Brenda, Her School and Her Club

Helen Leah Reed

Brenda,

Her School and Her Club

BY HELEN LEAH REED

Author of "Miss Theodora," Etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY JESSIE WILLCOX SMITH

BOSTON

LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY

1900

Copyright, 1900,

By Little, Brown, and Company.

All rights reserved.

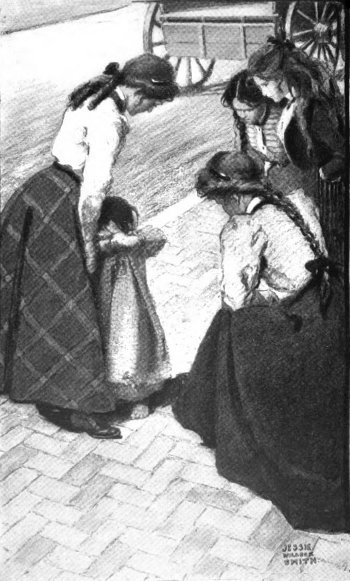

"The child himself, surrounded by a group of curious girls, clung to Nora's hand"

CONTENTS

I. Four Friends

II. Julia's Arrival

III. The Rescue

IV. A Club Meeting

V. Miss Crawdon's School

VI. Misunderstandings

VII. Visiting Manuel

VIII. Planning the Bazaar

IX. A Mysterious Mansion

X. A Sophomore

XI. The Cooking Class

XII. Concerning Julia

XIII. Great Expectations

XIV. The Football Game

XV. A Poet at Home

XVI. An Historic Ramble

XVII. The Rosas at Home

XVIII. Merry Christmas

XIX. Nora's Thoughtlessness

XX. Fidessa and Her Mistress

XXI. Miss South and Julia

XXII. Brenda's Secret

XXIII. Almost Ready

XXIV. An Evening's Fun

XXV. The Bazaar

XXVI. Great Excitement

XXVII. A Mistake

XXVIII. Explanations

XXIX. After Vacation

XXX. Brenda's Folly

XXXI. The Shiloh Picnic

RECENT BOOKS FOR THE YOUNG

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

"The child himself, surrounded by a group of curious girls, clung to Nora's hand"

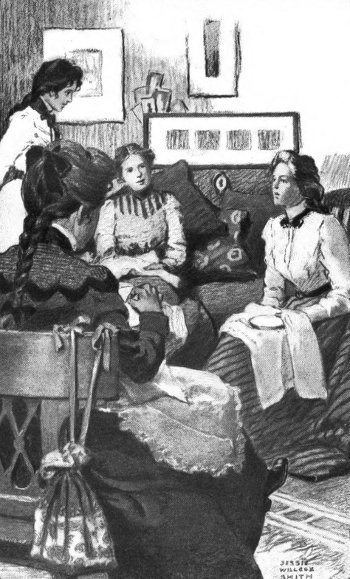

"'Oh, I'll tell you what, girls,—let us work for—Manuel!'"

"She was able to rush on and pick them up as they were dashed against a lamp-post"

"Now as Julia sat there drinking tea from the quaintest of old-fashioned china cups"

"'Why, Brenda Barlow, why are you lying in this downcast position?'"

BRENDA, HER SCHOOL AND HER CLUB

I

FOUR FRIENDS

"What do suppose she'll be like?"

"How can I tell?"

"Well, Brenda Barlow, I should think you'd have some idea—your own cousin."

"Oh, that doesn't make any difference. I've hardly thought about her."

"But aren't you just a little curious?" continued the questioner, a pretty girl with dark hair.

"No, Nora, I'm not. She's sixteen and a half—almost a year older than we are. She's never lived in a big city, and that's enough."

"Oh, a country girl?"

"I don't know that she's a country girl exactly, but I just wish she wasn't coming. She'll spoil all our fun."

"How?" asked a third girl, seated on the bottom step.

"Why, who ever heard of five girls going about together? If three's a crowd, five's a perfect regiment. I agree with Brenda that it's too bad to have her come. Now when there's four of us we can pair off and have a good time."

The last speaker had a long thin face with a determined mouth and large china blue eyes. She was the only one of the four whom the average observer would not call pretty. Yet in her little circle she had her own way more often even than Brenda, who was not only somewhat of a tyrant, but a beauty as well.

They carry a spell,"

the other girls were in the habit of singing, when the two Bs had accomplished something on which they had set their hearts. Edith, the third of the group, in spite of her auburn hair, was the most amiable of the four. I say "in spite" out of respect merely to the popular prejudice. Nobody has ever proved that auburn hair really indicates worse temper than hair of any other color. Edith almost always agreed with any of the plans made by the others, and very often with their opinions. Dark-haired Nora was the only one of the group who ever ventured to dissent from the two Bs. Now she spoke up briskly,

"I know that I shall like your cousin."

"Why?" the other three exclaimed in a chorus.

"I can't tell you why, only that I know I shall."

"You're welcome to," said Brenda, tossing her head, "but I guess if you had just begun to have your own house to yourself you wouldn't like somebody else coming that you'd have to treat exactly like a sister."

"Why, Brenda!" said Nora, with a look of surprise, and then the others remembered that Nora had had a little sister near her own age whose death was a great sorrow to her.

"Why, Brenda!" repeated Nora, "I wish that I had a sister."

Now Brenda Barlow was not nearly as heartless as her words implied. She had two sisters whom she loved very dearly. But they were both much older than Brenda, and by petting and spoiling her they had to a large extent helped to make her selfish. One of them had now been married for four years, and had gone to California to live and the other was in Paris completing her art studies. When Janet married, Brenda had not realized the change in the family. But when Agnes went to Paris, Brenda was older, and she fully felt her own importance as "Miss Barlow."

"It's the same as being 'Miss Barlow,'" she said to her friends, "the servants call me so, and I've moved my things down into Janet's room. I can invite any one I want to luncheon without asking whether Agnes has any plans,—and I shouldn't wonder if I could have a dinner-party once in a while—of course, not a very late one, but with raw oysters to begin with—sure—" and the other girls laughed, for they knew that Brenda had been practising on raw oysters for a long time, and that she felt proud of her present prowess in swallowing them without winking or making a face.

Mr. Barlow was generally absorbed in business affairs, and Mrs. Barlow had so many social engagements that Brenda did as she wished in most respects. She ordered the servants about when her mother was out, and they were as ready to obey her as her friends were to follow her lead, for when Brenda wanted her own way she never seemed ill-natured. She simply insisted with a very winning smile—and nobody could refuse her.

She had found it very pleasant to rule her little world. It was even pleasanter than being the spoiled and petted child that she had been when her sisters were at home. Her father and mother had never seen how fond she was growing of her own way until they announced the coming of her cousin Julia.

"She is older than you, Brenda, and I hear that she is far advanced in her studies. I dare say that she will be able to help you sometimes."

"Oh, papa! I hate to have any one help me. She'll be an awful bore, I suppose, if she thinks she knows more than me——"

"Grammar, Brenda," said her mother with a smile.

"Well, then, more than I," repeated Brenda.

"I'm sure she won't be a bore, Brenda, but her life has been very different from yours. She has led a quiet life, for you know she was her father's constant companion until he died."

Here Mrs. Barlow sighed. Julia's mother was Mrs. Barlow's sister, and had died when the little Julia was hardly five years old.

"Uncle Richard was always delicate?" ventured Brenda.

"Yes, dear, and he spent his life trying to find a place where he could gain perfect health. Boston was too bleak for him, and that is why you have not seen Julia since she was very little. Your uncle did not care to undergo the fatigue of traveling East even in the summer, and he could not bear to be parted from Julia. But she was always a sweet little thing."

"I hope you won't be disappointed in her," cried Brenda, half in a temper. "I believe you are going to care for her more than you do for me."

"Nonsense, Brenda," exclaimed her mother in surprise.

"Well, you can't expect me to feel the same about her,—a strange girl—who knows more than I, and is just enough older to make every one expect me to look up to her. Oh, dear!"

Since Brenda had not concealed her feelings from her mother, it was hardly to be expected that she would be less frank with her three most intimate friends.

After Nora and Edith had bade Brenda good-bye that afternoon when they had talked about the unknown cousin, they walked rather slowly up the street.

"Do you suppose Brenda's jealous?" said Nora, in a half whisper.

"Oh, hush," answered Edith, to whom the word jealousy meant something dreadful. "Of course not."

"Well, don't you think it's strange for her not to feel more pleased at the prospect of having her cousin with her. I should think it would be great fun to have another girl in the house."

"Oh, well, Brenda can always have one of us. Her mother is so good about letting her invite people—and of course she can't tell how she'll get along with her cousin. No, I really shouldn't like it myself."

As Nora and Edith walked away, Brenda turned to Belle, in whom she always found a ready sympathizer.

"You know how I feel, Belle."

"Yes, indeed; I think it's too bad. I'm sure it will spoil half our fun. It's horrid anyway to have some one older than yourself ordering you round."

"Oh, I don't suppose she'll do that exactly."

"Well, it's just the same thing. If she's such a model, as your mother says, she'll make you feel uncomfortable all the time. Then if she's wearing mourning, she can't do the things that you do, and you'll have to stay at home and be polite to her. Yes, I'm really sorry for you, Brenda."

With sympathy like this, Brenda began to regard herself as almost a martyr.

"Oh, dear," she sighed, "why couldn't she have waited until next winter? Come, Belle," she continued, "you'll stay to dinner, won't you?"

Belle hesitated for a moment. "I suppose I ought to go home."

"Oh, why?"

Belle was silent. She knew that certain unfinished lessons awaited her, and that her grandmother objected to her dining away from home, unless she had first asked permission. She fortified herself, however, by saying to herself, "Oh, well, mother won't care." For her mother was what is commonly known as easy-going, and seldom interfered with her daughter's goings and comings.

Belle always enjoyed dining with Brenda. The dining-room was so attractive with its great blazing fire, its heavy draperies and cheerful oil-paintings on the wall. At home she sat down in a large, severely furnished room, with her solemn grandmother wrapped in a white knitted shawl at one end of the long table, her half-deaf uncle James at the other end, and her brother Jack on the side opposite her. Her delicate mother often dined upstairs. Uncle James usually had some story to tell of misdeeds that he had heard some one ascribe to Jack ("and how a deaf person can hear I don't see," Jack would say crossly to Brenda). Her grandmother generally read Belle herself a lecture on paying proper respect to one's elders, or some similar subject, while Belle and Jack exchanged glances of mischievous intelligence, which often drew strong reproofs from their grandmother, and sometimes from her mother when she was present.

No wonder, then, that Brenda's invitation was a strong temptation to Belle.

"Come, silence gives consent," laughed Brenda. Dragging Belle by the arm, she touched the door-bell, and in a moment the two girls were inside the house.

"What room is Julia going to have?" asked Belle, as they ran up the front stairs.

"Well, you will be surprised; that's one of the things that makes me so cross. Just think of it, Agnes's rooms in the L—that sweet little studio that I wanted mamma to let me have—it's all fitted up for Julia. Don't you call that mean?" Belle pressed her friend's hand.

"You poor thing!"

"Yes, it seems Agnes is sure not to come home for two years, and so mamma thought the studio would be a good place for Julia to practice in, and so there's a piano and—well—let's come and see. We've got time before dinner."

Pushing open a door on the second floor and going down a step or two, Brenda and Belle found themselves inside a little reception-room. The walls were a deep red, there was a cashmere rug on the polished floor, a clock and two bronze figures on the mantelpiece. An open bookcase in one recess, a short lounge in the other, a low wicker tea-table, and two or three small chairs made up the furnishing.

"This is just the same as it was," said Brenda, "and so is the bedchamber," pointing to a door on the left of the reception-room, "but see here!" and she turned to the right. Belle followed, and they found themselves in a long, narrow room, with a bay window at one end and a skylight overhead. On the walls were several large unframed sketches in black and white, together with water colors and a number of fine photographs and engravings in gilt or ebony frames. Against the wall near the bay window stood a small upright piano with an elephant's cloth scarf over the top. The groundwork of the scarf was of a deep yellow, harmonizing with the tint of the painted walls. There were two or three comfortable chairs covered in yellow-flowered chintz, and in the centre an inlaid library table with a baize top and an assortment of writing utensils. There were several rugs of a prevailing yellow tint on the polished yellow floor, and one side of the room was occupied by rows of low open book-shelves which held, however, only a few books.

"I believe Julia's going to have her father's library brought here," said Brenda, in explanation of the empty shelves. "Don't you hate book-worms?"

"Yes," responded Belle, "but how lovely this room is! What a shame that you couldn't have it yourself! Why, I thought your mother said that they were going to leave the studio just as it was until Agnes came home."

"Well, so they were, but she won't be home for two years, and then she'll probably have a studio down town, and so they've put most of her things away and fitted up this room just for Julia. She has to have everything."

"I know just how you feel," and Belle pressed Brenda's hand sympathetically. "But then, your own room is lovely."

"Oh, yes, of course; but it isn't the same thing as a studio. A studio is so—so artistic."

The girls were standing in the bay window, bathed in a flood of sunshine from the setting sun. They glanced across the broad river toward the roofs and spires of Cambridge. A tug-boat went puffing along the stream towing a schooner loaded with lumber.

"Oh, my, it must be late! the sun is just dropping behind those Brookline Hills. Come up to my room."

The room on the floor above the studio which had formerly been Janet's, also overlooked the river. It was in the main house and its windows looked down on the roof of the L containing the studio. In fact, the studio to a slight extent impeded the view of the river which was obtainable from this upper room. But the room itself was large and cheerful, with a carpet and paper of bluish tint, a large brass bedstead canopied with blue, comfortable lounging chairs, a dainty little sofa, dressing-table, desk, and all kinds of pretty ornaments. A half-open door showed the adjoining dressing-room with its long pier-glass, and a coal fire blazed in the open grate.

"Make yourself comfortable," said Brenda hospitably, "for if you don't mind, I'm going to write a note that I want to send out by Thomas before dinner. It won't take me ten minutes."

Brenda sat down at her little desk, while Belle sank in the depths of an easy chair near the fire.

Just as Brenda finished her note, a white-capped maid came into the room.

"Oh, Jane, just give this note to Thomas, please. I want him to take it to Mrs. Grey's and bring back my new coat. I can't go to school to-morrow without it."

"I don't hardly think Thomas can go, Miss Brenda."

"Why not?"

"Well, he's got to go to the station for your cousin."

"My cousin?"

"Yes, miss. A telegram came this afternoon that she'd be here at six-thirty, and your mother left word when she went out that they wouldn't be much later than that getting back from the train."

"Well, I never! The idea of her coming without any one's expecting her. Why didn't she write?"

"I don't know, miss. I heard something about a letter that got lost, but anyway your mother's gone to meet Miss Julia, and she left word she thought you'd better give up going to the tableaux this evening, for she wouldn't like you to leave your cousin alone."

"There, Belle, that's the way it's always going to be. Everything for 'Miss Julia.' I don't care, I'm going out just the same. The idea of losing those tableaux."

"But, Brenda," began Belle.

"No, it isn't any good arguing with me. I never could bear to be interfered with, and mamma knows perfectly well that I want to see 'The Succession of the Seasons.'"

"But it's to be repeated to-morrow evening. You know I'm going then."

"I don't care. I hate to go the second night to anything."

Belle did not reply, though as Jane left the room, she turned to Brenda.

"I'd better not stay to dinner to-night."

"Oh, do. I don't want to sit alone with Julia. I shan't know what to say to her. No, really you can't go home."

Then running to the stairs and calling after Jane, Brenda cried,

"See that there's an extra place at the table for Belle."

After this she began to open the drawers of her bureau, tossing their contents about, and she ran in and out of her closet to bring out one gown after another for Belle's inspection.

"Which would you wear if you wanted to make a good impression on a new cousin? I want to look as old as I can, and I believe I'll do up my hair."

"Oh, Brenda!"

"Yes, I will. Now see, if I put a string on the band of this skirt it will almost touch the floor. There, help me."

When the skirt was lengthened, Brenda regarded her reflection in the pier-glass with great satisfaction. Brushing her waving brown hair to the top of her head, she gathered it in a soft knot, and thrust a long gold pin through it.

"Tell me the truth, Belle, wouldn't you think me sixteen years old—if you didn't know," she cried to her friend, who could hardly conceal her mirth at Brenda's changed aspect.

"I don't—why, yes, of course," as she saw a frown stealing across Brenda's face.

Brenda strode around the room with all the dignity she could command, her pretty face somewhat flushed by her exertions in giving her hair just the right touch. As a matter of fact she looked rather odd, but Belle did not dare tell her that her skirt hung unevenly, and that two or three short locks of her hair stood out almost straight behind.

"Hark, I believe they've come," Brenda exclaimed.

Certainly there was a noise in the hall below.

"Where's Brenda?" she heard her mother call.

"Well, I suppose we'll have to go down," she said reluctantly to Belle, and the two girls slowly descended the stairs.

II

JULIA'S ARRIVAL

As the two girls went downstairs, Brenda politely urged Belle to go ahead of her. She, herself, lingered a moment to look over the balusters, and thus, when they reached the broad hall at the foot of the stairs, she was several steps behind her friend.

Belle, with a quick eye, before she reached the bottom of the stairs, noticed a little group near the fireplace,—an elderly woman with a shawl over her arm, who looked like a maid; Mrs. Barlow, holding the hand of a slight girl in black, and last but not least, a large Irish setter which lay at the young girl's feet. All this Belle had hardly time to notice when the young girl rushed forward and throwing her arm around her neck, cried,

"Oh, Cousin Brenda, I'm so glad to see you." Belle for a moment looked disconcerted, and Mrs. Barlow, without showing any surprise at Belle's presence, relieved the latter by saying:

"This isn't Brenda, Julia, but one of her friends."

Julia, still with her hand in Belle's, smiled pleasantly.

"I'm glad to see you," she said, and just at that moment Brenda came in sight.

Julia was hastening forward to greet her cousin as she had greeted her friend, but something in Brenda's face forbade her. Brenda could not, perhaps, have explained why she felt so annoyed at Julia's mistake. She was not unduly vain, yet it annoyed her that her cousin had mistaken Belle for her. For well as she liked Belle, she knew that all the other girls considered her not especially good-looking. Though she could not, probably would not, have put it into words, the thought flashed through her brain that Julia was stupid to have made such a mistake. The thought took form in a rather repelling glance as her eye met her cousin's.

"Come, Brenda, you should not make Julia go more than half-way to meet you," called her mother from her place near the fire.

"No'm," replied Brenda, hardly knowing what she said, for really she felt a little shy about the new cousin, who was more than a year her senior. "With her hand outstretched, she stepped toward Julia, moving with the dignity that her lengthened skirt demanded.

"Dear me! What can it be?" she thought, as she felt something hindering her progress. It could not be that the skirt was too long. She stooped a little to raise it from beneath her feet, and then, how mortifying! she felt a string snap. She clutched wildly at her skirt with both hands. But it was too late, and making the best of the situation, she stood before her cousin in her short ruffled petticoat, instead of her long, grown-up gown.

"There, Brenda," cried her mother, comprehending the situation at a glance, for this was not the first time that Brenda had tried to lengthen her skirts. "There, Brenda, I hope you won't be as foolish as this again. Speak to your cousin, and then go up and put on your skirt properly."

Poor Brenda! What a loss of dignity! She hardly knew what she said to Julia, or what Julia said to her. She resented Belle's offer of help, for had she not heard a decided giggle from her friend at the moment of the catastrophe? So rushing to her room, she locked the door and did not leave it until called to dinner.

Now Brenda, though by no means perfect, was not ill-natured, and she seated herself at the table with the intention of making herself agreeable to Julia.

But there are times when nothing seems to go exactly right, and this evening was one of them. In the first place it disturbed Brenda to see her father's glance of amusement as his eye fell on her new style of hair-dressing.

"Which is it now?" he laughed, "Marie Antoinette or Queen Elizabeth? Dear me, Brenda, it's a long time since we've seen you masquerading in this fashion."

Brenda reddened. In spite of the mishap to her dress, she wished her cousin to believe that she always wore her hair on the top of her head. Vague hopes were floating through her mind that she could persuade her mother to let her give up her childish pigtail altogether.

"Why does papa always say things like that?" and she reddened still more as Julia's eyes fell on her. She remembered, however, her duties as assistant hostess.

"Did you have a pleasant journey?" she asked politely.

"Yes, indeed," answered Julia. "That is, I was just a little tired, but it was so delightful to look out of the car window and know that I was really in Massachusetts. It seemed too good to be true."

Mr. Barlow looked pleased. "Ah, Julia, it gratifies me very much to have you say this. Sometimes when people have traveled they lose their love for their early home."

"Yes, Uncle Robert, I've always loved to think of Boston as my real home. Although it's so long since we lived here."

"Why, what do you really remember of Boston?" asked Mr. Barlow.

"Well, the State-House, Uncle Robert, and the Common—of course—and—and Brenda."

"Oh, you can't remember Brenda?"

"Yes, indeed I can. She was the dearest little thing! You see when I was five years old, Brenda seemed almost a baby—a year and a half between two girls makes a good deal of difference,—when they're little."

But even this last saving clause did not prevent Brenda's heart from giving a sudden thump, especially as she caught a sympathetic glance from Belle which seemed to say,

"Ah, she's reminding you how much older she is than you."

Brenda straightened herself up. She tried to think of something to say that would show that though younger, she at least had some knowledge of the world.

"Can you eat raw oysters, Julia?" were the rather strange words that came to her lips. Julia, unable naturally to follow the train of thought leading to this question, answered brightly,

"I've never tried. You see we don't have very good oysters in the West, and some way I've never thought I'd like them raw."

"Oh, if you want to seem really grown-up you'll have to eat oysters off the shell," said Mrs. Barlow. "I believe Brenda has practised so that she can eat them without wincing."

Then Belle, who prided herself on her tact, hastened to change what she knew might become a sore subject with Brenda.

"Were there many people you knew on the train, Miss——"

"Oh, please say Julia," broke in the young girl. "Every one always does. No, there wasn't any one I knew in the cars between here and Chicago. If I had not had Eliza I should have been very lonely."

Brenda had subsided into an unwonted silence. She was wondering how she could excuse herself to her cousin—whether her mother would really make her give up the tableaux for that evening. She heard, without really listening, an animated conversation between her father and Belle on the best way of learning history. Belle believed that more could be learned by general reading than by studying a text-book. "Belle always has so many theories," Brenda was in the habit of saying.

"I wish Jane would hurry with the coffee," she cried.

"Why, Brenda," and her mother looked surprised. "You are not going to have coffee."

"Of course, you know you always let me have a little cup when I'm going out."

"But you are not going anywhere to-night. Didn't you get my message?"

Brenda understood well enough that her mother did not wish to discuss the question of her leaving her cousin when Julia herself was present, yet she persisted.

"But, mamma——"

Mrs. Barlow shook her head. "There is nothing to be said. You know, Brenda, when I mean a thing I mean it."

Julia looked a trifle embarrassed, realizing that in some way she was a hindrance to a full discussion between her aunt and cousin.

Brenda's face was twisted into a curious scowl. She was forgetting her duty to her cousin.

"Oh, mamma, I've made up my mind to go."

"No, Brenda, it is impossible. Let us hear no more about it."

"What is it, Brenda, that you wish to do?" asked Mr. Barlow, who while talking with Belle had only half heard the conversation between Brenda and her mother.

Mrs. Barlow shook her head. She did not care to enter into a discussion before Julia likely to make the young girl feel that her arrival had interfered with any plan of Brenda's.

Then Belle, who realized that she was not always in favor with Mrs. Barlow, saw her opportunity.

"If Brenda will change with me, she can have my ticket for to-morrow evening."

"Why, that is very kind in you, Belle, but have you time to get ready?"

"Oh, yes, if you'll excuse me now," and before Brenda could remonstrate, she saw Belle receive the tickets from Mrs. Barlow's hands and heard her hasty words of good-bye as she started home under the escort of Thomas.

Neither Mr. nor Mrs. Barlow took any notice of the cloud on Brenda's face. Fortunately they could not read her reflections on the duplicity of Belle, who after pitying her so in the afternoon, had now begun to side against her. This at least was the form which Brenda's thoughts took. Rightly or wrongly she considered herself an ill-used young person.

Just then the maid entered with a letter on a salver. Mrs. Barlow glanced at it and then laughed.

"This explains the mystery, Julia, you wrote 'New York' instead of 'Boston,' and so your letter has been two days longer than it should have been in reaching us."

"Oh, did I, Aunt Anna? How stupid! Well, you have treated me much better than my carelessness deserved."

"Well, I'm only glad that I happened to be at home when your telegram came. It would have been a little cheerless for you had you happened to arrive when we were all out. But come, you must be tired."

"Oh, not very." Then, as they left the room, Julia threw her arm around Brenda.

"I know that we shall be great friends."

Already Brenda had begun to return to herself. She hoped that Julia had not noticed her ill-temper. Perhaps after all she should like this new cousin better than she had expected.

"If I were you, Brenda, I'd take Julia to her room now," said Mrs. Barlow.

"How lovely!" exclaimed Julia, as they entered the pretty bedroom near the studio. "Am I to have this all to myself?"

"Yes," replied Brenda.

"I never saw so pretty a room! How I shall enjoy it! Whose used it to be?"

"Oh, it was Agnes's room. She had it decorated to suit her ideas. You know she's an artist."

"Oh, yes. How delightful to be an artist. I wish that I had some special talent."

"I thought you had. Some one, mamma I think, said that you were musical."

"So I am in a way. I've given more time to music than to anything else. But that was chiefly to please papa."

Here Julia sighed, while Brenda hardly knew what to say.

"You must miss him very much," she ventured.

"Oh, don't speak of it, Brenda. I can't bear to think that he is really gone." And Julia's tears began to fall.

"What shall I say?" thought Brenda, and as her words of sympathy were beginning to take shape, her mother entered the room. Wisely enough, she made no comment on Julia's tears, believing that they would flow less freely if she seemed to take no notice of them.

"I have come to see if you are perfectly comfortable. To-night Eliza will sleep on the lounge in your room, and after this we will arrange a bed for her in the room across the hall. In either case you will not feel lonely."

When Julia had thanked her aunt for her kindness, Mrs. Barlow drew Brenda one side.

"Now, Brenda, we must bid your cousin good-night," and then, with a final word or two of advice to Julia, Mrs. Barlow with Brenda left the room.

"I'm going to bed now, mamma," said Brenda, as they reached the hall.

"Very well, I haven't time myself to tell you that I think you have behaved very foolishly this evening. I hope you will be more sensible to-morrow."

"Good-night," cried Brenda, without making any promises.

When she was within her own room she flung herself down on her bed.

"I know just how it will be," she said to herself. "I can never do what I want to. It will always be 'Julia, Julia.' She isn't so bad herself, but it's the way every one will treat me that I hate."

With these confused words on her lips she began to get ready for bed.

III

THE RESCUE

Brenda started for school a little later than usual the morning after Julia's arrival. As she walked up Beacon Street she saw Edith and Nora ahead of her, half-way up the slope on the sidewalk next the Common.

"Oh, dear, they might look back," she said to herself. But they neither looked back nor paused on their way, and Brenda was prevented from hurrying by a line of wagons and street cars which blocked Charles Street. She was kept standing for two or three minutes at the street crossing, and when she continued her way Edith and Nora had turned into the side street leading to the school. When Brenda reached the school door, Belle was the centre of a group of girls seated on the steps.

"Why didn't you call for me, Belle?" cried Brenda petulantly.

"Oh, I had to do some errands on the way, and I thought, too, that you would stay home with your cousin."

"Well! I should say not. I shall see enough of her."

"Tell us about her, Brenda," cried Nora who came out from the house for a moment. "Belle says she has come. What is she like?"

"Like? Why, like any girl. There's nothing special about her. She wears black and I think she feels kind of superior. It's going to be awfully hard for me."

"Yes, Brenda," said a thin-faced girl in the group back by Belle. "You don't think any one could be superior to you, do you?"

Brenda, with her back to the sidewalk, was ready with a sharp reply, when a warning look from one of the girls closed her lips.

"Why, girls," said a cheerful voice behind her, "ought you not to go inside now? You should be in your seats by twenty minutes past nine. I have said many times that you were not to wait for me."

The girls all respected Miss Crawdon, and they were just a little afraid of her. Her authority was not always agreeable, when she chose to make them feel it. Miss Crawdon was tall and blonde, with eyes some one said "that saw everything." These were the right kind of eyes for the principal of a girls' school. She had a pleasant voice with a tone of decision in it that no one dared dispute. At her words the girls seated on the steps slowly arose, and in a very short time they were at their desks, getting out books and preparing for the day's work.

Brenda and Belle occupied adjacent seats. Edith and Nora were in the same room, though a little nearer the window. They with about ten other girls formed what might be called the middle class of a school of forty. There were about fifteen older girls who would stay in school one or two years longer, while Brenda and her friends had three years before them. At least they would not "come out" for three years.

The older girls naturally kept much to themselves. They "did up" their hair, wore skirts almost touching the ground, and were in every way envied by their juniors. The youngest girls of all concerned themselves very slightly about the oldest of all. But the girls of Brenda's age imitated in many ways the doings of these older girls, and when, as occasionally happened, one of the graduating class invited a younger girl to walk with her at recess, the latter for a day or two after was treated with great deference by her companions.

These oldest girls were not ahead of their schoolmates in all their studies. In Latin and mathematics some of them recited with the younger girls, or it might be fairer to say that some of the brighter young girls were in the classes with the elder. Edith, for example, was ahead of Brenda in mathematics, and her class almost through geometry, was planning to go into trigonometry.

The discipline of the school was not unduly strict, yet after the opening, girls were not expected to speak to one another without special permission. In this matter they were put rather on their honor, for no special punishment was inflicted for disobedience. A word of disapprobation was usually the most severe reproof, although, in rare cases, girls had been kept after school. Nora, whose intentions were always good, was, of the four friends whom we have been observing, the most likely to break some of the unwritten laws of the school. She always saw the funny side of things, and it was very hard for her to keep still when she wished to share her fun with somebody else. Belle was no more scrupulous than Nora about observing rules, but she could whisper to her neighbor in a quiet way without attracting attention. Edith was really a conscientious, painstaking girl. On this account some of those who did not know her well called her a "bore." Brenda was good or bad by fits and starts. Sometimes for a week she devoted herself to her lessons. She would then put her finger to her lips when Nora, in passing her desk, bent over her to tell her some bit of news. She would pretend not to understand when Belle laid a small piece of folded paper on her desk, and she would keep her eyes fixed on her books when any other girl tried to distract her attention. To-day, however, it was different. In the first place she did not know her lesson very well and did not feel like studying. In the half-hour in which she was supposed to be doing her Latin exercise her mind constantly wandered, and she could not help seeing that Belle was anxious to tell her something. At length the little wad of paper fell on her desk.

"The tableaux were perfectly splendid! You ought to have been there."

Brenda nodded sadly. Surely this was not kind of Belle, who knew that only stern necessity had kept her at home.

"I suppose the tableaux will be as good to-night," and a second note fell on Brenda's desk, "but there won't be half as many people you know. Everybody was there last night. Shall you take Julia?"

Again Brenda nodded, but by this time she was growing impatient. Leaning forward toward Belle's desk, "Keep still, can't you, Belle," she exclaimed in a voice intended to be a whisper. Unfortunately her voice was louder than she thought, and she was recalled to herself by Miss Crawdon's voice, "Be careful, Brenda," and Brenda applied herself to her books until the hour arrived for the Latin lesson.

At recess Belle, pretending not to see Brenda, joined two of the older girls and walked with them for the half hour, while Brenda and Nora and Edith sat on the steps.

"Why didn't you know your Latin lesson?" asked Brenda of Edith. "I never knew you to stumble so, and you couldn't give a single rule."

"Well, you know I didn't study yesterday afternoon. I meant to, but it was too lovely to go in the house, and then last evening I went to the tableaux. It seemed hard to have to stay home to study though I suppose I should have. You didn't know your own lesson very well, Brenda, although you stayed home all the evening."

"But, you see, I had company——"

"You'll find it hard to do your lessons if you make company of Julia. Isn't she coming to school too?"

"Oh, I guess so. Won't it be hateful to have her in the class above us?"

"Perhaps she won't be. Didn't you say she hadn't been at school much?"

"Oh, girls who have studied at home always think they know more than any one else. Oh, there, there!" and Brenda paused in her speech as a little child playing on the opposite sidewalk ran out into the street in front of the very wheels of a passing wagon. For a moment all held their breath, then Nora with a leap and a run was down the steps and in the street. Before the child realized its own danger she had snatched it from in front of the horses, and had dragged it to the sidewalk. The teamster, a rather stupid-looking man, had dismounted from his place.

"Waal, now, the child ain't hurt, I guess," he said to the girl, "I pulled up as soon as I heard you holler, but it was such a little mite of a thing that I couldn't hardly see it."

"Oh, it wasn't your fault," Brenda and Edith exclaimed. "It ran out so quickly, but if you hadn't stopped your horses, it might have been killed."

After assuring himself that the child was not really hurt, the teamster went on, the child himself, surrounded by a group of curious girls, clung closely to Nora's hand—a forlorn little thing—with bare feet and a torn pinafore. The mud spattered over his face did not show very distinctly on his dark skin. One small hand he had thrust into his eye, and behind it the tears were slowly trickling down. Nora held the other hand, and the child clung to her as if never intending to let go.

"What's your name, little boy?" cried one of the girls.

The child only sobbed.

"Here, Amy, give him a piece of your banana. He looks like an Italian fruit-seller's child. He'll eat a banana."

But the little boy was not to be tempted.

Just then the noon bell sounded from the schoolroom.

"There, Nora, let him go, he'll find his way home," suggested one of the girls.

"Oh, no, I'm sure he's hurt. Where do you live, little boy?"

Still no reply. The other girls went back into school, while Nora walked irresolutely toward the door, holding the child's hand. As she stood at the foot of the steps wondering what to do, Miss Crawdon appeared at the door with Brenda and Edith who had hurried to tell her about the child.

"Is the little fellow hurt?" she asked with interest.

"Not really hurt, perhaps, but awfully frightened, and I'm sure he doesn't live anywhere around here. I don't want to leave him when I go into school, what shall I do?"

"Don't look so distressed, Nora," said Miss Crawdon smiling. "I'm not sure myself what is best." Then, after a moment's reflection, "You may send him down to the basement with the janitor, and later I will see what can be done."

So Nora, saying all the reassuring things that she could to the child, left him with the janitor, Mr. Brown, although this separation was accompanied with loud cries and shrieks on the part of the little boy.

It was very hard for Nora and the others to remain perfectly quiet during the hour and a half that remained of school. They were anxious to exchange questions about the child, to speculate about his home, and I am sure that the little boy was more in the thoughts of Brenda, Edith, and Nora than their lessons.

Belle had missed the excitement of the morning, for at the moment of the accident she and the two older girls whom she had joined, were out of sight of the school walking in another street.

She had returned to the schoolroom hardly half a minute before the end of recess, when there was really no time to ask a question. She did not dare to ask a question of Brenda, who still wore an unamiable expression.

When half-past one came, however, Brenda and Belle forgot their little disagreement, and hastened after Nora to learn what she was going to do with her protégé.

"Now, I'll tell you girls, just what I'm going to do. Miss Crawdon says it will be all right. Brenda and I are going with Mrs. Brown to see where Manuel lives—we have found out that his name is Manuel. We can get some luncheon here, and please, please, stop at my house, Belle, and tell my mother, and you, Edith, at Brenda's."

"Why don't you let Mrs. Brown go alone?"

"Oh, it will be so much more fun to go too."

"You can't find his house."

"Oh, yes; it will be somewhere down Hanover Street. Mrs. Brown knows. If we take him there, he'll lead us on. Oh, it will be great fun."

"I don't believe your mother would like you to go without letting her know."

"Well, I just have to go. I'm sure she won't care."

Though Nora was so confident, Brenda had some misgivings. She knew that she really ought to be at home, but the temptation to go with Nora was too strong to resist.

So, soon after two o'clock the strange procession began its march toward Hanover Street, Manuel walking between Nora and Brenda, while Mrs. Brown brought up the rear. Manuel was still silent.

"If he were a girl he'd talk more," said Nora.

Manuel showed very little interest in the whole proceeding. In fact he seemed so tired that Mrs. Brown would have carried him had he not resisted her efforts to take him in her arms.

IV

A CLUB MEETING

The strange procession had not gone very far when Nora heard some one behind calling her name. It was Miss Crawdon, who, as Nora turned around, signalled her to stop.

"Oh, Brenda, Miss Crawdon wishes to speak to us."

In a moment their teacher had overtaken them.

"I must reconsider my promise to you, or at least, Nora, you partly misunderstood what I said. It will not do at all for you to go home with this little boy. Your mother would blame me very much."

"Oh, Miss Crawdon," pouted Brenda. Nora, too, showed her disappointment.

"Now, Brenda, consider what it means. In the first place it is uncertain whether or not you could find his home. In the second place you might have to go into some dirty street or alley. With your mother's consent I should have nothing to say, but as it is——"

"Well, can't we go as far as Scollay Square? We could get a car there and go straight home."

Miss Crawdon hesitated a moment.

"As it happens," she replied, "I have to go in that direction myself. We will walk together, and I will see you safely on your car. Mrs. Brown and Manuel may lead the way."

"Isn't he cunning!" exclaimed Brenda, as the little boy looked over his shoulder at the girls, with one little hand doubled up against his eye, and his other clutching Mrs. Brown's skirt.

"I wish he would talk to us," responded Nora. "Where do you live, little boy?" Manuel smiled knowingly. "There," he said, waving his hand indefinitely toward the Square, across which the electric cars were whizzing.

"Oh, no," cried Nora, "nobody lives there; there are shops and a hotel, and——"

"Birdies, birdies, there," cried Manuel.

Even Miss Crawdon smiled as Manuel ran up to a shop window, and pounded the glass, somewhat to the dismay of the parrots exhibited there in their cages.

"Well, he seems to know this shop," said Mrs. Brown. "We might wait here for a minute."

At the other side of the shop around the corner was a doorway in which sat a woman with a basket of fruit for sale. Manuel himself was the first to catch sight of her, and rushing forward with a flying leap, he almost knocked her basket over. The little boy had found his tongue, and chattering like a magpie, he pointed toward the ladies. The woman, rising from the step on which she had been sitting, came toward the little group. In broken English she explained that Manuel was her youngest boy, and that sometimes she let him go with her on her round of fruit-selling. Lately she had had her stand near this bird store, and in some way on this particular day, Manuel had wandered away from her.

"You must have been worried," said Nora.

"Oh, no," she answered philosophically; "me thought him gone home."

Then Brenda, who had hitherto kept silent, broke in with a graphic account of the fate Manuel had escaped through Nora's bravery. The mother probably only half comprehending the young girl's rapid flow of words, smiled and showed her white teeth. "T'ank you, t'ank you," she said. "You come and see him some day," she added, in a general invitation to the group.

"Come, girls, we must hasten," said Miss Crawdon. "Mrs. Brown will take down Manuel's address. Then, if your mothers are willing, you may go to see him some day."

Rather reluctantly Nora and Brenda bade good-bye to black-eyed Manuel and his mother. They gave Mrs. Brown many injunctions to make no mistake about his house and street. On Saturday they both hoped to be able to go to see him.

To them the whole thing presented the aspect of an adventure.

"I never spoke to a foreigner before in Boston, did you?" said Nora, "I mean except French teachers," she added.

"No, not a poor foreigner," responded Brenda. "Wasn't that woman picturesque, with her shawl over her head?"

As they drew near home both girls began to feel a little doubtful as to the wisdom of what they had done.

"Well, your mother never scolds," said Brenda, as she bade good-bye to Nora at the door of the latter.

"Why, yours doesn't either," exclaimed Nora.

"Oh, you don't know," and Brenda shook her head. "There's Julia now——"

"Nonsense," laughed Nora, running up the steps. "Good-bye, now. I'm coming to see Julia this afternoon. You know I expect to like her."

"Your lunch is waiting, Miss Brenda," said the maid as Brenda started up the front stairs toward her room.

"Oh, I've had my luncheon," replied Brenda. "You don't think I'd wait until this time."

"Brenda," called her mother from the library, "it's half-past three. Where have you been since school?"

"Oh, dear!" grumbled Brenda to herself. "I don't see why I have to give an account of every step I take. I'll be down in a minute," she called out, as she continued her way upstairs. When she descended to the library, she hastened forward with a polite "Good-afternoon" to Julia, who was seated before the fire with a book in her lap.

"Julia has been reading to me," said her mother.

"We have had a very pleasant hour," added Julia.

"But tell me where you have been," said Brenda's mother. "You know that it is a rule that you should come directly home——"

Brenda tossed her head.

"Oh, I asked Belle to come and tell you."

"She may have left word that you were not coming, I think that Thomas gave me some message, but let us hear where you have been."

Mrs. Barlow spoke pleasantly, for she knew by the cloud on Brenda's face that there might be a storm if for the present she said too much about her absence from luncheon.

"Yes," added Julia, "do tell us where you have been. I have an idea that you have had an adventure."

"How could you guess?" exclaimed Brenda, and then, with the ice broken by these words of Julia's, she gave her mother an animated account of Nora's bravery, Manuel's beauty and the fruit-woman's picturesqueness.

Mrs. Barlow and Julia were interested. Brenda had a graphic way of telling a story, and the events of the morning lost nothing by her telling. But Mrs. Barlow shook her head when Brenda spoke of visiting Manuel in his home.

"It might not be at all a proper place," she said, "and besides, Manuel's mother may not care to have strangers visit her. Poor people sometimes are very sensitive about such things."

Before Brenda had time to argue this point with her mother, the portière was pushed aside and Belle and Edith came into the room. Julia rose to shake hands with Belle, while Edith with a very sweet smile, stepping toward her, said:

"I am glad to see you. I am one of 'the Four.' Brenda's told you about us. I am Edith."

Julia felt strongly drawn to the pleasant-faced girl. She liked her better than Belle, although on the two occasions of their meeting the latter had been markedly polite to her.

"Yes, we're all here now except Nora. We ought to be ready to give her a serenade, or something like that when she comes. She's really a kind of a heroine, isn't she?"

"Oh, nonsense, Edith," said Belle. "She did not actually do so very much. Those horses were not running away, and a little paddy like that child has as many lives as a cat."

"He isn't a paddy," interrupted Brenda, "but a Portuguese,—a dear little Portuguese—and Nora was very brave. It's just like you, Belle, to think that a thing isn't of any account unless you have had something to do with it."

Belle was silent. In the presence of a stranger she never forgot her good manners, and Julia was still sufficiently a stranger to act as a check on the sharp reply which otherwise might have risen to her lips. Edith now came in as a peacemaker.

"Well, it was great fun to have anything out of the ordinary happen at school. You can't imagine," turning to Julia, "how stupid it is to have things go on in the same way day after day. Last week there was a fire alarm about two blocks away, and just think, the engines passed scarcely five minutes after recess was over, and Miss Crawdon wouldn't let us run out to see where the fire was."

"Naturally not," said Mrs. Barlow, as she left the room, adding, as she passed out,

"By the time you are ready, Julia, the carriage will be here."

"Yes, Aunt Anna," answered Julia, and she, too, after a few pleasant words with Edith, excused herself with the explanation that her aunt had promised to accompany her to do some important errands down town.

"Come upstairs with me," said Brenda, with an air of relief, as Julia left. "There's Nora, now, I know her ring of the bell."

Nora soon joined the other three in Brenda's pretty bedroom.

"Here we are, all four together again," exclaimed Brenda, as she threw herself down on the chintz-covered sofa. "It's so much pleasanter not to have any strangers about."

"Do you call your cousin a stranger?" asked Nora.

"Why, yes, any one can see that she's terribly serious, and that she won't take a bit of interest in the things we do."

"Aren't you going to ask her to join the Four Club?"

"Well, then it wouldn't be a Four Club. Besides five is a horrid number. You never can plan things together when there are five."

"But you can't leave her out."

"I don't see why not. She'll have other things to do in the afternoon—like to-day. We needn't tell her about the Club at all, need we?"

Edith and Nora, to whom Brenda seemed to appeal, said nothing. Belle was looking out of the window, and though she usually would have agreed with Brenda, they had lately had so many little disagreements, that she would not gratify her friend by assenting to her words.

Brenda, however, perceiving that her views were not shared by the other three girls, decided to avoid discussing Julia any further.

"Let us come to order like a club," she exclaimed, "and decide what we shall work for this winter."

In the preceding spring the four friends had decided that it would be very interesting to give their occasional meetings a club form. Instead of passing their afternoons in mere idle talk, they would have some object. They would all do fancy work, and perhaps have a sale in the spring for some charity. Each of the girls had already spent all her spare pocket-money on materials for needlework, although as yet they had made but little headway in their work. Nor had they decided for what object the sale should be held.

"It's a good deal like counting your chickens before they are hatched," Mrs. Barlow had said when Brenda consulted her on the subject. "It would be better to wait until you have enough work for a sale, before deciding what to do with your money."

In her heart Mrs. Barlow doubted that the girls would make enough money to be worth giving to any institution. She doubted even that they would persevere in their work, and have a sale. Brenda, herself, was too apt to begin with enthusiasm some undertaking which after a while she would let languish until it came to nothing. In this case Brenda was indignant at her mother's want of faith.

"Now you know that I'm older than I used to be, and I'm perfectly in earnest about wanting an object to work for."

"Very well, Brenda," said Mrs. Barlow smiling, "I certainly will not interfere, only you must give me time to think of a beneficiary for your money."

Now if the girls had started with a definite object to work for, their club meetings would have lost much of their interest. As it was, more than half their time was spent in earnest discussions of the merit of different institutions. Edith thought that a hospital was the noblest object of charity, although the others objected that the City or the State usually looked after hospitals. Nora hoped their money would be given to some orphan asylum, or a home for old persons, Belle believed that there was nothing so worthy as the Institution for the Blind, and Brenda changed her point of view from week to week.

"What are we to work for this week, Brenda?" asked Belle, somewhat derisively, as she opened her sewing-bag.

"Oh, I don't know. We're not working for anything in particular." Then, as her eye met Nora's, a new idea came.

"Oh, I'll tell you what, girls,—let us work for—Manuel!"

"'Oh, I'll tell you what, girls,—let us work for—Manuel!'"

V

MISS CRAWDON'S SCHOOL

A girl's first day at a new school is very trying to her. The scrutiny which two or three dozen pairs of sharp young eyes give her is hard to bear. This ordeal is often more dreaded by a girl than many of the important events of her later years. Now Julia, although she was to go to school in her cousin Brenda's company, looked forward to her first day with considerable anxiety. In the first place she was naturally shy, and in the second place she had never regularly attended school. For the most part her lessons had been given her by her father. But at times when they had stayed long enough in some place to make this possible, she had had special instruction from private teachers. Her father had been very fond of books and had bought many expressly for Julia's benefit. She was, therefore, much better read than most girls of her age. Her education, too, was ahead of that of the average girl of sixteen. Of this fact Julia herself was unaware. She fancied that because she had gone to school so little, she would be found far behind her cousin Brenda and Brenda's friends. Before going to school she had had an informal talk with Miss Crawdon, in which she had revealed more to the keen mind of the latter than she had suspected. For Miss Crawdon never wasted words, and she did not tell the young girl that in some studies she was far ahead of many of her pupils of the same age. The teacher's questions had been far-reaching, and she felt pleased at the prospect of having among her pupils one evidently so fond of books as Julia.

The young girl, on the contrary, on the way to school with her cousin, expressed to the latter her fear at the prospect before her.

"Oh, you needn't worry," said Brenda, more patronizingly than she really intended, "Miss Crawdon won't be hard with you, she knows you haven't been at school much, and even if you have to start in one of the lower classes, you'll probably be able to push on rather quickly."

But even this did not reassure Julia. She was thinking less of her standing in the classes than of the reception she should meet from the girls. It was by no means comforting to feel the many strange eyes that followed her as she walked up the stairs with Brenda to enter the main schoolroom. Miss Crawdon was busy in another room, and Brenda who always had a great many things on her mind, rushed off to speak to one of the girls, leaving Julia alone near the door. There were perhaps a dozen girls standing about in little groups of three or four. They did not mean to be unkind, but when they saw Julia, they not only glanced curiously toward her, but for the time ceased their conversation. When they began to talk again it was not in the loud tone they had used before, and Julia would have been less than human if she had not received the impression that they were talking about her. Every one knows how uncomfortable it is for a girl to feel that she is in the presence of people who are making comments upon her. As a matter of fact what they said to one another was almost harmless.

"Is she Brenda Barlow's cousin?"

"What is she in mourning for?"

"How old is she?"

"Do you suppose she is coming here to school?"

This was the kind of question exchanged by the girls, with here and there a less good-natured comment.

"I don't call her so very pretty."

"She doesn't look like Brenda."

"Wouldn't you say that dress was made in the year one. I never saw such sleeves."

Unluckily the girl who made this last remark was standing rather nearer Julia than she had realized. It happened that Julia herself, who usually cared little for fashion, was sensitive about these very sleeves. They had been made a little smaller than the prevailing mode required by a dressmaker whom Julia had employed in a spirit of kindness without regard to her skill. She had not remembered when dressing that this was to be her first day at school. When she did recall this fact she had not thought it worth while to change her gown. She flushed a little when she overheard the criticism, and walked farther away from the groups toward Miss Crawdon's desk.

As she stood there looking more serious than usual, she was more than pleased to hear Nora's well-known voice exclaiming,

"Why, Julia, are you here all alone? Where's Brenda? Dear me, is this really your first day of school?"

Julia smiled. "I can't answer all your questions at once, but I don't know where Brenda is, and this is to be my first day of school."

"Is that why you look so mournful? Now we're not such a bad lot. Come, let me introduce you to some of your companions in misery." Then before Julia could object, she found herself receiving introductions to most of the girls in the room, even to the very one whose criticism had annoyed her. She was a thin girl with light hair and eyes and eyelashes. Her chin was long and her face was somewhat freckled.

"This is Brenda Barlow's cousin Julia," said Nora, pleasantly.

"Yes, I thought you were Brenda's cousin," said the light-haired girl turning toward Julia. "Brenda's been dreading your coming to school."

Julia flushed as any girl might at a remark of this kind, even while she realized the unkindness of the speech.

"Nonsense, Frances," said quick-witted Nora, "I'm sure you never heard Brenda say anything so disagreeable."

But the light-haired girl had turned away. She was in the habit of making thoughtless remarks without caring whom they hit. Nora gave Julia's hand a gentle squeeze. "Brenda's just as glad as I am that you're coming to school," she whispered to Julia. But Julia shook her head, half sadly. She had already begun to see some of her cousin's peculiarities.

By this time many girls were rushing in from the dressing-rooms laughing and chattering as if they must say as much as possible before school began.

A few curious eyes were turned toward Julia, but most of the girls were so absorbed in their own affairs that they took no notice of the tall slender stranger in her black dress.

When Miss Crawdon returned to the room she welcomed Julia very cordially.

"I have arranged a seat for you here at the side near me," she said. "I had to have an extra desk brought in as there was no vacant place. But I dare say that you will not mind being by yourself here."

The seat to which Miss Crawdon pointed was in a little alcove at one side of her desk. It was so placed that it commanded a view of all the other desks in the room, yet it was not as conspicuous from the other desks as it seemed to poor Julia. When she took her seat she felt as if every one was looking at her. Whereas, in fact, only the girls in the very front rows could see her plainly. Between Miss Crawdon's desk and the front seat there was a row of settees where those girls who formed Miss Crawdon's special classes, sat during recitation. There were other class-rooms in various parts of the house, but the more advanced girls recited either to Miss Crawdon or to teachers in the small adjoining room.

Although Julia was less conspicuous than she imagined, it was not long before the whole school realized that a new girl had arrived. Most of them were too polite to show any surprise, but as each class filed through the room on its way to the recitation-room, many curious glances were thrown in her direction.

Miss Crawdon had told Julia that she would require no regular work from her that day.

"Perhaps you would like to look over this history," she had added, giving her a book, "and after recess, you may like to join the class. By listening to the other classes this morning you will get an idea of the kind of work I expect."

So Julia divided the two hours before recess between listening to the recitations and glancing over the history. It happened to be a history of France, and the special chapter was one dealing with the reign of Louis XIV. Julia paid much less attention to the book than she did to the girls who were reciting. It was all so new to her, for it was really true that she had never been in a school before. She admired the skill with which Miss Crawdon asked questions, and she wondered if she would ever be able to give replies herself, as clear as those of some of the girls. Yet not all the girls, she observed, knew their lesson, and some of them showed great cleverness in concealing—or trying to conceal this ignorance from Miss Crawdon. The latter was unusually proficient in reading girls, and she generally recognized the evasive answer that was intended to conceal lack of knowledge. The second class of the morning was one in English history, the period, the beginning of the reign of Mary. Julia had been engaged with her own book, but she looked up to hear Miss Crawdon saying, "So Mary succeeded one of the Princes murdered in the tower, at least I understood you to say Edward V."

"Yes," answered a voice which Julia recognized as that of Brenda's friend Belle, "yes, she succeeded her brother, the murdered prince, who had been beheaded by Katharine of Arragon."

Miss Crawdon did not smile, and Belle could not see the look of surprise on the faces of some of her classmates. But unfortunately she could see Julia's face and the involuntary smile on the latter's lips. She turned very red, and while Miss Crawdon proceeded to set her right, she registered a vow of dislike against that "prig of a Julia" who evidently knew more history than she did. Julia, too, caught the disagreeable look that flashed from Belle's eyes, and she greatly regretted that smile. Belle was one of those girls who seldom study a lesson thoroughly. She always had vague general ideas of the topic under consideration, gained by a rapid survey of the pages assigned for a lesson. When she could do so unobserved, sometimes during recitation she would look between the covers of her book to refresh her lagging memory. Nora and Edith and Brenda were also in the class with her, and sometimes one or the other of them would prompt her to save her from disgrace. Nora occasionally had pangs of conscience, and announced that she considered looking in a book or prompting, dishonorable. But sometimes she yielded to Belle's signals for help over a hard place. Belle did not often signal, for she relied as a general thing on her own fluency of language to conceal her lack of knowledge. Miss Crawdon, however, had what Belle called an aggravating way of making her repeat her words until her mistakes were displayed in all their nakedness to the rest of the class.

"It's bad enough," she said to a group surrounding her at recess. "It's bad enough to have Miss Crawdon always down on one, but really I can't stand it if Julia is to sit where she can watch everything I do when I'm reciting to Miss Crawdon. I shouldn't think that you girls would like it either," she concluded.

"Oh, we're not afraid; we generally know our lessons," answered Frances Pounder, the girl whose careless remark had hurt Julia's feelings earlier in the day.

"Well, it doesn't matter whether you know your lessons or not, you can see for yourself that it's very funny for Miss Crawdon to put any girl in so conspicuous a place, right beside her, almost. I hate favoritism."

"Why, how you talk, Belle. This cousin of Brenda's hasn't been in school a day yet, and you talk of favoritism."

"Well, why shouldn't she have been in the history class with us? She told me she was going to have French history with the older girls. Just think of it, she's only a little older than we, and she's going to recite with girls nearly eighteen."

"She isn't so very pretty, is she?" said another girl, and so a conversation went on which luckily Julia could not hear. She spent the recess walking up and down with Nora, who was rapidly becoming her most intimate friend.

VI

MISUNDERSTANDINGS

Little by little Julia accustomed herself to the routine of school. At first it was much harder for her than any one suspected. Even after she had become fairly well acquainted with the girls in her classes, she dreaded each recitation. It was no easy task to put her knowledge into the definite form needed in answering questions. She had much more general information than many of her classmates, but nearly all were better skilled in reciting lessons. Although in history, Latin and literature she was two classes ahead of Brenda and the three other inseparables, she was with all but Edith in mathematics, and, rather to Brenda's delight, a class below them in French. Julia's father had been much less interested in modern than in ancient languages, and Julia had had limited opportunities for learning French. Belle, on the contrary, was a really fine French scholar. She was fonder, indeed, of introducing French words and phrases into her conversation than should have been the case with a girl who really understood the French language. Edith excelled in mathematics, Nora, strange to say, Nora, who was so careless about most of her lessons, had a real gift for English composition. Brenda did well in all her studies "by fits and starts," as the girls said. She had fine powers, her teachers often told her, which she seldom exerted to the utmost. But Brenda and her friends formed only a small part of the school, and Julia soon found that in every class she had one or two competitors whose proficiency spurred her on.

To be perfectly frank, however, it must be said that the majority of Miss Crawdon's girls were not hard workers. Miss Crawdon, herself, often felt greatly discouraged that girls with the opportunities of most of her pupils, should appreciate these opportunities so little. With most of them attending school was a mere duty, a way in which several months of each year must be spent until they should "come out." Miss Crawdon tried in vain to arouse in most of them something more like a passing interest in their work. Occasionally she found a spark of earnestness in one of her pupils which she was able to fan into ambition. But more often she had to give up the attempt to induce a bright girl to become a genuine student. There were too many distractions out of school, and parents were apt to be slow in seconding her efforts. Miss Crawdon was pleased, therefore, to find in Julia a girl who loved study and who was inclined to persevere.

One day Brenda came home from school in a state of considerable excitement.

"What do you think, mamma, Julia is going to study Greek! Did you ever hear of such a thing?"

"Why shouldn't Julia study Greek?" said her mother. "Why are you so excited about it?"

"Oh, it's so foolish. No girl at Miss Crawdon's ever studied Greek before. Julia says she's going to college, is she? Oh, dear, I think it's horrid."

"Why, Brenda, really——"

"Well, it makes me so conspicuous."

"How can that be?"

"Why every one will point me out and say, 'Oh it's her cousin who studies Greek.' It sounds so strong-minded to talk of going to college. The next thing she'll want to be a teacher."

"It seems to me you are very unreasonable, Brenda. You ought to be glad that your cousin is so ambitious. I only wish that you were half as fond of study."

"There, that's it. I knew there'd be comparisons. Oh, dear! It never was so before Julia came."

"Daughter," said Mr. Barlow from behind his paper. Brenda trembled, for her father's "Daughter" was generally the introduction to a lecture. "Daughter, I fear that you are jealous."

Brenda shook her head. "Oh, papa!"

"Yes, Brenda, I have noticed in several ways that you are less kind to Julia than you should be. How does it happen that you and she never start off to school together?"

"Brenda is never ready when Julia is," said Mrs. Barlow.

"Ah, Brenda, your habit of tardiness is a very bad one."

"I'm hardly ever late at school. Belle and I get there a full minute before the bell rings."

"That may be, but it would be better if you and Julia started together."

"She does not have to go alone. Nora is generally with her."

"Ah, Brenda, the point I am trying to make is this; you do not spend nearly as much time with your cousin as I had hoped you would, and you are too ready to find fault with what she does!"

"You always blame me, and you never find any fault with Julia. Why didn't she tell me that she was going to study Greek? The girls all asked me to-day if I knew about it, and I had to say that I hadn't heard a word."

"You and Belle have been very much occupied with your own affairs this week. Julia consulted us about her plans and——"

"Well, is she going to college?" interrupted Brenda.

"I cannot say positively," smiled Mrs. Barlow. "It rests with Julia herself."

"I never saw anything like it," pouted Brenda. "Julia isn't two years older than I, and you let her do whatever she wants to. Oh, dear!" And Brenda pushed aside the portière and left the room.

"That is just what I feared for Brenda," said Mr. Barlow. "Julia's coming makes her even a little more suspicious than she was before. She constantly has the idea that something of importance has been concealed from her which she ought to know."

"Yes," replied Mrs. Barlow, "I am afraid that Brenda is hopelessly spoiled. We did not realize the danger when she was little. The other two girls were so different."

"It would not surprise me," responded Mr. Barlow, "if after all some change should come to Brenda's point of view from having to consider her cousin more or less."

"If only she would consider her," sighed Mrs. Barlow.

If Julia felt at all slighted by Brenda, she did not say so. Indeed she was too well occupied with her lessons and her music to be disturbed by trivial things. What her object was in studying Greek she did not disclose fully to any one, but she studied diligently the difficult declensions and conjugations. The serious looking man with eyeglasses who came to the school three times a week, was an object of much interest to most of the girls.

"Doesn't he look learned? Oh, Julia, I should think that you would be frightened to death," said Edith. But Julia smiled.

"I wish myself that Greek were just a little easier. I've got to the verbs and it seems to me I never shall know them."

"I don't wonder," responded Edith. "I don't see how you ever learn it,—all those queer letters and marks and things. Well, I should feel just as though I were standing on my head if I tried to study Greek."

Edith had no vanity about herself, at least in the matter of lessons. Her special talent was for drawing and mathematics but although she was conscientious about her school work, she rarely distinguished herself in her recitations. Like Nora, she had begun to have a great admiration for Julia. The latter shook her head when Edith spoke of the difficulty she had in learning Greek.

"It's like everything else," she said, "you can learn it if you make up your mind to try hard enough."

"I wish that had been the way with my German, for I really did try. Papa is disappointed, because he wanted me to speak by the time we go to Europe again."

"Then why don't you persevere? It would please him and it would do you good. If I were you I would take it up now."

"Well, perhaps I will after Christmas. Miss Crawdon won't let us make any changes until then."

As Edith watched Julia's diligence and perseverance she really became ashamed of her own rather indolent way of treating her lessons.

When Nora or Brenda came for her to go to walk early on some bright October afternoon she was very apt to say, "Oh, I cannot go now, I must finish studying."

"Well, Edith, I never knew anything so funny," Brenda exclaimed one day when she and Belle had vainly tried to persuade Edith to walk with them over the mill-dam. "You never used to make such excuses and I consider it a perfect waste of time myself to spend such a lovely afternoon studying. I should think your mother'd want you to have some exercise."

"Oh, I shall have plenty this afternoon. I am going to the gymnasium for an hour with Julia, and that will answer for to-day. We took a walk before school this morning."

"You and Nora are too provoking, Edith," exclaimed Brenda rather pettishly. "Ever since Julia came you seem to prefer spending your time with her. You never used to be such a book-worm."

"Well, I'm trying to make up for lost time. I wish that I could accomplish as much as Julia."

"Oh—Julia, Julia, I'm sick and tired of the name," exclaimed Belle. "Why in the world does she study so much, Brenda?"

"I'm sure I don't know."

"You ought to—you're her cousin. I believe myself that she's going to be a teacher."

"Belle, it is not nice in you to say that," interposed Edith.

"Why isn't it nice to be a teacher. I thought that you liked them more than anything else. I am sure that Julia does."

"I dare say she does, but it doesn't follow that she's going to be a teacher herself."

"Oh, anybody can tell that she's a poor relation—isn't she, Brenda? Just see how plainly she dresses, and working so to get into college. I think that your mother and father are very good to give her a home."

Now all this was very presumptuous on Belle's part, but she spoke so pleasantly and smiled so sweetly at Brenda as she talked that the latter, though a little irritated, never thought of taking offence at her. But Belle's words had sunk deeper even than she had intended. Brenda had a certain kind of pride which was easily touched. She felt that in some way it was a source of discredit to her to have a cousin who might be a teacher. For in what other way could she interpret Julia's intention of studying Greek.

Julia, unconscious of Brenda's feeling, went on quietly without heeding the disagreeable little remarks that sometimes were made in her hearing by Brenda. Belle was as polite and agreeable toward Julia as to others whom she liked better. For it was a kind of unspoken policy of Belle's to be apparently friendly with all girls of whom she was likely to see much. If accused of this failing she would not have admitted that she was two-faced. She merely liked to be popular, and if she sometimes made ill-natured remarks about a third person, she trusted to the discretion of those to whom she talked. She did not realize that in time she might come to be regarded as thoroughly insincere. She had not measured the relative advantages of "To Be" and "To Seem."

VII

VISITING MANUEL

Two or three weeks after their adventure with Manuel passed before Brenda and Nora were able to visit him. They talked several times of going, but something always interfered. Sometimes it was the weather, sometimes it was another engagement, more often they could not go because they had no one to accompany them. For it was evident that two young girls could not go alone to the North End. At length one morning one of the under teachers in the school offered to go with them that very afternoon. She had overheard them at recess expressing their sorrow that they could not go alone.

"Really," pouted Brenda, "I think that mamma is very mean. We could go as well as not by ourselves, and why we should have to wait for her or some older person to go with us I cannot see."