American Nights Entertainment

Grant M. Overton

American Nights

Entertainment

Grant Overton

By GRANT OVERTON

About Books and Authors

AMERICAN NIGHTS

ENTERTAINMENT

WHEN WINTER COMES

TO MAIN STREET

THE WOMEN WHO MAKE

OUR NOVELS

Fiction

ISLAND OF THE INNOCENT

THE ANSWERER

WORLD WITHOUT END

THE THOUSAND-AND-FIRST

NIGHT (In Preparation)

American Nights

Entertainment

BY

GRANT OVERTON

New York, 1923

D. APPLETON & CO. GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & CO. CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

COPYRIGHT, 1923,

BY GRANT OVERTON

First Printing, September, 1923.

Press of

J. J. Little & Ives Company

New York, U. S. A.

Bound in Interlaken-Cloth

This Book

IS DEDICATED TO BOOKSELLERS

AND BOOKREADERS EVERYWHERE

BY THE AUTHOR AND THE PUBLISHERS

WHO HAVE JOINED IN ITS PRODUCTION

Preface

THIS book is written because of the rapid spread of the habit of reading books, developing in its march an interest in the personalities of authors. Indeed, the existence of this book is an evidence of the quick contagion of the book-reading habit, since four publishing houses have joined to make possible the pages that follow.

Few developments of the early part of this century are more encouraging than the new attention to books. The increase in book stores, the very large increase in the number of books sold, the multiplication of libraries and their great patronage, the success of new book review pages and periodicals—all are signs of the change that has come about in recent years, and perhaps especially during and since the war of 1914-18.

And in a narrower department, no development of recent years has borne a more cheerful promise than the resolution of four publishers to associate themselves in an enterprise the disinterestedness of which the reader is invited to assess for himself.

The entire responsibility for the estimates and opinions offered (where they are not directly attributed) is mine. I have tried to tell the truth, use my imagination legitimately, and observe good taste without the sacrifice of valuable insights into character and work.

For example, in addition to biographical facts, in themselves often unenlightening, I have usually tried, as in the account of Mr. Galsworthy, to disclose the personality so carefully (albeit high-mindedly) withheld from the writer’s books. Again, as in the chapter on Joseph Conrad, aside from the effort at novelty and freshness of interest by the device of adopting Conrad’s own Marlow as the narrator, I have made bold to set down some facts never before printed and not in the least generally known, because they seem to me a side of the picture that it is wrong to obscure.

The wealth of material spread before me has made the task of selection exceedingly difficult, and I cannot pretend to be satisfied with what I have chosen in the light of my knowledge of what has had to be left out. I owe a grateful acknowledgment to the publishers and to individuals in the several publishing houses for their generous assistance.

1 August, 1923.

Grant Overton.

Contents

| 1 | MR. GALSWORTHY’S SECRET LOYALTIES, 13 |

| 2 | THE MAGIC CARPET, 34 |

| 3 | A BREATHLESS CHAPTER, 51 |

| 4 | IN THE KINGDOM OF CONRAD, 64 |

| 5 | THE DOCUMENTS IN THE CASE OF ARTHUR TRAIN, 91 |

| 6 | THE LADY OF A TRADITION, MISS SACKVILLE-WEST, 102 |

| 7 | HAROLD BELL WRIGHT, 119 |

| 8 | “AH, DID YOU ONCE SEE SHELLEY PLAIN?” 139 |

| 9 | ALICE IN AUTHORLAND AND PENROD’S FIVE-FOOT SHELF, 157 |

| 10 | THE MAN CALLED RALPH CONNOR, 178 |

| 11 | HERE, THERE AND EVERYWHERE, 189 |

| 12 | TOTALLING MR. TARKINGTON, 217 |

| 13 | A PARODY OUTLINE OF STEWART, 239 |

| 14 | MISS ZONA GALE, 248 |

| 15 | FOR THE LITERARY INVESTOR, 255 |

| 16 | NATURALIST VS. NOVELIST: GENE STRATTON-PORTER, 270 |

| 17 | POETRY AND PLAYS, 293 |

| 18 | LOST PATTERNS, 313 |

| 19 | JOSEPH C. LINCOLN DISCOVERS CAPE COD, 321 |

| 20 | EDITH WHARTON AND THE TIME SPIRIT, 345 |

| 21 | THE UNCLASSIFIED CASE OF CHRISTOPHER MORLEY, 363 |

| 22 | THE PROPHECIES OF LOTHROP STODDARD, 380 |

| INDEX, 387 |

Portraits

JOHN GALSWORTHY, 15

JOSEPH CONRAD, 65

ARTHUR TRAIN, 93

V. SACKVILLE-WEST, 103

HAROLD BELL WRIGHT, 121

BOOTH TARKINGTON, 219

DONALD OGDEN STEWART, 241

JOSEPH C. LINCOLN, 323

EDITH WHARTON, 347

CHRISTOPHER MORLEY, 365

American Nights

ENTERTAINMENT

1. Mr. Galsworthy’s

Secret Loyalties

i

IN the autumn of 1922 New York began to witness a play by John Galsworthy, called Loyalties. Not only the extreme smoothness of the acting by a London company but the almost unblemished perfection of the play as drama excited much praise. Because, of the two principals, one was a Jew and the other was not, with consequent enhancement of the dramatic values in several scenes, it was said (by those who always seek an extrinsic explanation) that Loyalties simply could not have avoided being a success in New York. The same type of mind has long been busy with the problem of Mr. Galsworthy as a novelist. It read The Man of Property and found the book explained by the fact that the author was a Socialist. Confronted with The Dark Flower, it declared this “love life of a man” sheer sentimentalism (in 1913 there was no Freudianism to fall back on). And the powerful play called Justice was accounted for by a story that quiet Mr. Galsworthy had “put on old clothes, wrapped a brick in brown paper, stopped in front of a tempting-looking plate-glass window” and let ’er fly. On being “promptly arrested,” he “gave an assumed name, and the magistrate, in his turn, gave Galsworthy six months. That’s how he found out what the inside of English prisons was like.”

A saying has it that it is always the innocent bystander who gets hurt; but the fate of the sympathetic bystander—and such a one John Galsworthy has always been—is more ironic. That peculiar sprite, George Meredith’s Comic Spirit, reading all that has been written about Galsworthy would possibly find some adequate comment; but Meredith is dead and the only penetrating characterisation that occurs to me is: “Galsworthy’s the kind of man who, if he were in some other station of life, would be a splendid subject for Joseph Conrad.”

In the middle of Loyalties a character exclaims: “Prejudices—or are they loyalties—I don’t know—criss-cross—we all cut each other’s throats from the best of motives.” Well, in a paper written in 1917 or earlier and included in their book, Some Modern Novelists, published in January, 1918, Helen Thomas Follett and Wilson Follett, discussing Galsworthy’s early novels put down a now very remarkable sentence, as follows:

“Mr. Galsworthy does not see how two loyalties that conflict can both be right; and he is always interested in the larger loyalty.”

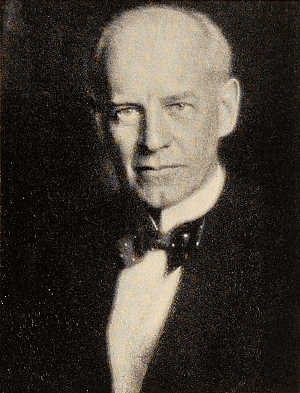

© Eugene Hutchinson

JOHN GALSWORTHY

So interesting and significant a statement, buried as seed, might easily sprout as novel or play. I have no atom of evidence that Mr. Galsworthy ever saw the comment; but if he read it and forgot (buried?) the words, then Loyalties was written in their effectual disproof. For in this drama, as in all his novels, as in all his other dramas, Mr. Galsworthy is constantly seeing and portraying how conflicting loyalties both are right; he is never interested in the larger loyalty and cannot keep his eye on it through consecutive chapters or through a single act; he is forever presenting the two or more sides and taking none. He once said: “I suppose the hardest lesson we all have to learn in life is that we can’t have things both ways.” He should have added:“—and I have never learned it!”

ii

“Learned,” of course, in the sense of “accepted,” of becoming reconciled to the fact. It did not need Mr. St. John Ervine to tell us that “Mr. Galsworthy is the most sensitive figure in the ranks of modern letters”; for of all modern writers the author of Loyalties and The Forsyte Saga is the most transparent. He is transparent without being in the smallest degree luminous; he refracts, but he does not magnify—a prism through which we may look at society.

Compare him for a moment with Mr. Conrad. Mr. Conrad is by no means always transparent; his opacity is sometimes extraordinary, as in The Rescue; and yet from the midst of obscure sentences, like a gleam from those remarkably deep-set eyes, something luminous will shine out, both light and heat are given forth. “In a certain cool paper,” explains Galsworthy, “I have tried to come at the effect of the war; but purposely pitched it in a low and sober key; and there is a much more poignant tale of change to tell of each individual human being.” But even when telling the more poignant tale, as in Saint’s Progress, the coolness is noticeable, like the air of an April night; the key is still sober, pitched low; and the trembling passion of a melody proclaimed by violins is quickly muted. Such is his habitual restraint, so strong is his inhibition, that when we hear the orchestral brasses, as we do once or twice in Justice and Loyalties, it shocks us, like a rowdy outburst in a refined assembly or a terse sentence in Henry James. But it is nothing, nothing. Mr. Galsworthy has momentarily achieved a more perfect than usual transparency; he has suddenly surrendered to the pounce of another of those multitudinous loyalties which give him no peace and the secret of which, except for its continual disclosure in his works, he would most certainly carry with him to the grave.

For he does not talk. No! “You are nearer Galsworthy in reading his books than in a meeting.” Another keenly observant person summed up Galsworthy’s conversational resources in the one word: “Exhausted!” St. John Ervine: “Whatever of joy and grief he has had in life has been closely retained, and the reticence characteristic of the English people ... is most clearly to be observed in Mr. Galsworthy.... How often have we observed in our relationships that some garrulous person, constantly engaged in egotistical conversation, contrives to conceal knowledge of himself from us, while some silent friend, with lips tightly closed, most amazingly gives himself away. One looks at Mr. Galsworthy’s handsome, sensitive face, and is immediately aware of tightened lips!... But the lips are not tightened because of things done to him, but because of things done to others.” Mr. Galsworthy, in a personal letter: “The fact is I cannot answer your questions. I must leave my philosophy to my work generally, or rather, to what people can make out of that work. The habit of trying to tabloid one’s convictions, or lack of convictions, is a pretty fatal one; as I have found to my distaste and discredit.” He conducts his own cross-examination, in new books, new plays. He acknowledges, with quiet discontent, the claims upon his sense of loyalty of a dog, a jailbird, two “star-crossed lovers,” the wife of a possessive Forsyte, a De Levis unjustly used. His pen moves, with a bold stroke, across the paper; another secret is let out; his lips tighten. He is serene and indignant and completely happy.

Why not? “My experience tells me this: An artist who is by accident of independent means can, if he has talent, give the Public what he, the artist, wants, and sooner or later the public will take whatever he gives it, at his own valuation.” And he speaks of such artists as able to “sit on the Public’s head and pull the Public’s beard, to use the old Sikh saying.” Nothing else is worth while—for an artist. “The artist has got to make a stand against being exploited.” But if the artist should exploit himself, or anything more human or individual than that impersonal entity, the Public, Mr. Galsworthy’s mouth would become grim again; his loyalty would be forfeited, I think. There might be a larger cause, but his concern would be with the other fellow. And however hard you might press him for a verdict, he would bring in only a recommendation for mercy.

iii

The Galsworthys have been in Devonshire as far back as records go—“since the flood—of Saxons, at all events,” as John Galsworthy once put it. His mother came of a family named Bartleet, whose county for many centuries was Worcestershire. The boy, John, was born in 1867 at Coombe, in Surrey. “From the first,” continues the anonymous but authorised sketch I am quoting, “his salient characteristics were earnestness and tenacity. Not surprisingly brilliant, he was sure and steady; his understanding, not notably quick, was notably sound. At Harrow from 1881-1886 he did well in work and games. At New College, Oxford, 1886-1889, he graduated with an Honour degree in Law. After some further preparation he was called to the bar (Lincoln’s Inn) in 1890. It was natural he should have taken up the law, since his father had done so. ‘I read,’ he says, ‘in various chambers, practised almost not at all, and disliked my profession thoroughly.’

“In these circumstances he began to travel. His father, a successful and unusual man in both character and intellect, was ‘not in a position to require his son to make money’; his son, therefore, travelled, off and on, for nearly two years, going, amongst other places, to Russia, Canada, British Columbia, Australia, New Zealand, the Fiji Islands, and South Africa. On a sailing-ship voyage between Adelaide and the Cape he met and became a fast friend with the novelist Joseph Conrad, then still a sailor. We do not know whether this friendship influenced Galsworthy in becoming a writer; indeed, we believe that he has somewhere said that it did not. But Galsworthy did take to writing, published his first novel, Jocelyn, in 1899, Villa Rubein in 1900, A Man of Devon and Other Stories in 1901.” Jocelyn has been dropped from the list of Galsworthy’s works, Villa Rubein was revised in 1909, The Island Pharisees, a satire of English weaknesses which appeared in 1904, was revised four years later; and it was not until the publication of The Man of Property in 1906 that our author succeeded in sitting on the Public’s head and twining his fingers firmly into the Public’s whiskers.

This was the first volume of the then-unplanned Forsyte Saga and it led Conrad, who had two years previously dedicated to Galsworthy what remains his greatest novel (Nostromo), to write an article in which he said:

“The foundation of Mr. Galsworthy’s talent, it seems to me, lies in a remarkable power of ironic insight combined with an extremely keen and faithful eye for all the phenomena on the surface of the life he observes. These are the purveyors of his imagination, whose servant is a style clear, direct, sane, illumined by a perfectly unaffected sincerity. It is the style of a man whose sympathy with mankind is too genuine to allow him the smallest gratification of his vanity at the cost of his fellow-creatures ... sufficiently pointed to carry deep his remorseless irony and grave enough to be the dignified vehicle of his profound compassion. Its sustained harmony is never interrupted by those bursts of cymbals and fifes which some deaf people acclaim for brilliance. Before all it is a style well under control, and therefore it never betrays this tender and ironic writer into an odious cynicism of laughter and tears.

“From laboriously collected information, I am led to believe that most people read novels for amusement. This is as it should be. But whatever be their motives, I entertain towards all novel-readers the feelings of warm and respectful affection. I would not try to deceive them for worlds. Never! This being understood, I go on to declare, in the peace of my heart and the serenity of my conscience, that if they want amusement they shall find it between the covers of this book. They shall find plenty of it in this episode in the history of the Forsytes, where the reconciliation of a father and son, the dramatic and poignant comedy of Soames Forsyte’s marital relations, and the tragedy of Bosinney’s failure are exposed to our gaze with the remorseless yet sympathetic irony of Mr. Galsworthy’s art, in the light of the unquenchable fire burning on the altar of property. They shall find amusement, and perhaps also something more lasting—if they care for it. I say this with all the reserves and qualifications which strict truth requires around every statement of opinion. Mr. Galsworthy will never be found futile by anyone, and never uninteresting by the most exacting.”

Twelve years after the appearance of The Man of Property, in the volume Five Tales (1918), was included a long short story, Indian Summer of a Forsyte. The year 1920 saw publication of the novel, In Chancery, and another long short story, Awakening; and the following year brought the novel, To Let. These five units, separately in the order named or together in the same chronological order in the thick volume called The Forsyte Saga, compose a record of three generations of an English family which has very justly been compared to the Esmonds of Thackeray. The Forsytes and their associates and connections are indeed “intensely real as individuals—real in the way that the Esmonds were real; symbolic in their traits, of a section of English society, and reflecting in their lives the changing moods of England in these years.” The motif is clearly expressed by certain words of young Jolyon Forsyte in The Man of Property:

“‘A Forsyte is not an uncommon animal. There are hundreds among the members of this club. Hundreds out there in the streets; you meet them wherever you go!... We are, of course, all of us slaves of property, and I admit that it’s a question of degree, but what I call a “Forsyte” is a man who is decidedly more than less a slave of property. He knows a good thing, he knows a safe thing, and his grip on property—it doesn’t matter whether it be wives, houses, money, or reputation—is his hallmark.... “Property and quality of a Forsyte. This little animal, disturbed by the ridicule of his own sort, is unaffected in his motions by the laughter of strange creatures (you or I). Hereditarily disposed to myopia, he recognises only the persons and habitats of his own species, amongst which he passes an existence of competitive tranquillity”.... They are half England, and the better half, too, the safe half, the three-per-cent half, the half that counts. It’s their wealth and security that makes everything possible; makes your art possible, makes literature, science, even religion, possible. Without Forsytes, who believe in none of these things, but turn them all to use, where should we be?’”

One of Galsworthy’s severest critics, St. John Ervine, calls The Forsyte Saga “his best work,” and breaks the force of many strictures to declare: “The craftsmanship of To Let is superb—this novel is, perhaps, the most technically-correct book of our time—but its human value is even greater than its craftsmanship. In a very vivid fashion, Mr. Galsworthy shows the passing of a tradition and an age. He leaves Soames Forsyte in lonely age, but he does not leave him entirely without sympathy; for this muddleheaded man, unable to win or to keep affection on any but commercial terms, contrives in the end to win the pity and almost the love of the reader who has followed his varying fortunes through their stupid career. The frustrate love of Fleur and Jon is certainly one of the tenderest things in modern fiction.”

iv

Grove Lodge, The Grove, Hampstead, London, N. W. 3, is the residence of Mr. and Mrs. Galsworthy; if you have occasion to telephone, call Hampstead 3684. The approach to the house is described by Carlton Miles in the Theatre Magazine (December, 1922):

“The Galsworthys live at the bottom of a long, rambling lane called The Grove, in that part of Hampstead that looks calmly down on the crowded chimneypots of northwestern London. To reach the house you must climb a steep hill from the underground station and pass the stone building in which Du Maurier wrote Peter Ibbetson and to whose memory it bears a tablet. A few minutes’ walk in one direction and you are in Church Row with the historic cemetery in which Du Maurier and Beerbohm Tree rest side by side. Follow the Grove walk and you arrive on Hampstead Heath, black with thousands of workers on Bank Holiday, overlooking the little row of cottages where Leigh Hunt and his followers established their ‘Vale of Health.’ But, having passed the Du Maurier home, you turn fairly to your left, descend a winding pathway that takes you by the Admiral’s House—designated by large signs—erected 159 years ago by an aged commander who built his home in three decks and mounted it with guns. The guns have vanished but the Admiral’s House still is one of the sights of Hampstead.

“At the end of the lane a small grilled iron gate shuts off the world from a green yard and a low white house, whose rambling line suggests many passageways and sets of rooms. A sheltered, secluded spot, the place above all others where Galsworthy should live. Peace has been achieved in five minutes’ walk from the noisy station. ‘The Inn of Tranquillity.’

“A turn down a long hallway, up a short flight of steps—a bright, flower-decked livingroom, a tea table, a dark-eyed, low-voiced hostess, a clasping of hand by host and a bark you interpret as cautious approval from Mark, the sheepdog, lying on the hearth rug. Mark is named for one of Galsworthy’s characters”—Mark Lennan in The Dark Flower?— “... moments flee before you dare steal a look at the middle-aged gentleman sitting quietly in his chair, striving with gentle dignity to place you at the ease he feels not himself.

“Tall, grey-haired he looks astonishingly like his photographs. Reticent to a degree about his own work, he talks freely and with the utmost generosity about that of others. Opinion, formed slowly, is determined. The face, with its faint smile, looks neither disheartened nor sad, yet sometime it has met suffering. Like most Englishmen the eagerness of youth has not been crushed.... There is nothing chill about the novelist. He is the embodiment of easy, gracious courtesy. Conversation is far from intimidating, a long flow of material topics with now and then an upward leap of thought. And it is this swift flight that betrays his mental withdrawal. As clearly as if physically present may be seen the robed figure of his thoughts, standing behind him in his own drawingroom. You wonder what may be their burden. About him is the veil of remoteness.”

His humility, adorned by his presence and made disarming by what is certainly the most beautiful head and face among the living sons of men, does not always save him from the charge of coldness when manifested impersonally and at a distance. Where nearly all men and women give essential particulars of their lives, not to mention the human touch of their preferred recreations, Mr. Galsworthy, in the English Who’s Who, besides the long list of his publications, states only the year of his birth, his residence, and his membership in the Athenæum Club. This would hardly support Mr. Ervine’s declaration that the Galsworthy sensitiveness “is almost totally impersonal”; and instead of being “startled to discover how destitute of egotism Mr. Galsworthy seems to be” the close student of mankind might be led to speculate upon the variety of egotism he had just encountered. “It may even be argued,” pursues Mr. Ervine, cautiously, “that his lack of interest in himself is a sign of inadequate artistry, that it is impossible for a man of supreme quality to be so utterly unconcerned about himself as Mr. Galsworthy is.” With due respect to Mr. Ervine, this is nonsense. Whatever Mr. Galsworthy may lack, it is not interest in himself. He has achieved countless satisfactory channels for the extrusion of that interest through other and imaginary men, women and beasts—that is all.

v

It is as if he had long ago said to himself, as perhaps he did: “I am myself, but myself isn’t a subject I can decently be concerned about or expose an interest in. Let me forget myself in someone—in everyone—else!” And since then, if he has ever repented, the spectacle of George Bernard Shaw, and particularly the horridly fascinating spectacle of Herbert George Wells, have been before him, to serve as awful warnings and lasting deterrents. Mr. Wells, in ever-new contortions, like a circus acrobat whose nakedness was gaudily accentuated by spangles, began seeing it through with Ann Veronica and is still exposing the secret places of his heart, while dizzy recollections of marriage, God and tono-bungay yet linger. Mr. Shaw has gone back to ... evolution.

“I was,” Mr. Galsworthy has said in an uninhibited moment, “for many years devoted to the sports of shooting and racing. I gave up shooting because it got on my nerves. I still ride; and I would go to a race-meeting any day if it were not for the din, for I am still under the impression that there is nothing alive quite so beautiful as a thoroughbred horse.” His devotion to dogs and other dumb animals is frequently spoken of as it extrudes in Memories, Noel’s protection of the rabbit in Saint’s Progress and “For Love of Beasts” in A Sheaf. These shifting loyalties were—what were they if not admirable realisations of the Self? But let those who still believe Mr. Galsworthy selfless but read the prefaces to the new and very handsome Manaton Edition of his works. For these volumes he has provided sixteen entirely new prefaces. I quote from the announcement of the edition:

“These”—prefaces—“are peculiarly interesting, for in them he frankly criticises his work; in some cases, too, they reflect the response of readers as he has sensed it. In others he tells of the thought in his mind while writing, and of the changes through which the thought has gone in the process. Again, he speculates on the art of writing in general, on the forms of fiction, on emotional expression and effect in the drama. In short, as he phrases it, ‘in writing a preface, one goes into the confessional.’

“Of The Country House he says: ‘When once Pendyce had taken the bit between his teeth, the book ran away with me, and was more swiftly finished than any of my novels, being written in seven months.’

“‘The germ of The Patrician,’ he begins the preface to that volume, ‘is traceable to a certain dinner party at the House of Commons in 1908 and the face of a young politician on the other side of the table.’

“In the preface to Fraternity he says: ‘A novelist, however observant of type and sensitive to the shades of character, does little but describe and dissect himself.... In dissecting Hilary, for instance, in this novel, his creator feels the knife going sharply into his own flesh, just as he could feel it when dissecting Soames Forsyte or Horace Pendyce.’”

The italics are my own and I think they are permissible.

Probably not enough attention has hitherto been paid to Mr. Galsworthy as a writer of short tales, but that may be because no collection of his stories has shown his talent so roundly as does the new book Captures. This opens with the well-known story “A Feud” and offers also such variety and such virtuosity in the short story form as “The Man Who Kept His Form,” “A Hedonist,” “Timber,” “Santa Lucia,” “Blackmail,” “Stroke of Lightning,” “The Broken Boot,” “Virtue,” “Conscience,” “Salta Pro Nobis,” “Heat,” “Philanthropy,” “A Long Ago Affair,” “Acmé,” “Late—299.” In this book, as in similar collections, there must be put to Mr. Galsworthy’s credit his frequent practice of the Continental notion of the short story—the sketch, the impression, the representation of a mood which we find in French and Russian literature and which the American short story too often sacrifices for purely mechanical effects.

Books by John Galsworthy

1900 Villa Rubein. Revised Edition, 1909

1904 The Island Pharisees. Revised Edition,

1908

1906 The Man of Property

1907 The Country House

1908 A Commentary

1909 Fraternity

1909 Strife. Drama in Three Acts

1909 The Silver Box. Comedy in Three Acts

1909 Joy. Play on the Letter “I” in Three Acts

1909 Plays. First Series. Containing The Silver

Box, Joy, and Strife.

1910 Justice. Tragedy in Four Acts

1910 A Motley

1911 The Little Dream. Allegory in six Scenes

1911 The Patrician

1912 The Inn of Tranquillity. Studies and Essays

1912 Moods, Songs, and Doggerels

1912 Memories. Illustrated by Maud Earl

1912 The Eldest Son. Domestic Drama in Three

Acts

1912 The Pigeon. Fantasy in Three Acts

1913 Plays. Second Series. Containing The

Eldest Son, The Little Dream, Justice

1913 The Dark Flower

1913 The Fugitive. Play in Four Acts

1914 The Mob. Play in Four Acts

1914 Plays. Third Series. Containing The Fugitive,

The Pigeon, The Mob

1915 The Little Man and Other Satires

1915 A Bit o’ Love. Play in Three Acts

1915 The Freelands

1916 A Sheaf

1917 Beyond

1918 Five Tales

1919 Another Sheaf

1919 Saint’s Progress

1919 Addresses in America 1919

1920 Tatterdemalion

1920 In Chancery

1920 Awakening

1920 The Skin Game. A Tragi-comedy

1920 The Foundations. An Extravagant Play

1920 Plays. Fourth Series. Containing A Bit o’

Love, The Foundations, The Skin Game

1921 To Let

1921 Six Short Plays. Containing The First and

the Last, The Little Man, Hall-marked,

Defeat, The Sun, and Punch and Go

1922 The Forsyte Saga

1922 A Family Man

1922 Loyalties

1923 Windows. Comedy in Three Acts

1923 Plays. Fifth Series. Containing Loyalties,

Windows, A Family Man

1923 The Burning Spear [first published anonymously

in England in 1918]

1923 Captures

Sources on John Galsworthy

John Galsworthy: A Sketch of His Life and Works. Booklet published by Mr. Galsworthy’s publishers, CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS, 1922.

John Galsworthy. Booklet published by Mr. Galsworthy’s English publisher, WILLIAM HEINEMANN, 1922. Valuable for its bibliography of the English editions.

J. G. Pamphlet announcing the Manaton Edition of John Galsworthy’s works. Procurable from CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS. This edition contains some hitherto unpublished material and a rearrangement of the plays.

The Prefaces to the Manaton Edition. Practically the only discussion of his own work by the author.

Some Modern Novelists. Helen Thomas Follett and Wilson Follett. HENRY HOLT & CO. Chapter X. contains a long and careful critical consideration of Galsworthy’s work up to and including The Freelands.

Some Impressions of My Elders. St. John G. Ervine. THE MACMILLAN COMPANY. For a forceful statement from one of those who strongly criticise Mr. Galsworthy’s work, especially for its “indiscriminating pity.” Analyses at length the play, The Fugitive.

John Galsworthy. Carlton Miles, THE THEATRE MAGAZINE, December, 1922. An interview.

A Middle-Class Family. Joseph Conrad. THE OUTLOOK (London), March 31, 1906. A review of The Man of Property.

The interested reader should further consult the READER’S GUIDE TO PERIODICAL LITERATURE for the years since 1906.

A complete Galsworthy bibliography, to be published in England, is now in preparation by Harold A. Marrot.

2. The Magic Carpet

i

THE Magic Carpet was one which took you far away, whisked you up and through the air (though not sensibly too fast) and brought you into a foreign but delightful country. There are books like that, taking you out of yourself, so that the preoccupation of a moment before is forgotten, tomorrow’s worries are lost, and you exist in a blissful unconsciousness that there can be anything beyond the fine pleasure of this present hour. The “travel book” attempts directly the transfer to some place else; the book of essays, more indirect in its method, is often more successful.

Aldous Huxley has been known to us hitherto as a poet and a writer of fiction. Both his poetry and his fiction have been marked with a graceful artifice and that simplicity which comes only from a completed sophistication. His new book, a collection of essays, is distinguished by those qualities. There is something about Huxley’s writing—I don’t know what it is and those who know what it is, can’t tell—which brings a gleam to the eyes of all who love literature for its own sake. In On the Margin Huxley the satirist walks comfortably with Huxley the student. For Aldous Huxley is a very studious young man. Tall, with hair that bushes out from under his broad-brimmed soft hat, he walks with that slight stoop inevitably acquired by those whose heads do not pass readily under all doorways. With his clothes flapping gently around him, his glance peering through thick-lensed spectacles, he advances into a room with the surprising effect of an amiable scarecrow. A first grotesque impression is rapidly dissolved in the gentle acquaintance springing up immediately afterward; for no more likeable person lives. It is not generally known that between the ages of seventeen and nineteen it was thought he would go blind, so that he learned to read Braille type. His interest in America is keen; he would like to come here, and may. Intimates know him as one of the most learned men in England, though devoid of poses and devoted to finding pleasure in the works of Charles Dickens. His scholarliness shows itself in On the Margin, where Chaucer, Ben Jonson, and the devilish biographer, Mr. Strachey, divide attention with the question of love as practised in France and England, the justice of Margot Asquith’s strictures on modern feminine beauty, and the evolution of ennui.

Recently there died in his ninety-second year Frederic Harrison, who had witnessed the coronation of Victoria in 1838 and every celebration in her reign; who saw her funeral in 1901; who, though past eighty when it began, saw the war of 1914-1918 and the several years of turmoil afterward. An extraordinary life! Before it had ended this man whose span of years was matched by his breadth of knowledge and interests gathered together what he himself regarded as his last book, now published under the title De Senectute and blending some of his finest literary criticism with delightful recollections of the great times in which he lived. A personal account of Victoria and Prince Albert, the “Dialogue on Old Age” which affords the title for the volume, a review of the picturesque history of Constantinople through sixteen centuries, fundamental differences between Greek and Elizabethan tragedy, the art of translation with reference to Dante and Molière, some consideration of Fielding and Smollett and Kingsley, and a final chapter upon various schools of philosophy—these are the relics of a glorious life. The book is full of brightness, its effects are sane, and the writing is alike lucid and tinctured with that peculiar zest which, as it was a quality of Frederic Harrison’s temperament, goes far to explain the length of his life as well as the grace with which he lived it.

Among essayists there are ladies. But there are not many ladies, nor men, either, who have taken rank in the essay with a single book. I understand that Katharine Fullerton Gerould would rather prefer to be known for her fiction—those short stories, masterly in form, with which she began and such a work as her most recent, the brief novel, Conquistador. And such a preference is easily understood. Conquistador, a jewel with many facets, would seduce any woman. And yet Mrs. Gerould’s collection of essays, Modes and Morals, published in 1920, had an extraordinary sale for a book of its character, and still steadily sells. People constantly refer to her discussion of “The Remarkable Rightness of Rudyard Kipling” and the arts of persuasion are constantly brought to bear upon her to assemble another such book. If Mrs. Gerould began with something of the suddenness of a meteor, she persists with a good deal of the steady brilliance of a fixed star. It was, in fact, with the appearance of a story, “Vain Oblations,” in Scribner’s Magazine for March, 1911, that she first came to general notice. This dark and terrible piece of fictional analysis had for its principal character a New England woman missionary. Other stories followed in Scribner’s, the Atlantic and Harper’s, and a first collection, under the title Vain Oblations, was published in March, 1914. A second book of tales, The Great Tradition, was succeeded by a novelette, A Change of Air; by the essays comprising Modes and Morals; and then by the novel, Lost Valley. Valiant Dust offered some more short tales; but with the appearance of Conquistador many of us felt Mrs. Gerould for the first time to be perfectly suited in length, form and material alike. Despite her superb technique, she needs more room than the short story gives her; and although she can write of barren New England lives she can write much more effectively of richly-coloured Latin life. Although, as Stuart P. Sherman has observed, she can do dashingly the “picture of a really nice woman meditating a fracture of the seventh commandment in a spacious sun-flooded chamber with a Chinese rug,” her deep fictional desires are toward the richly barbaric, and neither Henry-Jamesical nor Edith-Whartonesque. In the atmosphere of Princeton, which is her home (her husband, Gordon Hall Gerould, is a member of the English faculty), she has the leisure and repose necessary to do such essays and short novels as no other living American has given evidence of an equal talent for achieving. Occasionally a bit of travel, perhaps, producing as its direct result a book like her Hawaii, Scenes and Impressions; but ultimately much more valuable for its indirect stimulus to her imagination, which belongs to the class of imaginations so dangerous when they are confined.

In fact, the imagination is very little understood, as if it were one of those glands whose mysterious secretions we tinker with nowadays, either not too successfully or with a success so alarming as to threaten the overthrow of all physiology. One of these days we shall have a mental thyroid extract, and then—! It remains to be observed that with most of us the imagination secretes gently, with a fresh annual activation in the direction of old woods and pastures ever-new, rather than new; a circumstance very favourable to David Grayson when, in 1907, he put forth the volume called Adventures in Contentment. It is difficult to think of any precise precedent for this mixture of essay, philosophy, homely observation and quiet humour with its essentially American pattern of thought. The febrile character of much American life was already marked, and the remedy of an equally feverish optimism had yet to be widely prescribed. The time was propitious, the sentiment of David Grayson had an ingratiation. When, in 1910, Adventures in Friendship was published, a good many thousand people had read the earlier adventures and were alert for these. The Friendly Road (1913) was succeeded by Hempfield (1915) and a final volume, Great Possessions (1917). A half dozen years have passed without relegating these books to the shelves of the Great Unread. As “The Library of the Open Road” they inherit an annual, rather a perennial, popularity.

ii

In the course of reading a great number of travel books, I have come to prefer my Baedekers to all others. The worthy Karl’s “handbooks for travellers” are not only the standard guides (and likely to remain so) but they seem to me perfect in their exactitude, their literalness and their discreet prescriptions for the visitor’s emotions. If I wish to know the number of yards to walk from the castle gate and the right entrance through which to pass to emerge upon a View, I wish also to know in a general way how to graduate my feelings on beholding the spectacle spread out at my feet. And this, Baedeker tells me. By the unstarred, starred or double-starred nature of his reference to the View, I know with reassurance whether my emotional response should be elementary, intermediate or advanced. Moreover, there is lacking no concrete detail from which the fancy may launch itself. To read Baedeker is to use one’s own wings, and not somebody else’s. This is a great virtue; for in book travels, as perhaps in other travel, it is much more desirable to make one’s own appraisal than to accept another’s description of the beauties of a place. And I really have known a novelist to reject every particular travel book dealing with a certain town or region in which his scene was laid, because he felt hampered by their emotionality and their impressionism and a quality of vagueness, and turn with joy and relief to his Baedeker’s Mediterranean or Northern Italy or Spain and Portugal. Here the matters essential to accuracy were given—and only a novelist who has heard the protest of literal-minded readers can know the penalties of a topographical mistake—but the perfectly-set stage stood cleared for the actors of his writer’s imagination. For the benefit of those attending the assemblies of the League of Nations, one of the most freshly revised volumes is Baedeker’s Switzerland; another of equal recency is the guide to Canada.

In spite of the twenty-seven books of the Baedeker series, there is a good deal of the world which is not even touched upon in these famous guides, which are, after all and with slight exception, properties for the tourist in Europe and the Mediterranean countries. The tourist, however, more and more declines to stick to Europe, a large number of him having seen Europe pretty thoroughly anyway. As for the tourist in fancy, he goes everywhere. The business man is another traveller who is omni-itinerant. I suppose the widest audience for the series of books called “Carpenter’s World Travels” is composed of what one commentator rightly describes as “the incalculable company of stay-at-home travellers.” Frank G. Carpenter himself is the best guarantee that the matter and form of the planned twenty-five volumes will remain as excellent as in the seven already brought out. For over thirty years this highly skilled journalist has walked the earth, even to the ends of the earth, and written of what he saw. Some four million copies of his Geographic Readers have sold to the public schools, and an equal number of families now open their newspapers once a week to find his new series of letters from the countries of Europe. In fact, Mr. Carpenter is a publicist of so vast and important an audience that Governments have been glad to give him access to every official source of information, and various rulers and prime ministers have at one and another time especially commissioned him in facilitation of his work. The many and exceptional photographs in his hands have made it possible to plan the use of about one hundred of the best in each volume of the series now under way. Java and the East Indies and France to Scandinavia (France, Belgium, Holland, Denmark, Norway and Sweden) are his latest additions to the beginning made with The Holy Land and Syria. From Tangier to Tripoli (Morocco, Algeria, Tunis and the Sahara), Alaska, Our Northern Wonderland, The Tail of the Hemisphere (Chile and Argentina) and Cairo to Kisumu (Egypt, the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, and British East Africa) were the intermediate books.

“Adopted as a motto this year, ‘The world is my parish,’” wrote down Stephen Graham, at the end of his travel record for 1921—a record that begins with that first pilgrimage of his to Russia in 1906. Even so, he finds parts of his parish yet unvisited, and the next year saw him off on fresh Latin trails. It had come over him, indeed, to traverse some 15,000 miles that represent one of the most fabulous of mankind’s adventures. Graham had a thought to approach our present America in the path of those first explorers and in the spirit of the conquistadores, following Columbus from Spain to the Indies, Balboa to the peak in Darien whence he saw the Pacific, Cortes to the conquest of Montezuma’s capital, and Coronado on the fruitless quest into the deserts of New Mexico and Arizona. What happened? Why, in the words of Vachel Lindsay, Graham’s tramp companion in the Rockies:

and Graham, whose intimacy with Russian life and thought has deeply enriched a natural mystical endowment, found a significant theme in the Spanish quest for gold succeeded, after four centuries, by the American quest of power—religion the sanctification of one, pan-Americanism the credo of the other. It is this spiritual penetration that makes the fine distinction of Stephen Graham’s In Quest of El Dorado, joined to the man’s unusual literary skill, taste and sense of form. On the point of form there is something more than usually admirable in the start of the book from Madrid and Cadiz and in the conclusion (on a note of wonder) amid the ruins of Mitla, as if the quester for El Dorado would do well to seek its whereabouts in the indecipherable inscriptions placed on their massive memorials by a race that had sunk into silence long before the imperious advent of the Children of the Sun. These are the refinements of the book for the reader of philosophical or æsthetic tastes; but as such matters should be, they are entirely unobtrusive—present to those who seek them, hidden to those who are indifferent—and in externals Stephen Graham offers a first-hand travel study with cowboys and conquistadores, Indians and Mexicans, the Panama Canal and the jingle of spurs in the changing foreground.

Among those authors whose books of travel win their appreciation from the personality of the adventurer, Mary Roberts Rinehart seems to me quite plainly the foremost. The considerable time that has elapsed since the publication of Through Glacier Park and Tenting Tonight will sharpen many appetites for the camp fare offered in her new book, The Out Trail. With none of the acerbity of her own Tish, Mrs. Rinehart has to the full that lady’s derring-do. “I have roughed it,” she explains at the beginning of The Out Trail, “in one wilderness after another, in camp and on the trail, in the air and on water, in war abroad and in peace at home. I have been scared to death more times than I can remember. Led,” she confesses, “by the exigencies of my profession, by feminine curiosity, or by the determination not to be left at home, I have been shaken, thrown, bitten, sunburned, rained on, shot at, stone-bruised, frozen, broiled, and scared, with monotonous regularity.” And she adds that on several occasions she has been placed in situations of real danger from which she has clamoured to be extricated with all possible despatch. Two things, if we may judge by her chronicle, seem never to have failed her, in whatever emergency: her sense of drama and her sense of humour. At least, they are keenly in evidence on all the pages of The Out Trail, and make it easily among the most entertaining books of its kind—not infrequently exciting, too! If someone thinks that the sense of the humorous must have been missing at the time and have been recaptured later in writing of the adventures, I suspect he is mistaken; for I recall that not so long after I had written a chapter on “The Vitality of Mary Roberts Rinehart” as a novelist, I met Mrs. Rinehart. She was suffering from one of those ferocious colds which make cowards and pessimists of us all, but she only remarked: “I’m afraid you will find the vitality you have just celebrated rather low this morning.” This, I submit, is such stuff as humorists are made on.

iii

Among books of essays that successfully spread the Magic Carpet for readers I should like to draw attention to the following (in addition to those described above):

ROBERT CORTES HOLLIDAY’S In the Neighborhood

of Murray Hill.

J. C. SQUIRE’S Essays at Large and his Books

Reviewed.

HILAIRE BELLOC’S On.

Other collections of essays, chiefly on literary and philosophical subjects, are included in or listed after Chapter 15, “For the Literary Investor.”

iv

In the matter of books of travel, some classification is necessary, and in addition to the ones just described I am glad to name the following in all their happy variety:

A Group of Books on Ancient Egypt and

Present-day Egyptian Explorations.

A History of Egypt From the Earliest Times to the Conquest of the Persians, by JAMES HENRY BREASTED. The ninth printing has just been called for. With 200 illustrations and maps.

History of Assyria, by A. T. OLMSTEAD. A companion volume to Breasted’s History of Egypt, and equally admirable. With maps and many illustrations.

G. MASPERO’S Life in Ancient Egypt and Assyria, his Egyptian Art: Studies, and his History of Art in Egypt. These remain standard in their field.

TERENCE GRAY’S And in the Tomb Were Found and his The Life of Hatshepsut. The first is a series of historical studies and sketches including Khufu, builder of the Great Pyramid, and Rameses the Great. Some literal translations of Egyptian love songs are added. The second book is the romance of an Egyptian princess who reigns as a man; the work is cast in the form of a pageant for the sake of greater vividness.

PERCY E. MARTIN’S Egypt Old and New, a general account with many illustrations in colour.

PERCY EDWARD NEWBERRY’S The Valley of the Kings, which includes the discoveries by the late Lord Carnarvon and Howard Carter in a general account of thirty years’ explorations.

ARTHUR WEIGALL’S Tut-Ankh-Amen and Other Essays is the work of an Egyptologist and former Inspector-General of Antiquities in Egypt. Mr. Weigall was special correspondent for the London Daily Mail, New York World and other newspapers at the opening of the tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amen.

A Group of Books About China.

Audacious Angles on China, by ELSIE MCCORMICK, introduces the reader to Chinese life as the Western resident there sees it. The humorous side of such experiences is to the fore, and one part of the book is devoted to “The Unexpurgated Diary of a Shanghai Baby”—an American child’s view of the intimacies of Eastern life.

Swinging Lanterns, by ELIZABETH CRUMP ENDERS, is a vivid narrative of what an American woman saw while living and travelling in China. It contains much that is unusual, including such matters as the Yellow Llama Devil Dances, never before described. Fine illustrations.

ROY CHAPMAN ANDREWS’S Across Mongolian Plains.

ROY CHAPMAN ANDREWS’S and YVETTE BORUP ANDREWS’S Camps and Trails in China.

HERBERT A. GILES’S A History of Chinese Literature, a historical account written with much charm and taste and offering translations of the work of various Chinese writers.

The Far East.

C. M. VAN TYNE’S India in Ferment. Mahatma Gandhi and the general background by a scholar and skilled observer.

SIR HUGH CLIFFORD’S A Prince of Malaya and his earlier book, The Further Side of Silence. These are stories, true, fictional and semi-fictional, that take rank as literature. The author, a friend of Joseph Conrad, at the age of twenty-one was “the principal instrument in adding 15,000 square miles to the British dependencies in the East.”

SYDNEY A. CLOMAN’S Myself and a Few Moros. An American soldier’s lively but not unhumorous administrative experiences, with a good picture of what the United States has accomplished in colonial government.

H. O. MORGENTHALER’S Matahari. The Frederick O’Brienish adventures of a Swiss engineer prospecting for tin in the Malayan-Siamese jungle.

The Callers of the Wild.

ERNEST THOMPSON SETON’S Game Animals and the Lives They Live, Vol. I. There are to be four volumes.

WILLIAM T. HORNADAY’S The Minds and Manners of Wild Animals, a book of personal observations by one of the keenest living observers and one who, as director of the New York Zoological Park, has under his eye and care the most complete collection in the world.

SAMUEL A. DERIEUX’S Animal Personalities, including domesticated animals.

CARL AKELEY’S Men and Animals: An Autobiography and MARY HASTINGS BRADLEY’S On the Gorilla Trail. Mr. Akeley went to the Belgian Congo on a gorilla expedition, and Mrs. Bradley, well-known as a novelist, her husband and their five-year-old daughter went, too. Each book enhances the interest of the other.

With Ice.

APSLEY CHERRY-GARRARD’S The Worst Journey in the World, describing, in its two volumes, Scott’s last Antarctic expedition, 1910-13.

Mediterranean.

V. C. SCOTT O’CONNOR’S A Vision of Morocco, which is both historical and descriptive, and C. E. ANDREWS’S Old Morocco and the Forbidden Atlas, written in a distinguished prose.

C. R. ASHBEE’S A Palestine Notebook, the result of administrative experience in 1918-22. The book has interesting personal portraits of Sir Herbert Samuels, General Allenby, Lord Robert Cecil, Lord Morley, the late Lord Northcliffe, Lord Curzon, and others.

G. K. CHESTERTON’S The New Jerusalem.

ERNEST PEIXOTTO’S Through Spain and Portugal, where the author’s illustrations are so happily wedded to the text.

ROSITA FORBES’S The Secret of the Sahara: Kufara.

South America.

C. REGINALD ENOCK’S Republics of Central and South America, his Spanish America (two volumes), his Ecuador, his Peru, and his Mexico.

LEO E. MILLER’S In the Wilds of South America, an account of six years’ explorations.

Unique Books of Travel.

GEORGE EYRE-TODD’S The Clans of the Scottish Highlands. By an authority on Scots lore.

VAUGHAN CORNISH’S A Geography of the Great Capitals, from the “capital” of the Iroquois Indians, marked by a sacred fire, to the capitals of government, such as Rome and London, or of commerce, such as New York, and including vanished cities as well as existing ones.

THOMAS NELSON PAGE’S Washington and Its Romance, really a historical work. Mr. Page had been engaged upon it for several years before his death and left completed his account of the city’s early days.

S. R. ROGET’S Travel in the Two Last Centuries of Three Generations, a remarkable history, vivid, personal and interesting, derived from the records and letters of a single family and showing what rapid changes transportation underwent in the short period of two hundred years.

B. W. MATZ’S Dickensian Inns and Taverns, and his The Inns and Taverns of Pickwick, and also CECIL ALDRIN’S magnificent Old Inns—for all who hear the post horns blow and the stage coach drive up to the door.

STEPHEN GRAHAM’S Tramping With a Poet in the Rockies, the description of a vagabondage with Vachel Lindsay, with a report of many conversations which left the ground.

3. A Breathless Chapter

i

WHAT actually took my breath away (in the first place) was an inspection of the “general catalogue” of one of our publishing houses, and a discovery therein. Now, a general catalogue, showing all the books published by a particular house and “in print”—that is, procurable new—is in itself a species of adventure. I admit all that Mr. A. Edward Newton puts forward as to the amenities of book collecting—by which, I take it, he means the joys, the sorrows, the moments of irony and the moments of amusement which fall to the lot of the collector of rare books. The quest of the book that is out of print, and must be had at second hand by diligent search and patient waiting, is an exceptional delight. Nevertheless, a special and more accessible pleasure lies in the catalogue, whether of a publisher or a bookshop. All but a handful of us are certain to come upon titles that kindle the imagination or rekindle the memory. Both were lit for me by the entry:

Gaboriau, Emile

The Most Complete Library Edition

Each with new illustrated jackets

The Count’s Millions. 12mo. 2.00

And not only The Count’s Millions, but a roll of eleven others, an even dozen in all, ready to be re-read after these too many years and pleasingly freshened up by the new illustrated jackets! There they were: Baron Trigault’s Vengeance, The Clique of Gold, and a fine array of enticing titles that memory doesn’t recall—The Champdoce Mystery, Within an Inch of His Life, which has the proper ring; The Widow Lerouge; Other People’s Money, always an engrossing subject; The Mystery of Orcival (illustrated by Jules Guerin) and one or two others besides (of course!) Monsieur Lecoq and that famous File No. 113. It is desolating to reflect that there must be thousands, perhaps millions, to whom the name of Monsieur Lecoq conveys nothing and who are totally unacquainted with File No. 113, the most marvellous genealogical mystery story ever written, a tale in which one does not know which more to admire, the genealogy or the plot, until one grasps that the genealogy is the plot, and that what is desperately needed is not a detective but an expert in the ascension of family trees. However, that is not the worst. A yet more fearful thought concerns the author himself. It is even possible that there exists a whole generation, and perhaps races of men, to whom the name of Gaboriau is nothing but part of a quatrain (though rather a famous jingle) perpetrated first by Julian Street and James Montgomery Flagg under the auspices (I think) of Franklin P. Adams (“F. P. A.”):

Too, too flippant! Recalling Monsieur Lecoq, one exclaims: “There were detectives in those days!” And then again, such despondency is excessive. There is, now and occasionally, a detective in these days also. For proof, look at this fellow, Monsieur Jonquelle, in Melville Davisson Post’s new book of that title. Ah! M. Davisson Post! It is but to mention him to introduce a new and important subject, n’est ce pas?

Mr. Post is worth talking about, certainly; and assuming that you have read him, you have probably discussed what you read afterward. His reputation as a writer of detective-mystery stories was pretty well abroad before the publication of Uncle Abner, Master of Mysteries, but that book established the reputation solidly. My recollection is that even before its appearance Mr. Post had written one or two articles in which he explained his theory and practice of story writing. I may simply remark that he went into the matter with as much technical skill and artistic nicety as Poe or de Maupassant; the man is an artist to his fingertips and his work shows it. One has the feeling of construction and the sense of ornamentation springing from fine tastes; his tales are like beautiful pieces of cabinet work in which, at first sight, the effects of form, of shapeliness and of beauty and power are felt; on a closer examination you fall to admiring the sure hand and the cunning art; and at last your exploring fingers touch a particular joint, disclosing an unsuspected drawer that flies out and reveals the story’s secret ... though not Mr. Post’s secret, which, like that of all genuine artists, remains with himself. If this has a ring of exaggeration to your ear, I need only refer you to such a perfect thing as the opening tale, “The Doomdorf Mystery,” in Uncle Abner. Or you may make the test on Monsieur Jonquelle, where likewise all the stories turn on a central character, the Prefect of Police of Paris. Monsieur Jonquelle exemplifies very well Mr. Post’s method of developing the mystery and its solution side by side. The gain in movement and surprise is the compensation for a technique immensely more difficult than the usual formula, by which a mystery is first built up and then, with inevitable repetition, dispelled. Those who are interested in the mechanism of stories will also find it worth while to consider why Mr. Post varies the narrative standpoint in his new book, so that some of the tales of Monsieur Jonquelle are related by the chief character, some by a third person, some by the author.... Mr. Post is a native of West Virginia, where he lives (Lost Creek, R. F. D. 2). A lawyer by training, he became particularly interested in the possibilities that lie open for the use of the law to aid the commission of crime; and this led to his first book, The Strange Schemes of Randolph Mason, in which this perversion of the law to criminal ends was the tissue of the stories.

A rural free delivery route at Lost Creek, West Virginia, has about it something pleasing in connection with a writer of breathless fiction, but the height of suitability in authors’ residences belongs to Beatrice Grimshaw, whose mystery-adventure yarns of the South Pacific begin to be as numerous as a group of Pacific Islands. Indeed, I feel it would be no surprise some day, running before the southeasterly trade wind in a longitude west of 135 degrees and a latitude exceeding 20 degrees south, to sight a succession of dark blue cloud shapes lying on the horizon and be told: “Yonder’s the Beatrice Islands of the Grimshaw group—big archipelago.” Beatrice Grimshaw lives at Port Moseby, Papua, New Guinea, and is a planter as well as an author. There is practically no place in the South Seas which she has not visited, including the cannibal country of Papua. An old and possibly untrue story recalled by Hector MacQuarrie tells of a time when, on a schooner in mid-Pacific, “the captain, a gentle ancient, thinking that the dark women were having it all their own way, offered to embrace Miss Grimshaw, finding in return a gun pointing at his middle, filling him with quaint surprise that anyone could possibly offer violence in defence of a soul in so delightful a climate.” Anyway, the lady knows her corner of the world and the people in it, as anyone may discover by the exciting enterprise of reading such a book as The Sands of Oro, with its strange group of five persons bound together by necessity and ugly chance, and committed to each other’s fortunes for a term on a lonely Pacific island. Here, as in the author’s Nobody’s Island, the reader is at once let into the general secret with the result of a deepening mystery as to why and how and what next.

In truth, the tale which attempts breathlessness simply by the device of withheld explanations takes our breath away no longer. We have come to demand of the author that he proceed with direct and forward action, producing genuine interest instead of merely artificial suspense. He must hew to the line of his story, must move, letting the explanations, chips of his tough puzzle, fall where they may. Thus it has come about that the mystery story which is not also an adventure story fails to capture our interest or stir our curiosity. Of living writers, one of the earliest to grasp this was A. E. W. Mason. With others, I feared a half dozen years ago that he might have forgotten the vital principle; for his story of The Summons was quite unlike the Mason who had given us The Four Feathers, The Witness for the Defense, and other superb novels. But the fear may be dissipated, for in his new book, The Winding Stair, Mr. Mason has written a story comparable with his best work. Like The Four Feathers, it is a tale of cowardice becoming ultimate bravery; and I do not recall a heroine so pitifully appealing, so desperately lovable, so admirably brave as Marguerite Lambert since Joseph Conrad gave us the girl Lena in Victory. Possibly the title of Mr. Mason’s newest work may, offhand, convey the wrong flavor to the incipient reader; it is not a yarn of mysterious goings-on in some old mansion but the history of a soldier and the son of a soldier, moving principally in Northern Africa; the very appropriate phrase that christens the book is quoted from no less person than Bacon, “All rising to Great Place is by a winding stair.” Seldom does one come upon a novel of adventure which is also so profoundly a novel of character or which has so direct and free an appeal to the emotions, or makes that appeal so successfully. The Winding Stair is the work of a masterly storyteller, and such scenes as those of Paul Ravenel’s discovery of who he is, his rescue of Marguerite Lambert, and Marguerite’s discovery of his self-betrayal sprung from his love for her are something more than exciting drama. There is a breathlessness here that comes from a slowing-down rather than a quickening, from a pause, from a moment of perilous silence in which the only sound or sensation is the painful throbbing of the human heart.

ii

The other way of breathlessness is laughter.

“Laughter, holding both his sides,” sang Milton; and, in fact, I once knew a man who sat at a dinner or some place between Don Marquis and Pelham Grenville (P. G.) Wodehouse. It is not necessary to recall what happened to him. Let us draw a veil, and proceed. Don (perhaps you recall it) was under the necessity of conducting a guessing contest in a New York newspaper. The purpose was to guess his real name. People refused to believe that he could be Don Marquis. The Supreme Court, in a case brought as a test, has since decided that such incredulity is not a sign of moral turpitude. Even Donald Robert Perry Marquis, held the Court (seven to two; Holmes, J., and Brandeis, J., dissenting), does not sound sufficiently possible, especially when the evidence shows that he was born in Walnut, Bureau County, Illinois. The Court ruled that Don was conceivably a literary hoax, but that his play, The Old Soak, was the real thing and within the Amendment. Popular rather than judicial cognisance has extended to the other and uncollected works of Don Marquis, such as Prefaces, his stories in Carter and Other People, his truth-telling about a young woman called Hermione, his newly rededicated record of The Cruise of the Jasper B., his iliad of Noah an’ Jonah an’ Captain John Smith, his poetry in Sonnets to a Red-Haired Lady and Famous Love Affairs, etc., etc. You have read Anatole France’s The Revolt of the Angels, but are you familiar with Don’s The Revolt of the Oyster, I ask you? Or Pandora Lifts the Lid, by Christopher Morley, writing under the auspices of Don Marquis? Or The Almost Perfect State, a vision vouchsafed exclusively to Mr. Marquis?

The truth is, there is a good deal of Mark Twain in Don Marquis. Don is usually as good as ever Mark was and in some cases a good deal superior—and throughout, more genuine. When I make the comparison I am thinking of the best Mark Twain, the satirist and not too easily satisfied thinker; neither the embittered and savage pessimist of those final years nor the facile (too facile) humourist. Marquis, who can sustain the severer comparison with Twain, can also well sustain the comparison on the lighter side; for Don is a humourist, too. The point is in the “too.” And the exemplification may be sought in (let us say) The Almost Perfect State. “No matter how nearly perfect an Almost Perfect State may be, it is not nearly perfect enough unless the individuals who compose it can, somewhere between death and birth, have a perfectly corking time for a few years.... In the Almost Perfect State every person shall have at least ten years before he dies of easy, carefree, happy living.” A place of pay-as-you-enter wars; a heaven where everyone is an aristocrat and there are no professional reformers—in short, a Marquisate. Where Don differs from Mark Twain is in being a poet who sometimes uses poetry as the medium of his expression—see Dreams and Dust and his Poems and Portraits. Christopher Morley (whose essay on Don Marquis, in Shandygaff, deserves to be read) has coaxed Don into a Frank R. Stocktonish enterprise in Pandora Lifts the Lid, with its narrative of seven young women snatched from the shades of a young ladies’ seminary and—. But as I write, Pandora has lifted the lid on a crack only.

P. G. Wodehouse is another matter, a chap over whose books thousands of people have found themselves unable to keep straight faces. Yet, not long ago, writing in the London Sphere, Clement K. Shorter declared he had never read a single one of the more than twenty Wodehouse yarns. He had never read Jeeves, or that new one, Leave It to Psmith, or Mostly Sally, or Three Men and a Maid, or The Little Warrior, or A Damsel in Distress, or Piccadilly Jim—think of it! Or no, don’t think of it. It won’t bear thinking of, it won’t really. The Wodehouse novels, though in most respects like those jolly things he writes to go with music by Jerome Kern, have now and then a page that dips far below the surface of fun into something very deep and true to the inwardness of human nature. Such are some bits in The Little Warrior, and such are the more tragic moments for Sally in Mostly Sally; and yet Mr. Wodehouse brings his story up again quickly like a diver clutching a pearl and rising up through clear water to sparkling and sunlit air. It is the prettiest talent imaginable, and I can think of no other contemporary writer of light fiction who has the same dexterity.

iii

There is no formula for achieving breathlessness. Those who are most susceptible to what may be loosely called Plot will find an enviable difficulty in breathing while they peruse, besides the stories already mentioned, some of the following tales:

JOHN BUCHAN’S Midwinter and his Huntingtower. Buchan is a master of suspense and a humourist of very exceptional quality. His stories are rightly called “the grandest of grand yarns.” Have you ever read Greenmantle? The literary merit of these books (quite incidental) is far above the average of their kind.

FRANK L. PACKARD’S The Four Stragglers, an “unguessable” story with a steady acceleration of excitement, and his new one, The Locked Book.

WILLIAM GARRET’S Friday to Monday, which will give you the liveliest week-end of your possibly rich experience. Black pearls, a Chinaman, torture, a fight in the dark, a rocky cavern of the sea and an airplane are used.

WILLIAM JOHNSTON’S The Waddington Cipher.

H. C. MCNEILE’S The Dinner Club. The six members had each to tell two stories worthy of the dinner, and did! Also H. C. McNeile’s The Black Gang, with its further adventures of Bulldog Drummond.

ALBERT PAYSON TERHUNE’S The Amateur Inn, remarkable not only for its mystery puzzle but for the presence of an irresistible maiden lady who says: “A person not ashamed to lock a door with a key, need not be ashamed to lock his mind with a lie.”

CAROLYN WELL’S Wheels Within Wheels, another story with Penny Wise as the detective. The village idiot is a protagonist.

C. N. and A. M. WILLIAMSON’S The Lady From the Air and their The Night of the Wedding.

When Ghost Meets Ghost.

The “borderland” in F. BRITTEN AUSTEN’S On the Borderland is the region between the conscious and the subconscious, assuming that such a neutral zone exists. The book offers twelve weird stories striking in their ingenuity.

E. F. BENSON’S Spook Stories.

Ordeal by Water.

TRISTRAM TUPPER’S Adventuring is entirely off the beaten track of adventure fiction—the story of a middle-aged, ordinary man whose love for the songs of the Grecian Sappho quickens his imagination to a dream of her beauty and leads him into an homeric sea adventure.

A. HYATT VERRILL’S The Real Story of the Pirate. A fascinating book about those fellows whose colouring is perhaps a little faded in spite of their being scoundrels of the deepest dye; although (as you may not know) Kidd was by no means so black as he was hanged for being.

A. HYATT VERRILL’S The Real Story of the Whaler. More thrills for all of us who had ’em as we watched the film, “Down to the Sea in Ships.”

Almost Anything by HAROLD MACGRATH.

His The World Outside, or, if you haven’t read them:

The Ragged Edge

The Pagan Madonna

The Man With Three Names

The Drums of Jeopardy

iv

Let us approach the subject of humour circumspectly. In addition to the Works of DON MARQUIS, passim, as the reference books say, and the Works of P. G. WODEHOUSE, both before-mentioned, and the Works of DONALD OGDEN STEWART (see Chapter 13, “A Parody Outline of Stewart”), and the Works of IRVIN S. COBB in many places, the reader may be well advised to consult at the outset Tom Masson’s Annual for 1923, a humorous anthology; KATHARINE DAYTON’S Loose Leaves, IRVIN COBB’S collection of the best humorous stories he has ever met, A Laugh a Day Keeps the Doctor Away, and—oh, yes!—the Works of OLIVER HERFORD, including Neither Here Nor There and This Giddy Globe. A word of warning in regard to a couple of others:

FRANCIS B. KEENE’S Lyrics of the Links. This is not a humorous book on days when you are off your game. Still, you can’t afford to miss Grantland Rice’s foreword to the lyrics.

THOMAS L. MASON’S That Silver Lining, although written largely in a humorous vein, is an honest-to-goodness book about new thought, mental healing, psycho-analysis and so forth, by a survivor of twenty-eight years of Life.

4. In the Kingdom of Conrad

i

I ONCE knew such a man,” declared Marlow. I don’t believe any of us felt moved to reply. To have indicated, by a syllable or two, a polite interest, would have been fatal. Marlow, in the presence of anything but an aloof skepticism or a cynical reserve, becomes tiresome in his pursuit of metaphysical abstraction. He seems to think it can be caught in the butterfly-net of words.... Now he sat, sucking his pipe (he always cools it before re-filling) and looking attentively at each of us as the sparks of cigars momentarily threw a faint gleam on our faces. At length:

“You all know him, too,” he pronounced. “Chap named Conrad, Joseph Conrad. Teodor Jozef Konrad Korzeniowski. That Polish sailor; writes novels. But he has a master’s ticket. Got blackwater fever or something down at the Congo; he was out East before that. Then he settled in Kent, in a little house, where I once went to see him. Of course you’ve read Lord Jim; I don’t think a lot of it. Give me Victory or Youth, or, best of all, Nostromo——”

“Personally, Marlow, I always look at the end first, to see how it comes out. Since you are beginning in the middle——”

“I? I’m not, but Conrad was. Did you ever read Nostromo? Talk about beginning a story in the middle!”

“Well, if you want to talk about that,” sighed a voice. “My impression was, Marlow, that you were undertaking to tell us about a man who knew himself—shall we say?—singularly well.”

“Exactly.” Marlow uttered the word with something that might have been reluctance. He repeated it, “Exactly.” It was time to re-fill his pipe and he made a long job of it. When he had it drawing nicely and began to speak again his voice was veiled, his choice of words was frequently made with a certain hesitation, and we listened without comment or any other interruption than the occasional shifting of a foot on the deck. At least, I can recall nothing; and I know we borrowed our matches by signs—when we thought to borrow them.

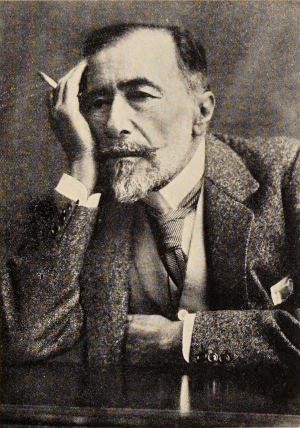

JOSEPH CONRAD

ii

“As you have heard something of him, I won’t waste my breath on the bare biographical record,” Marlow informed us. “I believe you all know he was born in the Ukraine in 1857; sixth of December happened to be the day. His father and mother were Polish patriots and Russian exiles and their death left the boy in the hands of his mother’s brother, who used him affectionately and engaged a very capable tutor to fit the young Korzeniowski for the University of Cracow. It is pertinent, I think, that the father had been a man of scholarly tastes and occupation. He had succeeded in translating Shakespeare into Polish. The legendary figure of a great-uncle, whom, however, the boy had seen, made a great impression. Mr. Nicholas B., as Conrad calls him in his book, A Personal Record, was in the retreat from Moscow and had the strange misfortune to share in eating a Lithuanian dog. Did you ever read Falk? Mr. Nicholas B. transmuted into fiction, I should say. The one had eaten a dog, the other was credited with having eaten human flesh; but the effect is the same. Then there’s that other story, Heart of Darkness—the one all the authorities acclaim as among the half-dozen greatest stories in English. I have heard Conrad narrate the actual incident as it befell him down at the Congo; I have also read, and heard him read aloud, his tale. Very interesting. Let us admit that truth is frequently stranger than fiction; what then? Why truth is so often unintelligible, void of significance, without meaning. Whereas fiction is the real truth—all we can grasp, anyway. How we abuse words! It is facts, or apparent facts, that are stranger than so-called fiction. Not truth! Let us save that word for finer purposes. The conquest of brute facts? Well, maybe.

“This Polish boy I am telling you about had an incomprehensible wish. I understand that nowadays there is no such animal as an incomprehensible wish. All wishes are fulfilled, or something of the sort. The boy’s wish I am speaking of was fulfilled, safe enough, but its comprehensibility is still in doubt. At any rate, he wanted to go to sea. As almost all boys wish urgently to go to sea, this might not appear abnormal. Perhaps, after all the oddity lay chiefly in the attitude of his uncle and tutor, which was strongly adverse; also, to some extent, in the fact that Poland is (or then was) purely an interior country without ships or the enticing sight of sailors to tempt a boy. A country of farmers. And he left it. He has told in A Personal Record of the last stand made by the tutor and his uncle. The sight of an Englishman in the Alps had the mysterious effect of making the lad more set in his purpose than ever. Why, as I say, is not comprehensible, unless by those serious scientists who exist in Vienna and play jokes on the rest of the world.

“When he had got clean away, with a sorrowful blessing, he fared to the Mediterranean. He wanted to become not merely a sailor but a British sailor; he knew no English. French, of course, he knew, as befitted a Pole of a good family and some education. It was not so difficult to get berths on Mediterranean vessels. Being in his teens, he was looking for excitement and adventure. This, too, mare nostrum provides. It does not really matter, I take it, where one sows his wild oats, provided only he sows thickly; and the waters of the Mediterranean received a bushel or two from Poland (a strictly agricultural land). One harvests such a crop from the sea uncertainly and at a long interval, but the sea’s return is often curious and beautiful. Fragments, if you like, but of a loveliness not yielded by the soil of the shore; mother-of-pearl’d, glistening. And out of that uncouth time and those bizarre experiences the man Conrad has got back certain pages in The Mirror of the Sea, pages that we all remember. The Arrow of Gold, also, is the return of those years when he was irregularly employed in smuggling and gun-running out of Marseilles to the loosely-guarded shores of Spain.