Cargoes for Crusoes

Grant M. Overton

Cargoes for Crusoes

GRANT OVERTON

By GRANT OVERTON

About Books and Authors

- CARGOES FOR CRUSOES

- AUTHORS OF THE DAY

- AMERICAN NIGHTS ENTERTAINMENT

- WHEN WINTER COMES TO MAIN STREET

- THE WOMEN WHO MAKE OUR NOVELS

- WHY AUTHORS GO WRONG AND OTHER EXPLANATIONS

Novels

- THE THOUSAND AND FIRST NIGHT

- ISLAND OF THE INNOCENT

- THE ANSWERER

- WORLD WITHOUT END

- MERMAID

Cargoes

for Crusoes

By GRANT OVERTON

New York: D. Appleton & Company

New York: George H. Doran Company

Boston: Little, Brown, and Company

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

COPYRIGHT, 1924,

BY GRANT OVERTON

First Printing, September, 1924.

Press of

J. J. Little & Ives Company

New York, U. S. A.

Bound in Interlaken-Cloth

“Let’s Give Him a Book.”

“He’s Got a Book.”

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO

ALL THOSE WHO, THOUGH HAVING

ONE BOOK, SOMETIMES ENJOY ANOTHER

Preface

Being a True Account of How a Priceless Cargo Was Delivered to a Desert Islander

How that I, Robinson Crusoe, came to be wrecked with others of the ship’s company on a Desert Island, all being lost save my unworthy self, hath in a precise manner been narrated by one D. Defoe in the book he saw fit to entitle with my name; but his ending is indifferent. For novels like Defoe’s must have the Happy Ending, so styled. Yet is the truth often happier far than fiction. Being no hand to invent a tale, I am content to set down in this place events as I humbly took part in them.

Let me declare, then, that here on my Desert Island I for long suffered great loneliness and consequent distress of soul. This went on many days. Howbeit, while sunk very low in my spiritual state and with expectation nearly gone, a huge ship passing near labored painfully with a storm by the mercy of God being compelled to throw overboard—or, as they say at sea, to jettison—the greater part of her cargo. And being thus lightened she stood away from the Island and went on her course safely. The same storm cast upon the shore the rich treasure wherewith she had been laden, so many wooden boxes or cases, packed tightly and well-lined, which for the most part were washed up undamaged and, within, scarcely dampened except it may be for an inch or two. Coming down to the shore the morning after I stood transfixed with astonishment at the sight of something lying on the sand. It was a book.

When I had a little recovered from my amaze, my joy and ecstasy knew no way to communicate itself, and almost immediately, my eye falling on the cases strewn along the beach, I capered with delight. I brake open the boxes, one after the other fast as I could work. All, all, were brimmed with the newest books!

Since that day I have not lacked instruction and entertainment, and deem that Providence, at trifling expense to the maritime insurers, hath rescued me from boredom forevermore. And this I deem the only rescue worth a fingersnap in this life of ours, and one that a great majority of people do never accomplish. My days and nights have been and yet are filled with most various delights, my walks are taken with a great company of authors and my conversations are held with them.

With such profit and satisfaction do I read that more than once, being sighted by a vessel which then stood by to take me off my Island, I have waved the sailors to proceed without me, which they have done with doubt and difficulty; yet finally I have convinced them of my meaning, they proceeding with their voyage, I with mine....

Contents

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| 1 | THE KNIGHTLINESS OF PHILIP GIBBS | 15 |

| 2 | THE TRAIL BLAZERS | 28 |

| 3 | THE ART OF MELVILLE DAVISSON POST | 41 |

| 4 | JEFFERY FARNOL’S GESTES | 60 |

| 5 | ADULTS PLEASE SKIP | 83 |

| 6 | THE TWENTIETH CENTURY GOTHIC OF ALDOUS HUXLEY | 97 |

| 7 | IN EVERY HOME: A CHAPTER FOR WOMEN | 114 |

| 8 | A GREAT IMPERSONATION BY E. PHILLIPS OPPENHEIM | 126 |

| 9 | G. STANLEY HALL, PSYCHOLOGIST | 143 |

| 10 | THE MODE IN NEW FICTION | 167 |

| 11 | COSMO HAMILTON’S UNWRITTEN HISTORY | 182 |

| 12 | LEST THEY FORGET | 197 |

| 13 | THAT LITERARY WANDERER, E. V. LUCAS | 212 |

| 14 | AMERICAN HISTORY IN FICTION | 232 |

| 15 | THE FIRESIDE THEATRE | 252 |

| 16 | A REASONABLE VIEW OF MICHAEL ARLEN | 266 |

| 17 | PALETTES AND PATTERNS IN PROSE AND POETRY | 277 |

| 18 | COMING!—COURTNEY RYLEY COOPER—COMING! | 290 |

| 19 | EDITH WHARTON’S OLD NEW YORK | 304 |

| 20 | NOT FOUND ELSEWHERE | 314 |

| 21 | FRANK L. PACKARD UNLOCKS A BOOK | 330 |

| 22 | ALL CREEDS AND NONE | 348 |

| 23 | J. C. SNAITH AND GEORGE GIBBS | 363 |

| 24 | MARY JOHNSTON’S ADVENTURE | 375 |

| INDEX OF PRICES | 389 | |

| INDEX | 403 |

Portraits

| PAGE | |

| PHILIP GIBBS | 16 |

| MELVILLE DAVISSON POST | 48 |

| JEFFERY FARNOL | 64 |

| SUSAN ERTZ | 176 |

| COSMO HAMILTON | 184 |

| E. V. LUCAS | 224 |

| EMERSON HOUGH | 234 |

| MICHAEL ARLEN | 272 |

| MARY JOHNSTON | 384 |

Cargoes for Crusoes

CARGOES FOR CRUSOES

1. The Knightliness of Philip Gibbs

i

Then one said: “Rise, Sir Philip——” but the terms in which the still young man received ennoblement were heard by none; for all were drawn by his face in which austerity and gentleness seemed mingled. A pale young man with a nicotine-stained third finger whom Arnold Bennett had once warned authors against (he asks you to lunch and drives a hard bargain over the coffee). A good reporter for Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe. A war correspondent with seven-league boots. A man standing on a platform in Carnegie Hall which rings with riot “looking like a frightfully tired Savonarola who is speaking in a trance.” His thin, uncompromising nose; the jut of the chin; the high cheekbones and the hollow cheeks, long upper lip and mouth with drawn-in, straight corners (yet a compassionate mouth); the deep-set eyes; the ears placed so far back, and the raking line of the jaw—if these were all he might be nothing better than a fine breed of news hound with “points.” They are nothing; but the clear shine of idealism from eye and countenance is the whole man. Great Britain had knighted a reporter, but Philip Gibbs had been born to knighthood.

For when chivalry would have died, he first succored and then revived it; when men wished to forget, he compelled them to remember. He actually proves what men have forgotten how to prove, and so have turned into a copybook maxim. Perhaps the reason his pen is mightier than any sword is because he wields it as if it were one.

In the eyes of the world he is the D’Artagnan of Three Musketeers who are also three brothers. They are Philip (Hamilton) Gibbs, Cosmo Hamilton (Gibbs), and A(rthur) Hamilton Gibbs, the mutations of name arising from choice and even from a certain literary necessity; for an author’s name should be distinctive and is usually better not to be too long. The father, Henry Gibbs, was an English civil servant, a departmental chief in the Board of Education. The mother had been Helen Hamilton. The family at one time consisted of six boys and two girls. Henry Gibbs had “a delicate wife, an unresilient salary, and his spirit of taking chances had been killed by heavy responsibility, the caution and timidity growing out of a painful knowledge of the risks and difficulties of life, and the undermining security of having sat all his working years in the safe cul-de-sac of a government office.”[1] It was the office in which Matthew Arnold worked and in which an obscure temporary clerk, W. S. Gilbert, stole moments to compose some verse called Bab Ballads. Henry Gibbs was a famous after-dinner speaker and it was certainly he who preserved the Carlyle House for London, but the nature of the case forbade him to encourage the marked adventurous strain in his boys.

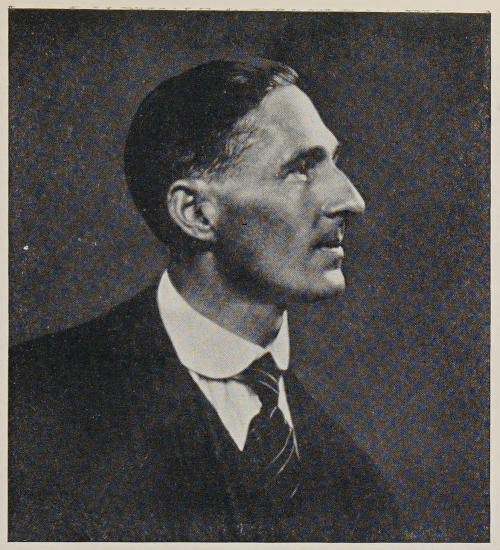

PHILIP GIBBS

Copyright by Underwood & Underwood.

Philip Gibbs was educated privately and was an editor before he was 21. He was, in fact, only 19 when he became “educational editor” for the large English publishing firm of Cassell at a salary of a hundred and twenty pounds a year. “With five pounds capital and that income, I married”—Agnes Rowland, daughter of the Rev. W. J. Rowland—“with an audacity which I now find superb. I was so young, and looked so much younger, that I did not dare to confess my married state to my official chief, who was the Right Honorable H. O. Arnold-Forster, in whose room I sat, and one day when my wife popped her head through the door and said ‘Hullo!’ I made signs to her to depart.

“‘Who’s that pretty girl?’ asked Arnold-Forster, and with shame I must confess that I hid the secret of our relationship.”[2]

He was both timid and bashful; yet like many men of his stamp, he was to show on many occasions a lion-like courage. A hundred and a thousand times he was to pass as close to death as a man may pass and yet live; in general, he was to be quite as badly scared as a chap can be in such circumstances; and without exception he was to persist in what he was doing, for there was and is in him something stronger than fear.

ii

Philip Gibbs’s earlier career differed little from that of Arnold Bennett or the first years of dozens of Englishmen who have made their start in Fleet Street. After several years with Cassell, he applied for and got a job as managing editor of a large literary syndicate. In this post he bought Bennett’s early novel, The Grand Babylon Hotel, and other fiction and articles to be sold to newspapers in Great Britain and the colonies. While with Cassell he had written his first book, Founders of the Empire, a historical text still used in English schools. As a syndicate editor he wrote articles on every conceivable subject, particularly a weekly essay called “Knowledge is Power.” But his job was outside of London, for which he hankered; and finally he wrote to Alfred Harmsworth, who was later to become Lord Northcliffe and who had founded the Daily Mail. The result was a job under a brilliant journalist, Filson Young, whom Gibbs succeeded a few months later as editor of Page Four in the Mail (devoted to special articles). Here he learned all about the new journalism and had a chance to observe Northcliffe closely. In the seventh chapter of his Adventures in Journalism, Philip Gibbs gives a brief but well-etched portrait of the man who transformed the character of the English newspaper. Northcliffe’s genius, his generosity, his ruthlessness—which was often the result of indifference and sometimes sprang from fatigue and bad temper—are very well conveyed in a half dozen pages. Gibbs suffered the fate of nearly all this man’s temporary favorites. When he was dismissed from the Daily Mail he went for a few months to the Daily Express before beginning what was to be a long association with the Daily Chronicle.

His connection with the Chronicle was broken by the sad experiment of the Tribune, a newspaper founded by a melancholy young man named Franklin Thomasson as a pious carrying out of his father’s wishes. As literary editor of this daily, Philip Gibbs bought work by Rudyard Kipling, Joseph Conrad and Gilbert K. Chesterton, but the paper as a whole was dull and doomed. When it went down, Philip Gibbs thought he saw a chance to throw off the bondage of offices. He took his wife and little son and retreated to a coast-guard’s cottage at Littlehampton. “There, in a tiny room, filled with the murmur of the sea, and the vulgar songs of seaside Pierrots, I wrote my novel, The Street of Adventure, in which I told, in the guise of fiction, the history of the Tribune newspaper, and gave a picture of the squalor, disappointment, adventure, insecurity, futility, and good comradeship of Fleet Street.” There was need of money, but the novel cost Gibbs more than it earned. His narrative had not disguised sufficiently either the newspaper or members of its late staff. The point is a little difficult for American readers to take in, and rests on English libel law, which is quite different from the American. In England, “the greater the truth, the greater the libel.” A libel action was instituted, and although it was finally withdrawn, the bills of costs were heavy and the sale had been killed. But when published in the United States after the war, The Street of Adventure had a very good success.

“I knew after that the wear and tear, the mental distress, the financial uncertainty that befell a free lance in search of fame and fortune, when those mocking will-o’-the-wisps lead him through the ditches of disappointment and the thickets of ill luck. How many hundreds of times did I pace the streets of London in those days, vainly seeking the plot of a short story, and haunted by elusive characters who would not fit into my combination of circumstances, ending at 4,000 words with a dramatic climax! How many hours have I spent glued to a seat in Kensington Gardens, working out literary triangles with a husband and wife and the third party, two men and a woman, two women and a man, and finding only a vicious circle of hopeless imbecility! At such times one’s nerves get ‘edgy’ and one’s imagination becomes feverish with effort, so that the more desperately one chases an idea, the more resolutely it eludes one.”[3]

Yet he counts himself, on the whole, to have been lucky. He was able to earn a living and to give time and labor to “the most unprofitable branch of literature, which is history, and my first love.” Years later he was to have a thrill of pleasure at seeing in the windows of Paris bookshops his Men and Women of the French Revolution, magnificently illustrated with reproductions of old prints. He wrote the romantic life of George Villiers, First Duke of Buckingham, and discovered in the murder of Sir Thomas Overbury “a plot with kings and princes, great lords and ladies, bishops and judges, poisoners, witch doctors, cut-throats and poets,” the incomparable material for his King’s Favorite. These books brought him only a few hundred dollars apiece, though perhaps more in reputation and friendships.

iii

He returned to journalism, eventually, as special correspondent and descriptive writer for the Daily Chronicle. He was rather frequently in charge of the Paris office and had all sorts of adventures in that city, both those derived from saturating himself in French history and others incident to his daily work. After the Portuguese revolution he was sent to Portugal to explore the condition of those political prisoners that the republicans had in some cases interred alive. His greatest feat was the revelation of Dr. Cook’s fraud in claiming the discovery of the North Pole. This was a triumph of sheer intuition, in the first instance, and both dogged persistency and remarkable courage were necessary before Philip Gibbs could be proved right.

It began with a late start, twenty-four hours behind the other correspondents. When Gibbs got to Copenhagen, the vessel bringing Dr. Cook had not arrived, owing to fogs. Through a chance meeting in a restaurant with Mrs. Rasmussen, wife of the explorer, Gibbs got to Elsinore and aboard a launch which was putting out to meet the delayed ship. Thus he was the only English-speaking person present at the first interview, on shipboard. As it happened, Dr. Cook had not yet acquired that magnificent poise and aplomb which he was to display from the moment he set foot ashore. His eyes evaded Gibbs, he explained that he had no papers to prove his claim and not even a diary, and when pressed for some sort of written record or notes he exclaimed: “You believed Nansen and Amundsen and Sverdrup. They had only their story to tell. Why don’t you believe me?” Later Cook had a moment of utter funk, hiding in his cabin. It passed quickly and after that he was outwardly all that a hero should be.

But Gibbs had had his chance. His seven-column story to the Daily Chronicle caused him to be denounced everywhere and even put him in jeopardy of his life in Copenhagen; yet a few weeks were to show it to be one of the greatest exclusive newspaper stories, “beats” or “scoops,” ever written.

iv

In September, 1912, war started in the Balkans. Gibbs went as a correspondent and this experience, lamentable and laughable, comical and extremely repellent, was his first direct preparation for work soon to follow. The year following he had occasion to go to Germany and study the state of mind, popular and official, toward England. He was, therefore, exceptionally well fitted to be a correspondent at the front when the World War began. It would be impossible as well as improper to try to abbreviate here the story of his experience told so brilliantly and with so much movement (and with far too much modesty) in his Adventures in Journalism. At the outset of the war no newspaperman had any official standing. The correspondent was unrecognized—or it would be more accurate to say that he was recognized only as a dangerous nuisance, subject to arrest at sight. Gibbs and two other very distinguished newspapermen, H. M. Tomlinson and W. M. Massey, worked together for weeks and months and were three of a small group of correspondents who risked their lives constantly in the war zone and their liberty on every occasion when they stepped out of it. There came a time when the game seemed to be up. “I had violated every regulation. I had personally angered Lord Kitchener. I was on the black books of the detectives at every port, and General Williams solemnly warned me that if I returned to France I would be put up against a white wall, with unpleasant consequences.”[4] The solution came with the appointment of five official war correspondents, of whom Gibbs was one from first to last. These men covered the war, not for one newspaper but for the newspapers of Great Britain and America. They were attached to General Headquarters and among the men of distinction who were assigned to them as friends, advisers and censors was C. E. Montague, editor of the Manchester Guardian and author of Disenchantment, Fiery Particles, A Hind Let Loose, etc., a meditative writer of exquisite prose who, at the outbreak of the war, had dyed his white hair black, enlisted as a private, served in the trenches, reached the rank of sergeant, finally surviving when the dugout which sheltered him was blown up....

After the war the five correspondents received knighthood, and Philip Gibbs is properly Sir Philip Gibbs, K. B. E. (Knight of the British Empire). On journalistic commissions he visited Ireland and Asia Minor and revisited most of the countries of Europe, including Russia. He came to America twice to lecture on the war and conditions resulting from it, and his book, People of Destiny, is a critical but admiring account of America as he found it. Pope Benedict XV., against all precedent, accorded Gibbs an interview on the reconstruction of Europe and this interview was naturally printed in all the principal newspapers of the world. He had become, more truly than any other man has ever been, more fully than any other man is, the world’s reporter. His title was splendidly established by his summarizing book on the war, Now It Can Be Told, and was strikingly reëmphasized with his novel, The Middle of the Road, concerning which a few words are in order.

v

Although Philip Gibbs had published, in 1919, a novel, Wounded Souls, which contains much of the message of The Middle of the Road, the world was not ready for what he had to tell. He therefore set to work on a canvas which he determined should include all Europe. His visits to Ireland, France, Germany and even Russia had placed at his disposal an unparalleled mass of authentic firsthand material. He knew, better than most, what existed, and what lay immediately ahead. Using fiction frankly as a guise to present facts, both physical facts and the facts of emotion and attitude, he wrote his story.

When the novel was published in England and the United States at the beginning of 1923 it leaped into instant and enormous popularity. This was partly the result of prophetic details, such as this speech of one of the characters (from page 317 of The Middle of the Road):

“‘France wants to push Germany into the mud,’ said Dorothy. ‘Nothing will satisfy her but a march into the Ruhr to seize the industrial cities and strangle Germany’s chance of life.’”

When the novel was published the French invasion of the Ruhr had just begun.

There was a sense of larger prophecy that hovered over the story. But even more of the instant success of the book was due to the terrible picture it painted, minute yet panoramic, ghastly but honest. People sat up, literally, all night to finish the book. People read it with tears running from their eyes, with sobs; they went about for days afterward feeling as if a heavy blow had stunned them, a blow from which they were only slowly recovering. Although every effort was made in advance of publication to insure attention for the book, it is doubtful whether such effort counted at all in the book’s success. For none who read it failed to talk about it in a way that fairly coerced others to become Philip Gibbs’s readers. Month after month the sale of this book rolls on. It is not, as a piece of literary construction or considered as literary art, a good novel; it is something much bigger than that—a piece of marvelous reporting and a work of propaganda charged to the full with humane indignation and pity and compassion.

vi

As if he had found his field at last in the roomy spaces and manifold disguises of the novel, Philip Gibbs followed The Middle of the Road with a very keenly-observed study of young people. Heirs Apparent deals with the generation which was too young to take any active part in the World War but which has come to a somewhat unformed maturity since. The gayety of the novel does not prevent the author, with his usual thoroughness, from presenting the more serious aspects of his young people’s misbehavior. There is incidentally an exactly drawn study of that newer, sensational journalism which Philip Gibbs tasted under Northcliffe and which is familiar enough, though on the outside only, to most Americans. But the delightful thing about Heirs Apparent is the author’s unfailing sympathy with his youngsters; and the optimism of the ending—the book closes with a character’s cry: “Youth’s all right!”—is the sincere expression of Philip Gibbs’s own perfect faith.

The tales in his new volume, Little Novels of Nowadays, are brothers to The Middle of the Road. What proportion of these stories is fact and what fiction is irrelevant, since in atmosphere and emotion all are true. Each of these poignant pieces is a document of the calamitous war more significant to humanity than the treaty sealed at Versailles. Whether in Russia or stricken Budapest or flaming Smyrna or some far-off corner of lonely starvation, Philip Gibbs has seen all, felt all ... and can convey all.

vii

In fine, a bigger man than any of his books. One of the greatest reporters the press has ever had, one of the half-dozen—if so many—best masters of descriptive writing now alive. A chap who suffered nervous breakdowns prior to 1914 and who turned to iron in the moment of crisis. A militant pacifist because he has really seen war waged. A lover and fighter for justice, and a preacher of mercy. There is about him, despite the abolition of miracle and the rapid transformation of the world into a factory and a machine, some of that lost radiance of a day when men set forth to conquer in the name of their faith, or to spread a gospel which might redeem the world.

BOOKS BY PHILIP GIBBS

Fiction:

| 1908 | The Individualist |

| 1908 | The Spirit of Revolt |

| 1909 | The Street of Adventure |

| 1910 | Intellectual Mansions, S. W. |

| 1911 | Oliver’s Kind Women |

| 1912 | Helen of Lancaster Gate |

| 1913 | A Master of Life |

| 1914 | Beauty and Nick |

| In England: The Custody of the Child | |

| 1920 | Wounded Souls |

| In England: Back to Life | |

| 1922 | Venetian Lovers |

| 1923 | The Middle of the Road |

| 1924 | Heirs Apparent |

| 1924 | Little Novels of Nowadays |

Historical:

| 1899 | Founders of the Empire |

| 1906 | The Romance of Empire |

| 1906 | Men and Women of the French Revolution |

| 1908 | The Romance of George Villiers, First Duke of Buckingham |

| 1909 | King’s Favorite |

| 1912 | Adventures of War with Cross and Crescent |

| 1915 | The Soul of the War |

| 1917 | The Battles of the Somme |

| 1918 | The Struggle in Flanders |

| First title: From Bapaume to Passchendaele | |

| 1919 | The Way to Victory |

| In England: Open Warfare | |

| 1920 | Now It Can Be Told |

| In England: Realities of War | |

| 1920 | People of Destiny |

| 1921 | More That Must Be Told |

| In England: The Hope of Europe | |

| 1924 | Adventures in Journalism |

Essays:

| 1903 | Knowledge Is Power |

| 1905 | Facts and Ideas |

| 1913 | The Eighth Year: A Vital Problem of Married Life |

| 1913 | The New Man: A Portrait of the Latest Type |

SOURCES ON PHILIP GIBBS

His Adventures in Journalism is autobiographical in the best sense of the word, and only needs to be supplemented by the formal particulars in Who’s Who (England). There are interesting references in Cosmo Hamilton’s Unwritten History. For a not wholly friendly reference, see Clement K. Shorter’s page in The Sphere, London, for 6 October 1923. Mr. Shorter was one of a few who believed themselves libelled in The Street of Adventure, and he has had various literary feuds.

Address: Sir Philip Gibbs, Ladygate, Punch Bowl Lane, Dorking, England.

2. The Trail Blazers

i

These paths are strange and exciting. One leads into the midst of wild beasts, another into the depths of the sea. A third goes laboriously some few feet underground and erases three thousand years in three months. One or two, keeping to the present, are sources of innocent merriment; several employ the mode of fiction to vivify fact; and at least one is a continuous pageant in colors of the American West.

There is no order in which these paths are to be taken; you may go half across the world to follow one, or you may begin by merely stepping outside your door. America or Arabia, ferns or fishes, dogs or diggings, history, hunting ... outdoor books are the best of indoor sports.

The alphabet is an immense convenience and I start with Adventurousness and America. For some time Joseph Lewis French has been busy selecting from various American authors the best accounts of the discovery of gold in California, the days of the pony express and the stage coach, the cowboy, the trapper, the guide, the bad man, and other phases of our history. He has drawn upon the works of Francis Parkman, Mark Twain, Bret Harte, Hamlin Garland, Bayard Taylor, General George A. Custer, Owen Wister, Theodore Roosevelt, Emerson Hough and a good many others in the task. Mr. French calls his book The Pioneer West: Narratives of the Westward March of Empire, and Hamlin Garland has written a foreword for it. Also Remington Schuyler has done illustrations in color. As an anthology, the volume has no exact parallel in my knowledge. The nuggets it contains are otherwise for the most part found with considerable difficulty in half a hundred somewhat inaccessible places. It is, for example, not easy to find what you want in either Parkman or Roosevelt without risking a long hunt; and books by other earlier writers, even one so perfectly well-known as Bayard Taylor, are often hard to come by. It is no wonder that Mr. Garland calls The Pioneer West a real service in recovery. Mr. French spreads a satisfactory panorama before the reader, for his selected narratives run from the time of Lewis’s and Clark’s discovery of Oregon down to the last of the Indian uprisings.

A projected alliance between the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Russian American Fur Company led, in 1867, to a great piece of foolishness on the part of an American Secretary of State. Congress was induced to pay some millions of dollars to purchase a fancy refrigerator and everyone was scornful of “Seward’s folly.” Edison Marshall has taken the phrase for the title of his new novel dealing with that period in Alaskan history. Seward’s Folly relates how Major Jefferson Sharp, late of the army of the Confederate States of America, was sent to Sitka by Seward. Major Sharp liked an aristocratic society, and he found it in Sitka where Russians, Englishmen, Americans and Indians were colorfully combined. He also encountered, in Molly Forest and her uncle, two Americans undisturbed by any doubts as to the superiority of American character and the value of American ideas of liberty and opportunity.

The fact that Major Sharp was still loyal to the spirit of the Confederacy and had no intention of serving the Union did not tend to simplify matters. He was, however, no scoundrel; and he came to recognize, beneath the glitter of Alaskan surfaces, much that his nature could not countenance. Mr. Marshall has managed an extremely good story. But he has brightened a portion of history in doing so.

William Patterson White’s The Twisted Foot and B. M. Bower’s The Bellehelen Mine are novels of the cattle rancher and the miner, respectively. Mr. White’s story has almost every ingredient of an exciting yarn—a love interest, an independent young woman who doesn’t believe in explanations, a mystery, an open enemy, a set of foes whose methods are mean and underhanded, and a couple of young men who think quick and shoot quick. The impetuous Buff Warren, cowboy, is sent to drive off the range a family of “nesters.” He finds that the father is blind and that the family is making a very brave fight against severe odds. He also meets Gillian Fair. Instead of putting the Fairs off the range, Buff takes them under his protection. This means the loss of his job, and when, by a trick, he gets himself made deputy sheriff, his state of mind is not helped by the fact that all clues to a bandit who is terrorizing the region seem to lead to Gillian Fair.

B. M. Bower tells of a silver mine named by a prospector after his two baby daughters, one of whom, grown to womanhood, is the heroine of The Bellehelen Mine. Helen Strong, left alone to carry out plans that she and her father had made together, returns to Goldfield and assembles a crew from among her father’s old miners. It is the beginning of an unanticipated battle, for the Western Consolidated is determined to make Helen Strong sell out.

The Bellehelen Mine is to an extent a departure from the author’s previous books, a story of mine-working and not of ranch life. But it should be realized that B. M. Bower, or Mrs. Cowan, has been for some years a mine owner and manager. It would be surprising if she did not use this phase of her experiences in her fiction. She lives at El Picacho Mine, Las Vegas, Nevada; and after twenty years of writing Western fiction it is high time she gave us a mining story.

B. M. Bower is a woman but by no means a tenderfoot. Mary Roberts Rinehart’s account of her tenderfootage, in The Out Trail, is the most amusing record of a woman in the West on my shelf of recent books. But the most amusing record of America in general is, I think, Cobb’s America Guyed Books, that series of small volumes with drawings by John T. McCutcheon, a book to each State. These attach themselves with a burr-like tenacity to the memory in a series of epigrams. You remember that Irvin S. Cobb said of New York City: “So far as I know, General U. S. Grant is the only permanent resident,” and of Indiana: “Intellectually, she rolls her own,” and of Kansas: “A trifle shy on natural beauties, but plenty of moral Alps and mental Himalayas.” Such priceless remarks are more to be cherished—and are more cherished—than State mottoes; but the Guyed Books have a claim to respect as well as affection. Each presents, along with various State demerits, partly humorous and partly real, the honest claim of the people of one section to be considered as individual, characterizable, with a personality not lost in the American mass. And Mr. Cobb has not failed to give the people of each State credit for State achievement.

Yet, because they contain humor, the Guyed Books will always be classed as works of humor. A little leaven is a dangerous thing. On the other hand, a little knowledge leaveneth the whole lump. Donald Ogden Stewart has that little knowledge, and the result is the perfection of his new work, Mr. and Mrs. Haddock Abroad. It is the fault of authors of books of family life that they almost always know too much. Mr. Stewart (as reviewers say) has avoided this shortcoming. And in fiction, as in any other game, the element of surprise is invaluable. Surprise, conjecture, suspicion—especially suspicion! It was because she was above suspicion that Caesar’s wife was not well received in the best Roman circles. Mr. and Mrs. Haddock Abroad would have helped her.... But, all seriousness for once aside, Mr. Stewart’s treatise on the American family unit is masterly. It will give Americans a new status in Paris. There are many irrelevances and illustrations throughout the book.

ii

Five—usually five and a fraction—per cent. of the people in any community are confirmed fishermen. The greatest living authority on fishes is David Starr Jordan, for so many years president of Leland Stanford Junior University. He is the author of the most important book on its subject, a piscatorial Bible, in fact, which now appears in a new revised edition. It has forty-six chapters, and 673 illustrations, of which eighteen are full-page plates in color. It is by Dr. Jordan, now a man past seventy. Its title is Fishes. It has no other title, and no subtitle. It needs none.

This marvellous book makes the heart leap as the trout leaps. Nothing so delightful or complete is found elsewhere. One may know nothing about fishes—I don’t—and yet turn these pages in a perfect enchantment. I suppose, in a way, it is the emotion of a first youthful visit to the Aquarium, but an emotion incredibly magnified. Dr. Jordan speaks of his volume with what must seem to the reader a ridiculous modesty. He says it is a non-technical book that may still be valuable to those who are interested in the study of fishes as science. He says his chief aim has been “to make it interesting to nature-lovers and anglers, and instructive to all who open its pages. The fishes used as food and those caught by anglers in America are treated fully, and proportionate attention is paid to all the existing as well as all extinct families of fishes.” This may be true, but it no more explains the book than a conjuror’s account explains his magic.

Beginning with the fish as a form of life, Dr. Jordan goes through every attribute of fishes and then, in an incomparable sequence, tells what we know of each species. There are chapters like that on the distribution of fishes which seem to transform the world in somewhat the fashion in which Jules Verne’s Captain Nemo transformed it; other chapters, like that on the fish as food, are of vital importance; and such a chapter as that on the mythology of fishes (including the sea serpent) have a charm irresistible and without equal. At length one plunges into the sea, swimming through a myriad of sea creatures whose very names—elasmobranchii or shark-like fishes, the salmonidae, the mailed-cheek fishes, the dactyloscopidae—are as curious and as evocative as those strange shapes that float in green water behind aquarium glass.

Dr. James A. Henshall’s Book of the Black Bass, an acknowledged masterpiece, is practically a new book as the result of rewriting and enlargement. Nearly all the illustrations, including those in color, are new. In addition to a complete scientific and life history of the fish, Dr. Henshall gives the last word regarding tools and tackle for catching what is “inch for inch and pound for pound the gamest fish that swims.”

Let us continue for a little with the authorities on these very special subjects of sport. Dr. William A. Bruette is one on dogs. He is well-known as the editor of Forest and Stream, and various particular books on the dog—or perhaps I should say, on particular dogs—preceded The Complete Dog Book. There is not an opportunity for anything of its sort to follow it unless some one may be moved to write a canine encyclopædia in some number of volumes. For The Complete Dog Book—illustrated with photographs, of course—describes the dogs of the world and very fully describes all the breeds recognized by the American Kennel Club. It is, throughout, a carefully comparative description, giving the standards for judging each breed and the good and bad points of each. The care of dogs in health and their treatment in disease, as well as their training and general management are gone over in detail; but Dr. Bruette’s prime service is his wisdom on the subject of buying puppies. Here are the pages which will save the reader most, both in dollars and disappointment.

Birds are hard to learn, not easy to observe, and must be taken largely on trust for an acquaintance. On the other hand, if you will take George Henry Tilton’s The Fern Lover’s Companion with its 188 illustrations, go over it carefully, use its glossary of terms and keep an eye about you in your walks, you may learn the names and the chief characteristics of our most common ferns in a single season. There is about ferns something of the fascination there is in fishes—a great variety of form, and forms of exquisite coloration and beauty of pattern. Mr. Tilton’s handbook is progressive; if consulted attentively, it can be followed from beginning to end without confusion or the need of going again over the same ground. Ground in the book, I mean!

When it comes to covering ground, Charles C. Stoddard’s Shanks’ Mare is a superior article. This book about walking—really, about the joys of walking—moves without haste and with an easy rhythm of prose and sentiment. It is one of the few books that have the impelling quality of fine spring weather. As Stewart Edward White said: “That is the main thing—to get ’em out.” The remark occurred in a letter to Dr. Claude P. Fordyce, a letter which forms the introduction to Dr. Fordyce’s capital book on Trail Craft. “I am glad you are publishing the book,” wrote Mr. White. “All your articles on the out-of-doors life have seemed to me practical, sensible, and the product of much experience, plus some discriminative thought.” He followed his words about getting people out of doors with: “If, in addition, you can give them hints that will, through their interest or comfort, keep ’em out, the job is complete.” Trail Craft will do a finished job for a good many who read it. Dr. Fordyce has the considerable advantage of knowing American wildernesses; he writes with equal knowledge of practical mountaineering and desert journeys; tenting, motor camping, the use of balloon silk in camp, camera hunting, medical improvization, even the possibilities of leather working for the outdoor man are included in Trail Craft.

What percentage of American vacations are now accomplished with the aid of the automobile must be left for the census of 1930 to determine; but it is large, and will be larger then. In fact, motor camping is a distinct department of a magazine like Outers’ Recreation, attended to along with other editorial duties by F. E. Brimmer, whose Autocamping is rather more necessary than the Blue Book. For a missed road is remediable, but a non-existent hotel isn’t. Besides, a hotel isn’t camping.

Having lived outdoors with his family, including small children, for as long as five consecutive months, Mr. Brimmer has met most of the contingencies you will have to meet. Autocamping is the difference between a vacation and a disaster.

Here are two short works of fiction by one of the best living storytellers whose subjects are drawn from sport. A Wedding Gift, by John Taintor Foote, is annotated by its subtitle, “A Fishing Story.” Mr. Foote’s Pocono Shot needs no recommendation to those who know his fine dog story, Dumb-Bell of Brookfield. A Wedding Gift is the tale of a confirmed fisherman, aged forty, who marries a young and beautiful girl. The story is told by a friend whose wedding gift to the pair consisted of hand-painted fish plates each with a picture of a trout rising to take a fly. The bride had packed three trunks with frilly clothes in expectation of a honeymoon at Narragansett. She was wrong. She was taken to the Maine woods.

The narrative of what followed is of such a character that the fisherman’s friend, having heard him out and remembering the dozen plates, each with a trout painted on it, does not wait to meet the bride.

A Wedding Gift is pure amusement, if you like, but Pocono Shot is written with an emotion that the reader feels whether he cares for dogs or not. It has also—owing, perhaps, to its being told in the first person—an accent of reality. The dog of the story is a black and white setter, the best bird dog in the Pocono Hills, and better on a scent than any hound in the country round about. It was this aptitude which got Pocono Shot into trouble; tracking a man who had caused the death of a girl, the setter received a terrible axe wound from the fugitive’s father. The dog is marked by a great shoulder scar. We make acquaintance with his history at this point, step back for a little to learn his career, go with him in the field and find out for ourselves his extraordinary qualities, and then follow him to his reunion with the master who had shot to kill when the setter’s life was imperilled.

iii

Surely the most exciting trail blazed in our day was the short and obscure one leading a few feet underground which took Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon into Tut-Ankh-Amen’s royal chamber. The second volume of Howard Carter’s and A. C. Mace’s The Tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amen, now impending, will round out the record of a discovery which exists, and is likely to remain, without parallel. The odds against a similar find are too great for anyone but a mathematician to calculate, and would be meaningless in any calculation. The first volume of The Tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amen surpassed most other official and authentic records of its sort simply because the authors forgot they were archæologists and—told the story. In the presence of that priceless gift of fortune, standing where they had stood and breaching a blank wall to find it the threshold of the inner chamber with its nested gold shrines, who could have thought of anything but the supreme human and dramatic values of that scene and fateful moment? Not Howard Carter, certainly. He remembered then the six long and barren years of unrewarded searching, the first faint hint that he might be on the right track, the mounting excitement chilled at regular intervals by the worry of doubt and the littleness of disappointed hopes. Yet here lay a king of Egypt, his body cased in gold and his tomb and its seals protected by his gods. It was a story that could not be told except in all its simplicity. One could no more dress it up in lore and learning than permit the excesses of emotional description. The Tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amen is the modern romance of the conquistador.

While we are on the path of adventure in strange lands I want to draw attention to a book which transcends the interests of sportsmen. A fourteen-year-old boy, a circus trainer of animals, Dr. W. T. Hornaday, of the New York Zoo, Courtney Ryley Cooper, the novelist, and in fact persons of all ages and occupations will find themselves utterly absorbed in the pages of A. Blayney Percival’s A Game Ranger’s Note Book. This handsome book, illustrated with photographs, has been arranged and edited by E. D. Cuming from the great mass of observations, both written and verbal, made by Mr. Percival during nearly thirty years spent in Africa, of which about twenty-two were passed in the Game Department of what is now the Kenya Colony. It opens with seven chapters on the lion, followed by one or more chapters apiece on the leopard; cheetah, serval and caracal (one chapter); hunting dogs; hyænas; elephant; rhinoceros; hippopotamus; buffalo; giraffe; swine; zebra, and antelope. Most of Mr. Percival’s material about the antelope has had to be reserved for a separate volume, so copious is it. The book closes with chapters on hunting and photographing big game. It is utterly untechnical, extremely modest, occasionally humorous, and as meaty with thrills as with information about animal characteristics and habits. A Game Ranger’s Note Book deserves as a pendant in reading Fred L. M. Moir’s After Livingstone, a story of adventure and hunting when big game were more numerous than now. The story is told by one of two brothers, business men who were pioneer traders in Africa. It has plenty of bush fighting and Mr. Moir witnessed scenes of savage life that will probably never come within the experience of white men again.

GOING OUT?

Birds of America, edited by T. Gilbert Pearson, John Burroughs, Herbert K. Job and others. Three volumes. Describes and pictures 1,000 species. Over 300 species shown in color from New York State Museum drawings. Eggs of 100 species in actual size and colors.

The Outdoorsman’s Handbook, by H. S. Watson and Capt. Paul A. Curtis, Jr. Tested wisdom on hunting, camping, fishing and woodcraft. Indexed.

Lake and Stream Game Fishing, by Dixie Carroll. The author was at the time of his death recently probably the best known fisherman in the United States.

Goin’ Fishin’, by Dixie Carroll. Pungently written and especially good on the subject of baits. Equally interesting to the expert and the occasional angler.

Streamcraft: An Angling Manual, by Dr. George Parker Holden. Endorsed by Stewart Edward White and pronounced by Henry van Dyke “the best of all modern books on the science of trout-fishing.”

Casting Tackle and Methods, by O. W. Smith. Forty years’ experience condensed by the fishing editor of Outdoor Life and author of Trout Lore.

The Salt Water Angler, by Leonard Hulit, is an invaluable and complete compendium of information for salt water fishermen.

In the Alaska-Yukon Gamelands, by J. A. McGuire. The story of an expedition to gather museum specimens far off the beaten routes. Probably the best authority on the game resources of the territory.

Fishing with a Boy, by Leonard Hulit. The tale of a city man in search of health with, incidentally, much about the ways of the humbler fishes.

Jist Huntin’, by Ozark Ripley. Stories told by an expert guide who has fished and hunted from Alaska to the Gulf of Mexico.

Breaking a Bird Dog, by Horace Lytle. Altogether unique is this fascinating account of the process of training, from the author’s actual experiences.

What Bird is That? by Frank M. Chapman. The most recent Chapman bird book. Handily divided according to season; every bird pictured in colors.

Handbook of Birds of Eastern North America, by Frank M. Chapman. A standard work, invaluable to the bird lover.

3. The Art of Melville Davisson Post

i

Who that read in the Saturday Evening Post of 18 July 1914 a short story called “The Doomdorf Mystery” forgets it now? No one, I think; and it was a very short story, and it appeared over ten years ago. The magazine which published it—if one had read no others—has published 2,500 short stories since. “The Doomdorf Mystery” is one in a thousand, literally.

The creature, Doomdorf, in his stone house on the rock brewed a hell-brew. “The idle and the vicious came with their stone jugs, and violence and riot flowed out.” On a certain day two men of the country rode “through the broken spine of the mountains” to have the thing out with Doomdorf. “Randolph was vain and pompous and given over to extravagance of words, but he was a gentleman beneath it, and fear was an alien and a stranger to him. And Abner was the right hand of the land.”

About the place were two persons, a circuit rider who had been rousing the countryside against Doomdorf and who had called down fire from heaven for the creature’s destruction. A little faded woman was the other.

In his chamber, the door bolted from the inside according to custom, Doomdorf lay shot to death.

The circuit rider asseverated that heaven had answered his prayer. The little, frightened, foreign woman showed a crude wax image with a needle thrust through its heart. She had killed Doomdorf by sorcery.

Randolph exclaimed with incredulity. Murder had been done; he was an officer of justice. But Abner pointed out that when the shot was fired, by evidence of Doomdorf’s watch, the circuit rider was on his way to the place, the woman on the mountain among the peach trees. The door was bolted from the inside, the dust on the casings of the two windows was undisturbed and the windows gave on an hundred-foot precipice as smooth as a sheet of glass. Had Doomdorf killed himself? And then got up and put the gun back carefully into the two dogwood forks that held it to the wall? Says Abner: “The murderer of Doomdorf not only climbed the face of that precipice and got in through the closed window, but he shot Doomdorf to death and got out again through the closed window without leaving a single track or trace behind, and without disturbing a grain of dust or a thread of cobweb.... Randolph, let us go and lay an ambush for this assassin. He is on the way here.”

This masterly tale, so far as the explanation is concerned, could doubtless have been chanced upon by Melville Davisson Post in those old records which he, a lawyer, would need to consult. Its kernel or nubbin could spring from the simplest scientific knowledge, the acquisition of any boy in high school. Its marvellous art is another affair. One might have the explanatory fact and make no more of it than a curious coroner’s case. One could narrate it without any use of imagination and the result would be a coincidence without meaning.

The manner of Doomdorf’s assassination depends very greatly upon coincidence. But given the series of coincidences, it was due to the operation of a natural law. Mr. Post had, initially, two difficulties to overcome. The first was fiction’s rule of plausibility. The second was art’s demand for emotional significance, a more-than-meets-the-eye, a meaning.

ii

Truth is stranger than fiction dares to be. Truth compels belief, fiction must court it. To overcome the handicap imposed by the manner of Doomdorf’s killing with its conspiracy of chances, Mr. Post plunges his reader[5] at once into coincidences far more improbable—the presence on the scene of the circuit rider, the double confession of circuit rider and the woman to having killed Doomdorf. He storms the reader’s stronghold of unbelief, the wall is breached, and no Trojan Horse is necessary later to bring his secret into the city. In fiction, there is no plausibility of cause and effect outside human behavior. The implausible (because unmeaning) manner of Doomdorf’s death is superbly supported by two flanks, the behavior of the evangelist and the behavior of a terrified, superstitious and altogether childlike woman.

Art’s demand for meaning requires much more than a certain plausibility of occurrence. The manner of Doomdorf’s death need not have been dependent on his evildoing; it must be made to seem so. The glass water bottle standing on the great oak table in the chamber where he slumbered and died could as easily have held water as his own raw and fiery liquor. There are two kinds of chance or coincidence in the world. One kind is meaningless; our minds perceive no cause and effect. The other kind is that in which we see a desired cause and effect. The writer of fiction must avoid or overcome the first kind if he is to write plausibly and acceptably; but upon his ability or inability to discern and employ the second kind depends his fortune as an artist.

In other particulars “The Doomdorf Mystery” exemplifies the artistry of the author. If I have not emphasized them, it is because they are cunning of hand and brain, craftsmanship, things to be learned, technical excellences which embellish but do not disclose the secret of inspiring art. The story is compactly told; tension is established at once and is drawn more tightly with every sentence; and the element of drama is much enhanced by the forward movement. Doomdorf is dead, but “Randolph,” says Abner, “let us go and lay an ambush for this assassin. He is on the way here.” Not what has happened but what is to happen constitutes the true suspense. The prose style, by its brevity and by a somewhat Biblical diction, does its part to induce in the reader a sense of impending justice, of a divine retribution upon the evildoer. But it is also a prose that lends itself to little pictures, as of the circuit rider, sitting his big red-roan horse, bare-headed, in the court before the stone house; or of the woman, half a child, who thought that with Doomdorf’s death evil must have passed out of the world; or of Doomdorf in his coffin with the red firelight from the fireplace “shining on the dead man’s narrow, everlasting house.” The comparative loneliness, the wildness, and the smiling beauty of these mountains of western Virginia are used subtly in the creation of that thing in a story which we call “atmosphere” and the effect of which is to fix our mood. The tale is most economically told; the simplest and fewest means are made to produce an overwhelming effect. I have dwelt on it at length because it so perfectly illustrates the art of Melville Davisson Post, so arrestingly different from that of any of his contemporaries—different, perhaps, from anyone’s who has ever written.

iii

Mr. Post is one of the few who believe the plot’s the thing. He has said: “The primary object of all fiction is to entertain the reader. If, while it entertains, it also ennobles him this fiction becomes a work of art; but its primary business must be to entertain and not to educate or instruct him. The writer who presents a problem to be solved or a mystery to be untangled will be offering those qualities in his fiction which are of the most nearly universal appeal. A story should be clean-cut and with a single dominating germinal incident upon which it turns as a door upon a hinge, and not built up on a scaffolding of criss-cross stuff. Under the scheme of the universe it is the tragic things that seem the most real. ‘Tragedy is an imitation, not of men, but of an action of life ... the incidents and the plot are the end of a tragedy.’[6] The short story, like any work of art, is produced only by painstaking labor and according to certain structural rules. The laws that apply to mechanics and architecture are no more certain or established than those that apply to the construction of the short story. ‘All art does but consist in the removal of surplusage.’[7] And the short story is to our age what the drama was to the Greeks. The Greeks would have been astounded at the idea common to our age that the highest form of literary structure may omit the framework of the plot. Plot is first, character is second.”[8]

Mr. Post takes his stand thus definitely against what is probably the prevailing literary opinion. For there is a creed, cardinal with many if not most of the best living writers, which says that the best art springs from characterization and not from a series of organized incidents, the plot;—which says, further, that if the characters of a story be chosen with care and presented with conviction, they will make all the plot that is necessary or desirable by their interaction on each other. An excellent example of this is such a novel as Frank Swinnerton’s Nocturne or Willa Cather’s A Lost Lady. Yet it is not possible to refute Mr. Post by citing such books for he could easily point to other novels and stories if modesty forbade him to name his own work. Though there cannot and should not be any decision in this matter, for both the novel of character and the novel of incident are proper vehicles, it is interesting to consider plot as a means to an end.

The Greeks used plot in a manner very different from our use today. At a certain stage toward the close of a Greek tragedy the heavens theoretically opened and a god or goddess intervened, to rescue some, to doom others of the human actors. The purpose was to show man’s impotence before heaven, but also to show his courage, rashness, dignity and other qualities in the face and under the spell of overwhelming odds. The effect aimed at by the spectacle of Greek tragedy was one of emotional purification, a purging away in the minds of the beholders of all petty and little things, the celebrated katharsis as it was called.[9] To the extent that modern fiction aims to show man’s impotence in the hands of destiny or fate, his valiance or his weak cowering or his pitiful but ineffectual struggle, the use of plot in our day is identical with that of the Greeks. One may easily think of examples in the work of Thomas Hardy, Joseph Conrad, and others. The trend has been toward pessimism as an inscrutable destiny has replaced a set of scrutable, jealous, all-too-human deities in the Olympian pantheon.

With Edgar Allan Poe the attempt was begun—indeed, was successfully made, for the time being, at least—to replace the divine with a human agency. Although the Greek drama had perished, all through the Middle Ages and afterward the effort had kept up to preserve the essence of miracle as an invaluable element in human drama. There were both miracles and miracle plays. In place of the Greek deus ex machina, “the god from the machine” with his interventions in human affairs, the world had its Francis of Assisi and its Joan of France. But for whatever reason the divine agency was gradually discredited, the force called Providence or destiny came increasingly to be ignored, and even so great a dramatist-poet as Shakespeare, unable or unwilling to open the heavens to defeat Shylock, could only open a lawbook instead.

What men do not feel as a force in their lives cannot safely be invoked in an appeal to their feelings, and Poe, a genius, knew it. In some of his stories he used in place of the Greek deus ex machina the vaguely supernatural, impressive because vague. In other stories he took the human intelligence, sharpened it, and in the person of Monsieur Dupin made it serve his purpose. M. Dupin, not being a god, could not be omniscient; as the next best thing, Poe made his detective omniscient after the event. If the emotional effect of a Dupin remorselessly exposing the criminal is not as ennobling as retributive justice administered by a god from Olympus, or wrought by Christian miracle, the fault is not Poe’s. It is we who limit the terms of an appeal.

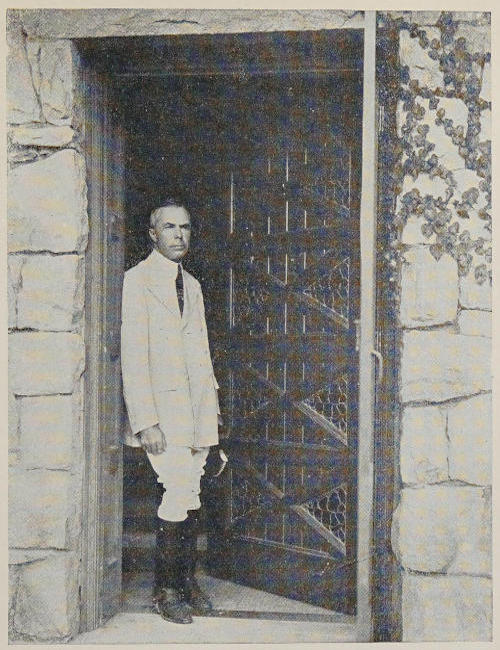

MELVILLE DAVISSON POST

Copyright by The Amon Studio, Clarksburg, W. Va.

Mr. Post has himself commented on the flood of detective stories that followed Poe’s “until the stomach of the reader failed.” Disregarding merely imitative work, let us have a look at such substitutes as have been managed for divinity and fate. We commonly call one type of story a detective story simply because the solution of the mystery is assigned to some one person. He may be amateur or professional; from the standpoint of fictional plausibility he had, in most cases, better be a professional. Poe had his M. Dupin, Gaboriau, his M. Lecoq; Conan Doyle, his Sherlock Holmes. Mr. Post has Abner, his M. Jonquelle, prefect of police of Paris; his Sir Henry Marquis of Scotland Yard; his Captain Walker, chief of the United States Secret Service. If we are looking for Mr. Post’s difference from Poe and others we shall not find it here. The use of a detective is not inevitable; when there is none we call the tale a mystery story. The method of telling is not fixed; and it is doubtful if anyone will surpass the extreme ingenuity and plausibility of Wilkie Collins in a book like The Moonstone, where successive contributed accounts by the actors unfold the mystery at last. One of the few American writers whose economy of words suggests a comparison with Mr. Post was O. Henry. And O. Henry was also a believer in plots, even if the plot consisted, as sometimes it did, in little more than a few minutes of mystification.

Poe had replaced the god from the machine with the man from the detective bureau, but further progress seemed for some time to be blocked. All that anyone was able to do was to produce a crime and then solve it, to build up a mystery and then explain it. This inevitably caused repetition. The weakness was so marked that many writers tried to withhold the solution or explanation until the very end, even at the cost of making it confused, hurried, improbable. Even so, no real quality of drama characterized the period between the crime at the commencement and the disclosure at the finish of the tale. I do not know who was the first to discover that the way to achieve drama was to have the crime going on, to make the tale a race between the detective and the criminal. The method can, however, be very well observed in Mary Roberts Rinehart’s first novel, The Circular Staircase (1908); and of course it is somewhat implied in the operations of Count Fosco in Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White, many years earlier. But this discovery constituted the only technical advance of any importance since Poe. As a noticeable refinement upon this discovery Melville Davisson Post has invented the type of mystery or detective-mystery tale in which the mysteriousness and the solution are developed together. Not suitable for the novel, which must have action, this formula of Mr. Post’s is admirable for the short story, in which there is no room for a race with crime but only for a few moments of breathlessness before a dénouement.

This refinement of Mr. Post’s whereby repetition is avoided, the development of the mystery and its solution side by side, is usually hailed as his greatest achievement. I happen to think that he has in certain of his tales achieved something very much greater. It seems to me that in some of his work Mr. Post has put the deus ex machina back in place, has by a little lifted the mere detective story to the dignity of something like the old Greek tragedy, and in so doing has at least partially restored to the people the purge of pity and the cleansing of a reverent terror.

iv

For whatever tribute one may pay him on the technical side, and every book of his increases the tribute that is his due, the thing that has remained unsaid is his use of plot for ennobling the heart and mind of the reader. He is right, of course, when he says that the primary business of the writer must be to entertain; but more rightly right when he adds that it is possible to do the something more in a work which may aspire to be called a work of art. Anna Katharine Green once wrote: “Crime must touch our imagination by showing people like ourselves but incredibly transformed by some overwhelming motive.” The author of The Leavenworth Case and all those other novels which have entertained their hundreds of thousands, despite appalling technical shortcomings which she never ceased to struggle with but was never able to overcome, was one of the terribly few to command our respect and our admiration in this crucial affair. She was one of the few with whom plot was never anything but a means to an end, and that end, the highest. Of others, it is easy to think at once of O. Henry; it is in this that I would compare him with Mr. Post, and not in any lesser detail such as the power to tell a story with the fewest possible words. All the emphasis that has been put on short story construction in America, all the trumpeting that has proclaimed American writers as the masters of the short story on the technical side will ultimately go for nothing if the fact is lost sight of that a short story is a cup to be brimmed with feeling. And as to the feelings poured into these slender chalices, by their effects shall ye know them.

There is a curious parallel between Mr. Post and another contemporary American writer, Arthur Train. Both began as lawyers, and both showed unusual ability in the practice of the law. Both are the authors of books in which the underlying attitude toward the law is one of that peculiar disdain which, perhaps, only an experienced lawyer can feel. Mr. Train’s stories of Ephraim Tutt display an indignation that is hot enough under their surface of weathered philosophy and levity and spirit of farce. But as long ago as 1896 Mr. Post had published The Strange Schemes of Randolph Mason, his first book of all and one that must detain us a moment.

His career up to that time may be dealt with briefly. Born in Harrison County, West Virginia, 19 April 1871, the son of Ira Carper Post and Florence May Davisson Post, he was graduated (A.B.) from West Virginia University in 1891 and received his LL.B. from the same institution the year following. He was very shortly admitted to the bar of the Supreme Court of West Virginia, of the United States Circuit Court of Appeals, and of the Supreme Court of the United States. He served as a Presidential elector and secretary of the Electoral College in 1892. A young man not yet twenty-five, he conceived that “the high ground of the field of crime has not been explored; it has not even been entered. The book stalls have been filled to weariness with tales based upon plans whereby the detective or ferreting power of the State might be baffled. But, prodigious marvel! No writer has attempted to construct tales based upon plans whereby the punishing power of the State might be baffled.” And he reflected that the true drama would lie in a duel with the law. He thereupon created the figure of Randolph Mason, a skilled, unscrupulous lawyer who uses the law to defeat the ends of justice. Of these stories the masterpiece is probably “The Corpus Delicti.” Well-constructed, powerful, immensely entertaining, surely these dramas are of the essence of tragedy, surely they replace Poe’s detective with somebody far more nearly approaching the Greek god from the machine. In considering the effects of these remarkable tales we can hardly lose sight of their moral purge of pity and terror, their sense of the law man makes as a web which man may slip through or break or brush aside. Why, a true god from the machine, Mr. Post implies, is not necessary to us; we can destroy ourselves; heaven has only to leave us alone. This, in its turn, produces the much stronger secondary effect: the cry for a true god to order and reward and punish us.

Uncle Abner (1918) has been well contrasted with The Strange Schemes of Randolph Mason. “He has demonstrated that wrong may triumph over man-made laws, which are imperfect after all the centuries; but that right must win under the timeless Providence of God.”[10] In Uncle Abner the deus ex machina is fully restored. When it was known how Doomdorf had died, “Randolph made a great gesture, with his arm extended. ‘It is a world,’ he said, ‘filled with the mysterious joinder of accident!’ ‘It is a world,’ replied Abner, ‘filled with the mysterious justice of God!’”

v

Mr. Post married, in 1903, Ann Bloomfield Gamble, of Roanoke, Virginia. Mrs. Post died in 1919. The political career which seemed possibly to be opening before him in his twenties has been neglected for one more fascinating as an author; although he has served as a member of the board of regents of State Normal schools, as chairman of the Democratic Congressional Committee for West Virginia in 1898, and as a member of the advisory committee of the National Economic League on the question of efficiency in the administration of justice (1914-15). He lives at The Chalet, Lost Creek, R. F. D. 2, West Virginia, rides horseback and enjoys the company of his dog, and reads the classics. He is the author of other books besides Uncle Abner which reveal his love for the West Virginia countryside and his power to make his stories take root and grow in that setting. Of his Dwellers in the Hills (1901) Blanche Colton Williams says, in Our Short Story Writers: “To read it is to ride in memory along a country road bordered by sedge and ragweed; to note the hickories trembling in their yellow leaves; to hear the partridges’ call, the woodpecker’s tap, and the ‘golden belted bee booming past’; to cross the stream fringed with bulrushes; to hear men’s voices ‘reaching half a mile to the grazing steers on the sodded knobs’; to meet a neighbor’s boy astride a bag of corn, on his way to the grist mill; to stop at the blacksmith’s, there to watch the forging of a horseshoe; or at the wagoner’s to assist in the making of a wheel; to taste sweet corn pone and the striped bacon, and to roast potatoes in the ashes....”

With the exchange of West Virginia for Kentucky, this is also the background and the mood of The Mountain School-Teacher (1922), but this short novel is an allegory of the life of Christ. A young schoolteacher appears in a mountain village. We first see him striding up a trail on the mountain, helping a little boy who is having trouble with an ox laden with a bag of corn. In the village the schoolteacher finds men and women of varied character. Some welcome him, and they are for the most part the poor and lowly; some regard him with suspicion and hate. The action parallels the life of Christ and is lived among people who are, despite nineteen centuries, singularly like the people of Christ’s time. In the end comes the trial of the schoolteacher on trumped-up charges. “If He came again,” the author seems to say, “it would happen as before.”

Such fiction does not come from a man who is primarily interested in railroads and coal, education and politics, nor from one whose final interest is to provide entertaining fiction.

vi

In recent books Mr. Post has allowed his fiction to follow him on his travels about the earth. The Mystery at the Blue Villa (1919) has settings in Paris, Nice, Cairo, Ostend, London, New York and Washington; the war of 1914-18 is used with discretion as an occasional background. Mr. Poe’s mysticism can be quickly perceived in certain stories; the tragic quality is ascendant in such tales as “The Stolen Life” and “The Baron Starkheim”; and humor is not absent from “Lord Winton’s Adventure” and “The Witch of Lecca.” A story of retributive justice will be found in “The New Administration.” The scenes of most of the episodes in The Sleuth of St. James’s Square (1920) are in America; the central figure about whom all the cases turn is Sir Henry Marquis, chief of the investigation department of Scotland Yard. The material is extremely colorful—from all over the world, in fact. Monsieur Jonguelle, Prefect of Police of Paris (1923) has the same characteristics with the difference of the central figure and with various settings. The reader will observe in these books that the narrative standpoint is altered from story to story; to take Monsieur Jonquelle, some of the tales are related by the chief character, some by a third person, some by the author. The reason for the selection inheres in each affair and is worth some contemplation as you go on. Walker of the Secret Service (1924) is pivoted upon a character who appears in “The Reward” in The Sleuth of St. James’s Square.

This new book of Mr. Post’s is a brilliant example of his technical skill throughout; it has also a special interest in the fact that the first six chapters are really a compressed novel. Walker, of the U. S. Secret Service, is introduced as a mere boy of vigorous physique who falls under the influence of two expert train robbers. The several exploits he had a share in are related with a steady crescendo of interest. At the end of the sixth chapter we have a clear picture of the fate of the two chiefs he served. The peculiar circumstances in which young Walker was taken into the Secret Service are shown; and the rest of the book records some of the famous cases he figured in. The motivation is that of Uncle Abner. “‘Crime always fails. There never was any man able to get away with it.... Sooner or later something turns up against which he is wholly unable to protect himself ... as though there were a power in the universe determined on the maintenance of justice.’”

Two of the most striking stories, “The Expert Detective” and “The ‘Mysterious Stranger’ Defense,” are developed from courtroom scenes—indeed, “The Expert Detective” is a single cross-examination of a witness. Probably this tale and one called “The Inspiration” must be added to the shorter roll of Mr. Post’s finest work, along with “The Corpus Delicti” and “The Doomdorf Mystery.”

The general method has been said, correctly, to combine the ratiocination of Poe’s stories with the dramatic method of the best French tellers of tales. The details of technique will bear and repay the closest scrutiny. But in certain stories Melville Davisson Post has put his high skill to a larger use than skill can accomplish; for those of his accomplishments an endowment and not an acquisition was requisite. When one says that of the relatively few American writers with that endowment in mind and heart he was able to bring to the enterprise in hand a skill greater than any of the others, one has indeed said all.

BOOKS BY MELVILLE DAVISSON POST

| 1896 | The Strange Schemes of Randolph Mason |

| 1897 | The Man of Last Resort |

| 1901 | Dwellers in the Hills |

| 1909 | The Corrector of Destinies |

| 1910 | The Gilded Chair |

| 1912 | The Nameless Thing |

| 1918 | Uncle Abner, Master of Mysteries |

| 1919 | The Mystery at the Blue Villa |

| 1920 | The Sleuth of St. James’s Square |

| 1922 | The Mountain School-Teacher |

| 1923 | Monsieur Jonquelle, Prefect of Police of Paris |

| 1924 | Walker of the Secret Service |

SOURCES ON MELVILLE DAVISSON POST

Mr. Post’s own two articles on the short story are of the highest value, not only to an understanding of his method, but as a contribution to the theory of literary structure—a contribution, unlike most, allied to and realized in practice.

His first article appeared under the title, “The Blight,” in the Saturday Evening Post for 26 December 1914. A shorter article on “The Mystery Story” appeared in the same magazine, 27 February 1915.

In April, 1924, while in New York for a short time Mr. Post dictated the following notes which amplify a little his written articles:

“The modern plan for the mystery or detective story can no longer follow the old formula invented by Poe and adopted by Gaboriau, Conan Doyle, etc. All life has grown quicker, the mind of the reader acts more quickly, our civilization is impatient at delays. In literature, and especially literature of this type, the reader will not wait for explanations. All explanations must be given to him in advance of the solution of the mystery.

“It became apparent upon a very careful study of the mystery story that something must be done to eliminate the obvious and to get rid of the delay in action and the detailed and tiresome explanation in the closing part. It occurred to me that these defects could be eliminated by folding together the arms of the Poe formula. Instead of giving the reader the mystery and then going over the same ground with the solution, the mystery and its solution might be given together. The developing of the mystery and the development toward the solution would go forward side by side; and when all the details of the mystery were uncovered the solution also would be uncovered and the end of the story arrived at. This is the plan which I followed in my later mystery-detective stories—the Uncle Abner series, Monsieur Jonquelle, and Walker of the Secret Service. This new formula, as will at once be seen, very markedly increases the rapidity of action in a story, holds the reader’s interest throughout, and eliminates any impression of moving at any time over ground previously covered.

“It requires a greater care and more careful technique, for every explanation which the reader must receive in order to understand either the mystery or the solution must be slipped into the story as it proceeds without any delay in its action. There can be no pause for explanation. Each explanation must be a natural sequence and a part of the action and movement. The reader must never be conscious that he is being delayed for an explanation, and the elements of explanation must be so subtly suggested that one receives them as he receives the details of a landscape in an adventure scene, without being conscious of it.

“In undertaking to build up a story on this modern formula, one must first have a germinal or inciting incident upon which the whole story may turn as upon a hinge. Out of this controlling incident, the writer must develop both the mystery and its solution and must present them side by side to the reader in the direct movement of the story to the end. When the mystery is finally explained, the story is ended. There can be no further word or paragraph; there can be no added explanation. If a sufficient explanation has not preceded this point, the story has failed. If the reader has been compelled to pause at any point in the story long enough to realize that he is receiving an explanation, the story has failed.

“But it will not be enough if the writer of the mystery-detective story is able cleverly to work out his story according to this formula. He must be able to give this type of story the same literary distinction that can be given to any type of story. To do this he has only to realize a few of the primary rules of all literary structure. He must remember that everything, every form of character, has a certain dignity. This dignity the writer must realize and respect. Flaubert told Maupassant that in order to be original he had only to look at the thing which he wished to describe long enough and with such care that he saw in it something which no one had seen in it before. That rule ought to be amended to require the writer to look at every character and every situation long enough and with sufficient care to realize the dignity in it—that element of distinction which it invariably possesses in some direction—and when he has grasped that, to respect and convey it in his story.