frowning. For once, whatever might usually be the case, he had the air of a grown man.

"Tis a freak of Boney's—not like to last. The whole civilised world will cry out upon him. Not that he greatly troubles his pate with what folks may say," added the Admiral, reflecting that the civilised world had been for many years crying out upon Napoleon, with no particular result. "Still, there are limits to everything. Yes, yes, I will come in with you."

Jack led the way, and they found a forlorn trio within. Mrs. Fairbank knitted fast, with frequent droppings of stitches; and Polly, white and dismayed, had an arm round Molly, whom she was trying to comfort, while much needing comfort herself. Two days before, a letter had come from Colonel Baron, with a cheerful report of Roy, and Molly's happiness was sadly dashed by this new complication.

Jack was speedily by their side, doing his best to console them both. Molly, as earlier stated, was small and childish for her twelve years, and Jack was next-door to being her brother; so she cried quietly, leaning her face against his scarlet coat, while he whispered hopeful foretellings.

"This is truly a doleful state of things, ma'am," the Admiral observed, turning his attention, as in duty bound, towards the elder lady. "Who could have thought such wickedness possible? 'Tis prodigiously sad. I vow there was never such a being as this First Consul since first the world was created. But cheer up, ma'am. Never you mind about him, nor pretty Polly neither. Things will all come right in time—maybe sooner, maybe later—there's no sort of doubt."

"But are they indeed all prisoners, sir?" asked Polly.

"Nay, nay, not so bad as that! The First Consul may be but little removed from a fiend; yet even he does not war with women and with schoolboys. Mrs. Baron is free to return when she will, and to bring Roy with her. 'All the English from the ages of eighteen to sixty,' and any such as are in His Majesty's Service—those are the terms of the arrest. Roy being under eighteen, and not yet having a commission, is not included. 'Tis only Colonel Baron and Captain Ivor who are to be accounted prisoners of war. An atrocious deed, with harmless and innocent travellers."

That "only" sounded hard to Polly, though it was meant in all kindness. The Admiral was doing his best to bring a ray of sunshine into a cloudy prospect.

Before any one could reply, the door opened, and in sailed Mrs. Bryce, followed by her husband. They had found their way to Bath, avowedly to drink the waters; and Mrs. Bryce was looking her gayest, as befitted a fashionable visitor to fashionable Bath.

When once Mrs. Bryce was upon the scene, other people had no chance of saying much.

"So this is the outcome of it all!" she exclaimed, with uplifted hands. "A fortnight in Paris—more like to be a matter of years. Nap has 'em in safe keeping, and depend on 't, he'll not let them go in no sort of haste. I protest, when Colonel Baron told me of his purpose, I had an inkling in my mind of what should come to pass. Did I not warn him? Did I not tell him he should be content to stop at home? 'Tis now even as I foretold. If the mice will foolishly run into the trap, with their eyes open, what may be expected but that in the trap they must stay? My dear Mrs. Fairbank, I do most sincerely condole with you all."

Mrs. Fairbank parted her lips, and had time to do no more.

"Tis done now, and it cannot be undone. But 'tis a lesson for the future. Had the Colonel but shown his accustomed good sense, he would have taken warning by my words, and might now be sound and safe in England. But everybody has expected war. If England will not act at the bidding of old Nap, England has to fight. And England will not obey his will. Therefore we must needs fight."

"The Treaty of Amiens—" Mrs. Fairbank began to say.

"O excuse me, I beseech! We agreed, doubtless, in that Treaty, to carry out certain conditions, if old Nap should carry out certain others. And on his part those conditions have been broken. For months the Treaty has been worth so much waste paper. Since Boney has not kept his share of the agreement, we are free. What! are we to yield to the tyrant, and to do his will? I protest, England is not yet sunk so low."

The others tried to intimate how fully they agreed with the lively speaker, but she went on, unheeding—

"I have it all from my brother, who has it at first-hand from His Grace the Duke of Hamilton. I venture to think that's unimpeachable, ma'am. One thing is sure, our friends over the Channel will not be back this great while. I give them at the least three years. Nay, why not four or five?"

"Nay, why not forty or fifty?" drily asked Jack. "Nay, Molly!" —as he felt her start. "Who knows? The war may last but six months. And Roy is free."

But he could not speak of Ivor as free: and he saw Polly's colour deepen, her eyes filling. This could not be allowed to go on. A diversion had become necessary: and Jack's voice was heard to say something in slow insistent tones, making itself audible through Mrs. Bryce's continued outpour.

"A very great friend of his Grace—" reached her ears. Mrs. Bryce, being much of a tuft-hunter, stopped short.

CHAPTER VI

THE DUKE'S PARTICULAR FRIEND

"You were saying, Jack— What was that which you were pleased to remark?"

"I did but observe, ma'am, that the Duke of Hamilton's most particular friend—who is also, in my humble opinion, and in that of many others, the greatest of living Englishmen—chances to be at this instant staying in Bath."

"The Duke's particular friend! Then, sure, 'tis somebody whom we are acquainted with, my dear—" turning to her husband, more impressed with the fact of the ducal friendship than with Jack's estimate of the man. "Somebody, doubtless, in the world of mode; and 'twould be vastly odd if we had not come across him."

"We may scarce claim to be acquainted with all his Grace's friends," mildly objected Mr. Bryce.

"Well, that's as may be. But who is the distinguished person, Jack?"

"None less than General Moore himself, ma'am."

Mrs. Bryce held up startled hands, and vowed that the most ardent wish of her heart was to set eyes on this Hero of heroes, whom by a succession of mischances she had hitherto failed to meet.

"Though in truth 'tis small marvel, since the General is for ever away across seas, fighting his country's battles," she added. "Excepting in this past year of the peace, when each time that I would have seen him, fate prevented me. And he is in Bath at this moment, say you?"

"Ay, ma'am. And if you desire to find another who reckons General Moore to be the foremost British soldier of his day, and to be the noblest among men,—why, I've but to refer you to Ivor."

"And now I bethink myself," exclaimed Mrs. Bryce. "Was not that a Mrs. Moore to whom in the Pump Room yesterday Mrs. Peirce introduced me, saying I should feel myself honoured, knowing her son's name? I protest, I had forgot the matter till now, having had my attention drawn off, and not bethinking me of General Moore."

Mr. Bryce intimated that his wife was in the right. He had imagined that Mrs. Bryce understood. General Moore's mother was the widow of a very able Scots physician, as he proceeded to explain.

"A woman of much force of character and no small charm of manner," he said. "The General, 'tis reported, has been ever distractedly fond of his mother and sister, and they are here together for a spell. I fear 'tis likely to be a brief spell. War being now declared, his services will be assuredly needed elsewhere."

The attention of Mrs. Bryce was as effectively diverted as Jack had wished. "The General's mother—and friends of his Grace of Hamilton," she meditated aloud. "A most unassuming person! But since I'm introduced, I'll most certainly leave upon them my visiting-ticket."

"By all means, my dear, if you so desire. 'Tis said that the good lady cares not greatly for society; ne'ertheless, she'll doubtless take it well, in compliment to her son's merits and his great fame."

"It may be we shall see them again in the Pump Room, on leaving this. I'll away thither at once. Could I but set eyes on the General, 'twould be the utmost gratification to me that ever I felt." She stood up, eager to be off; but as she went she gave a parting fling—"Depend on 't, old Nap will be in no sort of hurry to let his prisoners go free. No one need think it."

On that particular day Mrs. Bryce had not her wish; yet the fulfilment of it was not to be long delayed.

A morning or two later what she desired came unexpectedly, as is often the case. She had taken Molly for a walk, and Mr. Bryce had left them outside the Pump Room, to go to a shop. "I shall be speedily back, my dear," he had said. "If you choose to wait for me, I will rejoin you."

Mrs. Bryce elected to wait, and hardly had he vanished round a corner before her eyes fell upon two men, coming out of the Pump Room in earnest talk. The younger of the pair was unnoticed by Mrs. Bryce. All her attention was instantly concentrated on the other. She was quick of wits and keen in observation, and she had heard more than one description of Moore's personal appearance.

A consciousness flashed across her, as she noted the splendidly borne head, that here was no ordinary individual.

Could it be—? Might it be—? Mrs. Bryce glanced round in despair for her husband. He was out of sight. That she should be foiled again was not to be endured.

Shyness had never been a characteristic of Mrs. Bryce. If this indeed were the man whom she craved to see, she would not miss her opportunity.

The two came to a pause, and Mrs. Bryce drew nearer, Molly keeping close by her side. In a clear full voice one was speaking—the one who absorbed Mrs. Bryce's attention,—and the concluding words of the short sentence were uttered with an intonation which, to any one who had heard Moore speak before, must have been unmistakable—

"If ever a man tells me a lie—" then came a slight impressive break,—"I've done with him!"

Something in a lower tone from the other, and a response—

"Ay, no need to assure you of that. I shall see you soon again."

He lifted his hat, and as they parted, going different ways, Mrs. Bryce with a swift movement placed herself in the path of the General. His hat was again courteously raised, and the penetrating eyes met hers.

"Pray, sir—I entreat of you—pardon my boldness. I have not yet the supreme honour of your acquaintance. But, if I am not strangely in error, your name, sir, is—"

"John Moore, madam."

Mrs. Bryce sank to the ground in a profound reverence, and Molly dipped a neat little curtsey in her wake.

"Sir, it is the proudest moment of my life. That I should be vouchsafed the distinction of speaking with our most famous General! But excuse my boldness, sir. You are acquainted with my young friends, Captain Ivor and Mr. Jack Keene. And my husband, Mr. Bryce, has had the honour of a word with you. I have hitherto been less fortunate, though I too have been introduced to your excellent mother, Mrs. Moore, upon whom I have taken the liberty of calling."

The enthusiastic lady failed to realise that, while to her he was one of the foremost men living, she to him was no more than an unknown item in a population of seventeen millions. General Moore listened with most polite gravity, but the glimmer of an amused smile struggling for the mastery might have been detected.

"Sir, if you would graciously permit me to shake hands with one to whom my country owes a heavy debt of gratitude—"

The luminous smile broke into open sunshine. Handshaking was not then so common as it is now between slight acquaintances, but as a matter of course his hand was at once held out.

"You honour me greatly, madam, and I am sincerely grateful. But I fear you overestimate my services. I have but sought to do my duty."

Mrs. Bryce curtseyed profoundly again.

"I may not venture to detain you, sir. You are doubtless much occupied. But none can fail to know that General Moore has fought more often and more gallantly for his country than any other general of our day. I thank you most gratefully, sir, for the honour you have done me."

"On the contrary, ma'am, 'tis I who am honoured by your kind attention."

"Nay, sir, nay, that is but a fiction of speech. I shall never, sir, to my dying day be oblivious of this hour. And truly I hope that I have not seen General Moore for the last time."

Mrs. Bryce trod upon air the rest of the morning.

CHAPTER VII

PRISONERS OF WAR

COLONEL BARON might not confess the fact in so many words, but before he had been three days in Paris he sorely regretted his own action in taking Roy across the Channel.

When Roy was first taken ill—after ailing for a day or two—the doctor, hastily called in, at once pronounced him to be probably sickening for that fell disease which for centuries had held the world in a thraldom of terror. Not without reason. Up to the close of the eighteenth century nearly half a million of people had died in Europe every year of smallpox.

Mrs. Baron was a fond and tender mother, yet when first that dread word left the doctor's lips, even she fled in horror from the sick-room. From infancy she had been used to admiration, and she knew too well to what a mockery of the human face many a lovelier countenance than hers was reduced.

Soon, ashamed of herself, she rallied, and would have returned; but this the Colonel sternly prohibited.

The people of the hotel, in sheer dismay, insisted on Roy's instant removal. The question was—where could he go? Then it was that Ivor came to the rescue, He had had smallpox. He was not only safe, but also experienced, having nursed a friend through the complaint. He would take charge of the boy himself, allowing none other to enter the room. His steady manner and cheerful face brought comfort to everybody.

Consulting with the hotel people, he heard of a M. and Mme. de Bertrand living near, who might be willing to receive him and Roy. They and their servant had been inoculated, and were safe. Since they were members of the old lesser noblesse, and had lost heavily in Revolution times, they might be glad thus to make a little money.

The matter was speedily arranged, and Roy was conveyed thither wrapped in blankets, already much too ill to care what might be done with him. Colonel and Mrs. Baron remained at the hotel, to endure a long agony of suspense.

As days passed, it appeared that no one else had caught the disease, and Roy was found to have it mildly. It was not a case of the awful "confluent" smallpox, but of the simple "discrete" kind. There was a good deal of fever, and at times he wandered, calling for "Molly," but more often he was dull and stupefied, saying little.

Perhaps nobody who had seen Denham Ivor only in society or on parade would have singled him out as likely to be a good nurse. A modern trained nurse would have found much to complain of in his methods, and not a little to arouse her laughter. Many of his arrangements were highly masculine: the room was never in order; and whatever he used he commonly plumped down in the most unlikely places.

But his patience and attention never failed; he never forgot essentials; he never seemed to think of himself or to require rest. Day after day he stayed in that upstairs room, only once in the twenty-four hours going out for a short walk, that he might report Roy's condition to Colonel Baron, meeting the latter, and standing a few yards from him. If Roy was able to get a short sleep, Denham used that opportunity to do the same; but in some mysterious way he always contrived to be awake before Roy. His handsome bronzed face grew less bronzed with the confinement and lack of exercise.

No one beside himself and the doctor entered the room, except a wizened old Frenchwoman, herself frightful from the same dire disease, who was hired to come in each morning, while Ivor was out, that she might put things straight.

Then tokens of improvement began, and Colonel Baron sent a letter home which cheered Molly's heart. But later violent inflammation of one ear set in. For days and nights the boy suffered tortures, and sleep was impossible for him or for his attendant. Roy in his weakness sometimes cried bitterly with the pain, always begging that Molly might never be told. "She'd think me so girlish," he said, while tears rolled down his thin cheeks, marked by half a dozen red pits.

In the midst of this trouble, a terrible blow fell upon Ivor, in the shape of a stern official notice, desiring him to consider himself a prisoner of war, and at once to render his parole.

Ivor was commonly a calm-mannered man, with that quietness which means the determined holding down of a far from placid nature. Some words of fierce wrath broke from him that day. He was compelled to go and give his parole, infection or no infection; and indignant utterances were exchanged between him and Colonel Baron, whom he chanced to meet on the same errand. Then he had to hasten back to the boy, with a heavy weight at his heart.

It meant to Ivor, not only indefinite separation from Polly, but also a complete deadlock in his military career.

He was passionately attached to Polly. He was not less ardently attached to his Chief. If one half of his spare thoughts was given to a future with Polly for his wife, the other half was given to a future of campaigning under Moore.

Had imprisonment come in the ordinary way, through reverse or capture in actual warfare, he would have borne it more easily. The sense of injustice rankled. He foresaw, too, the complications likely to arise, and the possibility of long delay in the exchange of prisoners. As he patiently tended the boy, his brain went round at the thought of his position, and that of Colonel Baron.

Three or four more days of strain, and then the abscess in the ear broke, causing speedy relief. The first thing Roy did was to fall into a profound sleep. When he woke up, feeling much better, his murmur was as usual for "Den!" No answer came.

He took a look round. The light from the window was growing dim, and the pain in his ear had vanished. Denham, near at hand, was leaning back in the only pretence at an easy-chair which the room held. His head rested against the wall, and he seemed to be heavily asleep.

Boys of twelve are not always very thoughtful about other people, but an odd feeling came over Roy, as he noted the fine-looking young soldier in that attitude of utter weariness. Through his illness he had actually never once seen Ivor asleep till now.

"He must be tired, I'm sure. But I wish he'd wake."

The door opened slowly, and Roy's eyes grew round with surprise. Nobody entered this infected place, as he knew, except Ivor, the doctor, and the old woman. This newcomer stepped quietly up to the bed. She was quite a girl, perhaps two or three years older than Polly. She was very slight, with a neatly-fitting dress. The lighted candle in her hand threw a glow upon her face. It was a sweet face, delicate and gentle, and it would have been exceedingly pretty but for the evident ravages of a long-past attack of smallpox. There were no "pits" on her skin, but a certain soft roughness marked the whole, as if it had once been closely covered with pits. The face was pale, its features were even, short black hair curled over a wide forehead, and the dark eyes were full of sadness.

Roy put out his hand involuntarily, only to snatch it back.

"I forgot. Den told me I must not touch anybody except him—not even that ugly old woman. I'm so thirsty. I wish he'd wake up."

"Pauvre enfant!" She went to the table and brought a glass of milk, which Roy drank eagerly. Then she smoothed his bedclothes.

"But you ought not, you know," observed Roy's weak voice. "You might catch the smallpox. Den would make you go. Can you talk English?"

"Yes, I can talk English." She said the words in foreign style, with slow distinctness, but with a pure intonation. "I learnt English in your country. Yes, I have been there for three or four years. Monsieur votre frère—your brother—il a l'air très fatigué."

"Den isn't really my brother, only he's just like one. He's just Den, you know—Captain Denham Ivor, of His Majesty's Guards. He hasn't been to sleep for ever so long, and that's why he is tired. My ear has been awfully bad, for days and days. And Den was always here."

The girl left Roy, and went closer to the sleeping man. He remained motionless, the eyes closed, a slight dew of exhaustion on the brow, the face extremely pale. She sheltered the light from his eyes with her hand, and, turning away, began putting things straight. A few touches altered wondrously the look of the whole room. Roy lay and watched her.

"What's your name?" he asked. "Are you M. de Bertrand's daughter? I'm deaf still, so don't whisper."

"No. I am Lucille de St. Roques." She came near, not to have to raise her voice, and Roy again shrank from her. "It does not matter. I have had the complaint, and I do not fear."

"I wonder where your home is."

"Ah,—for that, I have not now a true home. Cependant, I have kind friends at Verdun, where I live. I am but just come here—unexpected."

"And have you a father and mother in that place—Ver—something?" Little dreamt Roy how familiar a name it would become in a few months!

"Verdun. My father and mother they were of the old noblesse, and—hélas!—thirteen years ago, in the Revolution, they were guillotined."

"O I say, how horrid!" exclaimed Roy. "Why, you must have been quite a little thing!"

"I was not yet eight years old. I was in prison with them, many many weeks, before they went out to die."

Ivor woke suddenly and stood up, leaning against the solid four-poster, since the room went round with him. He saw a girlish figure, and vaguely felt that she had no business there.

"Do not make so great haste. Will you not rest a little longer?" a kind voice said, and a soft hand came on his wrist.

"But indeed, mademoiselle, you must go away at once," he urged earnestly. "It is smallpox. Pray, go. You will take the infection."

"But me, I do not intend to go," she replied cheerfully, with her pretty foreign accent. "You need not be afraid for me, monsieur. See—I have had it. I am not in danger—not at all. You are fatigué—n'est-ce pas? It has been a long nursing—yes, so I have heard. When did you take food last?"

Denham confessed that he had not eaten for some time; he had not been hungry. Well, perhaps he was a trifle fatigué; but 'twas nothing—nothing at all. He was ready now for anything. If mademoiselle would only not put herself in danger! By way of showing his readiness, he made a movement forward; but he was forced to sit hastily down, resting his forehead on his hand. The long strain had told upon even his vigorous constitution.

"Ah!—C'est ca!" she murmured. "But you will be the better, monsieur, for a cup of coffee."

Ivor had no choice but to yield, and she moved daintily about, making such coffee as only a Frenchwoman can, and bringing it presently to his side.

"This is not right," he protested. "I cannot allow you to wait upon me, mademoiselle!"

She would listen to no remonstrances, however; and when he had disposed of it, she insisted that he should lie down on a couch in the small adjoining room, while she undertook to look after Roy. She had her friends' permission, she said, not explaining that she had refused to be forbidden; and monsieur in his present state could do no more. How long was it since he had slept? Ah, doubtless some days!

Ivor gave in, after much resistance, and in ten minutes he was again heavily asleep. Nature at last claimed her due.

When he woke, after several hours' unbroken rest, he was another man. Roy seemed much better; the doctor had paid a visit, and was gone; the room could scarcely be recognised as the same; and Ivor warmly expressed his gratitude, wondering as he did so at Lucille's look of steady sadness. She insisted on coming the next day, that he might rest and have an hour's walk.

"Isn't she jolly?" exclaimed Roy, when the door closed behind her. "She has told me lots of things while you were asleep. Only think, her father and mother were both guillotined! Both of them had their heads cut off. And they hadn't done one single thing to make them deserve it. They were awfully good and kind to everybody, she says. And she was only a little girl then; and when they were dead, somebody took her away to England, and she was there three or four years. And then she came back to France, and she lives with some people at a place called Verdun. She says they give her a home, and she works for them. And she would like to go to England again some day."

But Lucille de St. Roques had not told Roy her more recent sorrow. She let it out to Captain Ivor a day or two later. Only one year before this date she had become engaged to young Théodore de Bertrand, son of the old couple downstairs, and three months later he had been drawn for the conscription. No use to plead that he was practically an only son, since the second son, Jacques, was a ne'er-do-weel, who had taken himself off nobody knew whither. More soldiers were wanted by the First Consul for his schemes of foreign conquest, and young De Bertrand had to go. Scarcely four months after his departure news came that he had been shot in a sortie in the Low Countries. Large tears filled Lucille's eyes, and dropped slowly.

"Ah! So many more!" she said. "Thousands—thousands—called upon to be slain for nothing! Not for their country, but for the ambition of one bad man. It makes no difference, monsieur, that they love not the usurper. My Théodore was of the Royalist party, yet he had to go. And the poor old father and mother—they are left without one son in their old age!"

CHAPTER VIII

THE THREATENED INVASION

THERE is a good deal of variety in the different accounts as to the number of British subjects who actually suffered arrest in French dominions on the breaking out of the war. Some estimates amount to as high a figure as ten thousand; but these seem to have made no allowance for the rapid homeward rush just at the last. Other estimates give only a few hundreds, belonging chiefly to the upper ranks of society.

But indeed all classes were included. Not only officers in the Army and Navy, but lawyers, doctors, clergymen, men of rank, men of business, artisans, English residents abroad, all alike had the notice of arrest served upon them. All alike were either thrown into prison, or, if gentlemen, were ordered immediately to constitute themselves prisoners of war upon parole, with the alternative of becoming prisoners of war in strict confinement.

The mass of those détenus who were allowed to be upon their parole had to go to Fontainebleau; and thither Colonel and Mrs. Baron betook themselves. On the score of danger to others from infection, a slight delay was permitted to Ivor, still in charge of Roy.

The question had at once arisen whether Mrs. Baron should not be sent to England with her boy as soon as he should be fit to travel. Women were, at least in theory, free to go where they would, provided only that they could obtain passports. But Mrs. Baron refused to consider any such proposal. She could not and would not be separated from her husband. "Of course I shall go with him to Fontainebleau," she said decisively. "It cannot be for long. Roy must come to us there. It only means leaving his schooling for a quarter of a year. He will not be strong enough for work at present; and something is sure to be arranged soon. Then we shall all go home together."

The general opinion among friends in England was that Roy would certainly be sent across the Channel so soon as possible. Yet there were some who doubted. Mrs. Baron was known to be a mother perhaps more fond than wise; and it seemed conceivable that she might decline to part with him.

This unlooked-for move of Napoleon's caused a burning outburst of indignation throughout the length and breadth of England; and newspapers vied one with another in wrathful condemnation of his "unmannerly violation of the laws of hospitality."

War once begun was carried on with energy by both the British and the French. As a first step, Napoleon did his best to damage English commerce by closing Continental markets against her—supremely careless of the suffering which he inflicted on his own friends and subjects. But at this particular game England was the better of the two.

Ironclads were then unknown; and though the great three-deckers, with their seventy or a hundred guns apiece, could not be built in a day, yet war-vessels were of every description, from three-deckers down to merchant-ships, hastily fitted with a few guns, and sent forth to do their best. In a short time Great Britain had about five hundred war-vessels, with which she swept the seas, recaptured such Colonies as had been yielded to France by the Treaty of Amiens, blockaded harbours in countries subject to the First Consul, and made descents upon their ports, carrying off prizes in the very teeth of French guns and fortifications.

Napoleon's next move was definitely to announce his intention of invading England, of conquering the country, and of making it into a Province of France.

This was a feat more easily talked of than accomplished. Preparations, however, were pushed forward on a great scale. Huge flotillas of flat-bottomed boats, to act as transport for the invading army, were collected at various places, more especially at Boulogne; and at the latter spot a camp was formed of between one and two hundred thousand soldiers, to be in readiness for the moment of action. Also a strong fleet of French men-of-war was being prepared, to convoy the transports across the Channel.

Though no true-hearted Englishman believed for a moment in the possibility of his country becoming a French Province, all knew that the threatened invasion might take place.

An extraordinary burst of enthusiasm, throughout the whole country, was the immediate response to Napoleon's threat.

Large supplies of money were freely voted and given. The regular Army was increased, and the Militia was called out; while a Volunteer force sprang into being with such rapidity that it soon numbered about four hundred thousand men.

These citizen-soldiers, as it was the fashion to call them, were scattered all over the country, each place having its own corps. But the regular troops, drawn from various parts, were chiefly stationed where the danger seemed to be the more pressing, between London and the south coast—Sir David Dundas being in command.

Along the shores were erected batteries and martello towers—many of which remain to this day. And since Boulogne was the headquarters of the French army of invasion, an advanced corps was placed on the opposite coast, near Sandgate, under General Moore, in readiness to repel the first onslaught.

There Moore occupied his time in such splendid training of the regiments under his control, that throughout the long years of the Peninsular War, after he himself had passed away, the stamp of his spirit rested upon them, the impress of his enthusiasm and of his magnificent discipline made them the foremost soldiers in the British Army. Among these were the regiments which, as "The Reserve," bore the brunt of the fighting in Moore's famous "Retreat," and which were known in Spain and at Waterloo as Wellington's invincible "Light Brigade." Wellington used those regiments for the saving of Europe; but Moore made and tempered the weapon which was to be wielded by Wellington.

To the delight of Jack Keene, an opportunity offered itself whereby he might effect an exchange into one of the Shorncliffe regiments.