Brenda's Ward

Helen Leah Reed

Brenda's Ward

A Sequel to "Amy in Acadia"

By Helen Leah Reed

Author of "The Brenda Books," "Irma and Nap," "Amy in Acadia," etc.

Illustrated from Drawings by

Frank T. Merrill

Boston

Little, Brown, and Company

1906

Copyright, 1906,

By Little, Brown, and Company.

All rights reserved

Published October, 1906

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U.S.A.

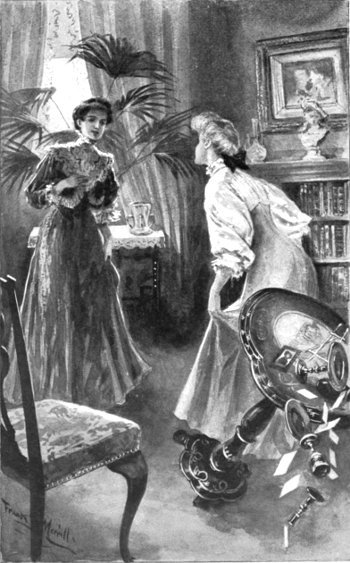

"As Martine courtesied her thanks for this compliment, she backed gracefully."

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I. A New Home

CHAPTER II. A Strange Meeting

CHAPTER III. Priscilla's Pride

CHAPTER IV. Changes

CHAPTER V. Another Parting

CHAPTER VI. Angelina's Coup

CHAPTER VII. A Drop of Ink

CHAPTER VIII. A Prize Winner

CHAPTER IX. Word from Brenda

CHAPTER X. The Recital

CHAPTER XI. Martine's Altruism

CHAPTER XII. Puzzles

CHAPTER XIII. At Plymouth

CHAPTER XIV. Tales and Relics

CHAPTER XV. Troubles

CHAPTER XVI. The Missing Trunk

CHAPTER XVII. Class Day

CHAPTER XVIII. At York

CHAPTER XIX. Sight-Seeing

CHAPTER XX. The Isles of Shoals

CHAPTER XXI. Variety

CHAPTER XXII. Excitement

CHAPTER XXIII. Quiet Life

CHAPTER XXIV. Portsmouth and Afterward

CHAPTER XXV. The Summer's End

HELEN LEAH REED'S "BRENDA" BOOKS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

"As Martine courtesied her thanks for this compliment, she backed gracefully"

"'The real Memorial is here,' said Elinor, reverently, passing from one tablet to another"

"'This little scarf—it is Roman, too,—is just the thing for Julius Cæsar'"

"Aunt Nabby seemed to be making little dolls of clay"

"The old captain proved very talkative"

"While Martine was sketching, Clare fluttered about"

Brenda's Ward

CHAPTER I

A NEW HOME

"It's simply perfect."

"I thought you would like it, Martine."

"Like it! I should say so, but it isn't 'it,' it's everything,—the room, the house, you, Boston. Really, you don't know how glad I am to be here, Brenda—I mean Mrs. Weston."

"What nonsense!"

"That I should like things?"

"No, that you should call me 'Mrs. Weston.' It's bad enough to be growing old, so don't try to make me feel like a grandmother. Truly, I can't believe that I am a day older than when I was sixteen, and yet when I was sixteen, eighteen seemed the end of everything worth while. I could not imagine myself old, and serious, and—twenty."

Martine smiled at Brenda's emphasis of the last word, and as she smiled she laid her hand on her friend's arm.

"Come," she said, "just look in this mirror. A person who did not know could not tell which is the older, you or I."

"Again, nonsense!"

Yet even as she spoke Brenda could but admit to herself that Martine had an air of dignity suited to one much older than a girl of seventeen. But if she had thought Martine altogether grown up, she quickly changed her opinion, for at this very moment Martine sank on the floor beside her, and as her laughter re-echoed through the rooms Brenda was driven to say:

"My dear, don't talk to me about being grown up. You act precisely like a child of ten. What in the world is the matter?"

"Nothing, oh nothing; that is, almost nothing. Only look and you will laugh too."

Glancing where Martine pointed, Brenda saw something really amusing. Before a pier-glass in the hall a sallow girl with glossy black hair piled high on her head was standing. She wore a pink satin gown that heightened her sallowness. It was cut square in the neck, and her elbow sleeves displayed a pair of skinny arms.

"Who is she?" whispered Martine, recovering her breath.

"Why, that, oh that is Angelina."

Martine, fascinated by the vision in the glass, continued to watch the strange little figure, bowing, gesticulating, turning now to this side now to that, while her lips moved as if she were talking to herself.

"Who is Angelina?" asked Martine.

"Oh, Angelina, don't you know her? She is to help me for a week while Maggie is away taking care of her sick aunt."

"Do you call that 'helping'?" and again Martine pointed toward the pier-glass.

"She did not hear me come in; she thought I would ring," replied Brenda. "She thinks I am still downtown. She was to go to the door and has been waiting to hear me ring."

"Would she go to the door looking like that?"

"Oh, I hope not. She'd probably call through the tube and hurry on a coat, or do something of that kind. Yet no one is ever surprised at Angelina's doings. Let me tell you about her. Years ago Nora and some of the rest of us pulled her little brother Manuel from under the feet of a horse, and in a few days we went to visit the family at the North End. You can't imagine how poor they were. Then we had a club and worked for a bazaar to raise money to get them out into the country."

"Oh, yes, Amy told me something about that, though it all happened before she knew you, I think she said."

"Well, in the end Angelina became my cousin Julia's protégée. She has learned a great deal about housework at the Mansion School, but she is always yearning for something beyond. Lately she has been taking lessons in elocution."

"That's it, then, she's rehearsing now," cried Martine. "Oh, I hope Maggie will stay away longer than you expect. I think we might have great sport with Angelina."

"My dear," remonstrated Brenda, "remember that for the present you are my ward. I can't have you trifling with Angelina, although she can be very funny."

The sound of voices had at last penetrated Angelina's ears, and she fled to her room.

"Oh, my," she thought, "I wonder if Mrs. Weston saw me?" In her secret heart Angelina hoped that she had been observed.

"And Miss Martine, she's almost as stylish as Mrs. Weston. I wonder what she thought of this dress—gown," she added, correcting herself. "I almost wish I'd been saying that soliloquy out loud. Then I could have asked them if they thought I used just the right inflections and gestures. Perhaps Miss Brenda would let me recite it all to her some time. She's more sympathetic than Miss Julia was. Now I know if I should ask Miss Julia she'd say I mustn't give that recital, and I'm sure she wouldn't approve of this gown. But Miss Brenda, why I shouldn't wonder if she'd go to it herself, and Miss Martine, I've heard how she spends money like water, and she'll probably buy a lot of tickets."

As Angelina fled to her room Martine, rising from the floor, sat down on a divan beside Brenda.

"If you wish to please me, do find another place for Maggie and keep Angelina. She'll be so entertaining, and poor Maggie always looks half ready to cry."

"Oh, I couldn't part with Maggie, and more than a week of Angelina would be too much even for you."

"Well, I will tell you at the end of this week. I am going to work so hard at school that I ought to have as much amusement as possible at home. Still I know I am going to be perfectly happy with you this winter, although I can remember the time when I should just have hated to spend a winter in Boston. Even now if it wasn't for you—"

"But you had decided to spend the winter here before you ran across me."

"No, my dear Mrs. Weston, my parents had decided that a year or two of Boston school would be the making of me. They had heard, as you know, of a dragon who had a boarding-house on the hill, who would look after me within an inch of my life. Wasn't it strange, though, that she should have been taken ill this autumn? I suppose you wouldn't let me say 'providential.'"

"Certainly not! She was so ill that she had to go South for the winter."

"Then that is providential for her. How much better the South must be for her than this bleak Boston. Besides, if she had been able to continue her home for helpless Western schoolgirls, I should not have had the delight of sharing your charming apartment."

"Nor should I have had the pleasure of the company of a charming ward."

As Martine courtesied her thanks for this compliment, she backed gracefully, and neither she nor Brenda realized that she was approaching too near a table of bric-à-brac, until it toppled over with a crash.

"Oh what have I done! No wedding presents smashed, I hope." There was a touch of dismay in Martine's voice.

"Not a thing that could break." Brenda's smile was reassuring. "Silver or brass, everyone of them. That's one thing I have already learned, not to have breakable things, if one values them, within anyone's reach. It's awfully disagreeable to have to blame anyone for what you could have prevented by a little care, and I never can let anybody replace what she has broken. Maggie is rather a breaker, and so my china and glass ornaments I set on high shelves."

The noise of the falling table brought Angelina upon the scene. She had made what Martine called a "lightning change," and appeared in a dark gown and spotless collar and cuffs.

"Why, are you in?" she said innocently, as she entered the room. "I didn't know but what it might be a burglar or something—" She looked from one to the other anxiously, and then catching sight of the overturned table, began to busy herself picking up the scattered ornaments.

"Oh, dear," sighed Brenda, "will Angelina ever learn to be perfectly honest?" But her only words alone were. "Yes, we have been in some time; I thought you might have heard us." The implied reproof silenced Angelina, and soon the three separated without a word having been said about the private rehearsal.

That the volatile Brenda Weston should undertake the charge of Martine Stratford for the winter at first surprised many of their friends, and yet this had come about in a perfectly natural way. When Martine returned from her summer with Amy in Acadia, her mother, who met her in Boston, was so much better that it seemed almost possible for her to spend the winter at home. But at last her physician prescribed a few months of travel, and as Martina's school work had already been unduly interrupted, it was thought wiser for her to carry out the plans already more than half formed that she should stay in Boston to attend Miss Crawdon's school. It was therefore a disappointment to Mrs. Stratford just before school opened to hear that Mrs. Montgomery, Martine's so-called "dragon," was ill. For several years the latter had been in the habit of having a few girls from a distance board with her while they attended school in Boston. When Mrs. Montgomery could not take her, Martine's parents thought that they must altogether give up the Boston plan. Mrs. Blair, a cousin of Martine's mother, with whom she had stayed in the spring, was now in Europe. Mrs. Redmond, in whose charge they would have liked to put Martine, had engaged a boarding-place in Wellesley, to be near her daughter in college; and had there been no other reason against Martine's living in Wellesley also, her parents objected to her going back and forth daily on the trains. The case seemed hopeless for Martine's staying in Boston until Brenda Weston came to the rescue.

Brenda was for a few days at the large hotel overlooking the park, where also Mr. and Mrs. Stratford and Martine were staying. Martine had heard much of Brenda, though she had never met her until one afternoon when Amy came to call. Delighted to have the opportunity, she immediately introduced Brenda to her Chicago friends. This happened to be the very day when Martine was feeling most discouraged regarding her school plans. For although the young girl sometimes scoffed at Boston, she really wished to spend the winter there. Her summer's companionship with Amy and Priscilla had increased her ambition, and she was anxious to study at Miss Crawdon's.

Very naturally, then, she confided her troubles to Brenda. Brenda sympathized with her, but made no suggestion until she had talked the matter over with her own family and with Martine's mother. When Mrs. Stratford told Martine that Brenda had offered to take her under her wing for the winter, Martine, overjoyed, rushed to Brenda's room to express her thanks.

"I can't tell you how delighted I am at the thought of living with you in that dear little flat. It will be much more fun than anything else I could possibly do."

Brenda looked at her keenly, shaking her head in mock reproof.

"You are not coming to me just for fun. Your mother says that this must be a very serious year for you, that you did not do so very well in school last year, and that—"

"There, there, Brenda,—I mean Mrs. Weston, dear,—I can be terribly serious. You will see for yourself. But still you want me to have a little fun, just a little—"

"Oh, yes; I am not a regular dragon, but I understand the importance of work."

With a sudden movement Martine, who had been standing behind Brenda, threw her arms over Brenda's head, placed her hands over Brenda's mouth, thus silencing her for the moment.

"Now listen, listen," she cried; "listen, please! Of course I am only too glad to be your ward, and I will be as good as good can be. I would promise anything rather than go to boarding-school, or live with Mrs. Blair, or board in a house full of girls. Lucian hopes I'll stay in Boston because he is a little lonely sometimes at college, and I wish to stay with you, and you are so sweet to give me the chance that I really won't make any trouble for you."

So it was settled, and Mr. and Mrs. Stratford went home, quite satisfied to leave Martine in Brenda's care. They would have been better pleased had Mrs. Redmond been able to take complete charge of their daughter; but as it was, Mrs. Redmond promised to have Martine constantly in mind and to help her when any emergency arose.

It was Martine's one regret, when she took up her abode with Brenda, that she had not become Brenda's ward early enough in the season to help her furnish.

"It must have been such fun," she said one day soon after her arrival, "to shop for all these pretty things, and decide on wallpapers and rugs, and fit them into their little corners and nooks."

"You know I didn't have to go shopping for all my belongings; you have no idea what quantities of things were given me."

"Oh, I can imagine, just by looking around. Wedding presents are so fascinating."

"But still," continued Brenda, "there were certain things I had to buy, chairs and tables, for example, and it was hard sometimes to decide between Mission styles and mahogany, and whether the bedstead should be brass or painted iron for the smaller rooms; and then the kitchen furnishings were puzzling. Of course I'm not perfectly satisfied with everything, but, on the whole, we must be contented until we have a house."

"Oh, how can you speak of a house! This is ever so much better. It's the prettiest flat I ever saw; don't you just love to be up here in the top? You can see over everything, even to the river, and down the avenue and up the avenue; it's more like Paris than anything I've seen since I was in Europe."

"I do enjoy the view," replied Brenda. "I should hate to be shut in in a narrow street. I don't like it here quite as well as in our old house on the water side of Beacon street, where my room had such a broad outlook."

"You must have hated to leave home."

"In a way I did, but though mamma tried to persuade me to stay with her this winter, I felt that I just must begin to keep house myself."

"You ought to be very happy that you are so near your mother." Martine spoke wistfully; although she wouldn't have admitted it for the world, she was beginning to be homesick. Chicago seemed altogether too far away.

"It is pleasant," replied Brenda, "to be able to run in and out there when I please. Besides, my sister and her children are there, and I am awfully fond of the little girls."

"Naturally. But that reminds me, though there isn't any real connection with what we've been talking about, you haven't shown me your kitchen. Can't we go out there now?"

"Why, yes,"—then Brenda's face clouded,—"if the cook—"

"Oh, Brenda Weston! You are afraid of the cook."

Brenda colored. "Not afraid; only you know cooks are so queer, and of course dinners have to be just so, and she's apt to spoil things if anything annoys her. But this is her afternoon out."

"Then we can go and look through everything," and Martine thereupon followed Brenda through the long narrow hall to the little kitchen at the very end of the suite.

"You see," explained Brenda, as they entered the cook's domain, "though this is not an old house, the kitchen needed some improvements that I learned are necessary when I lived at the Mansion. It's astonishing how many things men forget when they build houses. Now, out here, there was an old-fashioned closed-in wooden sink, but I had it replaced with this open one at our expense, and this tiling put all around the walls, and here, this was my idea and this," and one by one she pointed out many little things that might have escaped Martine's notice.

"I learned so much," continued Brenda, "that year at the Mansion School. You see a year ago last spring I was very low-spirited. Everything seemed so gloomy after the war began, so I went for a while to help Julia with her girls; and hardly anyone, hardly Julia herself, realized that I was learning. But I was, and somehow things that I didn't know I had noticed sank into my mind, and when we began to get this apartment ready, I was really practical; even my mother said so. Arthur was pleased, and my sister Anna was perfectly astonished. You know she has lived mostly in studios, or in houses where someone else did the planning, and this year at home with mother she has no responsibility, so she can't understand how I know so much about housekeeping."

"It is strange, it seems strange to me," responded Martine. "No one would ever expect you to know a thing."

"Why not? Do I appear a perfect ignoramus?" There was indignation in Brenda's tone.

"Oh, no, of course not; only kitchens are so different, so—well, I shouldn't expect you to know about kitchen work."

"Then, I confess, there's one thing I don't understand very well. I really cannot cook. Sometimes I think it's on account of the cooking class we used to have; it was too much like work, and so I didn't try to remember what I was taught. That's why I'm afraid of the cook, for if she should leave suddenly, I don't know what I should do."

"I know what I'd do," responded Martine, quickly. "I'd go to a restaurant; it's ever so much more fun than dining at home. Why, when I was visiting my cousin in New York, we went somewhere nearly every evening. Of course there isn't a Sherry's or a Waldorf-Astoria here—"

"Oh, I don't want to dine at restaurants when I've a house of my own. Besides, I'm going to learn—look!" and Brenda opened the door of a small closet. "These are all electric things," and she pointed to a row of silver kettles and chafing-dishes. "We have two plugs in the dining-room wall and can cook almost anything without going into the kitchen. But come, I've something to show you in my own room now." As they turned away Martine exclaimed, "If you have a good receipe book, with all those shiny saucepans, I'm sure you needn't care whether you have a cook or not."

"I'm not so sure," responded Brenda, "and I can't help being just a little afraid."

"Pshaw! How absurd!—as if you could really be afraid of anything," retorted Martine with a smile.

Now, interesting though Martine found her life under Brenda's roof, she soon realized that her winter was not to be one wholly of pleasure. Her studies had been carried on so irregularly for a year or two that she now perceived that she must settle down to regular work. School had been in session a week or two before she returned to Miss Crawdon's; this fact was not altogether in her favor, and she found herself a little behind the girls in her class. But Martine was resolute, and when she once set herself at a task in genuine earnest, she was likely to go ahead with a will. So, for the first month she studied diligently; it was to her advantage that she had not many Boston acquaintances.

Brenda, in her new position of guide and philosopher as well as friend, gave Martine much good advice. One day in a serious mood she expressed the hope that Martine would not think of ending her studies at Miss Crawdon's school.

"It's astonishing," she said, "how many girls are beginning to fit for college, though when I was in school many of us thought my cousin Julia queer because she studied Greek and wished to go to Radcliffe; yet really she wasn't queer at all, only rather more interesting than most people."

"I should like so much to see her, everyone seems so fond of her," responded Martine. "When will she come back from Europe?"

"Not before summer, I think. She worked so hard at the Mansion School last year that we all hope she'll get all she can out of this journey. She's studying, of course, for she never can be perfectly idle; but I am glad to say that she has gone back to her music, for that is the thing she has the most talent for."

"Oh, dear," sighed Martine, "how delightful it must be to know that you have a talent for anything. It seems to me sometimes that I haven't a particle of talent. I can do several things passably well, but no one thing better than another. Mother thinks that the Boston air is going to develop some special talent of mine, but which or what, nobody knows. For my own part, as I said before, I am sure that I have no talent."

"Don't be so severe toward yourself," expostulated Brenda. "I am sure of one thing—you have a talent for being pleasant and amusing."

"I'm not quite sure that that is exactly a compliment."

"But, really, I mean it to be one."

CHAPTER II

A STRANGE MEETING

One Saturday morning after a rainy Friday, Martine looked out the window.

"How refreshing to have a fine day again. Really, when it poured yesterday I thought it would rain forever, and I had such a funny adventure, Brenda Weston, that if you hadn't been out when I came home I should have told you on the spot. Adventures are like buckwheat cakes, so much better when they are fresh from the griddle, and this was a kind of frying-pan affair."

"I am afraid I don't understand. What was it?"

"Something that happened after the Rehearsal. I slipped away from Priscilla and her aunt and there was a great crowd going down the steps yesterday, so that of course I got separated from Priscilla and her aunt."

"It seems to me that's a way you have," Brenda tried to speak severely.

"Oh, yes," sighed Martine, "Mrs. Tilworth is quite resigned now. Generally I separate myself from her only about every other week, but yesterday I wanted some soda water, and I knew she would never condescend to go into a drug shop or let Priscilla go with me. However, when I was once in the street the rain was falling in such torrents that I made a beeline for a Crosstown car that I saw coming. I had had some trouble in getting away from Mrs. Tilworth, for she kept not only her eagle eye, but her arm on me as long as she could; she meant to bring me home in a cab, but after all I managed to wriggle away. I don't know why I thought I ought to run for my car, but I did, and so did another girl, only the trouble was, that she was coming from the opposite direction. Of course you can see what happened. I didn't mean to knock her down, for she was shorter than I and we were both furious."

"Because she was shorter than you?"

"Oh, I don't see now why we were both so mad, only she knocked my hat off, that one with the light blue feathers, and it went sailing down the asphalt, and my umbrella jabbed into her face. 'You're terribly clumsy; I should think you might see what you're doing. You might have put my eye out,' I heard her say in the savagest kind of a tone. Just then I caught sight of my hat, and all I could do was to laugh and laugh, and she thought I was laughing at her, and turned her back on me in a regular frigid Boston way, holding her handkerchief to her eye."

"How could so much happen while two people were getting on a car?"

"Getting on a car! Naturally we missed the car. It didn't wait for us to settle matters. I suppose that was partly what made her so cross. But I wish you could have seen my hat when finally I picked it up."

"I'm glad I didn't, if it was ruined. I have some responsibility for your clothes. No wonder Mrs. Tilworth tries to keep her eye on you!"

"She has to try pretty hard, I can assure you," retorted Martine.

"You should take things more seriously," rejoined Brenda. "In future please come home at least as far as Copley Square with her and Priscilla, but now—yes, now let us go in and look at the table." And with her hand in Brenda's arm, Martine led the way to the dining-room. The sight that met her eye there was indeed well worth seeing. The polished surface of the round mahogany table shone like a mirror. Covers were laid for nine and the centrepiece and doilies were embroidered in yellow. In a tall green glass in the middle were some large yellow chrysanthemums. The bonbons were in little gilded baskets and the china had yellow blossoms on a white ground.

With housewifely pride Brenda adjusted the blinds. "Yes," she said, "I think that everything will go just as it should. Elinor Naylor, you see, is a sister of one of Arthur's best college friends. I should like to have asked her to dine, but the cousin she is staying with has an engagement for her this evening, and as Arthur will be away next week, a luncheon was the best thing I could manage."

"Oh, it's just the thing," cried Martine; "dinners are so stiff. With the boys coming in to take us out to Cambridge, a luncheon will be far jollier than any dinner."

"I hope so," replied Brenda, "and I wonder what this Elinor Naylor is like. She was out when I called, but she writes a beautiful note, and from what I have heard, I imagine that she is rather stately and elegant. But dear me, it's nearly twelve, and with luncheon at one we shall really have to hurry." So with a few last touches to the table Brenda and Martine went to their rooms, and long before one, Brenda, with some trepidation, was waiting in the library for the arrival of her special guest. The Harvard boys, however, were the first to arrive—Fritz Tomkins, and Martine's brother Lucian, and Robert Pringle, Lucian's classmate. Next came Priscilla and Amy, the former somewhat abashed at hearing the laughter from the little library, and wondering if she could be late, until Amy reassured her. Priscilla bore some good-natured chaffing from her host, who seeing her glance at her watch, could not forbear teasing her.

"Yes," he said, "I can read the workings of a guilty conscience. Here we've been waiting for you this long time. The goose is burning up in the oven—"

"There isn't any goose in the house, Arthur, except you," protested Brenda.

"I am so sorry," began Priscilla, apologetically. "It was because Amy—"

"Don't throw the blame on another," protested Mr. Weston, solemnly.

"I don't mean to blame her. We both thought it was earlier, and besides," fortified by a glance at her watch, Priscilla spoke with more decision, "my watch says 'a quarter before one.'"

"That's what our clock says too," interposed Brenda, kindly. "Arthur was only teasing. Our guest, evidently, does not mean to be too early."

"If she's like her brother, she's a punctilious person and will arrive promptly at five minutes before one."

Strange to say, the longer hand had just marked five minutes of one when Angelina announced "Miss Elinor Naylor." A minute or two later the young lady entered the room, and after the other introductions had been made, Martine's turn came last.

As she greeted all the others, Miss Elinor Naylor had extended her hand very cordially, but when Brenda led Martine to her, her arm fell automatically to her side. Martine at the same time reddened deeply, and it was not often that Martine was so perceptibly embarrassed. Each girl, however, said a polite word or two, and in a few moments all went out to the little dining-room.

After they were seated, the conversation at first was not general, and I am afraid that anyone who had overheard the words exchanged between any two speakers might have called what was said rather commonplace. In a short time, however, some question arose regarding a recent Yale victory, and at once Arthur and Fritz plunged into an ardent discussion in which, soon, all took part.

"Oh, of course," said Arthur; "it's more than six to one. I know you are all against me. I can't even depend on Brenda, and so, Miss Naylor, I must turn to you as my one supporter in this controversy."

"You can depend on me," replied the guest; "whatever a Yale man says is bound to be true."

"The real Yale spirit," commented Martine. "I didn't know that girls had it as well as their brothers."

There was an unamiable tinge in Martine's tone that Brenda, too much occupied with things more important, did not notice. The more observant Arthur, however, had seen that Martine and Elinor had had little to say to each other, although they had been placed at table where they could easily have said more.

"You two young things," he said at last, "by which I mean our visitors from Chicago and Philadelphia, look at each other as if you had met before and were afraid to speak until you had found the clew to the previous meeting. Is that the case?"

Elinor was silent, but after a second Martine replied,

"No, not exactly; that is—" Then Martine came to a pause suddenly and answered some question that Robert Pringle, on her right hand, had asked her. Any embarrassment that she or Elinor might have felt was speedily ended by something with which they personally had nothing to do.

Now it happened that although Maggie had returned to her post of duty in Brenda's household, the latter had decided that things would move more smoothly with two waitresses, and so Angelina had been called in to assist at the little luncheon. All would have gone on well had not a spirit of emulation taken possession of the two helpers, so that each seemed anxious to reach Elinor first. Twice, as they entered through the swing door, one almost abreast of the other, although Brenda had previously given them their directions, they both started to serve the special guest with her oysters, and only Brenda's warning glance prevented Maggie's plate from being placed on top of the one that Angelina had already set before Elinor. This incident ruffled the spirits of the two waitresses, and when they entered with their cups of bouillon, each was determined to reach Elinor before the other. The result of their exertions might have been more disastrous. As it was, Elinor did not suffer, though Martine, looking up suddenly, expected to see Maggie's cup splash over Elinor's light gown. Luckily—for Elinor—Maggie lost her nerve soon enough to drop her bouillon cup to the floor, and though the crash of china and the splash of liquid on the polished floor startled all at the table, Elinor escaped a drenching.

Although everyone knew that there had been an accident, everyone tried to look unconcerned. Maggie, crestfallen, gathered up the pieces; Angelina, with her head high, as if such a catastrophe could never occur to her, went back to the kitchen for other cups—and only Martine giggled.

"Your best Dresden," murmured Amy to Brenda. The latter shook her head. Arthur glanced at her approvingly.

"And mistress of herself, though china fall," and at the hackneyed quotation, all smiled. Then the luncheon went on for two courses with only one waitress, for Maggie had betaken herself to her sure refuge, a flood of tears, and she returned only with the salad.

"Now," said Mr. Weston, "since the ice is broken—I mean, the china—you can see how much livelier we are. During the oysters you were altogether too quiet for young people, and I wondered if this was wholly because your host is a Yale man. It's painful to me sometimes to find myself in the midst of a Harvard crowd."

"Oh, we are magnanimous, and since you've become a Bostonian, we can forgive you Yale's recent football victory," replied Fritz.

"Then I can confess that my cheering played a large part in gaining the victory. I try to be as modest as I can about it," responded Arthur Weston.

"Wait till the baseball season comes," interposed Robert Pringle, "and then you'll see another side of Yale."

"I wish we girls could have seen the game," cried Martine. "I can't see why they played it at New Haven; it was the one Saturday of the whole autumn when I had to stay in Boston."

"Why, it was New Haven's turn to have the game; you know Harvard and Yale have them on their own fields every other year," said Elinor, as if explaining something that Martine did not understand.

"Oh, indeed," began Martine, sarcastically; then, remembering that she was to a degree Elinor's hostess, she murmured in an aside to Robert, "As if I did not know that better than she."

"It's strange," continued Elinor, in a placid tone, "that I know so little of Harvard; we generally rush through Boston on our way to Bar Harbor. Once we drove round, one hot summer day in vacation, but I can only remember a Memorial Hall and some queer old brick buildings." Possibly Elinor's adjectives did not please Martine, for the latter spoke up quickly.

"They're not queer, but historic; we think everything of Harvard here in Boston."

"Oh, naturally," replied Elinor, in her most languid tone.

"So say we all of us," cried Robert Pringle, while Amy and Fritz, who had been carrying on an animated discussion, looked up quickly. "What's wrong?" asked Fritz, innocently.

"Nothing, nothing," and Brenda, hastening to change the subject, asked suddenly, "Did you bring your automobile, Lucian?"

"Of course. I only wish I could take you all to Cambridge in it."

"Who's going in which?" asked Amy a little later, as they stood at the door, before which were Lucian's automobile and Robert Pringle's dogcart.

"Oh, the automobile for me!" cried Martine, impulsively.

"Will you go in the automobile?" asked Lucian politely, turning toward Elinor.

"Yes, indeed, I should like to, thank you," replied the guest.

"Priscilla is coming in the dogcart with me," said Mr. Weston.

"Then I think I'll drive with Priscilla," added Martine.

"Such affection!" exclaimed Amy. "To give up the automobile because you prefer Priscilla's company!"

"It isn't that I like Rome more, but Cæsar less," rejoined Martine, garbling her quotation and looking toward the automobile, where Elinor had already taken her seat.

Amy understood, and decided to give Martine a bit of advice at the first opportunity; for the present she and Brenda, with Fritz and Lucian, went in the automobile with Elinor, while Arthur and Robert Pringle accompanied Martine and Priscilla. The automobile speeded out through the Avenue across a corner of Brighton, that Elinor might have a good view of Soldiers Field. The dogcart proceeded over Harvard Bridge, and Martine tried to make Priscilla take a wager as to which vehicle would first reach the College Yard.

When at last, however, they drew up before the Johnston Gate, Lucian and his party were waiting there, having left the automobile at the garage.

"As we're going to explore these unknown regions on foot," said Lucian, "we can't allow you to drive haughtily around. There's a boy, Robert, to take your trap over to the stable. And so," he added, after Martine and Priscilla had alighted, "the elephant now goes round, the band begins to play; in other words, let the procession move in through the great gate. It was given by a Chicago man," he concluded. "That's why I'm proud to have you see it."

After the gate had received its share of admiration, "Here are your 'queer old brick buildings,' Miss Naylor," cried Fritz. "Every brick has a history, but I can't show you the college pump. It was blown up by anarchists, who probably meant to blow up one of the buildings."

"How shocking!" said the sympathetic Elinor.

"That they did not blow up the buildings?"

"Oh, no, but that they should behave so badly. I trust they were punished."

"Oh, they were blown up too."

"Really?"

Although Elinor gazed directly at Fritz, there was no suspicion in her calm blue eye.

"Doesn't she remind you of my cousin, Edith Blair?" whispered Martine to Amy.

"I can't say that they look much alike."

"Oh, Amy, please don't be literal, too. I mean she believes everything Fritz says, and between him and Mr. Weston she'll have a hard time."

"And a strange opinion of Harvard," added Brenda, who had joined the two speakers.

As the majority of the party, including Elinor, were now out of hearing, Brenda thought this a good time to ask Martine to explain her prejudice against Elinor, "who seems a pleasant and dignified girl," she concluded.

"Yes, that's it; she's too dignified for her size, she ought to be bright and jolly and—"

"But remember, please, that she's among strangers. You can't dislike her simply because she's quiet and dignified, so you might as well confess."

"Well, then," replied Martine, "if I must, I must; but you'll understand, when I tell you that she's the girl who knocked my hat off."

Amy looked puzzled and Brenda smiled as she responded, "Oh, the girl whom you tried to knock down with your umbrella. I suppose that is what has made that scratch on her face. No wonder she is on her dignity with you."

"I shouldn't have cared," retorted Martine, "if she hadn't refused to shake hands with me to-day. Surely everyone must have noticed that, and it's she who ought to apologize for destroying my third best hat."

Then, as she recalled the sight of the hat with the pale blue feathers sliding along on the asphalt, Martine laughed heartily, and from that moment, in her mind, all was peace between her and Elinor.

"I didn't mean to get so far ahead," explained Lucian, as the others came up to the spot where he and Fritz were standing with Elinor. "But Miss Naylor is delighted with Holden."

"Yes," murmured Elinor, "it is the cunningest little building! I should like to pick it up and carry it off as a souvenir. It's too bad that it isn't the very oldest of all the buildings now standing."

"No, Massachusetts has that honor, but Holden is the first to take its name from an English benefactor," said Fritz.

"It seems too bad that nothing remains of the original Harvard, but the fire of 1764 swept them all away. Massachusetts is older than that, and so are one or two others now standing. The old buildings are not particularly beautiful," Robert Pringle apologized.

"But they look like New England," interrupted Martine, "so practical and business-like and angular; that's why I like them."

"There must be some interesting stories connected with them," said Elinor, sentimentally.

"Oh, yes, stories, quantities of them. What would you like to hear?" asked Fritz, with an eagerness that showed he was ready to manufacture any tale or legend that Elinor might desire.

"Did the college go on during the Revolution?" asked Elinor. "I know Washington had his headquarters in Cambridge."

"The library was sent up to Andover for safety, and the students to the Concord Reformatory."

"Oh, Fritz," protested Amy, "if you are not careful, Miss Naylor will believe you."

"Why not?" asked Fritz, innocently. "It's history that they were sent to Concord, and why not to the Reformatory? They must have needed it, if they were like some of the present students, and they would have been sent there surely had Concord possessed a reformatory in those benighted years."

Upon this Lucian insisted that Miss Naylor must accept him only as her Harvard guide; otherwise she would get an utterly wrong impression.

"Let me tell you," he began, "about the squirrels. Really, they are of more consequence than most other dwellers in the Yard. They will eat anything, from mushrooms to pâté de foie gras, and although it's rather expensive, we try to give them whatever they demand. The tree trunks here are probably filled with treasures that they have hidden away; some of them even are fond of books, and I heard of one who had an intimate acquaintance with Greek roots. No nuts are too hard for them to crack; they are real philosophers, and here," he cried as he threw some acorns on the grass, "they are so tame one doesn't have even to throw salt on their tails to catch them."

Upon this, with a deft movement, he picked up a bushy-tailed gray squirrel that had been attracted by the bait he had thrown down, and as he held it toward Elinor, "Here," he exclaimed, "if you wish a souvenir of Harvard, is the real thing," and extending his arm, he pressed the little creature's head against Elinor's cheek. Then, to everyone's surprise, Elinor Naylor, the dignified Miss Elinor Naylor of Philadelphia, screamed loudly, and turning her back on Lucian, ran up to Martine, who happened to be nearest her, and laid her head on Martine's arm, crying loudly, "Take it away, take it away, it's just like a big rat."

Lucian, decidedly crestfallen at this little episode, let the squirrel whisk itself away, while he walked up to Elinor to offer his apologies. In his heart he was saying, "Thank heaven that Martine has some nerve," and Martine herself, by a sudden revulsion of feeling, at once became the champion of the girl she had recently been criticising.

Elinor accepted Lucian's apologies very graciously. "I know that I am foolish," she said, "but I never have liked those little creepy animals; they all seem to be like rats and mice, except at a distance."

"You were certainly very thoughtless, Lucian." Martine spoke in a tone of deep reproof, and during the remainder of their walk she had Elinor hanging on her arm.

The suite of rooms occupied by Lucian and Robert Pringle was in a dormitory outside the Yard, in the neighborhood of the old ballground, Jarvis Field. To reach it the party went across the Memorial Delta, past the statue of John Harvard—concerning which the boys had various strange tales to tell—and along a quiet street on which were several other dormitories.

"How delightful! This suite is much more attractive than Joe's rooms at Yale, as I remember them," cried Elinor.

"Yes," sighed Arthur Weston, "Joe and I were not sybarites. We went in for hard work, plain living, and high thinking," and he looked reproachfully toward Lucian and Robert.

"We work too, I can assure you," insisted Robert. "Of course we had to furnish up a little."

"Work! I should say so," added Lucian. "Don't judge us by our surroundings."

"We'll try not to," retorted Martine, "for this tea-table is almost too ladylike for two tall boys like you."

"Oh, when we're alone we never look at the tea-table. We fold it up and keep it in the closet. To-day we brought it out only for you girls," and Lucian bowed profoundly to his guests.

"I think that your belongings are rather frivolous," and Brenda took the little silver tea caddy in her hand.

"Oh, I picked that up in Holland; it's a mere trifle," cried Robert.

"These things are wasted on boys," added Martine, examining the little coffee spoons that lay on the tray.

Amy, walking round the room, gazed critically at the two or three water-color sketches and the fine photographs hanging on the walls, and she thought that the easy-chairs, the broad divan, and all the other handsome belongings were really too elaborate for the rooms of boys under twenty.

"But there's one good thing," she said aloud; "you have plenty of books, Lucian, and you have made an excellent choice in many cases."

"Yes," replied Lucian, "thanks to Fritz, our library has made a good beginning; he took it in hand last spring, and what do you think? Fritz says that if it hadn't been for you, he couldn't have helped us half as well. So, Miss Amy Redmond, when you praise our library, indirectly you praise yourself."

Before their hour in Lucian's room was over, few things in the sitting-room had escaped the scrutiny of the three younger girls. They handled the steins on the mantelpiece, read the certificates of membership in various clubs and athletic societies, and admired the photographs of all, and finally Martine struck up a few chords on the piano, which Lucian and Robert recognizing, accompanied with a jolly college song. At Lucian's request Priscilla made tea, and although, while the water was boiling, she wondered whether she would remember just what proportion of tea should be used for each cup of water, she passed through the ordeal successfully and was highly praised for her skill.

When the boys indiscreetly offered Elinor her choice among the sights they might see before their return to the city, Elinor too promptly chose the Botanic Garden. In spite of their sophomorific air of worldly wisdom, Robert and Lucian could not quite conceal their dismay at this suggestion, especially as she expressed a desire to see the Shakespeare garden, of which they knew nothing.

"In that case I fear that you will have to lose the glass flowers, as the garden is in just the opposite direction," said Lucian, politely.

"The glass flowers!" cried Elinor, perceiving that her former suggestion had not been received with favor. "Why, of course I would much rather see the glass flowers." And so the whole party set out toward the great museum.

"Not to throw cold water on the efforts of Lucian to guide you to the best that Cambridge offers," said Fritz, "I must tell you that a visit to the glass flowers is almost commonplace. They share with tourists from afar the attraction of Bunker Hill; in the minds of many not to have seen the glass flowers is not to have seen Cambridge. If you wish to be original, pass them by."

"Thank you," replied Elinor; "but really I never have cared especially to be original."

Later, after Elinor had seen not only the glass flowers but many of the other treasures in the great museum, she admitted that even Yale had little better to offer. From the museum the party went on to Memorial Hall.

"It's a pity that you cannot wait a little longer, it would be such fun to see the students at dinner," sighed Martine, for whom human nature always had more interest than tablets and pictures.

"I should love to stay, but I promised to be at my cousin's before six. Yet there is so much to see here in Memorial, these windows and portraits are so fascinating, that it's very hard to go away without studying them all more carefully."

Elinor had barely time for a glance at the portraits and the stained glass windows in the great hall.

"It's the finest hall I ever saw," said the girl from Philadelphia; "I like everything about it except—"

"Except what? This is an age of improvements, and if you'll just mention what you have in mind, so far as Lucian and I can carry out your suggestion it shall be accomplished," and Robert Pringle bowed low to Elinor. Elinor seemed so embarrassed by this mock courtesy that Martine hastened to her rescue. The older members of the party were out of hearing.

"You are as great a tease now as Lucian. I could mention dozens of things that could be done to improve Memorial Hall, handsome as it is." Martine cast about in her mind for something to strengthen her assertion. Up to this moment she had never realized any special imperfection in the great building. But now—

"For example!" she exclaimed emphatically, "just look at these dining-tables in a hall like this. It's casting your pearls before swine. They ought to be taken away."

"Well, I'm glad that Robert and I board at a club table. I should hate to be included in your group of swine, whom you wish to have taken away—"

"Oh, Lucian!"

It was now Elinor's turn to come to Martine's rescue.

"Why, that is just what I meant. I think that the tables ought to be taken away. It seems a pity that Memorial Hall should be a mere dining-room. I should like to see it quite clear of them."

"Then you must come here Class Day. Can't you wait for ours? I'll show you Memorial Hall as it should be—filled with youth and beauty dancing, and not a tablecloth in sight."

"Oh, it doesn't seem the place for dancing either," and Elinor gazed solemnly at one of the class windows, on which were portrayed Epaminondas and Sir Philip Sidney, as examples of valor.

"You must remember, Miss Naylor, that in the long waits between courses, the undergraduates who board here have a fine chance to study these windows, with their lessons of patriotism and valor. This food for reflection goes a long way toward making them forget the real nature of the food served here—"

"Come, come, Robert! Remember you are talking to a Yale girl, and not an ingenuous Harvard maiden. We must not have derogatory reports get abroad."

But Elinor and Martine had no intention of wasting their time listening to Robert's nonsense, and were now pushing through the doors into the transept.

"The real Memorial is here," said Elinor, reverently, passing from one tablet to another, on which were inscribed the names of those Harvard men who fell in the Civil War.

"'The real Memorial is here,' said Elinor, reverently, passing from one tablet to another."

"A short life hath Nature given to man, but the remembrance of a life nobly rendered up is eternal!" she murmured, translating one of the inscriptions on the wall.

"Oh!" sighed Martine. "How wonderful that you can translate Latin at sight! I have taken a tremendous fancy to Latin, but now I'm only in the beginning of Virgil, and I have to look up every other word, and you are not much older than I."

In her admiration for Elinor's ability, she wondered if Elinor had realized the prejudice she had felt when they started on their drive. How strange that in a few hours her feeling toward anyone should change so completely.

Lucian and Robert, slightly bored by the girls' interest in the inscriptions, walked to the door, where they almost ran into Brenda, Fritz, and the rest of the party, who had been strolling through the Yard.

"Your vehicles are here!" cried Fritz. "They are just around the corner—"

"Good enough," responded Lucian. "It's rather boresome taking visitors around Memorial—Oh, they won't hear!" he concluded, as Brenda raised a warning finger. "Come, Martine," he cried in a louder voice, "we are all waiting."

Reluctantly Elinor and Martine turned toward the others. Each had just made the discovery that her companion was a very entertaining girl.

"Who's going in the auto?" asked Lucian.

"Oh, Elinor and I, certainly."

Martine was some distance ahead of Elinor.

"But I thought that was why you scorned the auto coming out to Cambridge—because you didn't wish to ride with Elinor."

"Oh, everything is changed now. She is one of the most charming girls."

"Then she has forgiven you for knocking her down and hitting her with your umbrella?"

"Why, we haven't even spoken of it, though she knows that I know that she—"

"Come, girls, tumble in!" cried Lucian, and Lucian had so many remarkable Harvard tales to tell as they speeded along that neither had time to refer to the rainy-day episode and their first strange meeting.

CHAPTER III

PRISCILLA'S PRIDE

"Why, I never lose my temper! What do you mean?"

"That is what I mean. You seldom lose your temper; I should hardly say 'never.' Neither does Priscilla."

"Well, then, why won't she let me pay for the photographs?" Martine looked keenly at Amy, who had been spending an hour with her that afternoon, as if she expected to read the answer in her friend's eyes.

"I cannot tell you Priscilla's reasons, but her spirit of independence."

"Spirit of independence! Boys of '76! How tired I am of American history! Priscilla is just like one of her own Pilgrim Fathers—only more so. Probably any one of them would have let a friend pay for one of those neat silhouettes, especially if the friend had insisted on having it made, or taken, or cut, or whatever it was that they did to make silhouettes; but Priscilla is a great deal harder than Plymouth Rock, and that is saying no little."

"All the same, you and Priscilla will have to settle this affair for yourselves," and rising from her seat, after a few words of farewell, Amy left Martine to reflect on the matter they had been discussing.

Now the dispute between Priscilla and Martine, if worth dignifying by so serious a name, was not of a kind likely to make lasting trouble between friends. For some time Martine had been teasing Priscilla to have her photograph taken, and Priscilla had never given a decided answer. At last one day, as they passed a fashionable gallery, Martine had insisted that the two should go in merely to look at samples of the photographer's work. On the impulse Martine decided that it would be great fun for them to be taken together. Vainly Priscilla protested that her costume was not suitable, that she didn't feel in the mood for sitting; Martine carried her point and two or three negatives were made of Priscilla and Martine sitting or standing, side by side. Then two or three were made of the two girls, each by herself. When the proofs were sent home, the photographs of Priscilla were exceedingly good. But Priscilla hesitating about ordering the finished pictures, she did not give the whole reason to Martine. Her hesitation came from the fact that the artist was expensive and that she had already exceeded her allowance for Christmas presents.

"I do not think that I can really afford them," she said at last to Martine one day, when the latter asked her if she had made her choice among the negatives. "I should simply love," she added, "to have some for my mother and a few of my relations Christmas, but I shall have to wait a little before deciding."

Yet while she spoke she retained in her hand one proof that seemed to meet her approval.

"Then this is the one you prefer?" said Martine, taking it gently in her own hand.

"Yes, I haven't had a photograph since I was a small girl, but I am sure that mother would be delighted with this one."

A week later a box came by mail to Priscilla. Opening it she found not only a half dozen of the photographs in which she and Martine were taken together, but also a dozen of the single heads, finished in the most expensive style. For a moment she was rather upset by the packet. "Of course there's some mistake," she said. "The man must have thought that I meant to give an order like Martine's, but I can never in the world afford these, and mother would be displeased with me for ordering them. There is only one thing—I'm sure to have some money given me at Christmas, and I can use some, or all of it, to pay this bill."

No bill was contained in the package, and after a few days, when Priscilla went to the photographer's to ask for it, she was told that it was already paid. Then she sought Martine, who did not deny that she had paid the bill.

"Why, it was the proper thing for me to do," she said. "It was I who had the photographs taken, and I who ordered them finished. I can't see that you have much to do with the matter now, except to send the photographs as Christmas cards. I can tell you they'll go like hot cakes, for they are just as good as they can be."

But Priscilla was firm, and though Martine tried to be firmer, she could not get her friend to promise to accept the pictures as a gift.

"They are really not a gift, either," urged Martine, "for I myself wanted to be in a group with you, and you stood there only to oblige me; so certainly you've earned something for your trouble, and as to the single heads, I wanted a separate picture of you, and while the photographer was about it, it didn't cost much more for a dozen than for one."

Again Priscilla presented her side, adding only that she must ask Martine to wait until after Christmas for the sum she had spent.

"If I didn't like the photographs," she concluded, "the whole thing would be different; but I do like them, and I can send them away as Christmas gifts, and so I must pay the bill."

"But it came to me."

"For my photographs?"

"No, for mine; I had them taken. They wouldn't have been printed if I hadn't ordered them."

"Oh, but mine are mine."

"Why, of course they are yours—at least all that were sent to your house."

"I can't bear to be obliged to anyone else for them."

"That's one of your greatest faults, Priscilla; you hate to be obliged to anybody for anything."

So for the present the discussion was dropped, though each friend was determined that in the end she would carry her own point.

This steadfast holding to her purpose was what Martine called Priscilla's "ill-temper," in describing the affair to Amy. Though she inwardly approved of her friend's independence, she felt that after she had approved of it Priscilla ought then to be ready to yield to her.

"It is strange," she said, "that I can never get Priscilla to accept anything from me. 'Pride goeth before destruction,' and that will be the way with Priscilla. Something will surely happen to her if she keeps on like this."

In the early summer, a few months before, Priscilla and Martine had first become really acquainted, when as travelling companions they made a journey with Amy and her mother. For some time the two seemed far from congenial; each looked at life from a very different standpoint. Priscilla, brought up rather strictly and economically, prided herself, perhaps unduly, on her unworldliness, and found it hard to understand the extravagant, fun-loving Martine. But each girl at last accepted the other's good qualities, and before they had left Canadian soil the two had begun to be good friends. When Martine's plans were finally settled, Priscilla was delighted that she and the young Chicagoan were to be at the same school.

Now Priscilla, although for a long time she had spent several weeks of each year in Boston with her aunt, Mrs. Tilworth, had made few friends among the girls of her own age whose parents her mother or her aunt knew. Her natural shyness stood in her way when they came to call on her, and when she returned their calls she progressed no further.

Often she was invited to their parties, and when she could not escape it, she accepted their invitations. Though she took part in their games in a quiet way, no one paid much attention to the pale little girl who always seemed ill at ease.

One awful day Mrs. Tilworth decided that she must give a party for Priscilla; in vain Priscilla protested that she hated parties. The invitations were written and sent out, and on the appointed afternoon Priscilla, in a ruffled muslin gown, had to stand beside her aunt to receive her guests. When she had safely passed through this ordeal she slipped away to a corner, where she sat for a while looking on. When she found that no one tried to draw her out, she managed to slip still farther away. "They don't need me," she murmured. Later, when they looked for her, that she might take her place at the head of the table—for it was a children's party, with a sit-down supper at six o'clock—there was a great uproar when she could not be found. At last two or three of the children went to Priscilla's room, and entering without knocking, they saw her seated in an easy-chair by the droplight on the little centre table. She was so engrossed in the book she was reading that at first she did not hear them, and when one of them snatched the volume out of her hand to read the title, they discovered that it was a little history of Mary Queen of Scots.

"Those children tired me," she explained later to her aunt. "They played so hard, and I just thought I'd go upstairs and read for a while."

Somehow the story got out. Mrs. Tilworth repeated it to one of the older girls, and for a long time Priscilla was called behind her back "Mary Queen of Scots," only someone said, "She will never lose her head, her neck is so stiff."

Martine, when Brenda told her of this story, could not help laughing, in spite of her desire to be loyal to her friend.

"Priscilla is still stiff-necked," she said, "but already since she's had my acquaintance she's been forced to unbend a little, and before another summer comes round her education will be much further advanced."

Priscilla was conscious of her own shyness, and often envied those girls who seemed to have so much fun together.

"I shouldn't expect Priscilla to be very cheerful while she lives with Mrs. Tilworth; the house is really gloomy; it has plenty of windows, but the curtains are always pulled down, and the furniture is so heavy and primly arranged that it naturally affects Priscilla's disposition."

What Martine said was true to a great extent. Mrs. Tilworth's house was halfway up the hill, not so very far from the Mansion School, but its whole aspect, inside and out, was far less attractive than Mrs. DuLaunuy's. It was furnished in the heavy style of about fifty years ago, lacking the elegance of real antiquity. Priscilla's room was large and overfurnished, with its great black walnut bedstead and marble-top table and heavy rocking-chairs. But it wasn't exactly a young girl's room, and the gilt-framed steel engravings on the wall gave her no inspiration for study or work. Secretly she envied Martine her cheerful room in Brenda's apartment, with its couch covered in pink and white cretonne, its white enamelled dressing-table and oval mirror, brass bedstead, and rattan chairs cushioned to match the divan. She did not express her envy of these pretty belongings, lest she should appear ungrateful to Mrs. Tilworth; for she knew that her aunt wished her to be comfortable and happy, according to her own standard of comfort and happiness. Indeed most people who knew Mrs. Tilworth thought Priscilla exceedingly fortunate in having so good a home offered her at a time when her mother was especially burdened with care.

Although Mrs. Tilworth had never expressed herself on the subject, Martine believed that she did not approve of persons who lived in apartments. The little original prejudice that she had against Martine as an outsider was probably somewhat stronger from this fact.

"I should think," she had said to Priscilla, "that Mrs. Stratford must have been greatly disappointed that Mrs. Montgomery could not take Martine this winter; it would have been so much better for her to live in a house."

"But an apartment is just as pleasant," Priscilla had responded, "and it's a fine thing that Brenda Weston was able to take her. Brenda lives in a flat because it's more economical."

"Don't say 'flat'; you've learned that from Martine; in Boston we always say 'apartment.' But an apartment on the Avenue is not economical, my dear child. A whole house on Chestnut Street would cost no more, and though I would not make anyone else's business my own, I can't understand how anyone who might live in a house can prefer a few rooms high up in the air."

"It's very homelike there," sighed Priscilla, casting a glance around the large, gloomy dining-room, where they sat at dinner. "I always enjoy myself at Brenda's—"

Mrs. Tilworth, noticing the sigh, looked sharply at her niece. "I hope you are perfectly happy with me," she said.

"Oh, yes, indeed I am; you are certainly very kind."

Yet even as she spoke, Priscilla realized that in some ways she wasn't benefiting as she should from her aunt's kindness, and she began to wonder if the fault might not lie a little with herself.

A few days after the discussion about the photographs, Priscilla came to school with a letter in her hand.

"It's from Eunice," she said, as she and Martine sat together near a window, a quarter of an hour before the time for the school to begin.

"Oh, read me what she says," urged Martine. "Her letters are always entertaining, because they are so old-fashioned."

Eunice Airton was a young girl near Priscilla's age, whose acquaintance Mrs. Redmond and her party had made during their stay in Annapolis. She was especially Priscilla's friend, while her brother Balfour was Martine's ideal of an independent college boy; and it was rather because she hoped to hear some news of Balfour that Martine urged Priscilla to read the letter.

"I am sorry to say," wrote Eunice, "that I hardly think it will be possible for me to go to college. It will be very difficult for me to overcome the prejudices of my mother, who still does not think it is quite proper for a girl to have the same education as a man. But the fact that you are planning to go to college will have much weight with her, for, as you perhaps know, she thinks you quite a model and says that she never can realize that you are an American."

Martine smiled at this expression of Mrs. Airton's opinion, which indeed she had heard more than once before. "Eunice," she said to Priscilla, "is too polite to repeat all that her mother said in speaking of you. She probably contrasted you with me, whom, I am sure, she considers the typical Yankee girl."

"Oh, no, of course not," protested Priscilla, continuing to read Eunice's letter.

"Before I tell you of any of my own personal affairs, I must mention something that will interest you more deeply. There is an Acadian family living in Annapolis, and whom do you suppose they have had visiting them lately? Why, the little Yvonne, the blind girl, of whom I have heard you speak, who is the special protégée, if I remember, of Miss Stratford. It is indeed due to her kindness, I understand, that Yvonne has been able to make this journey from Meteghan, and I am told that she is to stay here three months under the care of a physician who thinks that he can help her eyes. She is also to take lessons on the piano, as those who are interested in her think that it is better for her to let her voice rest for the present, but to play the piano well enough to accompany her songs will some time be a great advantage to her."

"There," exclaimed Martine, excitedly, "that's a fine idea! I wonder who suggested it to the Babets. It isn't likely that the doctor can do so very much for her eyes, but it will be splendid for her to get a start in music. When I see papa at Christmas I intend to persuade him to have Yvonne brought to Boston for a year."

"Oh, that would be a great expense," said Priscilla, "and someone would have to take care of her."

"That could be managed easily enough, if I can only get papa thoroughly interested."

"I think he has already done his part, for it's through the money he gave you for Yvonne that she is able to be in Annapolis now."

"I wonder how Eunice used her money; did she ever tell you, Priscilla?"

"No," replied Priscilla; "but she may have helped her mother about the mortgage, and perhaps she may have put a little aside for a college nest-egg. She is so practical."

"It's wonderful—isn't it, Priscilla?—that you should have met a girl you approve of so thoroughly in a corner of the world that isn't Plymouth or even Boston."

Priscilla, as she folded up her letter, looked questioningly at Martine. There was something that she did not quite understand in Martine's attitude toward Eunice.

Whatever question she had in mind remained for the time unspoken. It was time for school to begin, and they hurried to their places.

CHAPTER IV

CHANGES

The first week in December a strange thing happened. Brenda had received a letter with a Washington postmark, yet this in itself was not remarkable. Such letters came to her daily, for Arthur had gone to Washington on business a day or two after the trip to Harvard. But her manner, as she rapidly scanned this particular letter, was so unusual that Martine, watching her, knew that it brought news out of the ordinary.

The slight frown on Brenda's face deepened as she read the four or five pages, and when she had finished she flung the letter down on the floor.

"Oh—it seems too bad," she sighed, in response to Martine's look of surprise. "Just as we are settled, to have to give everything up!"

"Give up—what?" asked the puzzled Martine.

"Why this—everything—our apartment—Boston—oh, dear—of course I knew it might come—but I hoped next year."

As Brenda finished there were tears in her eyes, and still Martine did not wholly understand.

"Of course I am sorry," said Martine, "since it's something that troubles you. But would you please tell me what it is all about?"

"Well—it's Arthur's business," she explained. "A promotion that he has expected has come. It took him some time to find out what he really could do after he left college. The office in San Francisco is more important just now than the one in Boston. He is needed there for six months—and we must go at once—yes," she concluded, looking at the letter a second time. "We must be there by the first of January. Well, fortunately, we need not give up this apartment, for we have a two years' lease, and it wouldn't be worth while to sublet it, as we may return in six months. So you see, my dear, that things might be worse. I shall have to pack only my clothes and small belongings, and after all, it will be rather fun to see a new corner of the world."

"What you say sounds practical—except—you seem to have forgotten me."

"Oh, you poor child, how selfish I am! Why you could just stay on here with the cook and Maggie, or Angelina, if you prefer her."

"Brenda Weston! You know that would never do! I mean other people would say it would never do."

"There, there, child, don't worry," said Brenda, assuming her most elderly manner. "I will write to your mother, and between us something delightful will be arranged. What a shame you are in school," she concluded, forgetting for the moment her position as Martine's temporary guardian. "Except for that you might go to San Francisco, or even travel with your mother."

"I am growing fond of school," replied Martine, as she returned to her book. "Even to go to California I wouldn't give it up, but if it's really settled that you are going, I must write home at once."

In a few days Brenda and Martine both received answers to their letters to Mrs. Stratford. To Martine what her mother wrote was even more surprising than Brenda's change of plans.

"Your father has to go to South America on very important business. It is too long a journey for me, although I am much stronger than a year ago. We think the wisest plan would be for me to go to Boston to be near you and Lucian, and I am writing Mrs. Weston to see if we may not engage her apartment for the next six months."

"Hurrah!" cried Martine, turning to Brenda, who had just finished reading the letter Mrs. Stratford had written her. "Of course you'll say 'yes.' Oh, how perfectly happy I shall be to have mother with me."

"Of course I will say 'yes.' But please spare my feelings; if you are too happy you will forget to miss me."

"Oh, never, never; but then mother must be feeling much stronger, and I have seen her so little the past few years. She has been under the doctor's care or travelling, and our Chicago house has been closed so long, and hotels are so unhomelike. But now, with this apartment to ourselves, and Lucian coming in from college—oh! it will be delightful."

Again Brenda protested that Martine was unfeeling in counting her out so completely.

"But I can't count you in, when you calmly and deliberately plan to turn your back on Boston and me. You know that I shall miss you, but to have mother here—of course that makes all the difference in the world."

For the Christmas holidays Lucian and Martine joined Mr. and Mrs. Stratford in New York. A day or two after Christmas, Mr. Stratford sailed for England, whence he was to embark for South America. Martine could but notice that the sadness that her father showed during these last days seemed due to something besides the fact that he was to be absent from his family for a few months. He had often before gone on long journeys, but usually he made an effort to have his departure particularly cheerful.

"Your father is worried," her mother said; "his business is not going just as it should. He hopes that this visit to South America will straighten out some things. If it does not—well, we needn't talk of the future now. I am glad that we are all together this Christmas. You and Lucian must do all you can to divert your father, he has so much to trouble him."

Martine took this advice to heart, and though Mr. Stratford spent some hours each day downtown, after luncheon she always insisted that he must entertain her. By this she meant that she must entertain him, and in consequence she thought out all kinds of odd ways of amusing him. One day they sailed on the Ferry to Staten Island to visit Sailors' Snug Harbor. Another afternoon they went up to Van Cortland Park to see the old Van Cortland house. One day they wandered for an hour in the Bowery, but Martine admitted that this wasn't as entertaining an expedition as she had imagined it would be from the accounts she had read of it. The shops on the whole seemed commonplace, and the crowded cross-streets of the East Side looked far more interesting, as she caught glimpses of them in passing.

She had to let these glimpses satisfy her, as she had promised her mother not to explore any out-of-the-way corners of the tenement district; and so obedient was she in this that she would not even go inside a certain Bowery pawnshop in whose windows she saw a fascinating little guitar. Instead she urged her father to price it, and when he came outside with it under his arm she accepted it with delight.

"It's neither a violin nor a guitar," Mr. Stratford explained, "but the little instrument that the Sandwich Islanders love."

Martine was delighted by this account of her new treasure, and she carried it home with great pride. But unconventional expeditions were not the only pleasures that Martine shared with her father. One day Mrs. Stratford drove with them through the Park up beyond Riverside and Grant's tomb. Two or three afternoons they spent with relatives, of whom Mr. Stratford had a number in New York. Lucian was little with his father during the holidays. Classmates at Ardsley and Trenton and Germantown claimed short visits from him. But on Christmas Day he joined his parents at the small uptown hotel where they were staying.

"Martine," he said as they sat at breakfast, "Elinor Naylor was at the Harbins' dance night before last in Germantown. She took a lot of trouble to introduce me to some of her best friends just because I was your brother. I tell you what—you made a great impression on her."

"I certainly did—the first time we met," responded Martine, smiling, and Lucian did not quite understand, because his sister had never really explained the circumstances under which she and Elinor had first met. With slight urging from Martine, however, Lucian plunged into a description of the Harbins' dance, and though boy-like he could not describe what Elinor wore, he declared that whatever it was it just suited her, and that she certainly was a regular peach, "and the funniest thing about it is that you don't think about her being pretty when you first see her. It's only when you begin to remember her that you realize how good-looking she is."

"Poor Priscilla," sighed Martine in mock sorrow, "I fear her nose is out of joint."

"Oh, no—at least, what do you mean?" asked Lucian, and at this moment the entrance of Mr. and Mrs. Stratford put an end to their fun.

The Christmas breakfast, in spite of Martine's efforts, passed off rather quietly. Her parents both seemed sad and disinclined to talk. Even the unobservant Lucian at last noticed this and tried to turn the conversation into cheerful and impersonal channels, with poor success. Their Christmas dinner was at the house of an elderly cousin of the Stratfords in Washington Square. The guests were nearly all relatives of Martine's father, and the young visitor received abundant criticism, favorable or unfavorable, according to the dispositions of the various critics.

But even those who thought Martine a little forward or too self-possessed for a girl of her age could but admire her frank, cheery manner and the consideration that she constantly showed for older people. The less conservative found her charming and complimented her on her clever way of telling a story. Some said she looked like her father, some like her mother, and the oldest cousin of them all, taking her aside said, "You are just like your father's mother when she was your age. She had your coloring and your bright brown eyes. I knew her well when I was a girl. She was said to be the image of her French grandmother, and I can wish you nothing better than to grow up like her," and as the old lady kissed her Martine felt her own eyes moistening.

"I am glad that I have some French blood in my veins," she said a little later; "the Huguenots were so wonderful. I wish that papa and I had time to go up to New Rochelle, for although I believe there's little left there of the Huguenots now except the name, I should like to see the place because my forefathers lived there."

Lucian found the Washington-Square dinner rather a bore, although he managed to conceal his feelings until with his family he was back at the hotel.

"They might have asked at least one girl near my age," Lucian said. "No wonder you were such a belle, Martine, among all those antiquities," a compliment that Martine refused to accept until Lucian admitted that she possessed qualities that would make her popular even in a younger crowd.

One of Martine's Christmas gifts did not surprise her,—a complete set of brushes, mirror and little boxes to replace those she had lost in the Windsor fire. This did, however, surprise Lucian, who knew that his father had promised Martine a full set of silver.

"Why, how is this?" he asked, as Martine spread out her new possessions before him on a table. "Is plain black wood more in fashion than silver? It must be, or you wouldn't have it."

"But this is pretty; don't you think so?" asked Martine, always anxious for her brother's approval.