In Barbary : Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco and the Sahara

E. Alexander Powell

IN BARBARY

Books by E. ALEXANDER POWELL

TRAVEL AND WORLD POLITICS

- In Barbary

- Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, and the Sahara

- Beyond the Utmost Purple Rim

- Abyssinia, Somaliland, and Madagascar

- The Map That Is Half Unrolled

- Tanganyika Territory and the Congo

- The Last Frontier

- Politics and Travel in Africa

- The End of the Trail

- The Far West From Mexico To Alaska

- New Frontiers of Freedom

- From the Alps To the Ægean

- Where the Strange Trails Go Down

- Malaysia and Siam

- Asia at the Crossroads

- Japan, China, and the Philippines

- By Camel and Car to the Peacock Throne

- Syria, Arabia, Iraq, and Persia

- The Struggle for Power in Moslem Asia

- Politics in the near and Middle East

HISTORY

- Gentlemen Rovers

- American History

- The Road to Glory

- American History

- Forgotten Heroes

- American History

THE GREAT WAR

- Fighting in Flanders

- The Campaign in Belgium, 1914

- Vive La France!

- The Campaign in France, 1915

- Italy at War

- The Campaign in Italy, 1916

- Brothers in Arms

- America Enters the Great War

- The Army Behind the Army

- America at War, 1917-18

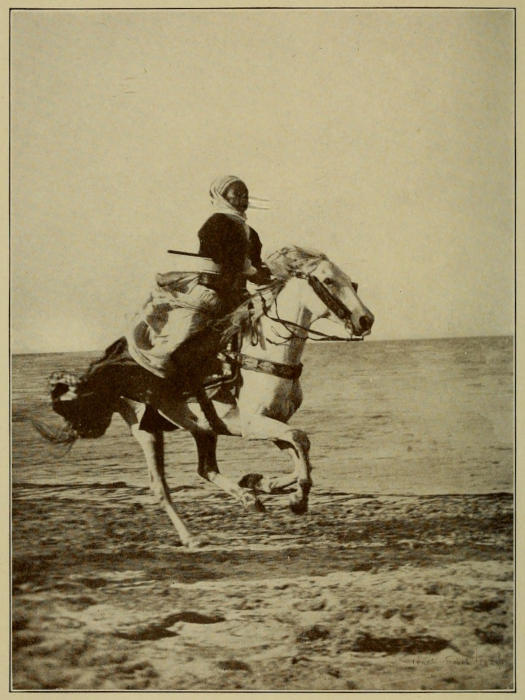

A SOLDIER OF AFRICA

There is no finer light-horseman on earth than the spahi—a cow-puncher, a Cossack, an Indian brave, and a Bedouin warrior combined

IN BARBARY

TUNISIA, ALGERIA, MOROCCO

AND THE SAHARA

BY

E. ALEXANDER POWELL

With Eighty-six Illustrations

from Photographs and Two Maps

PUBLISHED BY THE CENTURY CO.

NEW YORK LONDON

Copyright, 1926, by

The Century Co.

PRINTED IN U. S. A.

To

My Daughter

BETTIE

In memory of the days

when we rode across

the desert

FOREWORD

Unlike most of my preceding volumes, this book deals with countries which are comparatively near to home. Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco—which we know collectively as Barbary—lie at the very door of Europe; their principal ports are scarcely more than overnight from Naples, Barcelona, and Marseilles; scores of tourist steamers drop anchor in their harbors every winter, and they are visited by increasing numbers of Americans each year. Yet it is a curious fact, and one difficult to explain, that the popular misconceptions regarding these easily accessible lands are even more glaring than those in respect to far remoter regions which the white man penetrates at every risk.

The truth of the matter is that most Americans, and most Europeans too for that matter, think of Barbary in terms of the corsairs, the Garden of Allah, the dancing-girls of the Ouled-Naïl, the Foreign Legion, Raisuli and Perdicaris, the squalor and confusion of Europeanized Tangier, the Riff and Abd-el-Krim, the luxurious resort hotels of Algiers, the Street of the Perfume-Sellers in Tunis, Moroccan leather-work, camels, tiled gateways, the utterly impossible sheikhs described by Mrs. Hull and interpreted by Hollywood, and the sand-dunes so frequently pictured in the “National Geographic Magazine.” With our unfortunate propensity for generalizing, we have assumed that these high spots were typical of Barbary, thus forming a mental picture which is as fantastic as it is inaccurate.

For example, we speak of the inhabitants of North Africa as Arabs, who in reality are only a minority, the bulk of the population being composed of Berbers, the earliest known possessors of the soil, who still hold the highlands which stretch from the borders of Egypt to the shores of the Atlantic, from the sands of the Mediterranean to those of the Sahara, that vast extent of territory to which we have given their name, Barbary.

We think of the Berbers as crude and uncultured, as barbaric, bloodthirsty, and backward as were the American Indians. Yet before America was so much as heard of, they, not the Arabs or the Saracens, had raised at Granada and Seville those glorious buildings which are among the architectural triumphs of the world.

Because of their sun-tanned skins, and recalling, perhaps, the old term “blackamoor,” we assume that the Berbers are a colored race and are astounded when we are told that they are of pure Caucasian stock, racially as white as ourselves.

Because it is in Africa we take it for granted that Barbary swelters in a torrid climate, whereas it is a cold country with a hot sun. In Algeria the week after Easter I have seen snow several inches deep, and the mountains to the south of Marrákesh are topped with snow nearly the whole year round.

Most of us think of Morocco as a treeless, semi-arid, almost level land, yet it has vast forests of oak and pine, several rivers comparable with the Thames or the Hudson, and in the spring its prairies and hill-slopes are carpeted with countless varieties of wild flowers. Far from being level, it is a highly mountainous country; the Moroccan Atlas has a greater average height than the Alps, and at least one of its peaks is higher than any mountain in the United States outside of Alaska.

We ourselves went to war in ’98 to end the intolerable rule of Spain in the Western Hemisphere, yet the propaganda skilfully disseminated from Madrid and Paris has blinded us to the fact that Abd-el-Krim and his mountaineers of the Riff were fighting for precisely the same reason for which the Cubans fought—to throw off the yoke of Spanish tyranny and cruelty.

Because in the geographies of our school-days large portions of North Africa were painted a speckled yellow, and because of the pictures of sand-dunes reproduced in certain magazines, we habitually picture the Sahara as a trackless waste of orange sand, on which grows no living thing, little realizing that it is broken by mile-high mountain ranges and dotted with oases, some of them as large as a New England State, which support thousands of inhabitants and millions of date-palms.

Basing our idea on motion-pictures made in Hollywood, and on novels of the desert school of fiction, we imagine sheikhs—and for heaven’s sake pronounce it shakes instead of sheeks!—as romantic, picturesque, debonair gentlemen with chivalrous instincts and charming manners, whereas candor compels me to assert that most of them are blackguardly ruffians, lustful, cruel, vindictive, ignorant, debased, as filthy of mind as of body.

We have long accepted as gospel the assertion that the British are the only really successful colonizers in the world; the French colonial we have pictured as a miserable being who spends his days in a hammock, sipping absinthe, reading “La Vie Parisienne,” and counting the hours until he can return to la belle France. Yet, in the space of a single generation, these miserable and inefficient beings have in Africa alone conquered and consolidated and civilized a colonial empire greater in area than the United States and all of its possessions put together.

And, finally, we cling to the delusion that Barbary, though doubtless colorful and picturesque, is deficient in monuments of historical or architectural interest, and that the facilities provided for the comfort of the traveler are limited and somewhat crude. Let me remark, by way of answering this objection, that Tunisia is as thickly strewn with Roman ruins as Italy itself; that the scenery of the Grand Kabylia and the High Atlas is as impressive as any in Switzerland; that the mosques and towers and palaces of Morocco were built by the same race which raised the Alhambra and the Alcázar; that the network of motor-roads which cover Barbary compare very favorably with the best highways we have in the United States; and that the hotels which have sprung up all the way from Tunis to Marrákesh are not far removed in luxury from the great tourist hostelries of Florida and California.

Extremely misleading too have been the pictures of political conditions in North Africa as drawn by certain members of self-styled “American missions,” who have visited the country at the invitation of the government, have been dazzled by fêtes and flatteries, and have swallowed the propaganda assiduously fed them by their hosts. I yield to none in my admiration for what France has achieved in North Africa, but to assert, as have certain American visitors, that the natives are contented with French rule and would give their life’s blood to defend it is to take wholly unjustifiable liberties with the truth.

It is to correct the current misapprehensions in regard to Barbary, some of which are alluded to above, that I have written this book.

I am perfectly aware that the countries to which the following pages are devoted have been treated of many times, and that my pages contain nothing that is startling, little that is really new. But I can at least make this claim for my book, that it is the only one, so far as I am aware, which brings the whole of French North Africa, its history, peoples, customs, places of interest, resources, and politics, between two covers. During my last two or three visits to Barbary I have been struck by the lack of such a book, and I have designed this one to fill a needed want.

Though I have used my last African journey, which occupied the winter, spring, and early summer of 1925, as a thread on which to string the incidents and impressions recorded in the ensuing chapters, it should be explained that much of my information was gathered during earlier visits, dating back to the early years of the present century. Hence I am in a position to make comparisons. For it has been my great good fortune to have seen the preliminary sketches as well as the completed picture. I was in the Sahara when it was still “the Last Frontier”; I knew Morocco as it was a decade before the white helmets came.

While having no desire to trespass on the field of Messrs. Baedeker, Murray, and Cook, I have nevertheless attempted to produce a volume which will be of real service to the casual traveler by incorporating definite information as to routes, hotels, and general travel conditions and by calling to his attention places which, though not always mentioned in the guide-books, are well worth seeing. I have also sketched the natural resources of the various regions and have endeavored to acquaint my readers with the highly involved political situations which exist in all of them. It may be said, by way of criticism, that my pages are overburdened with historical matter, but without the background of the Punic settlements, the Roman, Vandal, Byzantine, and Arab invasions, and the activities of the corsairs, it is impossible to understand Barbary as it is under the French.

It may also be assumed by some that, as I was afforded numerous facilities by the French authorities, this book is a reflection of the French view. I would remind such critics that the remoter districts of North Africa are still in military occupation, forbidden to the casual traveler, and that they may be visited with the permission of the French military authorities or not at all. Though such permission was promptly granted whenever I requested it, and though French officials of all grades went out of their way to show me courtesies and extend assistance, my judgment has not been affected by the consideration I received, nor my views biased, as the following pages will testify. To much that the French have accomplished in North Africa I raise my hat in respect and admiration; of other phases of their policy I do not approve. In both cases I have spoken my mind freely. My opinions may not be worth much, but at least they are my own.

E. Alexander Powell.

Sugar Hill,

New Hampshire,

August, 1926.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The journey described in the following pages was first suggested to me by a dear and deeply lamented friend, the late Hugues Le Roux, senator of France and a noted African explorer, who had taken an active and highly helpful interest in my preceding expeditions into the Dark Continent. Through the kindness of Senator Le Roux and of his charming American wife I met at their dinner-table many persons, some of them high in the French political world, who were of immense assistance to me.

M. Albert Sarraut, then minister of the colonies, and General Nollet, at the time minister of war, placed at my disposal all the facilities of their departments of the government. M. Jean Jules Jusserand, former French ambassador to the United States; his successor at the Washington embassy, M. Berenger; the Hon. Myron T. Herrick, American ambassador to France; Christian Gross, Esq., secretary of the American embassy in Paris; M. Marcel Knecht, the famous editor and publicist; M. Joseph Perret, director of the French Government Tourist Information Office in New York; and my old friend, James Hazen Hyde, Esq., all aided me with valuable advice and letters of introduction.

In Tunisia my path was made pleasant by the French resident-general, M. Lucien Saint; in Algeria by the governor-general, M. Théodore Steeg; and in Morocco by the resident-general, Marshal Lyautey. General Vicomte de Chambrun, commanding the French troops in Fez, from whom I have always received the warmest of welcomes upon my visits to that city; General Daugan, commanding the forces in Southern Morocco; Colonel Paul Azan, commanding at Tlemcen, in Algeria; and Vicomte Louis de Trémaudan, of the civil administration at Marrákesh, were all largely responsible for the pleasure and interest of my journey by making it possible for me to visit districts not as a rule open to Europeans. It was my great good fortune to have as my guide to the ruins of Carthage the Rev. Father Delattre of the Order of the White Fathers, who is one of the foremost archæologists in the world; while Miss Sophie Denison, who has been a medical missionary in Morocco for a third of a century, was of great assistance to me in Fez. Two voyages on the S.S. La France were made delightful by the thoughtfulness of her commander, Captain Blancart, and the second captain, M. Vogel. In fact, throughout a journey of nearly fifteen thousand miles we were shown unfailing hospitality and kindness by every official with whom we came in contact, from his Imperial Majesty the sultan of Morocco, who received me in audience in his palace at Marrákesh, to subalterns in command of lonely desert outposts.

That the long journey, much of it in desert regions, was so replete with material comforts, was due to the great kindness of M. Jean dal Piaz, president of the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique, and to his able assistants, M. Maurice Tillier, director-general of the company in Paris; M. Robert Hallot, Chef du Services des Auto-Circuits Nord-Africains, and M. Georges Paignon, manager of the North African Tours Department in New York, who generously placed at my disposal all the facilities of their vast organization. It will be noted that in the following pages I have repeatedly called attention to the services provided for the traveler in North Africa by the “Transat.” Not to mention the part played by this company in the opening up of Barbary would be equivalent to ignoring the work of Fred Harvey and the Santa Fé in the development of the American West.

I also welcome this opportunity of acknowledging my indebtedness to C. F. and L. S. Grant, authors of “African Shores of the Mediterranean”; to L. March Phillips, Esq., author of “In the Desert”; to Norman Douglas, Esq., author of “Fountains in the Sand”; to Frances E. Nesbitt, author of “Algeria and Tunisia”; to Charles Thomas-Stanford, Esq., author of “About Algeria”; to the late Budgett Meakin, Esq., author of “Life in Morocco”; and to Sir Harry H. Johnston, Frank E. Cana, Esq., and Edward Heawood, Esq., authors of monographs in the “Encyclopædia Britannica” on Tunisia, Algeria, and the Sahara respectively. From all of the above works I have obtained historic and economic data and many valuable suggestions.

E. A. P.

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | I Never See a Map but I’m Away | 3 |

| II. | The Gate to Barbary | 14 |

| III. | The Factory of Strange Odors | 26 |

| IV. | Mid Pleasures and Palaces | 42 |

| V. | Carthago Deleta Est | 56 |

| VI. | Ashes of Empire | 82 |

| VII. | To Kairouan the Holy | 100 |

| VIII. | Troglodytes and Lotus-Eaters | 119 |

| IX. | Across the Shats to the Sandy Sea | 144 |

| X. | The Conquest of the Sahara | 158 |

| XI. | The Last Home of Mystery | 179 |

| XII. | Down to the Land of the Mozabites | 203 |

| XIII. | Biskra, Demi-Mondaine of the Desert | 220 |

| XIV. | Frontiers of Rome | 238 |

| XV. | The Grand Kabylia | 263 |

| XVI. | The Capital of the Corsairs | 278 |

| XVII. | Following the Pirate Coast | 304 |

| XVIII. | The Foreign Legion | 323 |

| XIX. | The Struggle for Power in “The Farthest West” | 339 |

| XX. | From a Fasi Housetop | 374 |

| XXI. | In the Shadow of the Shereefian Umbrella | 400 |

| XXII. | South to the Forbidden Sus | 424 |

| A Short Glossary of Arabic Words and Phrases Commonly Used in Barbary | 459 | |

| Index | 469 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| FACING PAGE | |

| A soldier of Africa | Frontispiece |

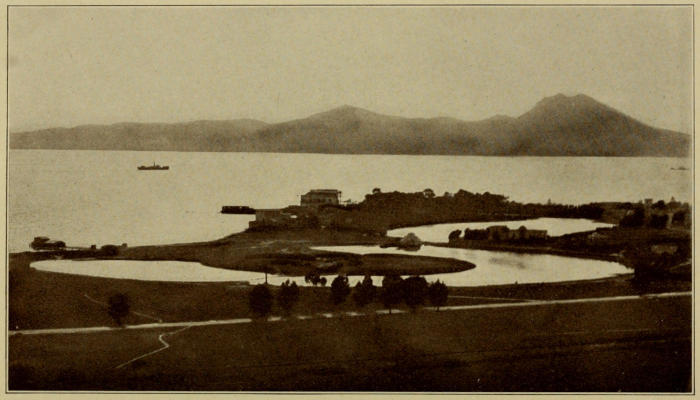

| Lo, all the pomp of yesterday | 17 |

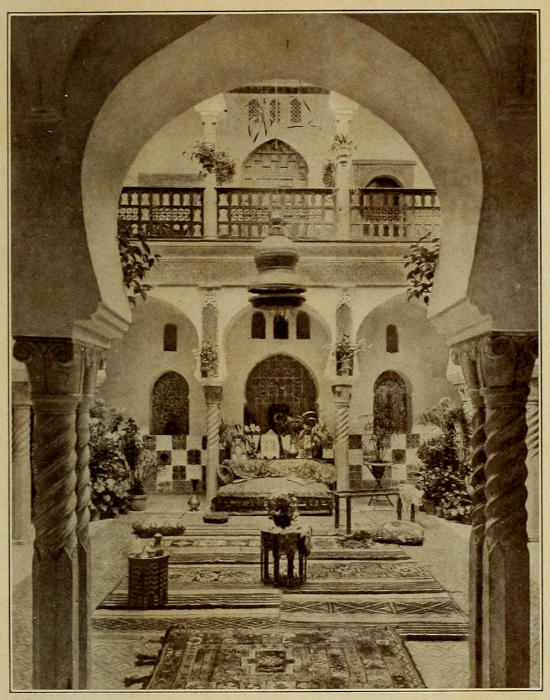

| Here Scheherazade might have told her tales | 32 |

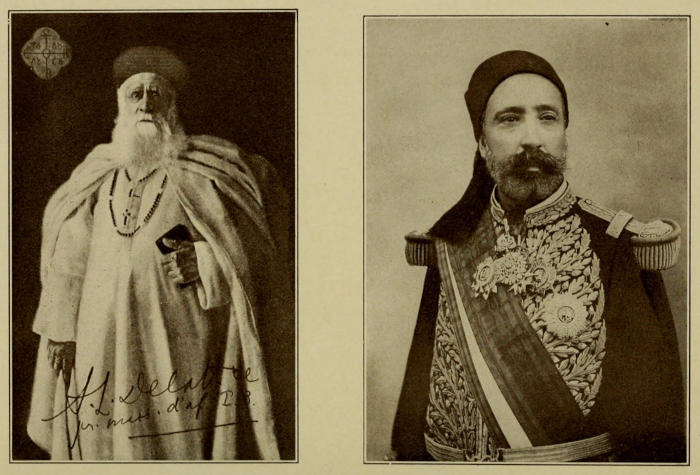

| Church and state in Tunisia | 37 |

| Thirteen centuries look down upon you | 44 |

| A gate to Barbary | 49 |

| They spend their holidays among the dead | 64 |

| The city of the mole-men | 85 |

| Homes of the Troglodytes | 92 |

| The voice from the minaret | 97 |

| The marabout in the desert | 112 |

| In the land of polygamy and passion | 117 |

| One of the most amazing ruins in the world | 121 |

| Medenine, the strangest city in the world | 124 |

| The Sun-God paints his picture in the West | 129 |

| Like feathered bonnets on the heads of a savage army | 144 |

| The fantastic dwellings of Mechounech | 149 |

| The forgotten of God | 156 |

| The sandy sea | 161 |

| Basking in the blinding sunlight of the Tunisian Sahara | 176 |

| The road to Timbuktu | 181 |

| Crossing the sand-dunes of the Grand Erg by motor | 185 |

| To prove that we were really there | 188 |

| A landmark for those who navigate the sea of sand | 193 |

| The shrine in the sands | 196 |

| The sand-storm | 205 |

| The sport of kings | 208 |

| The city of the Mozabites | 213 |

| Far hence, in some lone desert town | 217 |

| The start from Touggourt | 220 |

| The strange capital of a strange people | 225 |

| Desert damsels, old and young | 229 |

| What the pious Moslem expects to find in paradise | 236 |

| A Saharan market-place | 240 |

| The glory that was Rome | 245 |

| The city of the precipices | 252 |

| “Ul-l-l-l-l All-ah!” | 273 |

| Algiers, the capital of the Corsairs | 280 |

| Veiled women slip like sheeted ghosts | 288 |

| The resting-place of Cleopatra’s daughter | 304 |

| No, it is not always hot in Africa | 321 |

| The Moroccan is not afraid of mephitic maladies | 328 |

| The Riff | 357 |

| The price of empire | 364 |

| From out of the unknown | 369 |

| Strange folk from the far places | 372 |

| The panorama of the East | 381 |

| Forbidden to all save the faithful | 384 |

| In the city which gave the fez its name | 389 |

| Moroccan vaudeville | 392 |

| The Great Prayer outside of Fez | 396 |

| The harkas come down from the hills | 401 |

| A place of walled delight | 408 |

| The peace of Allah | 416 |

| The shadow of God on earth | 421 |

| A refuge of the rovers | 424 |

| The red city | 428 |

| The minarets of Marrákesh | 433 |

| The Aguenaou Gate of Marrákesh | 437 |

| The puppet and the man who pulled the strings | 440 |

| The empire-builder | 440 |

| Overlords of the southland | 444 |

| Most people think of Morocco as a semi-arid country | 448 |

| The stronghold of the Caïd Goundafi, overlord of the Forbidden Sus | 452 |

| A seat of feudal power | 456 |

| Maps | |

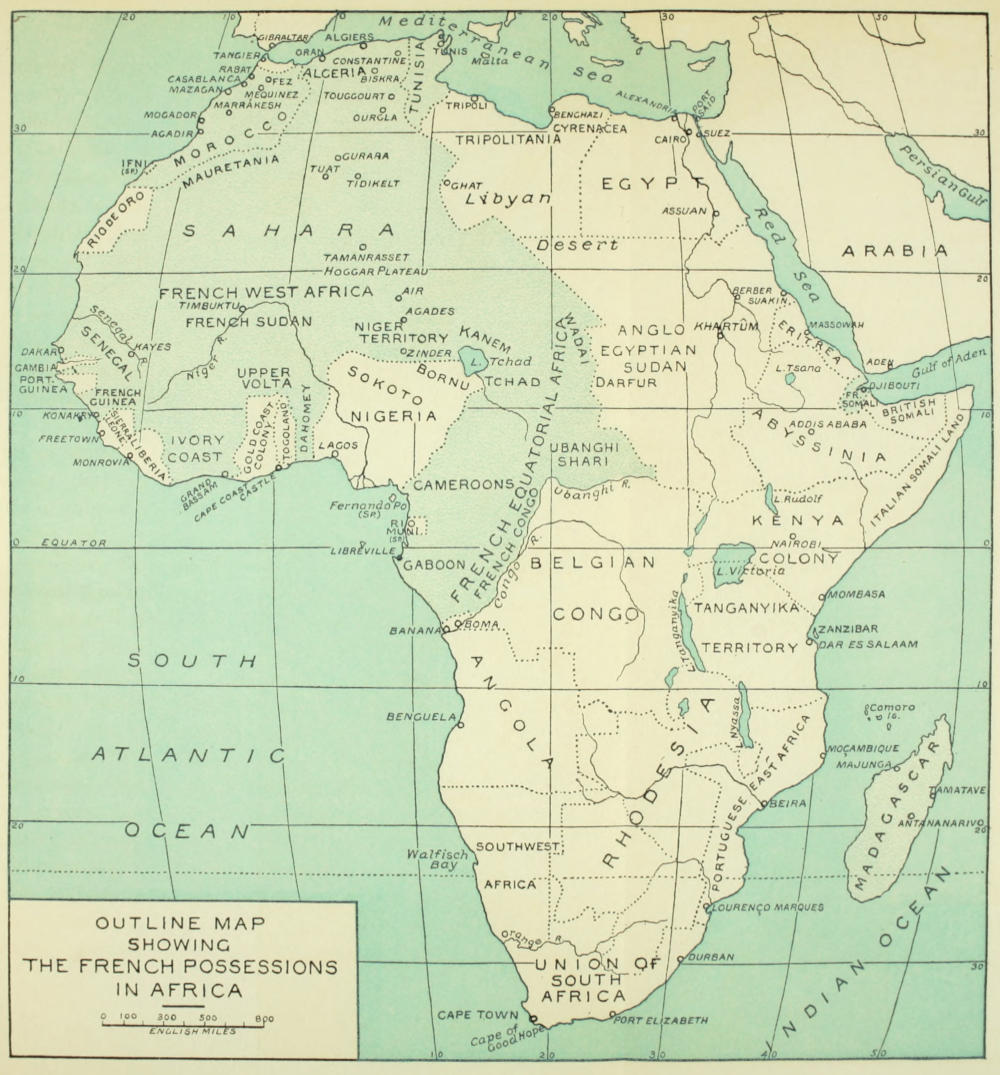

| Outline map showing the French possessions in Africa | 8 |

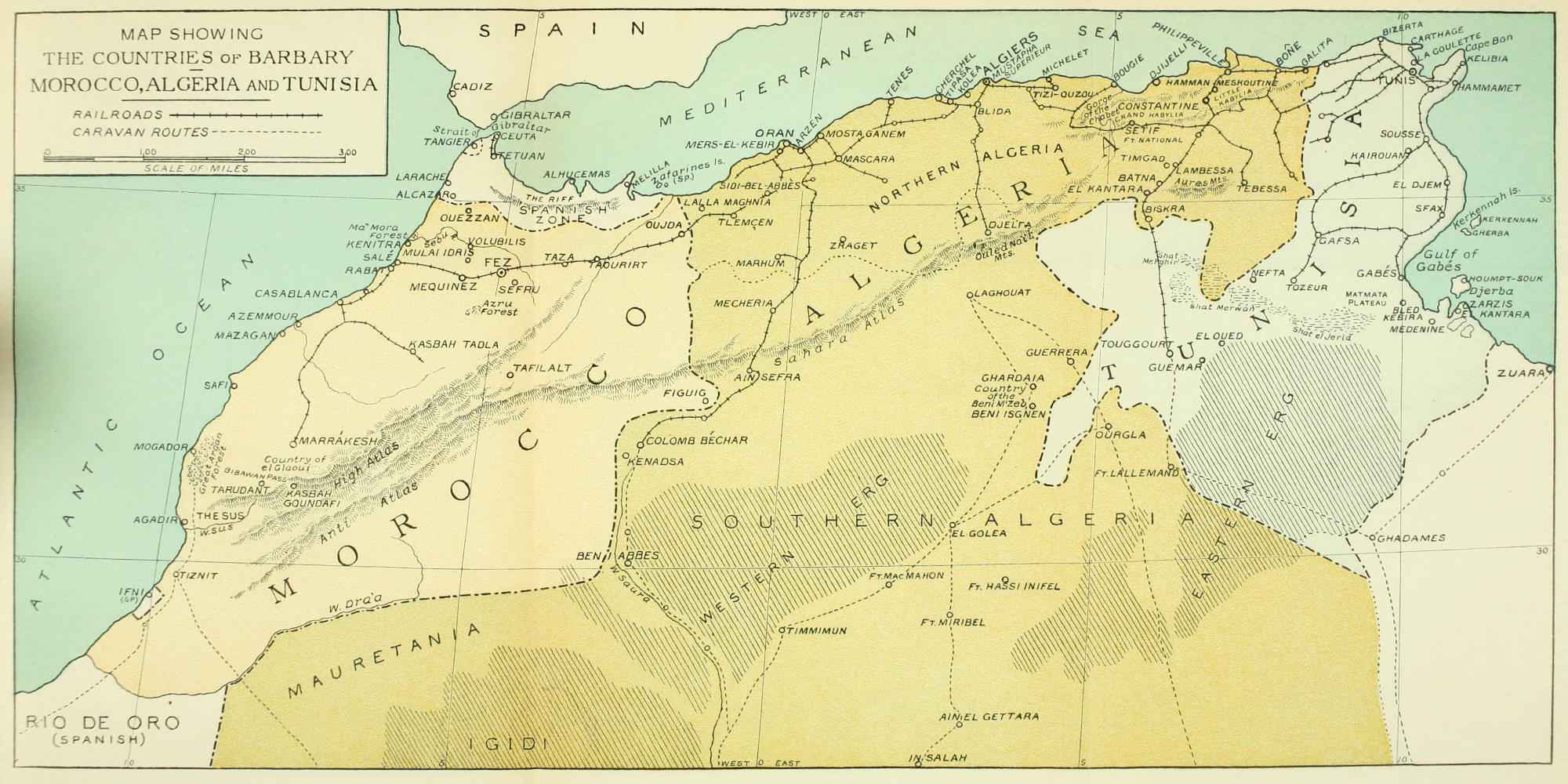

| Map showing the countries of Barbary | 24 |

IN BARBARY

CHAPTER I

I NEVER SEE A MAP BUT I’M AWAY

The wander-thirst is like the drug-habit. Once you acquire it you are done for. It will never let you rest. There is no mistaking its symptoms: a hatred of the prosaic, the routine, and the humdrum; an aversion to staying long in one place; an insatiable craving to move on, move on—to see what lies beyond yonder range of hills, around that next bend in the road.

It is as persistent as it is insidious. There comes the stage when you think that you are cured of it. You delude yourself into believing that you have had enough of discomforts and privations and that it is high time you settled down and had a home. You weigh the respective merits, as a place of residence, of Long Island and Southern California; you even consult an architect and subscribe to “House and Garden” and “Country Life.”

But one day you casually pick up a list of steamer sailings, or stumble on your battered luggage plastered over with foreign labels, or whiff some exotic smell which brings back memories of the hot lands (there is no sense which stimulates the memory like that of smell), or see a vessel outward bound, or idly open a map, whereupon the old craving suddenly grips you like an African fever, and, almost before you realize it, you are on the out-trail once again.

The symptoms usually recur with the approach of winter, when the northern days grow short and gloomy, when the shop-windows are filled with fur coats and mufflers and galoshes, when the wind howls mournfully beneath the eaves o’ nights. But the attacks which are hardest to resist come in the early spring, when the snow has disappeared, and the smell of fresh earth is in the air, and the country-side is already green in spots. That is the time when it is most difficult to control one’s restless feet.

For a quarter of a century the urge of spring had perennially sent me packing to the Far Places. But when I came up from Equatoria, after a year spent beneath the shadow of the Line, I said to myself that I was through with wandering as a vocation—that I was going back to my own country and my own people and on an elm-shaded street in some tranquil community buy me a long, low, rambling house—a white house with broad, hospitable porches and green blinds. I had carefully planned it all out on the long African marches or during sleepless nights beneath the Southern Cross. I would join the local golf-club, and amuse myself with my horses and my dogs and my books, and keep my house filled with friends over the week-ends, and even go into politics in a mild way, perhaps. In fact, I proposed to do all the sensible, prosaic things for which I had never had the time before.

But, before sailing for America to put these laudable resolutions into effect, I met at a Paris dinner-table the gentleman who was at that time charged with the conduct of France’s colonial affairs. We had much in common, it developed, for he too had been on those distant seaboards of the world where the Gallic empire-builders are creating a new and greater France. Lingering over the coffee and cigars we talked shop—the future of Indo-China, Madagascar’s need of harbors, Miquelon and its fisheries, the Syrian mandate, the control of sleeping-sickness in the Congo, cotton-growing in the country round Lake Tchad.

“Why don’t you round out your survey of our possessions,” the minister suggested, “by taking a look at what we’ve accomplished in North Africa?”

“The North African tour?” I asked, laughing. “Algiers, Constantine, and Tunis, with a side-trip to the Garden of Allah? Thank you, no. After what I’ve seen I’m afraid that I’d find that sort of thing pretty tame. Besides, I’ve already been to North Africa any number of times. I once spent a winter in Tunisia, and Algeria and I was in Morocco back in the bad old days when unsuccessful pretenders to the Shereefian throne were carried about the country in iron cages lashed to the backs of camels.”

“I’ll wager that I can name some places in North Africa that you haven’t seen,” the tempter said persuasively. “How about a visit to Djerba—the island of the lotus-eaters, you know—and the desert sky-scrapers of Medenine and the troglodyte dwellings of the Matmata Plateau? Then you could push down into the Sahara, cross the sand-dunes of the Grand Erg by twelve-wheeler to Ouargla and Ghardaia, keep on to the Figuig Oasis, and so over the Atlas into Morocco.”

“Yes,” I remarked speculatively, “if I were going to do it at all I should certainly include Morocco. There are some parts of it which I have never seen, and it has rather worried me. I’ve always had a hankering to have a look at some of those kasbahs in the High Atlas, where the grand caïds live like the marauding barons of the Middle Ages, I am told. And, while I was about it, I should like to get into the forbidden Sus, and even to see a bit of Mauretania and the masked Touareg, perhaps.”

“That can all be arranged quite easily,” the minister assured me. “If you decide to go, I’ll write to Marshal Lyautey, who runs the show for us in Morocco, and instruct the officers commanding in the Saharan military provinces to give you every assistance.”

“Suppose we have a look at the map,” I suggested, half capitulating. (I could feel the old familiar symptoms coming on; already my feet were growing restless.)

We appealed to our host, who led us into his library and on the table spread a large-scale map labeled “Afrique du Nord Française.” There they lay before me, tempting as jewels, those glowing lands of sun and sand, of Arab, Berber, and Moor, of mosque and minaret. Set in the Mediterranean shore-line like great fragments of colored mosaic were the Barbary States—Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco. Below them, sweeping southward to the Great Bend of the Niger and the swamps around Lake Tchad, was the yellow expanse of the Sahara, crisscrossed with the thin black lines which I knew for caravan-routes and sprinkled with the patches of green which stand for palm-shaded oases. And far to the westward, where Africa almost rubs shoulders with South America, lay Mauretania, land of the Blue-Veiled Silent Ones, The Forgotten of God.

Now I maintain that it is as unfair to unroll a map before a man who is striving to overcome the wander-thirst as it is to offer cocaine to a reformed drug-addict. For how, I ask you, could one be expected to resist the lure of those magic names—Kairouan, Gafsa, Touggourt, Ghardaia, Laghouat, Sidi-bel-Abbès, Oujda, Fez, Mequinez, Mazagan, Mogador, Agadir? At sight of them my resolutions crumbled like Mexican adobe. Almost before I realized it my carefully made plans had been tossed into the discard, and instead of poring over plans and specifications with an architect I was overhauling my travel-gear and ordering riding-breeches from my tailor and making inquiries about the sailing-dates from Marseilles.

Yes, it was the map that was my undoing, for

There are three routes from France to French North Africa, and they are all served by the steamers of the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique, or, as it is better known to Americans, the French Line. The first is from Bordeaux to Casablanca, the chief seaport of Morocco; a four-day voyage, this, half of it in the Bay of Biscay. Speaking for myself, I have never found that ill-reputed body of water anything save smooth, but doubtless that has been my good fortune. The second route is from Marseilles to Algiers by the Mediterranean greyhounds, swift, luxurious vessels which make the crossing in something under four-and-twenty hours, so that you have scarcely said good-by to Europe before you are being greeted by Africa. The third route, and the one which we took, is from Marseilles to Tunis—a two days’ voyage if the steamer is not detained at Bizerta.

Of course there are other roads to Africa; roads which are more picturesque and interesting, perhaps, provided that speed and comfort are not essential. Thus one may travel by the Sud Express from Paris to Algeciras, a charming little Spanish coast-town across the bay from Gibraltar, whence small and rather dirty vessels cross the straits thrice weekly to Tangier in Morocco. The chief objection to this way is that, in order to reach French Morocco and the main lines of travel, it is necessary to traverse the Spanish zone by motor-car, a somewhat arduous trip and one which has heretofore been subject to interruption because of the troubles in the Riff.

There is an even more out-of-the-ordinary route to Barbary, but it is uncertain and in parts exceedingly uncomfortable, so, unless the traveler is prepared to put up with delays and discomforts, I cannot recommend it. This is by the fortnightly Italian boat from Syracuse, in Sicily, to Tripoli and thence by narrow-gage railway along the coast of Tripolitania to the present end-of-steel at Zuara. Here, by making arrangements well in advance, it is usually possible to obtain a motor-car for the two-hundred-mile journey across the desert to the French rail-head at Gabés, in southern Tunisia.

In deciding to enter Barbary through the Tunisian gateway we were influenced by reasons historical, climatical, and sentimental. To the historically minded traveler the east-to-west journey is more satisfying than the reverse route because, going westward, he follows the march of history, the hoof-prints of the Islamic invaders who, sweeping out of Asia behind their horsetail standards, carried fire and sword and the green banner of the Prophet along the northern shores of Africa until, halted by the Atlantic, they swung northward into Spain. To travel in the opposite direction would be equivalent to reading history backward.

OUTLINE MAP SHOWING THE FRENCH POSSESSIONS IN AFRICA

Again, should you go to Barbary, as we did, in the late winter, the weather is more likely to be favorable in Tunisia than in Morocco, where cold, rain, and mud usually prevail until well into the spring. If, moreover, you purpose striking southward from Tunis into the desert, it is well to get that portion of the journey over with before spring is too far advanced, as after mid-April the heat becomes intolerable in the Sahara and the sirocco season begins.

From the dramatic point of view, as well, it is infinitely preferable to follow the journeying sun, for, whereas Tunisia is as civilized and well-behaved as Egypt, Morocco, save in spots, remains not far removed from barbarism, so that the peoples, customs, and scenes, instead of decreasing in novelty and interest as you press westward, become increasingly romantic and strange.

In making preparations for a journey in Barbary one should never lose sight of the fact that North Africa is a cold country with a hot sun. Most people, I find, labor under the delusion that Africa is synonymous with heat. This is due, I imagine, to our careless habit of generalization, of taking things for granted. Just as Canada was given a wholly undeserved reputation for frigidity by Kipling’s “Our Lady of the Snows,” so the pictures of sun-scorched deserts made so familiar by steamship-lines and tourist-companies have led to the assumption that every African country has, perforce, a torrid climate. Such misconceptions would be less general if people were more prone to consult the family atlas. There they would see that Tunis is on the same parallel as the city of Washington and that Algeria and Tunisia correspond in latitude to Virginia and North Carolina. The truth of the matter is that in the countries lying along Africa’s Mediterranean seaboard there are few evenings between November and May when a warm overcoat will be found uncomfortable, and even far south in the desert in the late spring I have shivered beneath three heavy blankets.

Yet an astonishingly large proportion of American visitors to North Africa appear to be wholly ignorant of the climatic conditions which prevail in that region. Staying in Biskra while we were there was a motion-picture company from California. While “on location” the actors wore pith helmets and white drill riding-breeches and shirts open at the neck and the other garments associated in the popular mind with life in the tropics, but, once the day’s filming was over, they wrapped themselves in sweaters, overcoats, and mufflers and huddled, shivering, about the open fire in their hotel. Those who saw that picture on the screen—it was called “Burning Sands” if I remember rightly—little dreamed that the actors who made it spoke their lines through chattering teeth and gesticulated with hands blue from cold.

There is one other popular misconception about North Africa which might as well be corrected now as later on. Save in the extreme south, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco are not flat, desert-like countries, as is frequently assumed. On the contrary, they are distinctly rugged and in parts extremely mountainous. Perhaps it will astonish some of my readers to be told that the High Atlas has a greater average height than the Alps and that at least one of the Moroccan peaks is higher than any mountain in the United States outside of Alaska. Though the Algerian ranges of the Atlas are not so lofty as those further to the westward, I have seen several inches of snow on the passes of the Grande Kabylie a few days before Easter.

I always like sailing from Marseilles. Perhaps it is because I have set out from there on so many long and fascinating journeys, but to me it has always been, along with Constantinople and Port Said and Singapore and Panama, a gateway to adventure.

On those sparkling blue-and-gold mornings for which the Côte d’Azur is famous I like to sit over my coffee beneath the striped awning of one of the restaurants along the Cannebière and watch the human panorama unroll itself before my eyes. Here one sees picturesque types from the Near, the Middle, and the Farther East; representatives of all of France’s far-flung colonial possessions. The gaunt, stooped man with the yellowed skin and tired eyes, in his buttonhole the red rosette of the Legion d’Honneur, is a colonial administrator, home on a much-needed and all too brief leave of absence from some God-forsaken outpost of empire in Syria, Somaliland, Madagascar, Indo-China. Here is a group of zouaves, boisterous, sun-bronzed fellows in tasseled fezzes and baggy scarlet trousers, fresh from service with the Army of Africa, who ogle every pretty girl they pass and pause for a round of drinks at every café. Tunisian marchands des tapis, gaudily colored rugs draped over their shoulders, shuffle along in heelless yellow slippers, urging their wares upon the patrons of the sidewalk restaurants until the exasperated waiters harshly order them away. A trio of bearded, grave-faced men, very dignified and aloof in their white hoods and flowing white burnouses, pace by unhurriedly, concealing their wonder at the unaccustomed scenes behind masks of Oriental imperturbability; they are powerful caïds from one of the Saharan provinces, visiting France for the first time as guests of the Republic. Down the center of the street, under the watchful eye of a grizzled sergeant, briskly marches a platoon of down-at-heel, out-at-elbow nondescripts—recruits for the Foreign Legion, with five years of iron discipline and heartbreaking desert service before them. Sauntering along beside a pretty woman is an officer of chasseurs d’Afrique, a light-opera figure in his flaring scarlet breeches, wasp-waisted sky-blue jacket, and képi piped with gold and silver braid. Staring with childlike curiosity at the displays in the shop-windows are yellow men from Annam, brown men from Tripolitania and the Red Sea countries, black men from the Ivory Coast and Senegal. Hulking negro stevedores rub shoulders with greasy, furtive-eyed seamen from Levantine coasters and Lascar stewards from the P. & O. boats in the harbor. Zigzagging along the pavement, arm in arm, comes a row of rollicking sailors from the fleet, scarlet pompoms on their rakishly tilted caps and the roll of the sea in their gait. And everywhere, seated at the café tables, mingling with the moving throng, are the filles de joie, the ladies of easy virtue, bold-eyed and carmine-cheeked, who find in the streets of the great seaport a happy hunting-ground.

When in Marseilles I like to make a little pilgrimage by funicular to Notre Dame de la Garde, the church of those who go down to the sea in ships, and, strolling through its dim, hushed transepts, to read the inscriptions, some naïve, some pathetic, on the hundreds of votive tablets placed there in gratitude and thanksgiving by those who have been saved from storm and shipwreck. I like to dine in the quaint little restaurants which fringe the waterfront on the delicacies for which Marseilles is famous—langouste, homard, crab, scallops, oysters, fish, and, of course, bouillebaisse. But particularly I like to stroll along the edge of the harbor, with its forest of masts and funnels, and watch the ships, flying the flags of many nations, coming from or setting forth for strange, far-off, outlandish ports on all the Seven Seas.

The short winter’s day was drawing to a close when the Duc d’Aumale nosed her way cautiously between the arms of the Marseilles breakwater and lifted to a choppy sea. From her lofty pinnacle above the city Our Lady on Guard seemed to bid us a benign farewell. Atop the cliffs off our port bow the Corniche Road twisted and wound and doubled upon itself like an uncoiled lariat tossed carelessly upon the ground. Further to the north, the peaks of the Maritime Alps reared themselves majestically skyward, purple-cloaked and ermine-caped. To starboard rose the rocky islet, crowned by the grim Château d’If, where Monte Cristo sought to ease his solitude by proclaiming, “The world is mine!” And before us, its foam-flecked surface turned to a field of dancing gold by the westering sun, stretched the Mediterranean—the road to Africa.

CHAPTER II

THE GATE TO BARBARY

Bizerta, the great naval base and fortress on the northern coast of Tunisia, is a French pistol aimed straight at the head of Italy—or perhaps it would be a closer simile to say the toe. It commands the narrowest part of the Mediterranean, where the Middle Sea contracts to a width of less than four score miles. In fact, were the French to mount on Cape Bon a gun having the range of the one with which, in the spring of 1917, the Germans shelled Paris, they could drop their projectiles on the shores of Sicily.

It will be remembered that when, in 1881, the bey of Tunis was forced to acquiesce in a French protectorate, the most violent resentment was aroused in Italy, which had long regarded Tunisia, with its large Italian population, as within her own sphere of influence and was only awaiting a propitious moment and a plausible pretext to bring that country under the rule of Rome. Even to-day, indeed, after more than a third of a century of French occupation, Mussolini and his fellow-imperialists regard Tunisia as a sort of African terra irredenta, which, when a favorable opportunity offers, they purpose to “redeem.” So, when the French began the construction of an impregnable stronghold at Bizerta in 1890, they made no secret of the fact that it was intended as a warning to Italy that the tricolor which had been raised over Tunisia nine years before would not be hauled down, and as a reminder to Britain that, Gibraltar, Malta, and the Canal notwithstanding, the Mediterranean was not a British lake.

During recent years the French government has poured out money like water in the development of Bizerta until to-day it is one of the strongest fortresses in the world. The Lake of Bizerta, which forms the inner harbor, accessible through the outer harbor and a canal, is nine miles from the sea and contains fifty square miles of anchorage for the largest vessels. A great arsenal has been created at Sidi Abdallah, at the southeastern extremity of the lake, with dry-docks for repairing the largest battle-ships, wharves, workshops, and warehouses, while at Ferryville, a few years ago a sandy waste, a modern town with well-built dwellings for the thousands of laborers employed in the dockyard has sprung up as though at the wave of a magician’s wand. Barracks have been built for the housing of the garrison, and the muzzles of long-range guns peer menacingly from the elaborate chain of fortifications which encircle the approaches to the harbor and the town. If, as has been hinted, Mussolini occasionally turns an acquisitive eye toward Tunisia, he should not overlook Bizerta. It would be a hard nut to crack.

My daughter, Bettie, had never been to Africa before, and so, when the steamer docked at Bizerta, she was naturally eager to go ashore and see the sights despite my warning that it was a colorless, uninteresting town, and that, as her first glimpse of Africa, it would be a disappointment. Now it is a curious fact that new-comers to a country frequently have more thrilling experiences in the first few hours of their visit than befall old-timers in a lifetime. For example, Sir Theodore Cook, editor of the “Field,” once told me that during his first day in New York, while drinking a glass of beer in a saloon in Park Row, the glass was shattered in his hand by a gangster’s bullet intended for the bartender.

It was a Sunday morning when we went ashore at Bizerta, and the town was as peaceful as a rural community in France. But as we were strolling through the tortuous byways of the picturesque Andalusian quarter—founded by the Moors driven from Spain—a pistol barked in a doorway, and the report was echoed by a woman’s scream. French gendarmes, native goumiers, and military police came on the run, followed, it seemed, by half the population of the town. In less time than it takes to tell about it the narrow thoroughfare was packed from wall to wall with an excited mob.

“What’s the trouble?” I inquired of a zouave who emerged from the press about the doorway.

“N’importe, m’sieur. N’importe,” he answered, shrugging his shoulders. “A rascally Senegalese has just murdered an Arab woman.”

“And you told me,” my daughter said reproachfully, “that I wouldn’t find Bizerta interesting!”

The dense gray fog, which had hung like a pall over the wintry Mediterranean since shortly after our departure from Marseilles, abruptly lifted as we left Bizerta, and thence onward to La Goulette the Tunisian coast unrolled its panorama bright and clear under the February sunshine. As I leaned on the rail, my glasses trained upon the shore-line, which slipped past as on a motion-picture screen, a White Father emerged from the smoke-room and joined me.

LO, ALL THE POMP OF YESTERDAY....

“Delenda est Carthago!” cried Marcus Cato, and so efficiently was his command carried out that two small lagoons—the one at the left corresponding to the ancient military harbour, the other to the commercial port—are almost all that remain of the great city founded by Dido

Shortly he tapped me upon the shoulder.

“Look, my son! Look! Over there....”

With my glasses I followed the direction of his outstretched finger. But all that I could discern was a range of distant violet mountains and in the middle foreground, rising somewhat abruptly from the plain which sloped down to meet the shingled strand, a low, isolated hill. Its lower slopes were clothed with vegetation—fields of barley, vineyards, patches of cactus—broken here and there by what appeared to be huge rubbish-heaps and excavation mounds. Higher up, amid dark clumps of cypress-trees, I could make out some scattered, white-walled buildings, one of them, judging from the gilded cross which surmounted it, a church. At the foot of the hill, near the margin of the sea, the sun was reflected dazzlingly from the surface of two small, curiously shaped ponds.

“Delenda est Carthago,” quoted the priest.

“There is all that remains,” he continued, “of what was once the most famous and powerful city in the world. The horseshoe-shaped lagoon with the island in its center is a vestige of Hamilcar’s military harbor, where the war-galleys were moored. On the summit of yonder hill Dido’s palace is believed to have stood. On that narrow neck of land to the eastward the army of Regulus was annihilated by the Carthaginians under Xanthippus, and there, a century later, the victorious forces of Scipio Africanus pitched their camp. The white chapel atop the plateau marks the spot where St. Louis died while leading the Last Crusade.”

It was as though he had uttered an incantation. At his words the scene seemed to change before my eyes as one stereopticon picture dissolves into another. The fog-banks which had lifted were the mists of centuries. Now I was looking down the vista of the ages. In my mind’s eye a mighty, glittering metropolis crowned that green and russet hill. A hot African sun beat down upon its massive ramparts, upon the gilded roofs of its towers and temples, upon its marble palaces and porphyry colonnades. Brazen chariots tore through its narrow, teeming streets; squadrons of horsemen maneuvered on the plain; elephants with jeweled trappings rocked and rolled along. The smoke of sacrificial fires rose from the altar before the great temple, where stood the statue of the horned god Baal. Relieving the masses of masonry here and there were patches of verdure, the sacred groves dedicated to the worship of the goddess Tanith. A vessel with billowing sails of Tyrian purple slipped along the shore. Out from the harbor-mouth shot a file of lean, long triremes, ostrich-feathers of foam curling from their bows as they leaped forward at the urge of the triple banks of oars. I was looking on the city which had been mistress of the Mediterranean for upward of half a thousand years; whose argosies had explored the unknown coasts of Africa and Gaul and Spain, venturing even beyond the Pillars of Hercules in their quest of the Hesperides; the city whose name is still synonymous with pomp and pride and power—Carthage, which had disputed the Empire of the World with Rome!

But the vision faded as abruptly as it had appeared when a French destroyer, inky clouds belching from her slanting funnels, fled across our bows. A sea-plane, bands of the tricolor painted on its under wings, went booming overhead. Fishing-craft with ruddy lateen sails appeared, swarthy, red-fezzed fishermen hauling at the nets. A puffing tugboat bustled officiously alongside, and the pilot nimbly climbed the swaying ladder. Bells jangled in the engine-room. And the Duc d’Aumale, slowed to half-speed, swept past the thickets of bristling masts which fringe the wharves of La Goulette and entered the throat of the buoyed channel which leads through the shallow lake of El Bahira to Tunis.

Though a seaport, Tunis, it should be understood, is not on the sea itself but some seven miles inland. The Tunisian capital occupies a most peculiar site, being built upon the narrow isthmus which separates the stagnant waters of El Bahira, “the little sea,” from the salt lagoon of Sebkhet es Sedjoumi. Notwithstanding the fact that, next to Algiers, Tunis is the largest and most important city in French Africa, it is only within recent years that it has been directly accessible to ocean-going vessels.

The project of creating a port at the very doors of Tunis was first entertained by the late bey, who in 1880 granted a concession for the purpose, but with the reorganization of the country after the French occupation the contract was canceled. Some years later, however, the enterprise was revived, the task of constructing the harbor, and of connecting it with the sea by dredging a canal, seven miles in length, through El Bahira, being undertaken by a French company.

With the completion of the port and the canal, La Goulette—or Goletta, as the English call it—lost its former importance, declining from a busy harbor, its roadsteads crowded with the ships of many nations, to a sleepy fishing-village. During the summer months, however, it regains a certain measure of its old-time activity, its population being almost doubled by the Tunisians who, unable to get away to Europe, go there for the sea-bathing and the breezes. Though La Goulette is of yesterday, its Venetian charm happily remains undimmed. Its houses, built with the stones of ancient Carthage, have been mellowed by time and the sun to ivory and terra-cotta; a reminder of its tumultuous past is provided by the fortress of Barbarossa, from which thousands of Christians taken captive by the red-bearded corsair were released when Charles V carried it by storm in 1535; the encircling waters of the Mediterranean and El Bahira are of a glorious blue, flotillas of fishing-barks with painted sails dot its placid surface and flocks of pink flamingos stalk sedately along its shores.

Darkness was close at hand when we steamed past La Goulette, and the purple African night had descended upon the land when we entered the harbor of Tunis. Dimly the old, old city loomed before us, its proportions clearly defined by twinkling street-lamps which grew fainter as they climbed the hill surmounted by the kasbah and the palace of the bey; while in the foreground danced the reflection of the riding-lights of the vessels in the harbor. I have always maintained that there are certain cities at which, in order to obtain the full flavor of their mystery and charm, one should arrive after nightfall, and Tunis is one of them.

While the steamer was being warped with aggravating deliberation into her berth, I looked down from the rail upon the picturesque scene and gave a sigh of contentment. It was good to sniff again the smell of Africa, to be back in the Orient once more. I breathed deep of the soft night air, laden with the fragrance of orange-blossoms, jasmine, and bougainvillea. After the glare of the sea, my eyes were rested by the dim outlines of the buildings, garish enough by day but of ivory and amber loveliness when bathed in the light of the moon. I reveled in the color and picturesqueness of the throng waiting on the wharf below.

Ranged along the edge of the quay, very gorgeous and self-important in their gold-laced jackets and voluminous trousers, were the dragomans and runners from the various hotels and tourist-agencies; alert, energetic fellows, speaking a smattering of many tongues, who spend their lives on steamship-wharves and railway-station platforms, welcoming the arriving and speeding the parting guest. Beyond them was a little group of wealthy young Tunisians, in immaculately ironed tarbooshes and spotless burnouses of the most delicate colors, one of them with a crimson blossom worn behind his ear, come to welcome some friend returning from Paris or Monte Carlo. A pair of bearded, hawk-nosed spahis paced slowly up and down, their enormous white turbans bound with ropes of camel’s-hair, long scarlet cloaks hanging to their booted and spurred heels. And well at the back, kept in their place by the whip of a native goumier, was a vociferous throng of Arab and negro porters, shouting and gesticulating for the first chance to make a franc by carrying ashore our luggage, and waiting, like sprinters on the mark, for the lowering of the gang-plank to storm the ship as their ancestors, the Barbary pirates, did of old.

Drawn up beside the customs shed was a powerful car of American make with a uniformed kavass from the residency and an alert-faced chauffeur in trim gray whipcord standing beside it.

“For Colonel Powell?” I asked the chauffeur in French as we set foot ashore.

“Yes, sir,” was the reply, in the unmistakable nasal twang of New England. “But you needn’t speak to me in French unless you want to. My name is Harvey Wilson and I’m from Providence, Rhode Island.”

Wilson, it developed, was a former member of the A. E. F. Instead of returning to America with his regiment after the Armistice, he had married a French girl and settled in Algiers as a motor mechanic and chauffeur. He drove us for upward of six thousand kilometers over desert roads, mountain roads, and across regions where there were no roads worthy of the name whatsoever. He had a profound knowledge of the idiosyncrasies of a motor; under the most trying conditions he never lost his patience or his temper; and his unfailing good humor won him the friendship of Europeans, Arabs, Berbers, and Moors alike. When we parted, months later, on the frontier of Morocco, I told him that it would give me genuine pleasure to recommend him to any one who contemplated motoring in North Africa, and I am now keeping that promise.

Mrs. Powell and I had been in Africa so many times that for us the drive through the brilliantly lighted streets to the hotel held little novelty. Our chief concern was whether we should find awaiting us a room with bath, for the hotels of Tunis are limited in number—the good hotels, I mean—and during the tourist season they are always overcrowded, so that it is the part of prudence to reserve one’s accommodations well in advance.

But my daughter Bettie was fascinated by the unfamiliar street scenes: the ceaseless stream of men wearing every form of head-covering—hats, helmets, hoods, tarbooshes, turbans; the stately Arabs, the elders looking for all the world like Old-Testament patriarchs; the bare-legged Berber porters in ragged garments of coarse brown camel’s-hair, sacks drawn over their heads to be used as sun-shades or overcoats according to the weather; the gaudily uniformed soldiers of the Beylical Guard, who might have stepped straight from a comic-opera chorus; the veiled women slipping silently along like sheeted ghosts; the groups of natives squatted about their cooking-pots, from which strange smells assailed the nostrils; the files of swaying, supercilious camels laden with the products of the South; the droves of patient little asses trotting demurely along beneath enormous burdens; the high whitewashed walls of the houses, broken by mysterious latticed windows, from which the eyes of unseen, jealously guarded women were peering down, no doubt; the fleeting glimpses caught through doors ajar of Oriental courtyards filled with color—to her this was one of the Thousand and One Nights. Ah, me ... what wouldn’t I give to again be seeing Africa for the first time through the eyes of youth!

Notwithstanding the French occupation, Tunis remains distinctly Oriental. The town is like a veiled woman of the harem wearing a pair of European shoes, incongruous and clumsy. And it is the shoes which the visitor arriving by sea sees first. For the district bordering on the harbor is Italian—an unlovely, odoriferous neighborhood of mean streets lined with squalid hovels where dwell some fifty thousand Sicilians and Maltese, who outnumber the French by more than two to one—while the quarter bisected by the Avenue Jules Ferry is characteristically French, with spacious, tree-planted boulevards, enticing shops, banks, theaters, cinemas, and electric tram-cars. This really imposing thoroughfare, with its fine stores and crowded open-air cafés, might be, indeed, a sort of continuation of the Cannebière in Marseilles interrupted by the Mediterranean. Its principal mercantile establishment, the Petit Louvre, is a creditable imitation of the mammoth Magazins du Louvre in Paris, with which, incidentally, most American women appear to be better acquainted than they are with the palace of the same name on the other side of the Rue de Rivoli. But all this, I repeat, is only that portion of Tunis revealed below the hem of her enveloping Eastern garments. The old Tunis, with its mosques and palaces, its labyrinth of bazaars rising gradually to the kasbah, is as Oriental as the Baghdad of Harun-al-Rashid.

Most Europeans seem to be under the impression that Tunis is a modern city—modern, at least, in comparison with Carthage. As a matter of fact, however, Tunis (or Thines, as it was originally known) had probably been in existence for some three or four hundred years when the fugitive Dido landed on the shores of the Gulf of Tunis and on the little hill of Byrsa founded Carthage. This view is accepted by no less an authority than the historian Freeman. But for centuries Tunis was overshadowed and eclipsed by the magnificence of her younger sister, sinking to the position of a poor relation, a country cousin, a mere dependency. Yet she had her revenge. Not only has she outlived her haughty neighbor, but she has incorporated her very bones, for there is hardly a column or capital in Tunis which is not of Carthaginian origin. Here, indeed, we see a ghost of Carthage, for the native city must very closely resemble what the commercial quarter of Carthage was five-and-twenty centuries ago.

MAP SHOWING THE COUNTRIES OF BARBARY

MOROCCO, ALGERIA AND TUNISIA

The car came gently to a halt before the Hotel Majestic, a spacious hostelry whose architect had sought, without conspicuous success, to graft the Moorish style on the European. An Arab chasseur in red and gold flung open the door. A swarm of servants in green baize aprons hurled themselves upon our luggage. We were greeted by the director, a suave Frenchman, who might have been an undertaker, judging from his somber garments and excessive dignity. Rooms had been reserved for us by the residency, he said. I remarked that I hoped that we were to have a bath. Mais certainement, un grand bain—un bain de luxe. Would we ascend and view it? We crowded, the four of us, into an ascenseur which could not possibly have been intended to carry more than two, and the Arab lift-boy squeezed himself in after us. It creaked, groaned, hesitated, almost stopped, but finally drew level with the floor which was its destination. I gave a sigh of relief, as I always do upon completing an ascent in a French elevator. We were ushered down an echoing, marble-paved corridor, chilly as a tomb, to our rooms. Mrs. Powell tried the hot-water faucet and inquired about the voltage for her electric curling-iron. I sent the maid scurrying for extra blankets and softer pillows, and ordered a drink of Scotch. But my daughter Bettie stood on the balcony in the moonlight, looking out upon the white city and inhaling the subtle fragrance of the orange-blossoms. You see, she had never been in Africa before.

CHAPTER III

THE FACTORY OF STRANGE ODORS

The extraordinary success which has marked the rule of the French in North Africa is in large measure attributable to their policy of scrupulously refraining from encroachment on native life. Instead of being ruthlessly mutilated to make way for boulevards and plazas, as Baghdad and Delhi have been by the British, the old cities have been left intact; and the French quarters, with their public buildings, theaters, shops, and restaurants, have grown up outside the walls; so that the Europeans and the natives really dwell apart, which is best for them both.

The happy results of this policy are particularly noticeable in Tunis, where the French have made no attempt to modernize the ancient city, the Medina, access to which is gained from the European quarter through the old water-gate, Bab-el-Bahar, now known as the Porte de France. Though electric tramways encircle the city and run far into the suburbs—the service between Tunis and Carthage, I might remark in passing, is surpassed only by that between Yokohama and Tokio—all proposals to disfigure the picturesque native quarter have met with a stern refusal from the authorities. Street-names, lighting, and sanitation have been introduced, however, and the old town itself is incredibly clean for an Eastern city; cleaner by far than many cities in Italy and Spain. In fact, Tunis merits the title of “The White,” which it has so long enjoyed, almost as much by virtue of its astonishing cleanliness as because of its snowy buildings, which mount, tier above tier, to the citadel, like “a burnous with the Kasbah for a hood.”

In these Moslem lands, where religious fanaticism goes hand in hand with suspicion of the foreigner, the French have had to exercise the utmost tact in effecting even the most urgent sanitary reforms. M. Jusserand, for years French ambassador to the United States, once told me that, when he was chief of the Tunisian Bureau of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the city of Tunis was threatened by an epidemic because the bodies in the local cemeteries were too near the surface. Instead of arbitrarily ordering the graves to be deepened, an action which inevitably would have aroused native resentment and perhaps have precipitated serious troubles, the French resident-general sent a politely worded message to the chief cadi, the head of the Moslem religious community, inquiring whether the depth of graves was specified in the Koran. He was informed that, according to Koranic law, graves must be deep enough to cover a standing man to his shoulders. Thus scripturally fortified, the resident-general called the attention of the chief cadi to the failure of the Tunisians to abide by the tenets of their own religion, whereupon the natives lost no time in deepening the graves themselves.

The principal approach to the old city is through the Avenue Jules Ferry, a wide and handsome boulevard lined on either side with shops, banks, cafés, and theaters and having a sort of park running down the center. With its broad pavements, its fine trees, its beds of brilliant flowers, and its throngs of promenaders, it is strongly reminiscent of the Rambla in Barcelona. It terminates in the Place de la Résidence, a spacious plaza flanked on one side by the cathedral, a conspicuous building of dubious architectural merit which is the seat of the primate of all Africa, and on the other by the palace of the French resident-general, so that the representatives of church and state directly face each other. The residency is a low, unpretentious building with fine gardens, before whose gilded gates pace sentries in the brilliant uniform of the Garde Beylicale. Forming a continuation of the Avenue Jules Ferry is the shorter and narrower Avenue de France, which terminates at the Bab-el-Bahar, the entrance to the Medina, or old town. Though the Medina was formerly encircled by walls, these have in large part disappeared, leaving the gates of the city isolated, like those of Paris.

To pass through the Bab-el-Bahar is to enter another world, to go back into history for a thousand years, to step from the Europe of to-day straight into the Orient of the Middle Ages. I can recall few, if any, places where so abrupt a change takes place within a few paces, where the contrast is so startling. The gate, in itself quite unimposing, opens upon a kaleidoscope of color, a chaos of confusion, a pandemonium of noise. Here wheeled traffic virtually ceases, not because it is forbidden but because it is impracticable by reason of the extremely narrow and densely crowded streets. Here the raucous honk of motor-cars is replaced by the imperative “Barek balek!” (take care!) of Arab muleteers. Here, instead of carts and camions, the draft work is performed by files of mangy, moth-eaten camels, as far removed from the graceful méhari of the desert folk as a work-horse is from a thoroughbred; by droves of diminutive donkeys, blue beads festooned around their necks for superstitious reasons, their ears and tails alone visible beneath their enormous burdens; and by brawny porters, twin brothers to the hamals of Turkish cities, who stagger along beneath bales and boxes which would cause an American express-man to go on strike were he asked to handle them, but which they seem to carry with comparatively little effort by means of a rope passed round the forehead, like the tump-line of an Indian guide. I saw one of these fellows, a bare-armed, bare-legged Hercules, walk off quite matter-of-factly with a grand piano on his back.

Guides, touts, and Jewish shopkeepers do their utmost to ruin the visitor’s enjoyment by their incessant importunities and whines. “Good morning, meester.... Good morning, madame.... How are you?... Look here.... I show you sometheeng ... sometheeng ver’ fine ... ver’ cheap ... no charge ... you come in quite free ... you not buy anything unless you wish.... No, sare, I not damn nuisance.... I ver’ honest fellow....” Cringing, impudent, and furtive-eyed, they are as pertinacious as flies and as irritating as fleas, the only wonder being that they are not occasionally murdered by Europeans who have been exasperated beyond endurance. On one occasion I saw a Frenchman kick one of these parasites the entire length of a souk, and I felt like shaking hands with him as a public benefactor.

Now and then a gorgeously appareled caïd, a figure out of the Arabian Nights, clatters through the narrow streets astride a snorting Arab, negro slaves trotting at his stirrups. Snake-charmers, fire-eaters, story-tellers, do their hackneyed stuff in the open spaces before the city gates, surrounded by spectators packed four-deep who applaud the performances with the naïveté of children. The faithful squat beside the fountains of the mosques, bathing their hands and feet and rinsing their mouths in running water, as the Koran prescribes, before entering the sanctuaries to prostrate themselves in prayer with their faces toward the Holy Places. Occasionally one sees a wild-looking scarecrow of a figure, a holy man from the desert, caked with filth, his hair and beard matted, his patchwork rags of many colors, beseeching the passers-by in a shrill whine for alms in the name of Allah the Compassionate, the Merciful—and cursing them with enviable fluency if his importunities go unheeded.

The most characteristic and interesting feature of Tunis is the souks, or covered bazaars. Nowhere in the Nearer East are there any souks which can equal them; for in Constantinople, by virtue of the Angora government’s passion for westernizing everything Turkish, the men have been compelled to discard their turbans and tarbooshes for hats and caps and the women to doff their mystery-suggestive veils, more’s the pity! The bazaars of Cairo are not only deficient in architectural merit but, particularly during the tourist season, are not much better than the Oriental section of an exposition. In Damascus the bazaar buildings resembled railway-stations even before French shells laid in ruins the Street Which Is Called Straight. Indeed, one would need to go as far eastward as Tehran or Ispahan to find souks which can compare with those of Tunis in extent, beauty, color, and picturesqueness.

The bazaar quarter of Tunis is, as it were, a whole city under one roof—a city teeming with Oriental life; carrying on its trade in the traditional Eastern fashion; transacting its business without tables or chairs in doorless, windowless stalls, raised three or four feet above the ground and most of them only a few yards square, which their owners close at night by means of stoutly built, gaily painted shutters. In these recesses the merchants sit cross-legged, like so many Buddhas, with their merchandise spread about them, dozing, smoking, sipping black coffee, and gossiping with their neighbors.

The souks of Tunis cover an enormous area. They consist of a labyrinth of narrow, tortuous, wholly irregular streets, lanes, alleys, and passages; some of them vaulted, lighted only by shafts of sunlight falling through square apertures overhead; others roofed with sloping planks, uneven and rotting with age but highly picturesque, their gaping crevices permitting the street below to be flooded with sunshine or with rain. But most fascinating of all, at least in clement weather, are those bazaar lanes which are shielded from the elements only by vine-covered trellises, like pergolas, the sunlight, sifted and softened by the leaves, casting shadows of lace-like delicacy upon the worn, uneven pavement.

Each of the trades has its own souk, and each souk has its own distinctive character. Thus one street is devoted to perfumes, another to shoes, a third to jewelry, a fourth to saddlery, and so on; an arrangement which tends to make shopping easy, as the visitor in quest of a particular article is enabled to compare prices and quality and, not infrequently, to play off one merchant against another. Some of the souks contain only goods for sale, but most of them are workshops as well, the goods being made by native artisans on the premises. Here, if you require an article of special design, the merchant does not tell you that he will “order it from the factory,” but instead he cuts it, or carves it, or paints it on the spot and under your supervision. They are as enchanting as they are bewildering, these Tunisian souks—a source of unending novelty, a panorama of pure color, the dusky light which prevails beneath the vaulted roofs serving to harmonize the tints, to soften the harsher outlines, to fill the dark recesses with mystery.

And everywhere is the loot of Carthage. Those fluted marble columns, now striped in green and scarlet, like sticks of peppermint candy, may once have supported the roof of Dido’s palace. Those exquisitely sculptured capitals, their delicate tracery all but concealed beneath repeated coatings of whitewash, were in all likelihood executed by Phenician workmen, dead these twenty centuries and more, for the temple of the goddess Tanith. Yonder slab of polished stone, on which the shoemaker is seated, quite possibly stood in ancient times before the statue of the great god Baal, dripping with the blood of human sacrifices. Who knows?

On a first visit to the souks it seems impossible to think of finding one’s way unguided through this bewildering network of narrow, winding thoroughfares, this human rabbit-warren. Here, as in the even more extensive and confusing bazaars of Tehran, I felt like taking a ball of string along and unwinding it behind me, like an explorer of a subterranean cavern, so that I might find my way back to my starting-point again. But after a time the general topography becomes clear, and then it is easy to wander in and out at will, with the assurance that confusion, or even a total loss of bearings, means nothing worse than an extra turn or two and then the sight of some unmistakable landmark, such as the green sarcophagus which all but blocks the narrow way through the street of the leather-workers. It is the coffin of a marabout—an itinerant holy man—set there to confer a special blessing on the souks by its presence. It is painted a vivid green, ornamented with designs in red and yellow, and the garments of the endless stream of humanity which pushes past it have put a high polish on its edges. Personally, were I a merchant, I should not care to have a coffin resting permanently at the front door of my business premises, but the Tunisians seem to regard it very much as Grant’s Tomb is regarded by the dwellers on Riverside Drive.

HERE SCHEHERAZADE MIGHT HAVE TOLD HER TALES

Seated cross-legged on the cushion-piled divan, with silken carpets at her feet, soft music of flute and viol floating down from the balcony, the air heavy with the fragrance of flowers and incense, black slaves to wait upon her, and guardian eunuchs at the gate

Sooner or later every visitor to Tunis finds his way, or is led by his guide, to the Souk-el-Attarin, the street of the perfume-sellers. Architecturally, this is one of the finest bazaars in the city and probably one of the oldest. From its hole-in-the-wall shops drift the scents of all the world—attar of roses and ambergris, musk and incense, violet and orange-flower, jasmine and lily-of-the-valley. Before the shops stand sacks stuffed with the dried leaves of aromatic plants from which is made the incense used in the mosques and the henna with which the native beauties redden their hair and their finger-tips and the soles of their feet, for even the veiled women of the East are addicted to the use of war-paint.

The scents are very powerful, and for toilet purposes must be largely diluted with alcohol. Nor are they by any means inexpensive, even according to American standards, a tiny vial of certain of the rarer essences frequently costing several hundred francs. They are sold in slender, fragile bottles, charmingly decorated with gold and color, but, unfortunately, their glass stoppers rarely fit, and, as my wife and daughter learned by costly experience, the scent will evaporate unless the stopper is replaced with a cork. Here one’s nostrils are assailed not only by the old familiar perfumes but by the strange scents characteristic of the East—musk, amber, incense, attar of roses, and, of course, the celebrated parfum du bey. The last-named is the royal scent, a composite essence, the odor of which is alleged to change from hour to hour and which is unobtainable, at least in theory, save by those connected with the court or who are honored by the bey.

The perfume-sellers are the aristocrats of the souks, claiming to be descended from the Moors who were expelled from Spain and to possess the keys of the Andalusian castles owned by their ancestors. Be this as it may, they are very haughty and condescending, deeming it vastly beneath their dignity to haggle with their customers or to solicit the patronage of the passers-by. In fact, these small, luxuriously furnished shops, with their silken cushions, their seven-branched candlesticks, their array of slim, glass-stoppered bottles inscribed in gilt with mysterious Arab characters, and the hint of incense in the air, resemble shrines of Venus rather than places of business, the sleek, urbane proprietors exhibiting their wares with the reverence of officiating priests.

Here the purchase of scent is not a commercial transaction but a ceremony. The customer is seated upon a divan, piled high with cushions, and the turbaned merchant takes his place behind a table, on which are laid out fantastically shaped vials and vessels, like a sorcerer about to begin his mystic rites. The perfumes sold here, remember, are not the ordinary scents of commerce with which we Westerns are familiar, but concentrated quintessences, the merest drop of which upon a handkerchief or glove or sleeve confers a fragrance which will last for days. A silent-footed attendant serves tiny cups of coffee, thick, sweet, and black as molasses, and scented cigarettes. A charcoal brazier is smoldering in the corner, and from it rises a faint suspicion of incense. Daintily opening with delicate, tapering fingers the glass-stoppered bottles ranged before him, the perfume wizard runs through the whole gamut of odors; he plays upon the sensitive olfactory nerves as a great musician plays upon an organ. For, of all the senses, that of smell is most closely associated with remembrance. It can recreate a vanished vision on the human motion-picture screen we call the mind. It can arouse the emotions—pain, pleasure, passion, longing, sadness—and fan into flame the embers of the past. It can bring back, as at the wave of a magician’s wand, the thoughts and scenes of far away and long ago.

Perhaps I myself am more susceptible than most to the effect of perfumes ... I do not know. But the scent of roses brings back with overwhelming vividness the loveliness of a Capri rose-garden where I wandered with Her in the fragrance and the moonlight, long, oh, long ago. The redolence of cedar, and I see in my mind’s eye a carpenter’s shop which I passed daily when I lived in Syria, with the white-turbaned, patriarchal carpenter working at his bench amid a litter of shavings, and camels, laden with logs from the Cedars of Lebanon, kneeling patiently at the door. Sandalwood conjures up a vision of Indian temples, with shafts of sunlight striking through the murky interiors to be reflected by brazen buddhas, inscrutable of face; of twilight on the Ganges at Benares; of the pink palaces and towers of Jaipur. Geranium, heliotrope, lemon verbena—these show me once again the stately, white-pillared house in which I was born, with my grandmother bending lovingly over the flowers in her old-fashioned garden, the stretches of close-cropped greensward, the leaves of the old, old elms whispering ever so gently in the summer breeze.

Because I am a collector of weapons and curios in a modest way, and because I positively revel in colors, I lose no time when in Tunis in making my way to the Souk des Etoffes. To my way of thinking it is one of the most fascinating streets in the world, its tiny shops literally filled to overflowing with silks, damasks, velvets, brocades, embroideries, of every tone and texture—turquoise blue, pale green, amethyst, ruby red, old rose, burnt orange, purple, magenta, vermilion, saffron yellow—the fruit of looms all the way from India to Morocco. Stacked high are piles of carpets from Anatolia, Kurdistan, Daghestan, Persia, Afghanistan, Kairouan; the last-named a Tunisian product, surprisingly cheap but well worth buying, for it is as thick and soft as a fur rug, in lovely, mellow shades of ivory, red, and brown.

These Tunisian rug-merchants are past masters in the fine art of salesmanship; they will fling a silken carpet into the air with the hand of a magician and permit it to settle gradually upon the floor, not flat but in little hills and valleys of rich, tempting colors, the folds serving to reveal the intricacy of the design and accentuating the silky sheen.

I have no slightest intention of purchasing a carpet, no place to use one if I had it, but, for the sake of politeness, I feel constrained to ask its price.

“Twelve hundred pounds,” says the merchant, without batting an eyelash.

“Trop cher,” I remark, as though buying six-thousand-dollar carpets was with me an everyday affair.

CHURCH AND STATE IN TUNISIA

Father Delattre, in charge of the excavations at Carthage

H. H. Sidi Mohamed el Habib, Bey of Tunis

The merchant shrugs his shoulders as though pitying my ignorance of values. It is a very fine carpet, he assures me earnestly, very old, very rare. The “ivory” in it is quite exceptional. Only last week he sold a pair of such carpets to the American millionaire, Meester Otto Kahn. By way of convincing me he displays the New York banker’s visiting-card.

“But I am not a millionaire,” I explain.

“Monsieur is pleased to jest with me,” says the merchant flatteringly. “Is he not an American?”