Anthony Cragg's Tenant

Agnes Giberne

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

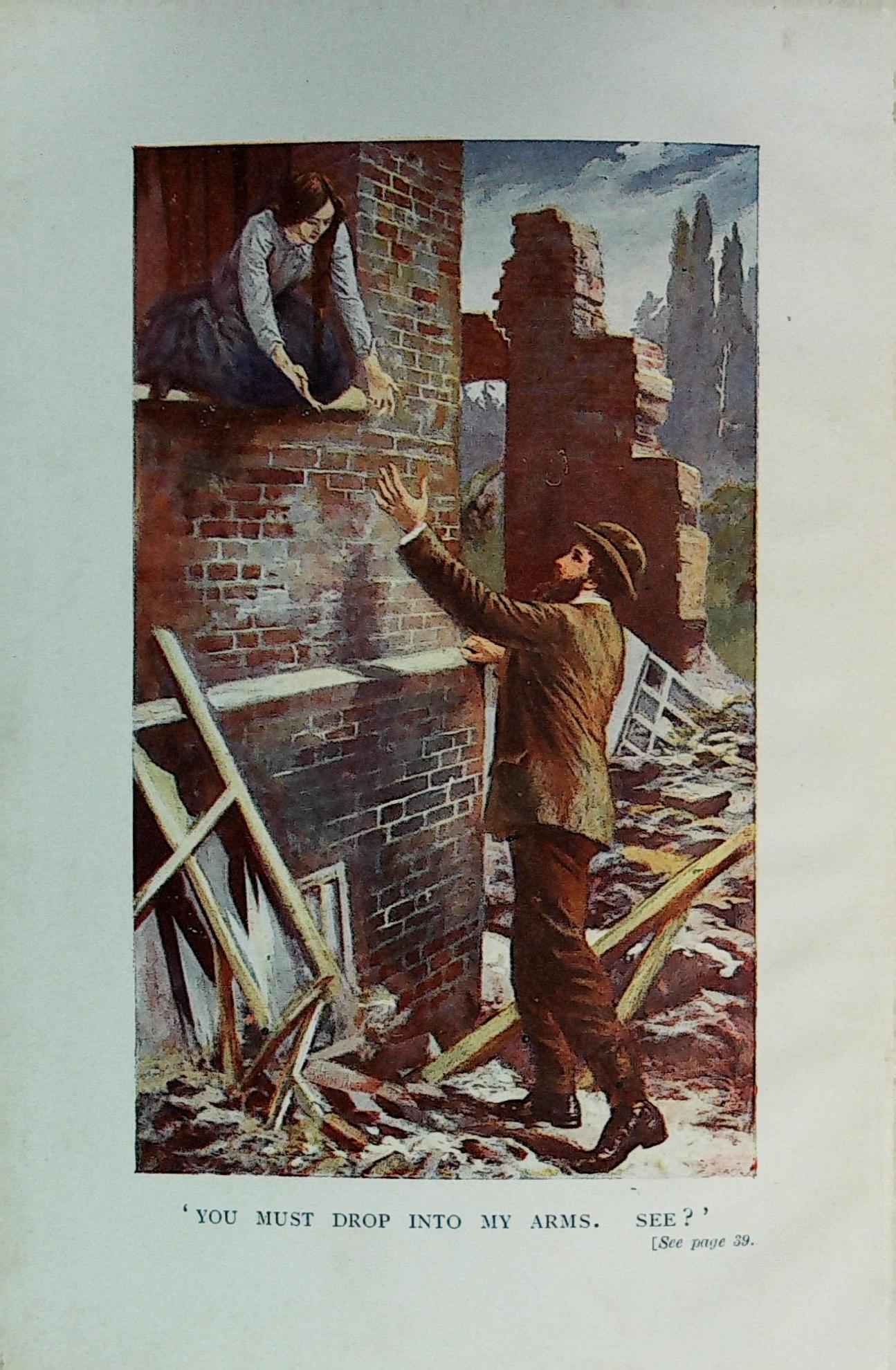

"YOU MUST DROP INTO MY ARMS. SEE?"

ANTHONY CRAGG'S

TENANT

BY

AGNES GIBERNE

AUTHOR OF

"GWENDOLINE," "THROUGH THE LINN," ETC.

WITH COLOURED ILLUSTRATIONS BY

LANCELOT SPEED

LONDON

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

4 BOUVERIE STREET, and 65 ST. PAUL'S CHURCHYARD

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

I. First Appearance of Mr. Dale

II. An Unlooked-For Collapse

III. Mrs. Anthony Cragg

IV. A Rescue

V. Alone in the Wide World

VI. The Next Step

VII. Into a New Home

VIII. A Search Unauthorised

IX. What Mr. Peterson Had Said

X. Dot's Opinion

XI. In the Very Act

XII. Those Three Letters

XIII. What Had Gone Wrong

XIV. Little Dot—A Catastrophe

XV. A Heavy Fall

XVI. The Course of Events

XVII. A Secret Made Known

XVIII. A Dire Mistake

XIX. A Very Narrow Escape

XX. Made Clear

ANTHONY CRAGG'S TENANT

CHAPTER I

First Appearance

of Mr. Dale

"ANTHONY! I say, Anthony! you're wanted. Make haste, will you? Folks can't dawdle round the whole day while you're pottering about upstairs. What are you doing? Do you mean to come, or not?"

"All right, my dear," a man's voice said in the distance, not exerting itself.

Mrs. Cragg tapped her smart parasol on the dusty floor. Although her words held a commanding sound, she was addressing her husband, and not a shop-boy. Mr. Cragg's better half had a reputation for smartness of tongue.

Generally she liked to make her exit at the private door, from which business was excluded; but for once she had gone round by the warehouse, and had travelled down by the uncarpeted wooden staircase at the back of the shop, to a door which led into a side street. At this door she had stumbled on two people, waiting patiently for attention—a tall man, wearing a shabby coat, and a girl.

Shabby people were objectionable in Mrs. Cragg's eyes. She counted herself a fine lady, and loved gay clothes, which she looked upon as a mark of gentility. Mrs. Cragg was not the first person in the world to fall into that mistake.

At this moment she wore a gown of bright blue, while a large scarlet wing stood forth aggressively in her green straw hat. She had a high colour, beady black eyes, a profuse fringe of yellowish hair, and marked features. Not everybody would admire this combination, but Mrs. Cragg was wont to feel satisfied on looking into her mirror.

Six years earlier, when she had figured as the only and hard-worked daughter of a third—rate and unsuccessful country attorney, with a sickly wife and several boys, she had been rather a pretty girl. But then she had worn no fuzzy fringe, nor had she dressed in blue and green and scarlet, nor had she rattled and laughed in self-important tones. These new developments had taken her husband by surprise, and he was not yet used to the change.

"You needn't expect me to stop here, if you mean to be a whole week getting from the top to the bottom of the stairs!" she cried. "I've got something else to see to."

"There's no need. If you'll just ask the gentleman to step inside—"

"We can wait where we are. You need not trouble yourself. Perhaps we have come to the wrong door?" suggested the tall man. "I daresay we ought to have gone to the front entrance in High Street."

"It don't matter. May as well stop, now you are here," said Mrs. Cragg. "He'll be down directly. He's always slow. That's his way."

She had meant to go out this side to save time, but, on second thoughts, she turned back and met her husband.

"Well, I hope you've been long enough," was her greeting. "It's somebody after that new house of yours; and if I was you I wouldn't have anything to do with him. He's as shabby as shabby. Got on a coat that shines like anything, and a pair of gloves that our cook wouldn't look at. And I should think his trousers was made at a slop-shop. If you let him have that house, you won't get any rent for it."

"It isn't always the finest-dressed folks that pay their bills the quickest," replied Cragg, with a wisdom born of experience.

"He won't. You see if I'm not right." Mrs. Cragg liked to be always in the right, and seldom admitted that she was not. Having once committed herself to this particular view of the question, she was certain not to regard the tall man in future with favourable eyes. Cragg knew this, but he said nothing.

"You see!" repeated Mrs. Cragg, "I know a man that can't be depended on when I come across him. He's as poor as a church-mouse, and he wants to get a house rent-free. If you take my advice, you'll pack him off in a hurry."

Cragg was not in the habit of taking a woman's advice in matters of business, though he obtained plenty of it, gratis, from his wife. Her opinion, given lavishly and unasked on all occasions, lost value from its abundance.

Mrs. Cragg passed on, and Mr. Cragg finished the descent of the stairs, with the air of a man who prided himself on being never in a hurry.

"Good morning. This way, please," he said, and he led the strangers to a room behind the warehouse.

Cragg was a vendor of new and secondhand furniture, and indeed of everything required in house-plenishing. The main warehouse, or shop, which opened on the High Street, was full of furniture of all kinds, piled together, with lanes amid the piles. This lesser room in its rear held rolls of carpets and heaps of rugs. One chair stood in the middle, and upon it the newcomer slowly lowered himself, with a sigh of relief, as if he had had enough walking. The girl leant against him, drooping her head, as she had done all along, so that the wide-brimmed hat hid her face. From her height Cragg supposed her to be about thirteen years old, but he did not pay much attention to that matter.

With a business-like air of expectancy he stood waiting. He was much older than his wife, nearer fifty than forty, while she was still under thirty. He had a sensible face, with horizontal lines of care on the forehead, and absent eyes. People talking to Mr. Cragg often fancied that his thoughts were elsewhere; yet he generally heard what was said.

"I am a stranger in Putworth," was the first remark. "My name is Dale; and I am told that you have a house to let."

"Yes. About the only vacant house just now in Putworth."

"So I hear. One that you have just built. I went to the postmaster, and he advised me to come to you. My daughter and I arrived yesterday afternoon. We want to find a quiet home, somewhere on this line of rail. Easier to move my furniture than if we go elsewhere. I may want one or two things from you—possibly"—glancing round—"though we have nearly enough; very nearly enough."

"Putworth is a healthy place. You have not seen the house yet, of course?"

"The outside of it. We walked round yesterday evening for a look. Too late to do anything. It seemed to be just what I want."

"Extremely well situated."

"Well, yes. That meadow in front looks damp, and the surroundings are not pretty. Still, one can't have everything."

"Not pretty!" Cragg bristled up in a mild fashion. "There's green grass and a stream of water. What more can you want? And the meadow's drained."

Mr. Dale did not enlarge on his desires. A faint smile worked its way to his lips. He merely said: "What rent?"

Cragg looked him over carefully. He wanted a good rent, but also he wanted not to lose a tenant. Not that he was by nature grasping; but business was slack in Putworth, and Cragg had an extravagant wife. Her extravagant ways had grown upon her gradually, and Cragg had hardly yet begun trying to check her. Yet he knew that there was need, for embarrassments were increasing upon him, unknown to his friends. At the same time he had a stronger motive to make money and to save than ever in past years.

This motive was consideration for his daughter rather than his wife. He had not ceased to feel affection for his wife, though he found her a growing trial; but his very heart-strings were wound around the child. Each moment that he could spare from business was devoted to Dot.

The building of a new house had been a sudden notion, no long time back, awakened by the sight of a slip of waste land, outside the town, put up for sale. The price asked had been merely nominal,— "dirt-cheap," he said to himself, though not to the seller,—and having a passion for bricks and mortar, he had been unable to resist the temptation; even though that passion had already landed him in difficulties. It was by no means the first speculation of the kind on which he had ventured.

Bricks and mortar are expensive, no matter how cheaply they may be put together. Now that the house was ready for an occupant, even to the extent of being painted and papered, which some said he should have delayed till he had found a tenant, he was naturally anxious to get it off his hands as early as might be.

"Depends on the length of lease," he made answer cautiously.

"I don't want a lease. I want a house by the year,—yours, if it suits. Not much doubt that it will. I have had a lot of trouble, and I want a quiet corner to rest in. May as well say at once that I can't give more than twenty pounds. That's enough for a poor man to pay. Will it do?"

Cragg knew that he was not likely to obtain a larger sum. The house had been run up very cheaply, and it lacked modern conveniences. He had recently let another house, of very much the same size, only in a prettier position, for eighteen pounds; but that was on a lease. Twenty pounds for this, taken by the year, would be as much as he had any right to demand. Yet, with the instincts of a business man, he hesitated. It would not do to snatch at the proposal.

"Perhaps you would like to come and see the place."

"Yes, I should. But I must know your terms first. We don't want a long trudge for nothing, do we, Pattie?"

The girl lifted her face in response, and a thrill of surprise shot through Cragg, seasoned though he was in varieties of faces. Hers was not a common countenance. It could hardly be called beautiful in the full sense, but it was full of goodness and purity; the features were small and colourless; the eyes were of a deep and wistful blue; the sensitive lips were sad. She looked older than Cragg had expected.

"Do we, Pattie?" repeated her father; and she said softly:

"No, daddy."

"So if you want more than that, we'll give up at once, and go elsewhere. I've been doubting between this and the next village."

"Well—I don't know—" began Cragg.

Then he stopped. Those blue eyes came to his, full of a nameless beseeching sorrow, and a faint flush of unshed tears passed over them. Cragg's business instincts went down before a stronger impulse of fatherly pity. Pattie's look made him think of Dot.

"Yes, that will do. Twenty pounds, taken by the year."

"Oh, thank you," breathed Pattie; "I'm so glad."

Then they started for the house, which was a good twenty minutes' walk distant. Cragg's suggestion of a cab was negatived. There was no need, Mr. Dale said; they would enjoy the walk.

Tokens of enjoyment were few; but they managed to get along, though at a lagging pace. Mr. Dale talked fitfully, remarking how the town was grown since his boyhood. Mr. Cragg observed that he could not recall any one of the name of Dale. Mr. Dale said, "No,"—he had been for three years at the big boys' school, and he would not be known to the inhabitants, unless by the former owner of the "tuck shop."

The house stood forlornly alone upon a patch of rough ground, which might in the course of time grow into a garden. At present it lacked soil, plants, and shrubs; in fact, it was no more than a stony little enclosure, surrounding an ugly small house. There were two rooms on the ground floor, with a kitchen behind, and three rooms overhead.

"Precisely the right size," Mr. Dale said.

Flat fields lay on one side, and on the other, beyond a space of untilled earth, lay a stiff row of red cottages. In front flowed a muddy stream, with flags along its edge, and behind were six or seven prim Lombardy poplars.

Mr. Dale was resolute in refusing to undertake "outside repairs," and for a minute Cragg felt disposed to show fight. But again those eyes came beseechingly to his; again he thought of Dot; and again he was vanquished,—he could not have told why.

The whole affair was quickly settled, and Mr. Dale strolled back to the inn with his daughter, Cragg going ahead at a brisker pace.

"That's a nice man, Pattie. A good sort of man, I'm sure. One is glad to have a pleasant landlord. It was quite an instinct that brought me here, wanting to see again the place where I was at school. All schoolboys are not happy, I suppose; but I was—happier than I have been since. Cheer up, little girl. We shall get on all right—now— I don't doubt."

A slight sob shook the girl's slender frame, but she allowed no sound of it to escape, and when she looked up there was a smile on her lips.

"Mr. Peterson won't be likely to find us out in Putworth, daddy."

"No, child, no."

"He won't think of looking for us in such a place."

"No, no, of course not. Why should he?"

"And since you've grown your little beard, you do look so different. I wish you needn't. I like you to look as you used. But even if Mr. Peterson did see you, I shouldn't think he would know you."

"We needn't talk about Mr. Peterson, Pattie. We'll try to forget all that."

"Only, I do wonder sometimes why he should be unkind to a nice dear daddy like you."

"People have their reasons for action, my dear; and one can't expect always to understand. So many mistakes, you know, and harsh judgments. But the comfort is that my Pattie knows her old father."

"I should think I did!" Two tears fell.

"And now we have to consider what to do. A good many things to be seen to—and the house cannot be ready to take us in till—how long did he say? A week was it? I must have another talk with Mr. Cragg, and settle all minor points. But we will go back to the farm for a week. You can write and tell them so; tell them to expect us to-morrow. Dear me, I like that man, Cragg, very much. Shouldn't wonder if he would help us to find a servant; some nice respectable body, who will do for us."

"If only we could have kept Susan! She would have liked so much to come."

"No, my dear." Mr. Dale spoke nervously. "I think we arranged all that."

CHAPTER II

An Unlooked-For

Collapse

MR. DALE stood in the doorway of his new home, looking out.

He and Pattie had arrived nearly a week before, and already the house was in pretty fair order.

Furniture was not too abundant, and he had shown himself unwilling to make many purchases, even though Cragg named the lowest possible prices for things that really could not be done without. Over each one Mr. Dale had mused dubiously; and over each, when he gave in, he did so with a sigh.

A girl had been found for them by Mr. Cragg; clumsy and slow and dull, it is true, but good-tempered; and Pattie toiled like a horse to make up deficiencies.

Such carpets as they possessed were squares, needing only to be laid down on well-scoured boards; and old curtains fitted the windows, almost without alteration. Mr. Dale had given fitful help, but he was not a handy man; and most of the things that he did had to be undone and done again by Pattie, when he was out of sight.

He was tired now, even with the exertion of doing so little; and he made his way to the open front door for a breath of fresh air.

It was a very soft and balmy air which met him, and the world around seemed full of life. Insects buzzed and flashed to and fro, and birds were singing at the utmost pitch of their voices on all sides. The sun had just dipped below the horizon, and long red clouds lay over distant hills, bright with his radiance. Though the country round could not be called pretty, it looked pretty now, as almost any English country does on a fair June evening.

A bush near was clothed in wild clematis, and wild white rosebuds were bursting into bloom upon the hedge beyond. The muddy little stream, flowing amid grass and flags, carried a gleam of red.

Mr. Dale did not seem to enjoy the prettiness. His eyes had an unhappy careworn expression; and he sighed profoundly so soon as he found himself alone.

Perhaps the sigh was loud enough to penetrate into the room behind, where Pattie was busy, putting a few last touches. It was easy to see that Pattie was tired with her week's toil, very tired indeed. The blue eyes were heavy, with dark shadows under them, and the small face was quite colourless. Yet as she came to the door, perhaps in response to that sigh, she smiled and spoke in a cheerful tone; for when Mr. Dale was depressed, Pattie was sure to wear a bright face.

"How the birds do sing, daddy! Isn't it sweet?"

"My dear, a man has to be easy in himself before he can enjoy birds' singing."

"Do you think so? They comfort me. Poor little things—they all seem so happy."

"For how long, I wonder?"

Pattie was silent, and Mr. Dale made a doleful attempt at a rally.

"Come—this won't do. I get a fit of the dumps now and then—not much wonder if I do, considering! But you mustn't mind me, my dear. Things can't be helped. How are you doing in the house? Got everything ship-shape?"

"I have just finished the books. They look nice. Come and see them."

She led him in as if he had been a child, and showed him the small book-case in their tiny dining-room, neatly filled.

"We must read them all through together. I think books are such friends, don't you? The only friends you and I are likely to have."

"But why? Why shouldn't we make new friends in Putworth? There are nice people everywhere."

Mr. Dale shook his head. Then he surveyed the ceiling with doubtful eyes.

"Seems to me this house is not too well built," he remarked. "Just look at those cracks. A house that hasn't been standing six months! I don't understand it. Wonder I didn't see them sooner."

"It is a cracky house altogether," laughed Pattie. "There are cracks in the sitting-room as well, and all up the side of the passage. I never noticed them till to-day; at all events, I didn't see they were so big. And in my bedroom they are just as bad. It can't be helped. They don't look pretty, but we mustn't mind that. When you can spare a shilling or two, I'll get a few Japanese fans to pin over the worst of them, and then they won't matter."

"Let me look at your bedroom, dear. I did not notice anything there."

Pattie felt disinclined to go upstairs. "It doesn't signify," she said. "Lots of houses have cracks in them."

"Not new houses, like this one, only just built. They ought not."

He began to mount the staircase, and Pattie followed slowly. She wanted to see all the best points in their new home, not the worst, and she knew her father's tendency to get into a mournful mood over small discomforts. Naturally these big cracks, which oddly enough had made no previous impression, seemed less important to a young girl than to a man.

Mr. Dale went round her little bedroom, which lay above the dining-room,—his own being over the "sitting-room," so-called, while the maid slept over the kitchen. He examined the various cracks with anxious eyes, felt those that were within reach, murmured to himself, went into the other rooms on the same floor, and presently came back to Pattie, who had seated herself on the window-sill. She was too tired to remain standing. It was a rather low and wide window-sill, and afforded a comfortable seat.

"Pattie, I must have a talk with the landlord. There's something wrong. Cracks in my room, too, and in the girl's—some very bad ones. I shouldn't wonder if Mr. Cragg has been taken in somehow. He wouldn't have taken us in, I'm sure, on purpose. Those cracks weren't there when you and I first looked over the house. I know they were not. I should have seen them directly. Nor when we came last week. I believe they have all begun in the last day or two. We couldn't have overlooked them, you know. It's impossible."

He inserted the tip of his finger into a wide one near the bed.

"Just look at this. Of course we should have noticed it. Quite out of the question that we should not. It must have come in the last day or two. Something must be wrong with the foundations."

Mr. Dale stood surveying the wall with a gloomy air.

"Some people never seem to be allowed to settle down anywhere. I did really think we had found a quiet corner in the world, where we might be in peace. And it seems I was mistaken. No sooner are we here than fresh troubles begin. It really is hard. Such a nice little house, and just the right size; and now I daresay we shall have to turn out and go elsewhere."

"O no, father. A few marks in the walls don't matter. Perhaps our landlord will have them seen to. I'm sure he will do what he can."

"My dear, if the foundations are unsafe, we could not remain. It would not do. Really it is very tiresome—very unfortunate."

"We can't do anything to-night, at all events," and Pattie tried not to yawn. "We must go to bed and get rested, the first thing. To-morrow you might see Mr. Cragg, and ask him what he thinks. But I daresay he will say that the cracks don't matter, and that they have always been there."

"The house has not been built many weeks—months, at all events. And the cracks were not there one week since, I am positive—quite positive."

Pattie turned her head to look out of the open window. The sky was of a clear pale blue, and the red cloud-streaks had turned to a faint yellow. A bird flew past, uttering impatient little cries, and then a moth swept near. Pattie was gazing down the road which led from Putworth, and she saw a figure advancing along it. Something in the outline of the figure seemed familiar, and she studied it earnestly.

"I do believe that is Mr. Cragg himself, coming to see us. Or perhaps he only means to take an evening walk. You could meet him if you like, daddy."

No answer came, and Pattie turned her head, to find that her father had left the room. He called, after a moment, from the passage,—"I'll be back in five minutes. Just going out on the roof to take a look."

There was easy exit, Pattie knew, by means of steps and a good trap-door; but it seemed to her unnecessary trouble. She remained where she was, glad to be able to rest; and silence followed.

The door of her room was wide open, and the trap-door also. Suddenly a shout in her father's voice startled her. Something in the tone seemed to portend disaster, and a cold shock of fear went through the girl. She did not catch any words, it was the tone only which alarmed her; and she would have sprung up to go to him, but there was not time.

She was seated in a somewhat cramped position on the sill, her feet inside, her face turned the other way. Till that instant she had been looking down the road.

Afterwards she never could recall exactly what happened next. She was vaguely conscious of a whirl of noise and confusion, everything about her seeming to give way together, while she herself remained where she was. She had, indeed, no power to stir. A numbness seized her limbs, a kind of paralysis overwhelmed her, as the flooring of the room sank away, together with the whole opposite wall and part of the two side walls. Only the front wall of the house, which held the window in which she sat, and parts of the side walls, stood firm. The greater part of the house was gone, collapsing into some large hollow below.

Of the roof hardly a trace could be seen; and with the roof was gone Mr. Dale, who had been standing on it. Pattie found herself left behind, seated on the sill, with no flooring beneath her feet; a tumult of terror and agony surging in her brain.

CHAPTER III

Mrs. Anthony Cragg

"WHEREVER are you off to now, I wonder?" demanded Mrs. Cragg.

"Business, my dear."

"That's something new. I thought you always said you didn't choose to do business out of business hours."

"Well, then, it's amusement, if you like," said Mr. Cragg.

"I don't see why you need pretend that a thing is what it isn't, either."

Mrs. Cragg tilted her head in a superior fashion. She was vexed that evening, because she had just passed Mrs. Smithers, the chemist's wife, coming out of the chemist's snug house beyond the church. It was a standing grievance with Mrs. Cragg that her husband would obstinately persist in living under the same ample roof with his goods. Other tradesmen of his level in the place had their private houses at a distance, where their wives and children might disport themselves at pleasure, free from touch of shop-keeping. Mrs. Cragg, who loved to describe herself as "a lawyer's daughter," considered that she had taken a downward step in the world by marrying Cragg; and she could not forgive him for refusing her the private house for which she thirsted.

That he actually could not afford such a step was of course absurd— ridiculous! Mrs. Cragg knew better. Though he had as good as told her so, she did not believe it. She had married the man whom she regarded as the richest and most successful tradesman in Putworth, and it would have taken a good deal to shake her belief in his prosperous circumstances. She ascribed his refusal entirely to his overweening devotion to Dot, of whom, though Dot was her own child, she felt actually jealous.

No doubt Cragg would have sorely missed the child's presence under his roof all day. Now he could run for a peep at her if he had but five minutes to spare; and often the little one would creep into that part of the building where he happened to be, drawn by secret strings, and always content if he were near. If she were living away in another part of the town, he would seldom see her, except in the early morning and on half-holidays, unless, indeed, he went home punctually to early dinner. None the less, the avowed reason was true, although it did not stand alone.

"It may be business, and yet not shop-business," Cragg said, in explanation.

"If you'd been brought up as I was, you wouldn't be so desperate fond of talking about 'shops,'" quoth Mrs. Cragg, nose in air. She had a considerable nose, which required much tilting before it would rise to the occasion.

"My dear, you knew pretty well how I was brought up, before you married me," Cragg answered calmly. He could afford to be calm. He was a man known and liked and trusted in the country round; and not a gentleman within ten miles did not enjoy stopping for a chat with "Cragg of the Furniture Warehouse," when opportunity served. Cragg knew this, of course—quietly, and without conceit. His was the right sort of self-respect, which means an absence of all pretence. Cragg was perfectly well aware that his own family name had been untarnished for at least three generations past, while that of his wife's father and grandfather had been of a shady nature—in spite of which he had married her. In the opinion of his friends, he had been the one to take a downward step. But the idea of reproaching her with these facts never so much as occurred to him. He was content with his own certainties.

"Where are you off to?" she inquired.

"Going to see if the Dales are settled in all right."

"If you're not demented about those Dales I don't know who is. You'd better have taken my warning. That man isn't to be depended on. You'll be sorry some day."

"We shall see."

"Well, if you are, you can remember what I said. I don't know what in the world you can see to like in them. It's 'Dales, Dales, Dales,' morning, noon, and night with you."

Mrs. Cragg had only herself to blame if things were so. She could not see her husband cross a road without smartly requesting to be told his destination. This was her way of being wifely and confidential. If he opened a letter in her presence she demanded to hear the contents; and if he unlocked a drawer she wished to be told what he had lost. After forty years of undisturbed bachelorhood Mr. Cragg was reserved in his ways, and seven years of married life had not effected a cure. Perpetual questioning still gave him a succession of shocks.

He would not be easily betrayed into a loss of temper, which also means a lessening of self-respect, but he detested jars and arguments. The natural result of his wife's prying tendencies was in him a growing inclination towards secretiveness in small things. More and more he concealed in his own breast the things that he thought or that he meant to do.

He certainly was aware of an unwonted interest in "those Dales," as his wife called them. He liked the man, though Dale perplexed him, and he liked and was sorry for the girl. She looked so old and so serious for a child of her years. Not that Cragg knew her years; and he would have been surprised to learn that she had passed her sixteenth birthday. He supposed her to be about twelve or thirteen, and he often told himself that he would not like merry little Dot to look in eight or nine years like Pattie Dale.

Despite Mrs. Cragg's opposition, he did not change his intention of going to the house to see if his new tenants were comfortable; but he started in an opposite direction, simply to evade further remarks. It would be easy to work his way round outside Putworth.

The ruse was of small avail. Mrs. Cragg watched him go, and tossed her head.

"As if I didn't know!" she said aloud. "He's crazed about those people. He'll go to-night before he comes home if it takes him two hours to get there. He's as obstinate as an old mule, once he takes a notion into his head. We poor women have a lot to put up with in the men, and no mistake! Anyway, I'm sure I have."

It never occurred to Mrs. Cragg that her husband might also find a great deal to put up with in her.

"I'm sure I can't think why in the world women ever marry. They're a deal happier without. A lot better keep oneself to oneself, and not be bothered."

But she would have been astonished to learn that the very same wonder had more than once occurred unbidden to Cragg,—regarding the man's side of the question. He had known less "bother" as a bachelor than as a husband.

Still, the question was answered differently by Mr. Cragg. Being a man, he thought of other circumstances in connection with the main point. Dot had to be considered. Had he remained a bachelor, there would have been no tiny loving daughter to rejoice his heart.

With this recollection in his mind, Cragg went off, smiling happily to himself. He had just spent an hour in Dot's company before she was put to bed, and he had found her very good company. She was full of fun and full of talk. Nobody called Dot a pretty child, but she was a most loving one to her father, and that was all that really mattered. When he and she were together the two were perfectly happy.

It did not take Cragg two hours, but it did take more than one hour to saunter round by the outskirts of Putworth to the north end of the town, where lay his new possession and its inmates.

Cragg, on the way thither, imagined his own arrival, and pictured a pleasant reception from the tall man and the sad-faced girl, both of whom in different ways had captured his fancy. He thought he would apologise for calling, and would make a feint of going away at once, after just asking if everything was comfortable and to their minds. Then perhaps Mr. Dale would persuade him to stay for a little chat, and he might give in to the proposal. Cragg enjoyed chatting with Mr. Dale, who seemed to be a well-read, intelligent man, with pleasant manners, though disposed to melancholy.

But in all Cragg's picturings of what was to happen, he never approached the reality.

After quitting the town he had to walk a little way along a road, with rough ground on either side. No other houses lay near, except one row of small workmen's cottages down a lane to the right. Cragg passed that lane, and went straight on. He could see the newly built house clearly, and a figure seated in the front window over the dining-room drew his attention. That was at the moment when Pattie noticed him, and remarked upon him to her father.

"It's a nice evening," Cragg murmured aloud. "Shouldn't wonder if Mr. Dale was to think the place pretty to-day."

The croak of a frog on the border of a muddy stream beside the road made him turn his eyes in that direction. He stopped, and poked absently among the herbage. While doing this, he became aware of a prolonged rumble.

"Thunder! Dear me, I shouldn't have thought it!" uttered Cragg.

He looked at the clear sky, dotted with tiny cloud-fleckings, and wondered—could it be thunder?

Cragg turned towards the house, and stood petrified. Part of the building was still there, dimly visible through a cloud of dust; but something very strange had happened.

He might be a slow man generally. At this moment he was anything rather than slow. The first shock over, he literally bounded forward. A greyhound or a deer could hardly have improved upon the speed with which he covered the space between him and the ruin.

For a ruin it was. As he drew near, gasping audibly for breath, he saw that only the front wall and portions of the two side walls remained intact. The remaining portion of the house had disappeared. When the dense cloud of dust slowly lessened, he detected a slight figure in the window above, clinging there in a convulsed and terror-stricken stillness. Beyond was chaos—a dark gulf, into which the building had disappeared.

No voice spoke, no human being stirred. Cragg could see nothing of Mr. Dale, or of the maid-servant. Only Pattie Dale was visible, and Cragg hurried beneath the window.

"What does it all mean? Are you hurt?" he cried. He was close enough to render shouting unnecessary.

Pattie made no reply. She seemed to be dazed, perhaps hardly conscious. He could see that her blue eyes were widely-opened in a fixed stare.

"My dear," he called, "you must wake up; you must let me help you down. It isn't safe there." A shudder passed over him, as he realised that at any moment this wall, too, might descend into the gulf, carrying her with it. "Rouse up, my dear. Try to hear what I'm saying. I'm Cragg, you know, and I want to get you down. You must drop into my arms. See?"

She seemed to him a mere child, and he was thinking of Dot—feeling unspeakably thankful that Dot was not in Pattie's place. The thought of Dot made him the more eager to rescue Pattie. "Come, my dear,— come!" he called.

At first Pattie paid no heed, but gradually her eyes turned in his direction, and a look of consciousness crept into them.

"What is it? I don't understand," she said at length. "Why am I here?"

"You're not going to stay there. Things have gone wrong, and we've got to put them right," called Cragg cheerfully, relieved to have her attention. "See!—I'm close by. I want you just to edge your feet over this side, and to let yourself drop. Don't be frightened—move slowly. No hurry. Just slowly—gently—"

He was in deadly fear lest she should fall on the other side of the wall, or lest the slight additional shake of movement on her part should seal the fate of the wall itself, and it too should go down, carrying her to death. She did not move at once, but after a little pause said vaguely:

"What am I to do? I don't understand."

"My dear, look this way,—this way—this!" urged Cragg, with intense earnestness, standing below the window and holding up his arms. "Don't think about anything else. Look at me, and think of me. Keep your head this way, and just bring your feet over the sill—quietly. Don't hurry. Don't look anywhere else. It's all right. I'll catch you. I won't let you fall. So—yes—that's grand-both feet over. You'll do it directly— and then—"

There was no need for any further exhortations. Pattie's strength proved equal to the moment's need so far; but the instant both feet were over, it failed her. She fell sideways, helplessly; and Cragg caught her, as he had promised. Though the height was not great, the ceilings being low, her weight brought him to the ground. He was undermost, however, and started up again, regardless of bruises.

"Not hurt, are you?" he asked anxiously.

Pattie seemed to be awakened by the shock of her fall. She sat up, looking with troubled eyes.

"No, I'm not hurt," she said slowly. "What does it mean? What has happened? Where is father?"

To this serious question Cragg dared not attempt at once to find an answer.

"Come a little way farther off," he said.

"That wall might go down too. Come this way. You're feeling queasy, aren't you?"

"Yes. I don't know where I am. I don't know what it means."

Pattie spoke slowly, like one bewildered. Then her eyes went to the ruined house, and recollection flashed up. Till then she had been stunned. A cry broke from her.

"Father! father! He was on the roof. Where is he?"

But for Cragg's detaining grasp she would have rushed to the edge of the depth. He caught her, and held her back by main force. She struggled fiercely, then fell back, senseless.

"Thank God for that!" muttered Cragg, tears in his eyes.

CHAPTER IV

A Rescue

IT is only fair to Anthony Cragg to say that in this first hour his thoughts were not of himself, nor of the heavy loss he would suffer. That part of the matter had to await later attention.

Without delay he carried Pattie farther off, and laid her down, senseless still, upon the grass. Then he walked quickly to the side of the ruin, studying with troubled eyes the open gulf into which his new structure had descended.

He could conjecture what had happened. This had been in the past, to some extent—never a large extent—a mining neighbourhood; and two or three disused mines not far off were known to the people of Putworth. Here probably was another old mine, long forgotten; and the weight of the house had broken through the thin roofing. Otherwise it might have stood the danger undiscovered. The greater part of the building had descended, and the rest might at any moment follow. That depended on whether the front wall of the house rested on a firmer basis than the other walls, or whether it too lay over a hollow, with only a thin roof to hold it up.

As to what had become of Mr. Dale and the maid-servant, Cragg could feel in his own mind little doubt. He believed both to have gone down with the ill-fated house; and if so, both must surely have met their death.

Yet, as he said this to himself, his ears were saluted by a terrified—"Oh, sir!"

"What! You're safe?" cried Cragg.

"Yes, sir; I was out in the back garden, getting a bit of green,— parsley, I mean," panted the girl, who seemed tolerably self-possessed, except that her eyes had in them a frightened stare. "And when I see everything go to bits like that, I just dursn't do nothing."

"And left Miss Dale to take her chance! If I had not come, what do you suppose would have become of her?"

Cragg spoke sternly, and the girl began to sob.

"Well, never mind now. You were startled, of course. Come and see to her. Here! this way. And mind, on no account let her go near the house." Cragg paused, doubting if any one but himself would be equal to the task of holding back Pattie, when she should again revive. "No; on second thoughts, I'll stay here. Go to those cottages, and call the men—any who are there. Tell them what has happened. Say ropes will be wanted. Quick! don't lose a moment. I'll see to Miss Dale."

The girl fled, crying as she went, and Cragg went back to Pattie. He was relieved to find her coming to, though still hardly conscious.

"Not much hope for him," he murmured. "Don't know what the depth of the fall may have been, but he couldn't escape. She's an orphan, I'm afraid."

Leaving her again, he approached the edge cautiously, not too near, and raised his voice in a shout. No sound replied. Cragg tried again, and then he felt a touch on his arm. Pattie was standing by his side, her eyes shining, her face colourless.

"Is he down there?" she breathed. "Can't you get him up? He may be hurt."

Cragg fell in with the suggestion.

"Yes, yes, my dear, as soon as possible," he said cheerfully. "I've sent the girl to call some men, and we'll do our very best, you may be sure of that. They will be here directly."

Pattie looked at him with steady eyes.

"You think he is not killed?"

"I shouldn't wonder if he's stunned; yes, he must be stunned. He hasn't answered me, but that doesn't say much. You see, it may be a good way to go down. I'd no notion there was an old mine hereabouts, but that's what it's bound to be. An old mine near the surface, you know, so the roof wasn't strong enough to bear up a house on it for any length of time. Must have been giving way slowly for weeks past, I shouldn't wonder. If I had guessed such a thing, I'd never have built the house. Nobody had any notion."

"Is father in the mine?—far down?"

"Well, you see, I don't know," explained Cragg. "It might be the old pit mouth just hereabouts, or it might be only into one of the pit-galleries. There's no telling—nor how shallow it may be either. We'll soon find out."

"Father and I saw a lot of cracks in the walls to-day."

"Most of the houses here get cracks; it's from the nature of the soil. I did see some last week, and I thought they were showing uncommon early. That was all. I'd no notion of anything of this sort," repeated Cragg regretfully.

Pattie sighed.

"Father must think it so long. He must want to get out. I don't know how to wait. Couldn't we do something? If I were to go close, and call out,—he might know my voice."

"No harm trying," assented Cragg. "Not close, but a little nearer; it isn't safe close. The earth might fall in any moment. If he's stunned, he won't hear your voice no more than mine; but we'll try." He was desirous to keep Pattie's mind occupied until the men should arrive. "This way; not any nearer. Now, call."

Pattie obeyed, raising her thin tones once, twice, thrice, with a manifest effort.

"Father!" she cried first; and then, "Daddy! Daddy! Don't you hear me? Oh!"

She broke away from Cragg, taking him by surprise, and ran several paces before he could catch her.

"I heard father's voice. Let me go! Don't keep me!" she implored. "He cried out. Listen!"

A faint sound could be detected, seeming to come from underground.

"Pat—tie! Pat—tie!" it said.

"Father, we're here. We'll get you out. Don't be afraid," called the girl; and then wildly to Cragg, "Let me go! What can we do? Let me go!"

"Will you promise to do as I tell you, and not to stir unless I give you leave? I'll hold you till you do promise."

"But I want—O how can I?" gasped Pattie.

"What good will it do him if you kill yourself? Be sensible. Think what your father would wish you to do."

Pattie became suddenly quiet.

"Yes, I will," she said. "I'll be good. I'll stay here till you say I may move. Do ask him if he is hurt."

"I know you'll keep your word." Cragg left her, and went nearer, calling in strong tones, "Pattie is safe. Are you hurt?"

"Yes," came faintly, after a pause. "Keep—her—back."

"Where are you? Is it a mine?"

"I don't—know. I'm lying on—something—all dark—"

"We'll have you out in a jiffy!" shouted Cragg.

He saw the men hurrying across a space of rough ground, which lay between this part and their cottages. Afterwards it came out that they had heard the noise of the falling house, and had, like Cragg, mistaken it for thunder. Since the wind blew from them to the house, the noise was lessened.