The Doings of Doris

Agnes Giberne

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

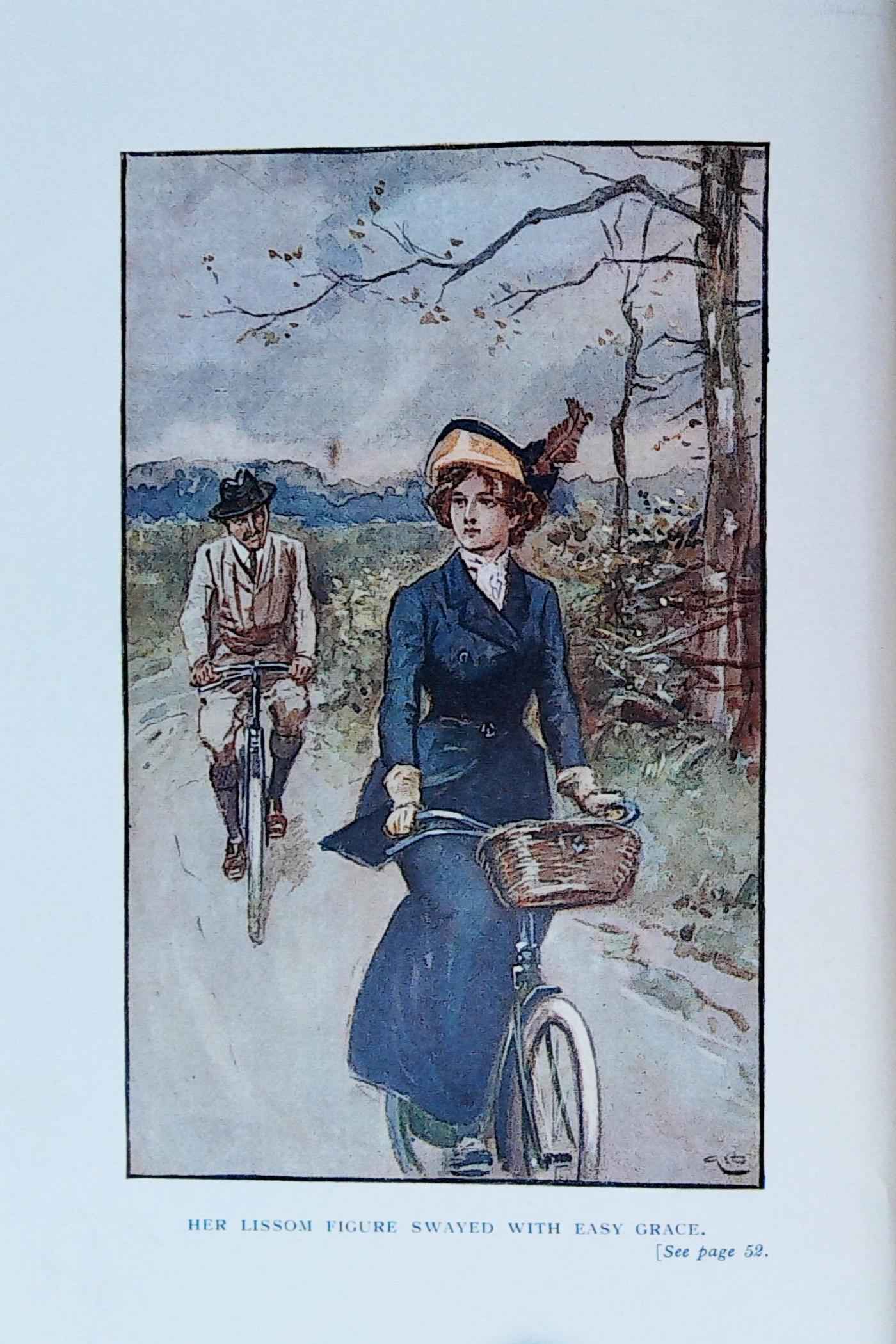

HER LISSOM FIGURE SWAYED WITH EASY GRACE.

THE DOINGS OF DORIS

BY

AGNES GIBERNE

Author of "Sun, Moon and Stars," "Life's Little Stage,"

"Stories of the Abbey Precincts," "This Wonder-World,"

etc., etc.

"A MAID IN HER EARLY BLOOM."

— J. Whyte-Melville.

LONDON

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

4 Bouverie Street and 65 St. Paul's Churchyard E.C.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

I. THE OWNER OF CLOVER COTTAGE

II. BAITING THE GROUND

III. DORIS REBELS

IV. THE MORRIS'S

V. A SECRET AGREEMENT

VI. DORIS LETS HERSELF GO

VII. THE CYCLE RIDE

VIII. MRS. BRUTT SUGGESTS

IX. SUDDEN SILENCE

X. A SURPRISE VISIT

XI. THE PORTRAIT

XII. A LITTLE PLOT

XIII. HAVE I DONE WRONG?

XIV. THE STRANGER

XV. R. R. MAURICE

XVI. THE CRY FROM THE CHÂLET

XVII. A GREAT EFFORT

XVIII. ON THE MOUNTAIN

XIX. A ROTTEN PIECE OF ROCK

XX. ONLY A GIRL!

XXI. A SUPERB RESCUE

XXII. TWO HEARTS DRAWING NEARER

XXIII. ALMOST OVER

XXIV. "BUT I'M AFRAID"

XXV. THE SQUIRE'S ADVICE

XXVI. NOT HER HUSBAND

XXVII. THE EAVESDROPPER

XXVIII. WHAT MRS. BRUTT HEARD

XXIX. WHAT NEXT?

XXX. THE SQUIRE IS MYSTERIOUS

XXXI. THE SQUIRE'S DARK HOUR

XXXII. "YOU DON'T KNOW DICK"

XXXIII. "HOW WILL HE TAKE IT?"

XXXIV. FOILED!

XXXV. WOULD HAMILTON DO?

XXXVI. A SURPRISE MEETING

XXXVII. THE MISCHIEF-MAKER AGAIN

XXXVIII. "WHO WAS MY FATHER?"

XXXIX. "THAT WAS WELL DONE!"

THE DOINGS OF DORIS

CHAPTER I

The Owner of Clover Cottage

"A DELIGHTFUL man!" Mrs. Brutt declared. "Absolutely charming! Handsome—accomplished—clever—fascinating!" She hung impressively upon each adjective in turn. "Fortune has showered her gifts upon him. Has simply showered them."

Mrs. Brutt viewed her present companion as the reverse of charming. But to one who hated solitude, anybody was better than nobody; and she had seized a chance to inveigle him indoors, much against his will.

"Showered—gifts—" he repeated vaguely, his one thought being how to escape from durance vile.

"Ah, your masculine mind is occupied with weightier matters!" —and she rippled into laughter. She had a habit, not agreeable to all hearers, of interlarding her speech with ripples.

"I was speaking of the Squire. As I say—a most attractive character. So good of him to come and take tea with me in my humble cot! Overwhelmed as he must be with engagements! I assure you, I appreciate the compliment."

Mr. Winton's grunt might or might not have spelt acquiescence.

"And his niece—such an attractive woman! So distinguée! That word does just exactly describe her. Not that I have seen so much of her as of her uncle." She had met Mr. Stirling three times, and Miss Stirling once. "But enough to realise what a perfectly unusual character hers is."

The Rector grunted anew. He never discussed one parishioner with another; and he hated gossip with a deadly hatred.

"So touching to see his devotion to her—really quite beautiful! I am told that she has been everything to him since his poor wife's death— ten years ago, wasn't it? A great sufferer she must have been—and such a sweet woman. Everybody says so. And now he just leans on his dear niece. So touching, isn't it?"

No reply. Grim silence.

"Then, too, there is Mr. Hamilton Stirling—a most interesting man. So full of information. Really, it is a privilege to come across a mind like his. Do tell me—is it true that he is the heir to all this property—supposing, of course, that the Squire never marries again?" She rippled anew. "First-cousin once removed, isn't he?"

"Yes," was the least that the Rector could say.

Mrs. Brutt understood that she would get nothing out of him, and she resented the fact. Her eyes surveyed with veiled criticism his ungainly figure, broad and heavy in make, thrown as a blur against a background of dainty colouring. He wore a rough workaday apron, suggestive of carpentering, over an ancient coat; both being, under supposition, never seen outside his shed. But when pressed for time, he would steal across for a word with his friend the carpenter; and more than once Mrs. Brutt had captured him en route in this unclerical guise. He had begun ruefully to see his own lost liberty, now that a talkative lady, with leisure for everybody's concerns, had chosen to plant herself within a stone's throw of the Rectory back-garden gate.

Hitherto the back lane had been little frequented, and he could do as he chose, with small fear of detection. Though Lynnbrooke had become a town, its growth had been mainly towards other points of the compass, leaving the old parish church and the original village almost untouched.

But Mrs. Brutt, coming for a week's change to the Inn, took a fancy to a couple of low-rented cottages, standing empty, and decided to make them her home. She had them transformed into a cosy dwelling, sent for her furniture, and settled down therein, with much flourish of trumpets.

For a while she was too busy to give heed to aught beyond the process of settling in. That ended, she found herself with superabundant time at her disposal, and during the last two months her presence had been in the Rector's eyes a standing grievance. He never could pass down the lane without a risk of being waylaid. Whatever else Mrs. Brutt might be doing, she seemed to have one eye permanently glued to her front window.

Capture on Monday afternoon was an aggravated offence. He counted Monday his own, free for the dear delights of his carpentering shed. So, though he came in because she insisted, he chafed under the necessity. Where she put him he remained, watching for the first chance to get away. Deep-set eyes under shaggy eyebrows rebelled; and the solid cogitative nose, broad at the tip with a dent in the middle, twitched impatiently. When she made a pause, he heaved himself to his feet, capsizing a fragile table.

"Sorry! I hope nothing is damaged." He picked it up gingerly. "I can't stay longer, I'm afraid. Sermon to write."

"Ah, were you going home to write your next Sunday's sermon?" The dulcet tones held a sting of unbelief, and naturally, since his face had been turned the other way. "You don't leave your choice of a subject till the last moment. So wise of you!"

A twinkle in the deep-set eyes showed appreciation of this. She stood up slowly.

"And your daughter, Mr. Winton,—the sweet Doris. Do tell me about her. We have not met for days. I am so interested in that dear girl. She is so unusual—so charming—so clever and bewitching!"

It was hardly in father-nature not to respond to this,—even though he did not believe that she meant what she said. He and she had been antagonistic from the moment of their first meeting. None the less, he paused in his retreat, that he might hear more.

"I assure you, she has quite taken hold of me. Quite fascinated me. Such a charming face—hers! I adore hazel eyes, and hers are true hazel—positive orbs of light." The Rector uttered a silent "Bosh!" to this. "Now that I am unpacked and arranged, I hope to see a great deal of that dear child. Tell her so, please, with my love. We are such near neighbours—" "Much too near!" silently commented the Rector— "that I hope she will be always in and out. Tell Doris—may I call her so?—that it will be a real charity, if she will come as often as possible to my little cot."

Why couldn't she say "cottage" like a sensible being? Mr. Winton hated being humbugged, and he abhorred gush. Praise of his Doris was sweet; but he could not quite swallow all this.

Mrs. Brutt studied through draped curtains his swinging stride down the little pathway.

"Of all uncouth beings! The contrast!" murmured she, setting alongside a mental picture of the Squire.

"And his wife. Not so uncouth, certainly, but really more unendurable. The girl's life, under such a regime, must be no joke. I wonder how she stands it, for my part."

Mrs. Brutt strolled round the room, which was crowded with furniture, with pictures, and with bric-a-brac ornaments, many of them old and valuable. She altered the position of one or two, thinking still about Doris Winton.

"A pretty girl," she murmured,—"and with pretty ways. She might make a sensation, away from this poky place. I wonder whether, some day, I could bring her forward. Not an impossible plan. What if I were to offer to take her abroad? I doubt if the Rector would approve. He likes me as little as I like him. But if I can get hold of the girl somehow—" She clapped her hands and laughed aloud. "I have it! I'll suggest the idea to the Squire. That will do. He simply rules the neighbourhood."

A ring at the front door took her by surprise. She glided to the window, just in time for a glimpse. Actually!—it was the Squire himself. Again—already! The impression she had made on him must have been agreeable. This flashed through her mind as she fled to the mantelpiece and anxiously surveyed herself. Although past forty, she knew that no grey lines had begun to appear in her well-dressed dark hair; and while she was a plain woman, so far as features were concerned, she also knew that her figure was good, and that she could carry herself with the air of being a somebody.

"Mr. Stirling" was announced. He found the lady engrossed in a book, which she put aside with a dreamy air, before beaming into a surprised welcome.

"This is a pleasure indeed. A most unexpected pleasure. How kind—how very kind! Pray sit down."

The Squire had called in passing, to leave a small volume on architecture which she had said she wished to read. He came in only to point out a passage bearing on the structure of the parish church; and he had not meant to stay. But protests proved useless. He, like the Rector, found that once inside Clover Cottage, it was not easy to get away.

CHAPTER II

Baiting the Ground

"You remembered what I said. How thoughtful!" Mrs. Brutt turned over one or two leaves of the book. "It looks absolutely fascinating. I adore reading. After the society of friends—" and she sighed—"it is the chief solace of my lonely hours."

"I hope you will not be lonely here." The speaker was in age over fifty, and in looks singularly young, with few grey hairs and a spare alert figure. His features were good, and his expression in repose rather severe; but the smile brought irradiation. People thought much of him, both for his unfailing kindness and courtesy, and for the fact that his forbears had owned the land round about since the days of the early Henrys. He was perhaps the most popular man among rich and poor in the county.

Mrs. Brutt presently alluded with a smile to her last caller. "Such a dear good man and so deliciously unconventional. Don't you delight in that sort of moral sublimity? And dear Mrs. Winton—the busiest of rectorinns! That word just describes her. So useful! So efficient! She seems to understand everybody, and to think of everything. Quite delightful, is it not! Positively, I envy her. Such a soul for doing good."

The Squire hated gossip at least as much as the Rector; but he was not so quick to detect its presence. Still, an uneasy bend appeared in his smooth forehead, which acted as a danger-signal to the astute Mrs. Brutt, before he was himself aware of uneasiness. She dropped the dear good Rector and his wife like a pair of hot potatoes, and skated in a new direction.

What charming country it was! Such lovely scenery! Such numbers, too, of sweet farms within reach. Didn't Mr. Stirling look upon English farm-life as a perfectly ideal existence?

"I had a drive yesterday afternoon, to return the call of your sister-in-law at Deene,—I beg your pardon, your cousin I ought to have said. Such a charming woman! I'm really quite in love with her already. And her son—one of the best-informed men I ever came across. One longs to sit at his feet and learn."

The Squire failed to echo this aspiration. Mrs. Brutt, noting his look, resolved to be in future more sparing in her praise of Mr. Hamilton Stirling.

"Then the driver took me a long round by the loveliest spot imaginable—'Wyldd's Farm'—such an appropriate name. One of your farm's, he told me; as of course I might have guessed. I walked through a large field to get a nearer view; and the farmer himself came out for a chat. Not the new-fangled sort, but the real old-fashioned type—quite idyllic!—a genuine old yeoman. He simply charmed me. So respectful. So self-respecting. I hoped he would ask me to go in, for I saw the sweetest little face of a girl looking out of the window, and I wanted to know her. He didn't—but I shall go again, and perhaps next time he will."

Surely she had not "put her foot in it" this time! The Squire's forehead was puckered all over, fine lines ruffling its surface. She racked her brain to discover wherein the blunder had consisted, while glissading off into fresh paths. Her exertions met with success, and gradually his look of annoyance faded.

"The real delight of country is, after all, in long walks," she remarked. "I can't afford many drives. But walks—with a companion— are delightful. Real long rambles, I mean."

"Miss Winton is a good walker," he said, as he stood up.

Mrs. Brutt caught at the suggestion. She did so admire Doris Winton; a captivating creature, pretty, graceful, full of life, "the dearest of girls." And wasn't it touching to see one, so fitted to adorn society, devoting herself to parish drudgery? So good and useful! But rather melancholy—didn't the Squire think?

"Of course one knows that the work has to be done. And the Rector's daughter has to take her share. But there are limits. And she is so young—so taking! For my part, I do like young folks to have a merry time—not to wear themselves out before they've had their swing."

Mr. Stirling's attention was arrested.

"Does Miss Winton work too hard?"

"Pray don't count me meddlesome." Mrs. Brutt put on a deprecating smile. "As a stranger, I have no right to speak. But sometimes—don't you think—sometimes strangers see more than friends? I can't help being abominably clear-sighted. It isn't my fault. I suppose I'm made so. And—I'm speaking now in strict confidence—" she lowered her voice to a mysterious murmur,—"I do feel sorry for the girl."

"For Doris Winton!" His manner showed surprise.

"Oh, you men!—you see nothing. You never do. She is bright enough in a general way. She doesn't give in. A brave spirit, you know— that's what it is. She makes the best of things, and people don't notice. Not that she meant to betray anything to me,—poor little dear. Oh, she is thoroughly loyal,—never dreams of complaining. But one cannot help seeing; that's all. I always do see—somehow. And I confess, I positively ache to get that dear child right away out of the treadmill, if only for a few weeks. To take her abroad, I mean, and to give her a really good time. It would mean everything to her— to health and character and—everything. However, at present I don't see my way. What with building and settling in, I have run to the utmost extent of my tether. Poor dear little Doris. It must wait. But it would mean fresh life to her."

Mr. Stirling said good-bye, and departed thoughtfully. Mrs. Brutt felt that she had scored a point. He would not forget.

She went back to her peregrinations about the room, indulging in dreams. Switzerland offered itself in tempting colours. She did not care to go without a companion. But a young bright girl, such as Doris—pleasant, and also submissive—would be the very thing. More especially if she could bring it about that somebody else should undertake all Doris's expenses; and perhaps not Doris's only!

CHAPTER III

Doris Rebels

MR. STIRLING had many miles to ride before turning homeward, but he showed no signs of haste, walking slowly from Clover Cottage. His face fell into a somewhat severe set, till a slight bend in the lane brought him almost within touch of Mrs. Brutt's "dearest of girls," the Rector's daughter.

She stood just within the back gate of the Rectory garden, the centre of a flock of pigeons. One white-plumed beauty was perched on her shoulder; another sat on her wrist. She was of good height, slender and supple in make, with long lissom arms and fingers. Small dainty ears, a pear-shaped outline of cheek, pencilled dark brows over deep-set eyes, and a pretty warmth of colouring, made an attractive picture. A broad low brow, with eyes well apart, spoke of intellect.

"Pets as usual!"

The swish of fluttering wings responded. Doris turned with a smile of welcome.

"I'm afraid I have frightened them off."

"It doesn't matter. The dear things are so shy. Won't you come indoors?"

"Not to-day, I think. Your neighbour down the lane has kept me longer than I intended."

"Is your horse in the yard? Shall we go through the garden?" It was a common practice of the Squire to leave his horse in the Rectory stables, when he had business in the village. She walked by his side with lithe free grace, carrying her head like a young princess. "So you've been to the Cottage. Isn't she nice? I like her awfully." Doris's cheeks dimpled. "But father doesn't. He can't forgive her for being there. If he ventures out in his beloved old coat, she is sure to catch him."

Mr. Stirling stooped to pick up a snail, which he flung far over the wall. Then he admitted that he found Mrs. Brutt pleasant—something of an acquisition.

"When are you coming to see Katherine?"

"I did think of this afternoon—but I'm not sure."

He recollected what Mrs. Brutt had said. "Too much to do?"

Her face took a rebellious set.

"I don't like being made to do things."

"Even if you don't mind the things themselves?"

She laughed, but the rebellious note was still audible.

"I'd rather be free to choose for myself. I hate to have my whole life parcelled out for me by—other people!"

This was a new sound in his ears. Subterranean gases of discontent had been at work; but till this moment the imprisoned forces had found no vent in his hearing.

"Spirit of the Age!" he murmured to himself. Aloud he made a slight encouraging sound, and her words came in a rush.

"I don't see why I should have to do it all. I can't help being a Rector's daughter. If I were a clergyman, or a clergyman's wife, it would be by my own choice. Not because I couldn't help myself. Doesn't it seem rather unfair that I should have to spend my time doing things that I detest, and having none for what I love?—well, not very much, at all events. Oh, I didn't mind so much at first. One likes variety, and it was a change from school. But—lately—"

"Yes—lately—?"

"It has begun to seem—horrid. I've felt horrid sometimes. Don't you know—?" appealingly.

"Perhaps I do. What sort of things is it that you want to do?"

"Oh just heaps! I love music, and I could spend hours over it every day. And hours more over Italian and German. I'm rather good at languages. And I want to read—any amount. And then I should like—" and she paused—"more go—for fun!"

"You are asked to a good many tennis-parties, I believe."

"Heaps of them. But that is the same thing, over and over. The same houses, and the same friends. I should like things to be different. I want to go about, and to see fresh people." Her face flashed into brightness. "If only I could go abroad! That would be too delicious. Not keep on always and for ever in the same old ruts."

She sent a quick glance into her companion's face, and was sure that he understood, though he made no remark.

"I don't mean to grumble. But I do so detest handling dirty old library books, and running the Shoe-Club, and going in and out of stuffy cottages, and hearing all about the old women's complaints. I suppose, if I were really good, I should dote on that sort of life. But I'm not!—and I don't! I do love things to be nice and clean and dainty. And—perhaps it is conceited of me—I sometimes think I could really do something with my music, if only—but there is never any time. Mother likes me to practise every day; but as soon as I begin to get into it, and forget the whole world, I'm morally certain to be called off, and sent to take some wretched note somewhere."

"That must be a little trying."

"It's just horribly trying, and it makes me so cross. Ought I to say all this? Of course mother doesn't mean—but you see, she's not musical. And when interruptions come again and again, I get out of heart, and it doesn't seem worth while to go on. Sometimes I feel as if I must chuck it all, and get right away!—as if I couldn't go on!"

Her face flushed. He questioned—had the elder lady acted as suggester to the girl, or the girl to the elder lady? Some collusion of ideas evidently existed.

"But you like to be useful."

The corners of her mouth curled upward in a protesting smile.

"Ye—es—I suppose so. Not always. And I'd rather be useful in my own fashion. Not in other people's fashion."

No more could be said, for on their way to the stable they skirted the glass door which opened from the Rector's study upon a side-lawn. There stood the Rector himself, in an attitude of bored endurance. There also was the rectorinn,—so named, and not inappropriately, by Mrs. Brutt,—large and comfortable in figure, calm and positive in manner. Though she never spoke loudly, her voice had a penetrative quality.

"Really, Sylvester, with that woman always about you must be more careful. Only last week you promised me never to be seen in this coat. I shall have to give it away."

"Drastic measure!" muttered the Rector.

"I don't see what else can be done. You never remember to change it; and positively I cannot have you going about in rags. She will gossip about you all over the place. If the husband goes shabby, it is always the wife who is blamed."

"Well, well, my dear, I'll be careful."

"You won't. You never are. When once you get to your tools, everything else goes out of your head—promises included. Nothing will cure you but getting rid of the coat altogether."

"The consent of the owner is generally supposed—"

"Not in the case of husband and wife, I hope."

The Rector wondered what his wife would say, if he proceeded to dispose, without her consent, of her best black silk. But he was not a lover of what the Scots call "argle-bargle."

"Hallo!—here's Stirling!"

The Squire made believe to have heard nothing; and the grateful Rector carried him off. Doris was not allowed to follow. Mrs. Winton beckoned her indoors.

"It is a disgrace to us all to have your father seen in such a coat. Absolutely in tatters. Past all mending."

"Everybody knows father, and nobody minds what he does."

"That is precisely why his own people have to mind. Otherwise, there is no check upon him. Doris, those library books are not covered yet."

"I didn't feel inclined yesterday."

"The things that one doesn't feel inclined to do are generally just those that ought to come first."

She spoke positively; not unkindly; but voice and manner jarred, and the girl moved in a restive fashion.

"I want to cycle over to see Katherine."

"You will hardly have time to-day."

Mrs. Winton held out her hand, as the maid brought a note on a tray. Susan hesitated, with a glance towards Doris, but the gesture had to be obeyed. Doris in her turn held out a hand.

"Mother—that is for me."

"Yes. I see that it is from Hamilton Stirling."

Doris flushed with vexation, and retreated to the bow-window. There she stood and read in leisurely style four pages of neat small handwriting. Getting to the end, she smiled, put the sheet into her pocket, and stood gazing out on the lawn. They were still in the study. Mrs. Winton waited two or three minutes, then said—

"I think you should allow me to see your letter, my dear. You cannot have secrets of that sort from me."

Doris faced round, her combative instincts awake.

"What sort?"

"I'm sure you understand what I mean."

Doris seemed embarrassed, though a smile lingered round her lips, and her eyes had a sparkle in them.

"It's—not meant to be shown."

"If you will tell me what it is about, I can judge."

The girl stood, slender and upright, against a dark maroon curtain.

"He says I am not to tell anyone."

"Mr. Hamilton Stirling would certainly make an exception in my case. He would not wish you to hide anything from me."

"He says—nobody!"

"Then I think he is wrong. And I do not think you are bound to follow such an injunction."

Doris's head went up.

"He advises me to read some books on geology."

"That cannot be what he does not wish you to repeat."

"No."

"And at your age—"

"I'm nineteen."

"Doris, you force me to ask you a plain question. Has he made you an offer of marriage?"

"Mother!" The girl crimsoned, and threw out her hands with a movement as of indignant repudiation. "Of course not! Why should he? It is absurd to ask such a thing. But you always spoil everything for me— always!"

Mrs. Winton was vaguely conscious, as the Squire had been, of some new element. She failed to analyse it, and the line she took was unfortunate. A word of loving sympathy would have brought submission; but she straightened her shoulders, and remarked coldly—

"That is not the way in which you ought to speak to me. Are you going to show me the letter?"

Doris caught her breath, said—"I can't!"—and fled.

CHAPTER IV

The Morris's

LYNNTHORPE, Mr. Stirling's home, a large house in a park, lay about two miles from the parish church end of Lynnbrooke. But Mr. Stirling, instead of riding thitherward, shaped his course in the opposite direction, straight through the town. On quitting the latter, he followed a broad Roman road for some two miles, passing then the village of Deene, where lived his cousin's widow, Mrs. John Stirling, with her only son, Hamilton—commonly regarded as probable heir to the Stirling property, since it was believed to be entailed in the male line.

Instead of pursuing the high road, he turned off into a lane, three miles of which brought him to another, very narrow and winding, whence at length he emerged within sight of a lonely farm, upon a bleak hillside.

It was a neighbourhood far from town traffic, far from even the gentle stir of village life. The lane here ceased to exist; and his trot slackened to a walk, as he rode through a large meadow, on a grass-path. Fields of young corn grew near; and the "bent" of some stunted trees showed the force of prevailing westerly winds.

Distant lines of hills were pretty; and there was a healthful breeziness about the situation; but Mrs. Brutt's description of it as "the loveliest spot imaginable" was overdrawn, as her descriptions were wont to be.

Apart from the group of farm buildings stood the dwelling-house, with lattice windows and creeper-grown porch. The grunting of pigs alternated with cawings from a rookery not far off. Mr. Stirling, a fine-looking man on horseback, noted neither, his mind being otherwise engaged.

Somebody came striding through the gate; older by many years than the Squire; bigger and broader; roughly clad, with gaiters and heavy boots. His face, red-brown like a Ribstone pippin, was lighted by the bluest of eyes; his hands, large and muscular, were unused to gloves; his bearing, though blunt and unpolished, was respectful. Yeoman farmer, every inch of him, as Mrs. Brutt had said. For once she had spoken correctly. He smiled at sight of the Squire.

"Fine weather, sir. Good for the crops."

"How are you, Mr. Paine?"

"I'm right enough, sir. I've nought to complain of. And having my niece and her girls here, it do make a lot of difference to me."

"No doubt!"—with a touch of curtness.

"Yes, sir,—a lot of difference it do make. The place was that lonesome with her gone." He had lost his wife some months earlier, and he pushed his cap back with a reverent gesture. "I just put it so to Molly when I wrote; and she wouldn't say 'No,'—bless her!—though it did mean giving up of her Norfolk home. I'd hardly have known Molly, that I wouldn't—she's that changed from the pretty girl she used to be."

"People generally do alter as they grow older." The Squire spoke in a constrained tone.

"Ay, sir,—'tis true. But she's more changed than I'd have thought possible. Twenty-seven years it is now since she went to furrin parts with little Miss Katherine and her father,—and she was a right-down pretty creature, and no mistake, was our Molly. And if so be, as folks said, that she saved little Miss Katherine's life, sir, I'm glad it was so. All the same, it did go agin the grain with me—uncommon agin the grain it went!—Molly getting herself trained for a nurse, when this might have been her home all along. And then going off as she did, all of a suddent, to Canada, without ever seeing of us agen. I misdoubt but Phil Morris wasn't the best of husbands. She's seen a lot of trouble, she has—judgin' from her look."

The Squire was silent and motionless.

"But it seems like as if she couldn't abear now to speak to me of the past,—no, not yet of her husband, Phil Morris. Nor she won't hear him blamed. 'Let bygones be bygones,' says she. Only she's told how good you've been, sir, all these years, letting her have that house in Norfolk, dirt-cheap. I'm sure, if ever I'd guessed—but there!—how was I to know, when she'd never so much as wrote word to me that she was a widow, nor was back in Old England? Nor you never spoke of her to me neither, sir!" There was a note of inquiry, a suggestion of reproach, in the last words.

Mr. Stirling dismounted.

"It was hardly my place to inform you, if she did not wish to do so herself," he said gravely. "I was not likely to forget her care of my niece; and she has been welcome to any help I could give. Would you call someone to hold my horse? Thanks,"—as the farmer took the reins,—"I'll find my way in."

He walked up the narrow flagged path, bordered by such homely flowers as double daisies, pinks, and sweet-williams. Before he could ring the door opened, and a girl stood there—fair-skinned and grey-eyed, with short brown hair curling closely over her head. She had a fragile look; and the small hands were almost transparent. A shy upward glance welcomed him.

"How do you do, Winnie? Better than you used to be? You don't seem quite at your best."

"I'm much the same, thank you, sir."

"Rheumatism bad still?"

He gazed down on her with kind concern.

"Yes, sir. It's no good me minding. Mother's in."

She led him to a long narrow sitting-room, crowded with old-fashioned heavy furniture. Oak-beams crossed at intervals the low-pitched ceiling; and an aged spinnet stood in one corner.

The woman who rose to meet him must have been at least fifty, perhaps more. She was stout, unsmiling, blunt in manner, with features which might in girlhood have been well-shaped. But the complexion was muddy; the face was hard and deeply lined; she dressed badly; and the frizzling of her iron-grey hair into a fringe gave a tinge of commonness, which found its echo in the timbre of her voice.

"How do you do, Mrs. Morris?"

"How do you do, Mr. Stirling?"

The Squire was famed for his frank ease of manner among friends and tenants of whatsoever degree; but he seemed now cold and constrained. A look of displeasure was stamped on his brow; and it grew into a frown at the sight of a second girl, who had followed him in. With her the mother's hardness and commonness were reproduced, and the fringe was obtrusively prominent.

"Good morning," he said curtly to her, and then turned to the mother. "Winnie is not looking well."

"Not likely in this dismal hole," declared the last corner. Jane Morris was sure to thrust in a word, if she had the chance. "The Norfolk doctor said she never ought to be in a cold climate; and this is going to be cold enough in all conscience. He said she ought to go to the sea before next winter."

"It's dry and healthy here," Mrs. Morris put in.

Mr. Stirling turned from Jane. "How is Raye getting on?"

"Like a house on fire, he says," declared the irrepressible Jane.

Mr. Stirling put up one hand with a dignified gesture.

"Will you please allow your mother to speak for herself. Can you give me a few minutes in another room, Mrs. Morris?"

"There!" Winnie said with a sigh, as they disappeared. She went to the stiff old-fashioned sofa, from which she was seldom long absent. "Now you have driven him off!"

"Rubbish!" shortly answered Jane. "He and mother always have a business talk."

"What made you say that about the climate,—and about my going to the sea? It was like asking him to send me."

"Well, why shouldn't he? I wish he'd send you and me together. Anything to get away from this hole."

"We have no right to expect him to do things for us."

"I think we have. Mother saved Miss Stirling's life by her nursing. And everybody says he just lives for Miss Stirling."

"All those years and years ago!"

"That makes no difference. If it wasn't for mother he'd have no niece now. I think he ought to be grateful; and I don't see that he can do too much in return. He might just as well send you and me to Brighton for a month."

"Jane!—don't!—how can you? Don't speak so loud! And I can't think how you can talk so." The small delicate face flushed with feeling. "It is just because he has been so good to us—such a real friend—that I can't bear to think of asking him to do anything more."

Jane mumbled something. "I only know I can't abide the place," she added. "I'm sick of it."

"Why, we've not been here six weeks."

"It feels like six months," Jane yawned vociferously.

"You are always going into Lynnbrooke."

"Couldn't exist if I didn't. I just hate this farm."

Winnie lifted an entreating finger; and Jane sank into sullen silence. Beyond a shut door two voices alternated.

"I believe they're talking about us," muttered Jane. And she was not mistaken.

CHAPTER V

A Secret Agreement

MR. STIRLING had placed himself in the farmer's high-backed chair; and Mrs. Morris occupied one of cane, exactly opposite. Their positions seemed to be opposed, as well mentally as bodily. A displeased dent still marked the Squire's forehead; and his gaze was bent moodily downward. Mrs. Morris, looking not at him but at the wall, with hands resolutely folded, heard what he had to say. An odour of stale tobacco filled the air; for this was the farmer's "den."

"You see what I mean?"

"Yes—I see," she replied.

"For my niece's sake, I will allow no risks to be run." She knew that he might have added, "And for my own sake!"—and her lip curled. "Remember!—I am quite decided about this. If, through any carelessness, you allow suspicions to be awakened, you know the consequences."

"Yes," she stolidly repeated.

"I have been a good friend to Raye." He spoke in unconscious echo of Winnie's words.

"Yes, you have," she admitted. "But—"

"You must be content with that. I will go on being a good friend to him, so long as our agreement is strictly kept to. Once break it— and you know the consequences."

He was gazing at her, and her expressionless eyes met his.

"Yes, I know," she assented in a dull tone.

"Your income stops, and I have no more to do with Raye. You understand what that means—for the future."

"Yes, I know," she repeated.

"One item in our agreement was—that Raye should never come to this neighbourhood, without my express permission."

"You mean—he's never to see me?"

"I mean what I say. He is not to come here. If you wish to see him, you go elsewhere."

"Not even—once in the year! I've always had that."

"Not even once in the year. It is your own doing. If you had stayed in Norfolk, as I desired, you could have had him as before. Now you cannot."

"It's a bit hard on Raye—if he mayn't ever come to his own home."

"That is your affair. You have chosen."

Her face took an obstinate set.

"I couldn't help coming. I'm wanted here. I just felt I had to come."

"Under the circumstances, you ought to have felt that you had to stay away, considering—though I would rather not say this—all that I have done for you and yours. Remember—but for me you were penniless. Remember, too, that I was not bound. You had from the first no real claim upon me."

"I don't know as I see that," she muttered.

"Whether you see it or not, it is true."

"Anyway, when I promised I'd do as you wanted, I did say I might some day have to come here and look after my uncle. I don't forget that you've done a lot for us. But all the same, I had to come."

"Then you have to accept the consequences. When you wish to see Raye, it must be elsewhere. That is decided. I need not again remind you how much in Raye's future may hang upon this. One more point. You must keep Jane in order."

"I'm sure I don't know whatever I'm to do. She's off on her bike for hours together. I can't stop her. She aint like Winnie, always happy with a book. Jane likes lots of friends, and she don't trouble to tell me where she goes, nor what she does with herself."

The Squire's look was uncompromising.

"She's for ever on the go, wanting amusements. I don't know what's come over the girls nowadays. It's always amusement that they want,—not work."

"You must control her."

"I never could manage Jane, and that's the truth. She just goes where she chooses, and picks up whoever she comes across. It's her way."

"It is a great deal too much her way. She is becoming talked about. In Norfolk, however objectionable such behaviour might be, it did not matter to me personally. I will not allow it here."

"I don't see how I'm to stop her."

"You must find a way. Jane has to be kept in order." In a lower tone he added: "Do not make it necessary for me to take next year a step which I should be most reluctant to take—to refuse the renewal of your uncle's lease."

She was startled out of her stolid unconcern. "You wouldn't! It would kill him."

"I should regret extremely having to do it. But—he might have to choose between that and sending you all away,—or rather, sending Jane away. At any cost, I intend to guard my niece's happiness."

He could see that she swelled resentfully, and he stood up to say good-bye. No one, noting those two faces, contrasted and antagonistic, would have imagined how in the past their lives had been intertwined; not through any action of his own. The fact was known to themselves only; not even to her children.

They watched him from the sitting-room window, as he passed down the garden, and paused for a chat with the farmer; and Mrs. Morris observed—

"He's been making a lot of complaints of you, Jane. You've got to mend your ways."

"Much obliged!" Jane tossed her head.

"He says you're getting talked about in Lynnbrooke. You're always in and out there; and you're a deal too free and noisy with folks. He don't like that sort of thing."

Jane tossed her head again. She was extraordinarily unlike Winnie; not only by nature but by training, having been sent by her mother to a very third-rate school, and then having spent years with some distant cousins of her mother in Manchester; undesirable companions for any girl.

"He'll have to do without the liking. I'm not his humble slave—I can tell him that. Goodness gracious me, I'm not going to ask him what I may and mayn't do. He seems to think he owns our bodies and souls, because the land belongs to him."

"He's always so kind," Winnie put in reproachfully.

"Kind to you, if you like. You know how to come over him. He just hates me, and always did. He thinks of me as if I was scum beneath his feet." Jane's metaphor was mixed.

"It's your own fault," Mrs. Morris said shortly. "And if you don't look sharp, you'll get us all into trouble. I can tell you, he won't stand it. I know what he means. It's those Parkinses he don't like, that you're so thick with."

Jane snapped her fingers.

"I don't care that for him," she declared.

Unconscious of Jane's rebellious attitude, the Squire rode homeward; and half-way between Lynnbrooke and Lynnthorpe he came suddenly on Doris. She was seated meditatively by the roadside, her bicycle propped against the hedge. She was so engrossed she did not notice his approach till he dismounted.

"Are you coming to see Katherine? Is anything wrong with your machine?"

She glanced up with a brilliant smile. "Oh no, thanks. I'm only making a debating-club of myself. Question under discussion—Shall I go on, or shall I turn back?"

"Why turn back? Thomas shall see you home."

"Oh, thanks—but it's light so late now. Mother wanted me to cover some books before going out; and I wouldn't. It's an awful business—such a state as they are in. And I was vexed about something else too; so I started off without telling her. Ought I to give up and go back?"

"Is that necessary, now you have come so far?" He met the appeal in her face with a man's decisiveness. "Tell your mother I wished you to come."

"Thanks awfully—" and she sprang to her feet. "That will put it all right."

CHAPTER VI

Doris Lets Herself Go

KATHERINE STIRLING and her cousin, Hamilton, were seated together in the hall at Lynnthorpe; really its "living-room." It had an old oaken door opening on a wide terrace; deep window-seats; a huge fireplace; and antique furniture. The house was very old; and successive owners had reverently refrained from spoiling it by brand-new additions.

As usual, Hamilton was the talker, Katherine the listener. He loved a good listener; one who would submit to be convinced by his arguments; one who would not interrupt. Katherine was an adept at fulfilling this role.

He had talked for fifty minutes without a break; and he could very well have gone on for another fifty, had the Squire allowed Doris to turn homeward. Having laid down the law on foreign affairs, on home politics, and on the state of the money market, he proceeded to skim the fields of literature—if the word "skim" could be applied to any of his movements—and to recommend a well-thought-out course of geological study.

Katherine cared little for politics, less for the money market, least for ancient implements and extinct monsters. But she paid unwavering attention, because it was Hamilton who spoke. With many women the speaker matters far more than the thing spoken about.

The two were second-cousins and friends; not lovers. At least, Hamilton was not Katherine's lover, and perhaps never had been, though two or three years before this date some had looked upon him as tending that way. If so, he had made no further advance.

As for Katherine, he was and always had been for her the embodied type of all that a man should be. But she often told herself that she could not think of leaving her uncle to live alone; he so depended on her companionship. So perhaps she was in no great hurry for matters to ripen. It was enough for the present that Hamilton seemed to belong to her, consulted her, confided in her. She was placidly happy in the "friendship."

For Hamilton Stirling to "consult" anyone meant only that he wanted approval of what he had done. Since Katherine always did approve, he found in her what he wanted.

She was just thirty years old; and she looked her age, being pale, quiet, patrician to her very finger-tips. Many complained that she was proud and distant, and hard to know. Perhaps they were right. Perhaps she was proud—proud of her descent, of her blue blood, of her beautiful ancestral home, of her uncle. But if so, it was a humble and non-boasting type of pride; and she was also very shy, very self-distrustful; a not unusual combination.

Hamilton, now in his thirty-ninth year, possessed the typical Stirling outline of feature, which was even and regular. Somehow he managed to be less good-looking than Nature—to use a popular phrase—had intended. He had none of the elder Stirling's charm of manner. He was too rigid, too measured, too sure of himself, whereby he often provoked other people, who could not for the life of them see why they too might not be sometimes in the right.

But he never provoked Katherine; and that no doubt was partly why he so enjoyed her companionship. She always gave in to his views.

At the end of fifty minutes, having done with extinct monsters and underground fire-seas, he broke new ground. Katherine found him to be discussing Doris Winton, of whom she was fond. An unwonted thrill became audible in his voice, and he even flushed slightly,—a most unusual phenomenon. It might have ranked for rarity among some of the pre-Adamite phenomena which he had been describing.

Katherine, on the contrary, grew rather more pale; but she listened with her ordinary calm.

"Yes," she said. "You want—what is it?"

He showed a touch of displeasure at her inattention, and went over the ground again. He wished her to use her influence over Doris. That was the point; and Katherine had heard, but had doubted her own ears.

Doris Winton was a gifted and most attractive girl; but—this between themselves—certainly a degree lacking in self-control. He ran through the little gamut of her faults, suggesting that, if Katherine would kindly exert herself, those faults would soon cease to exist. The thing which struck Katherine unexpectedly, as with a physical blow, was that he talked as one who had a personal interest in the matter. Doris was to be improved and shaped—for him! He did not say this, but he implied it. He wished her to be trained and educated up to his level.

"I am afraid I have very little power over Doris," Katherine said. "But, of course, I will do what I can."

Of course she would; since it was Hamilton who asked it of her. And still more "of course" nobody should ever guess what this meant in her own life.

"Here comes Doris with my uncle," she remarked, turning to the window.

Hardly a greater contrast could have been found than between these two; Doris, all life and glow and high spirits; Katherine, colourless, still, and impassive.

Nobody noticed Katherine's look. She had much self-control; and one who is always pale may easily be a little paler than usual, without causing comment. Doris's vividness absorbed attention. She had not expected to find Hamilton here; and the encounter, just after Mrs. Winton's unwise suggestion, threw her off her balance. Whatever she really felt about him—and no one knew this less than the girl herself—she was flattered by his attentions. Things might have drifted a good deal further, unconsciously on her part, if the mother's heavy hand had not reduced the abstract to the concrete.

Doris only knew that her spirits, after descending to zero, rushed abruptly to tropical heat. She made no effort to restrain this new mood. There is a charm in being carried on the crest of a wave, reckless of rocks ahead; and she allowed it full swing. She had found a seat on an old carved chair, facing the three; and her cheeks were a pretty carmine with excitement, while the hazel eyes shone like stars. The slender hands lay ungloved and quiet, but she talked fast.

They listened seriously to her sallies. In the Stirling composition existed a total lack of the "saving sense of humour," though the Squire's sympathetic readiness to smile with those who smiled often took its place. But he was grave to-day, and Hamilton was slow as a tortoise to grasp a jest, while Katherine seldom attempted the feat.

"I didn't believe I could come, for mother wanted me to put fresh covers on a lot of old library books. Don't you just abhor handling books that have been pawed over by the grubbiest fingers in the place? If I had my way, I'd whisk them all into the nearest ash-pit. I shirked the work yesterday, and to-day I was wild for a spin—leaving dull care behind! So I eloped without permission; and half-way here a most awful fit of remorse came on. I had to sit down on the grass to fight it out. And Mr. Stirling found me there, and said I might come on, which I was just dying to do. It's lovely to have things settled for one, in the very way one wants."

The Squire smiled because he knew it was expected of him. Katherine did not hear; and Hamilton objected to feminine frivolity.

"And isn't it perfectly horrid when one wants to do a thing and conscience won't let one alone? I had set my heart on coming, and I did my level best to smother remonstrances. Lynnthorpe is always my haven of refuge, when the world gets out of gear."

"I have always imagined needlework to be a woman's proper refuge," Hamilton remarked, and she flashed round upon him.

"You haven't! Needlework! It's my purgatory. It's the bane of my existence. If ever I have a home of my own—" the words slipped recklessly out, and though with instant realisation her colour deepened, she went on—"I'll never darn another stocking in my life. Don't I wish I could set a dozen men for a whole day to patch and mend? They wouldn't prescribe needlework again, I can tell them, as a sedative! Besides, I don't want sedatives. I want champagne. The only sort of needlework I ever found endurable is trimming hats. I should like to trim a new one for myself every week, and to give the old ones away. That would be jolly."

Hamilton disapproved alike of extravagance and of feminine slang, which she knew.

"A hat doesn't take long, when one is in the mood. Don't you love doing things when you're in the mood, and don't you hate doing them when you're out of the mood?" She glanced at Hamilton, and he tried to insert a remark about not being the victim of impulse, but she gave him no loophole, and rattled on.

"I wonder whether, if I waited long enough, I should ever be in the mood for handling dirty library books. But, of course, I shouldn't. It's too hopelessly against the grain. Oh, yes, I had your letter— thanks awfully." She suppressed a glimmering smile. "And I'll keep the list of books that you want me to read; though I don't believe I shall ever manage to wade through them. Geology is so fearfully dry. It's history that I love; and poetry; and languages; and really good novels. Not science. You don't care for novels, I know. You only care for chemical combinations and explosive substances, and old bones and stones, and labelled specimens, and flints and arrowheads."

Katherine was silently indignant that the girl could laugh at Hamilton. He tried to defend himself; but for once the inveterate talker was over-matched. Doris did not raise her voice, but she poured steadily on like a babbling stream.

"Oh, I know!—I know! Old bones mean a lot; and everybody ought to be scientific. But everybody isn't; and I don't care a hang for rows of specimens. One wants something lively in a place like Lynnbrooke. It's always the same thing over and over again here. A weird old body marches up, born in the year one, and says: 'How do you do?—and is Mrs. Winton quite well?—and how busy the dear Rector must be!' Or perhaps from somebody weirder still it's: 'How's your Parr and your kind Marr?—and what good weather!' Or else: 'Deary me, Miss, I've got the brongtipus in my throat, that bad, you can't think!' And if it's one of the parish ladies—we're all old ladies and parish ladies!—it is: 'My dear, do you think you could get me some more soup-tickets?— and are there a few club-tickets to spare?' Or else a bit of gossip: 'I suppose it's quite true that John Brown is going to marry Lucy Smith. Dear, dear me, what a sad look-out for those poor young things!'"

She had slid into mimicry, giving one voice after another with delicate exaggeration. The Squire smiled again absently; while Hamilton's rigid face betrayed his disapproval. Yet even in his annoyance he realised, more vividly than before, his growing captivity to this eager girl, with her slim grace, her warm colouring, her brilliant eyes.

She did not represent his ideal wife. The life-companion of Hamilton had always been, as pictured by himself, after a different model— refined, ladylike, self-controlled; a dove-like being, placid and meek, submissive and gentle, with manners full of repose, a tender smile, an infinite capacity for listening, and no pronounced opinions of her own.

Doris was neither meek nor submissive, neither reposeful nor dove-like. Her laugh, though ladylike, could hardly be called low; and she much preferred, at least in her present mood, hearing her own voice rather than his.

He had not seen her like this before. She sat flashing nonsense at one and another, reckless of what might be thought. As a child, and still more as a school-girl, home at intervals for the holidays, he had generally ignored her existence. It was only during the last few months that she had dawned upon his consciousness as a distinct personality.

"How I should love to be in London!" This was a fresh divergence. "Always to be on the go, and seeing fresh people, and having a good time." Her words recalled Mrs. Brutt to the Squire. "I detest a humdrum existence; and nobody can deny that Lynnbrooke is awfully humdrum."

Tea coming in made a diversion; and when it was over Doris spoke of going.

"I really mustn't stay late, for mother hasn't the dimmest notion where I am; and those wretched books have got to be done. No need to send anybody with me, Katherine. I shall go like the wind, and get in long before dark."

Hamilton, with his air of disapproving gravity, offered himself as escort.

"Thanks awfully, but please don't. I'd rather not. I hate to be a bore; and you know you meant to stay here for hours. You and Katherine always have such oceans to talk about."

Katherine betrayed no shrinking under the thrust, which was not meant to be a thrust. Hamilton held to his point, and they started together.

CHAPTER VII

The Cycle Ride

ON the way home Doris's barometrical conditions underwent a change. Excitement had vanished; chatter ceased.

The talkative mood over, she became conscious of having given vent to a good deal of nonsense. And people seldom talked nonsense at Lynnthorpe. The atmosphere was uncongenial; in fact, Lynnthorpe was the wrong place for nonsense of any sort, good, bad, or indifferent.

From earliest childhood the doctrine had been impressed upon Doris that, when with any of the Stirling family, she must be on her best behaviour, must speak in her gentlest tones, must use her mildest adjectives. Perhaps she had never before so flagrantly run in the teeth of these rules.

So far as regarded Hamilton she did not mind. She had meant to shock him—a little—and if she had succeeded, so much the better. But to shock Mr. Stirling and Katherine was like shocking Royalty; a thing not to be got over. She determined that, next time she went to Lynnthorpe, she would carefully wipe out to-day's impressions by an elderly decorum, better suited to the dignified surroundings. She loved Katherine with a mild and flameless affection; and she looked upon the Squire as the ne plus ultra—the ultima thule—of all that a man should be. He was in her girlish eyes the embodiment of masculine perfection; and from judgment in that direction existed no appeal.

Besides these uneasy recollections, she was annoyed with Hamilton for his insistence in seeing her home. It was an annoyance entirely due to her mother's action. Possibly she might have been disappointed had he not insisted.

He rode his bicycle as he did most things, too rigidly; while her lissom figure swayed with easy grace to each curve in the road; and she flew along at a speed which he tried to check by holding back. In vain; for she shot ahead, glanced back, and gave him a wicked little farewell nod. He had to put on speed to overtake her.

She was thinking hard. She knew that he objected to rapid bicycling for women; and she was bent still on crossing him. Mrs. Winton had seemed to take it for granted—or so Doris imagined—that he only had to speak to be accepted. Her pride was up in arms. Nobody should suppose that she sat meekly, with folded hands, awaiting permission to be his.

She might marry some day. She might even marry Hamilton Stirling. It was not an impossibility. All things considered, she rather favoured the notion, as a dim and distant prospect. She enjoyed feeling herself the object of somebody's attentions. It gave her a touch of prestige. Moreover, she had a supreme admiration for intellect in every form; and thus far Hamilton was about the best embodiment of intellect that she had come across.

Or if not, he appeared so to her; and at least he thoroughly believed in himself. Doris was not unwilling to accept him at his own valuation. He had graduated with moderate honours, and had elected to enter no profession, but to devote his life to the pursuit of science. Since he had enough to live on, he could do as he chose. His mother objected, but not strenuously, being glad to keep him at home. Friends opposed the decision; but Hamilton, with calm indifference, pursued the even tenor of his way.

He was not an energetic man, yet none could call him idle. He read a great deal, belonged to divers learned societies, and wrote much, with the avowed intention of becoming, one day, a scientific luminary. Doris decided that, if ever she did marry him, he should write something that would stir the world. She would be his helper, his inspirer. The idea was fascinating; and she failed to remember the disappointed ambitions of a certain "Dorothea," great in fiction,— aspirations like in kind.

While so cogitating she abstained from remark, waiting for him to begin. But he too was silent. He could not get over her conduct that afternoon, or the coldness with which she had so far received his confidential letter.

It dawned upon her that, if he had made up his mind not to take the initiative, no power on earth would make him. There was a spice of obstinacy in his composition.

"How nice it was of you to write and tell me about that article of yours being accepted!" she said approvingly.

He spoke in chilling accents. "I supposed that you felt no interest."

"But I do. Why, of course I do. I think it's most frightfully jolly that you are really going to get into print at last. Quite too delicious, I mean,"—as she recalled his dislike to girlish slang. Perhaps she had shocked him enough for one day. "And now they've taken one paper, they'll take lots more, of course. How soon is it coming out?"

"Probably in a month or two." Curt still.

"Odd—isn't it?— that when a heap of old bones are found in a cave, people can put them together—like a jig-saw puzzle—and settle all about the sort of creatures that used to live there?"

Hamilton smiled a superior smile; and Doris's long lashes twinkled an acknowledgment.

"But sometimes the very cleverest men do make mistakes—and call the old bones by wrong names."

This "drew" Hamilton, as she intended; and he launched into an elaborate defence of scientists in general. Very much to his surprise, he found her remark to be no random shaft. He had discovered before now a cheerful uncertainty about Doris's mental attributes, which kept him continually on the stretch. You never could foretell what she would produce next from her hidden laboratory. Any amount of feminine inconsequence might come to the fore; but, when least expected, she would send an arrow straight to the mark.

"Oh, yes, of course. Nobody makes mistakes on purpose. But there was a bone somewhere, which all the savants declared was a human bone. And they proved a heap of things from it, about how long man had been living on earth. And in the end it turned out to be only a bear's bone; so all the wonderful arguments went to smash. Father told me; and I think he was rather pleased. Only, he was afraid a great many people who heard of its being a man's bone, never were told that it was all a mistake. And he said we should never be in a hurry to draw conclusions of that sort, because Science is a structure built upon discarded blunders." She quoted the words with empressement.

Hamilton had intended to give, not to receive, information. He would not for the world confess that he had forgotten the incident in question; for a man whose cue it is to know everything naturally does not like to be caught napping. He was conscious of relief when she went back to his article.

"Would you care to read it in proof?" he asked.

"May I, really?" Her face flashed into brilliant interest. "I've never read proof-sheets. May I help you to correct the mistakes?"

His smile showed doubt of her powers. "I have it here," he remarked, and she was on the ground with a spring. Impetus carried him ahead; but he wheeled, came back, and dismounted.

"You should not jump off in that wild way. It is unsafe."

"Oh, I often do, going full speed. I always come down right way up. Do show me the proof. It's light enough."

Her eagerness gratified him. They stood at one side of the road, and red sunset gleams, shining through a thin veil of trees, found a reflection in her sunny face. He fished a small packet out of its retreat, and she scanned the long slip with delight, spotting instantly two slight printer's errors which had escaped his notice. He pencilled both; and then she pitched on another mistake, this time grammatical, not the printer's but Hamilton's own. He was chagrined, finding it impossible to deny the force of her contention; and—"I will consider it"—was all he could bring himself to say. He had expected praise, not criticism.

A motor car rushed by, covering them both with dust. Doris was too much absorbed to notice it.

"You couldn't let that stay. Think—how it would sound!" She read the sentence aloud with exaggerated emphasis. But the next instant she was soothing his ruffled sensibilities. "How you must love to see yourself in print! I should like it of all things. To feel that one has power over other people's minds—to feel that one may help them, and make them better! Don't you see?"

She met a non-comprehending glance. What Hamilton did see at that moment was Doris herself. He wondered that he had been so slow to realise her charm. Yes—she was the woman for him—with just a little shaping and manipulation. He was glad that he had spoken to Katherine.

"Don't you see?" she repeated, her hazel eyes deepening. "I think—I do really think—I would rather have that power than any other. Only, of course, one would have first to understand more of life."

But life in Hamilton's eyes wore a simple aspect, not in the least perplexing. He was always sure of his own standing, and he could look upon no landscape from his neighbour's position.

"People seem so oddly arranged for—so queerly placed!" She forgot the printed slip in her hand, as she gazed dreamily away from him and toward the reddening west. "Born artists set to darn socks; and born musicians set to sweep crossings; and born idiots set to govern nations. People having to live with just those others who go most frightfully against the grain,—and having to do just exactly the work that they most detest and can't—really can't—ever do well. Why mayn't people always be with those that suit them—and do the things they like doing?"

His slower mind followed her gyrations with difficulty. There was in him no gift of instant grip and swift response, that most valuable of assets in dealing with other minds. He could talk for an hour at a time, but always in certain grooves. He could not catch up another's line of thought, and make it for the time his own. Before he could decide what to say, she was off on a fresh tack.

"I'm so glad you're going to get this paper out. It's a beginning. But you won't stop there, will you? You won't only write articles on geology and that sort of thing—will you? Not only about the bones of poor old dead people, who lived such ages and ages ago. Can't you sometimes write what would help the people who are alive now—something that will tell them how to make the best of their lives? Do you see what I mean? You don't mind my saying it? So many people seem to be all wrong—put in the wrong place, and having the wrong sort of work to do. And if you can write, couldn't you help them—say something to show them how to get right?"

Her shining eyes were full upon him; and he had an uneasy consciousness that she was asking of him that which he was powerless to give. The feeling of incapacity was unwelcome; and he took refuge from it by beginning to quote in his measured tones—

"But that has been said before," she interrupted hastily. "Everybody knows it; and I think now we want something new. Couldn't you give us something fresh? Couldn't you think it all out, and give it us in words that haven't been said before?"

She read displeasure in his look.

"Besides—the trivial round never does furnish me with all I want. I detest common everyday tasks. They are so stupendously dull. Well— it can't be helped. We had better go on."

She in her turn was vexed with his lack of sympathy. She had opened out a corner of her real self, and had met with a rebuff. She gave him back his proof, and was off like an arrow, sweeping down the long gentle incline. Hamilton kept pace with her, but he counted the speed unsafe for a woman; and at the bottom of the hill he told her so. She glowered all the rest of the way. But her anger was not unbecoming. Most people, out of temper, look their worst. Hamilton was fain to admit to himself that she looked her best—reticent, dignified, with a geranium-tint in her cheeks, and a smouldering glow in the deep-set eyes which turned them nearly black.

More and more he was conscious of a growing thraldom. At some future day he would certainly make this girl his wife. It did not occur to him to say "If!" But some training first was desirable; and he hoped great things from Katherine's gentle influence. He had never so distinctly disapproved of Doris as to-day; and he had never before found himself so definitely in love with her. The combination was a trial to his well-balanced mind.

CHAPTER VIII

Mrs. Brutt Suggests

AT a side-table in the morning-room, with its green carpet, faded green curtains, and air of general usefulness, Doris sat at work over the library books. Murmured interjections of disgust, on behalf of her dainty finger-tips, broke from her, as she handled covers which had passed through the "grubbiest" village grasps. She touched them gingerly.

Behind her, at the centre table, stood Mrs. Winton, cutting a roll of coarse flannel into lengths. No gingerly touches here, or wasted moments. Mrs. Winton was an expert with her scissors.

Neither had spoken for some time. Thus far, no more had been said on the vexed question of Hamilton Stirling's letter; but Doris knew that her refusal to show it was not forgiven. An atmospheric disturbance prevailed. More than once she had said to herself, "I'd rather have a good explosion, and have done with it!"

Yet somehow she had not named her encounter with Hamilton. In a general way she would have mentioned it freely. But Mrs. Winton's question had produced an uncomfortable consciousness; and she could not now talk of him quite naturally. So she took refuge in not speaking of him at all.

The silence came to an end.

"You did not tell me that you had seen Mr. Hamilton Stirling yesterday."

Doris pasted with diligence.

"No, I didn't. Why should I? He's always in and out there."

"You gave me the impression that you had seen only Mr. Stirling and Katherine."

"I never said so."

"One may convey a wrong impression without any actual untruth." Mrs. Winton did not speak unkindly, but she was troubled; and she found herself at a disadvantage, facing Doris's back. "It was not quite like you."

Doris turned hastily.

"Mother—I can't help people's impressions. I simply said nothing, because—"

Mrs. Winton waited in vain for the end of the sentence.

"He was not only there, but you and he bicycled back together. Mrs. Stirling came in an hour ago to speak to me. She was motoring back from a party with some friends; and they saw you and him in the road, standing and talking, as if—"

"As if—what?" proudly. For this sentence, too, remained unfinished.

"She was much surprised that I had heard nothing. Why did you not tell me?"

"Because I knew, if I did, I should be badgered half out of my senses." Doris returned to her work, pasting with hands that shook a little.

"You never used to speak to me in such a tone." Mrs. Winton was really hurt. "I cannot think what has come over you lately. Mrs. Stirling evidently thinks that you said or did something which Hamilton did not like. She wanted to know from me what had passed, since she could not get him to explain."

"I don't see that it is any business of hers."

"No business of his mother's!" Mrs. Winton moved two steps nearer, and examined the sleeve of Doris's blouse. "You should get out this grease-spot."

"It's not grease!" The girl quivered under Mrs. Winton's handsome but ponderous hand.

"Certainly it is grease. You must see to it. But about Hamilton Stirling—I want to give you a word of warning. If you go on as you are doing now, you will end by driving him away. He is not a man to stand rebuffs."

"Horrid man! Let him go, and welcome! I don't want him to come bothering me."

"I don't think you mean what you are saying."

"Yes, I do. He puts me out of all patience."

Doris had swung round, after a night's rest, to a mood many degrees less favourable to her admirer. "And I can't stand being worried about him, mother. If I liked him ever so much—and I don't—at least I think I don't—that would be enough to turn me against him. All I want is to be let alone."

She flung a book down tempestuously, and vanished from the room, leaving Mrs. Winton to uneasy reflections.

That the mother should be solicitous for her child's happiness was only natural; and she honestly believed that marriage with Hamilton would ensure that happiness. True, some people counted him a bore, and others reckoned him something of a prig; but he was always agreeable to Mrs. Winton herself. She had watched his attentions from the first with approval; but had been often exercised over her daughter's erratic changes of mood. One day Doris would be all smiles and graciousness; another day she would hardly vouchsafe a glance in his direction. One day she would welcome a letter from him with barely-veiled delight; another day she would toss it aside with a disdainful—"Old bones again! What a bother!"

To Mrs. Winton this meant real anxiety. How to set things right she did not know; and it never occurred to her that the sensible plan was to do nothing. She had yet to learn the wisdom, in such affairs, of holding patiently aloof.

Doris, meanwhile, catching up a garden hat, made her way to Clover Cottage. It was by no means the first time that she had fled for comfort, after a passage-at-arms, to her new crony, Mrs. Brutt. She did not mean to betray aught that had passed. She only wanted to be soothed and made happy again. But once in the power of that astute widow, she let slip a good deal more than she knew. Mrs. Brutt had a gift for worming things out of people, without their consent.

It was nice to sit on a low chair, close to the elder lady, beyond the region of home-worries; to feel kind and approving eyes bent on herself; to have no fear of fault-finding; to be listened to with affectionate attention; to be sympathised with compassionately.

"Poor dear child! Yes, I quite understand. You have been so busy, have you not? And you are quite tired—quite jaded—with it all."

Doris disclaimed fatigue. Yet a wonder crept over her—was this sense of discontent with her little world, this craving to get away and to live a different life, really tiredness? She began to pity herself.

"What with classes—meetings—district—shoe-club—library—parish accounts—errands—"

Truth compelled a protest. Some of these belonged to winter only; some not to her at all.

"So uncomplaining! Such a brave spirit! Not much leisure for your own concerns, poor dear child!"

"Well—of course—" admitted the girl.

"Yes, of course—I know. And I can so sympathise with you in your love of reading. I adore books."

"Mother seems to think it a waste of time to read much in the morning."

"Ah—true—yes—non-intellectual!" murmured the other, not inaudibly. "Poor dear child. But, really you know, it is most necessary that you should have some recreation—apart from the time for study, which— with your mind—is so needful!"

"I go to lots of tennis-parties and afternoon teas," Doris laughed. "No end of them. You mustn't think I don't have plenty of fun." Honesty again compelled this.

Mrs. Brutt surveyed her visitor with a meaning gaze.

"Tennis-parties! Yes. And afternoon teas! Yes. That sort of thing. Just the country round. Yes. My dear, I wonder if you half guess what a bewitching creature you are. Positively, neither more nor less than bewitching. Not at your best to-day, perhaps,—you have been worried, and that tells. But if you could see yourself—sometimes!"

Doris blushed with pleasure.

"Yours is a sylph of a figure. And there is the sweetest little dimple when you smile. Yes—just there—" with a touch. "Your play of feature is simply charming. And your eyes are a true hazel—a blending of green and yellow and brown and grey. Now I have made you laugh. I like to see you laugh. It suits you to get excited. You should let yourself go oftener—give the reins, you know, and not wait to think what anybody may say."

"But when I do, I'm always sorry afterwards. I'm sure to say the wrong thing."

Mrs. Brutt ignored this.

"I only wish I had you in London," she said pensively. "Or—better still—abroad. Meeting all sorts and kinds of people, and making no end of new friends. It would do you such good. And you would be a success, Doris."

"Should I?"—wistfully.

"No doubt of it—with your figure,—your eyes—your complexion. Such a pretty creamy-white, and such a delicate rose-carnation. And you hold yourself well—you have such a natural air and pose. And you talk well, too. Oh, you would take everybody by storm. I know!"

She launched into a detailed description of life in foreign towns; of going from hotel to hotel, finding always delightful people, meeting with the élite of society. Incidentally she gave her hearer to understand that her own past career had been one long series of social triumphs, and that her present retired existence formed a dismal contrast. She piled her colours massively; and Doris's "daily round" could hardly fail to wear a dingy hue, seen alongside.

"You should get your father to let you travel for a few months. Not, of course, alone, but with some older friend. Somebody who could take you about, and introduce you to the right people. Everything depends upon that."

"I should love to go with you," Doris said warmly. "But—no chance of such a thing!"

"My dear, I should love nothing better. Well—we shall see. Sometimes impossible things become possible. Who knows? Are you going to luncheon at Lynnthorpe on Friday? You had better drive there with me, unless you prefer your bike."

Doris thought she would prefer to drive. She was disinclined for another tête-à-tête with Hamilton quite so soon. She went home, elated at having been made much of, and having become in her own eyes something of a martyr.

Mrs. Brutt suffered from no twinges of conscience. On the contrary, she felt pleased with the progress made. Lynnbrooke was dull; and she was bent upon going abroad in August. She liked the notion of a young and pretty girl by way of companion; one whom she could show off, and who would have no voice in arrangements. An older person might be troublesome.

In a certain allegorical tale, published long ago, a pilgrim, named "Good-Intent," came across a company of men, groaning under the weight of heavy chains. They had not discovered their miserable condition, till some officious passer-by had taken the trouble to point it out; whereupon, cheerfulness gave place to melancholy. That the chains existed only in their fancy, as a result of "suggestion," did not lessen their actual unhappiness.

Mrs. Brutt was doing the work of that officious passer-by. She was pointing out to Doris fetters in her life, which till then had not seemed to be fetters.

Of course the girl had trials; who has not? Of course she had to do things which she did not enjoy doing; who, again, has not? But though the fetters might not be a matter of pure imagination, their weight could be very much exaggerated.

Mrs. Brutt gave to vague dissatisfaction a definite voice. She magnified small frictions into serious troubles. Doris was warm-hearted, impressionable, easily swayed; and the elder lady knew how to manipulate such materials.

Not that she meant to do harm. Few people do. All she wanted was to bring about her own ends; to amuse herself, to make time pass pleasantly. She was kind-hearted, and by fits and starts she would go out of her way to help others. But in the main hers was a self-seeking nature.

Theoretically she knew little about the force of suggestion; but practically she was an adept in the use of that weapon. This is always possible. A duck may be an excellent swimmer, with no understanding of the theory of swimming.

Probably few of us grasp the tremendous potency of "suggestion," as exercised by one mind over another. Half the temptations that meet us may be simply the whispered "suggestions" of evil spirits. Half the helpful and comforting thoughts which arise in our minds may be the murmured "suggestions" of angels.

CHAPTER IX

Sudden Silence

FRIDAY'S luncheon was in full swing; and Mrs. Brutt felt miserable. She loved to be the best-got-up woman in a room. But to be wrongly got-up is another matter.

She had come in her most imposing grey silk, topped by a toque fit for Hyde Park in the month of May. And she found rural simplicity to be the order of the day.