My Memoirs, Vol. I, 1802 to 1821

Alexandre Dumas

MY MEMOIRS

BY

ALEXANDRE DUMAS

TRANSLATED BY

E. M. WALLER

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

ANDREW LANG

VOL. I

1802 TO 1821

WITH A FRONTISPIECE

NEW YORK

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1907

NOTE

The translator has, in the main, followed the edition published at Brussels in 1852-56, in the Preface to which the publishers state that they have printed from "le manuscrit autographe" of the author. They furthermore print a letter from Dumas, dated Brussels, 23rd December 1851, in which Dumas says:

"Je vous offre donc, mon cher Meline, de revoir moi-même les épreuves de votre réimpression, et de faire de votre édition de Bruxelles la seule édition complète qui paraîtra à l'étranger."

The translation has been collated (a) with the current edition, and (b) with the original edition published in Paris in 1852-55, and certain omitted passages have been restored. Dumas' spelling of proper names has been followed save in a few cases deemed to be misprints.

THESE MEMOIRS ARE DEDICATED TO

THE HONOURABLE

COUNT ALFRED D'ORSAY

MY FELLOW-CRAFTSMAN

AND MY BOSOM FRIEND

ALEXANDRE DUMAS

CONTENTS

BOOK I

CHAPTER I

My birth—My name is disputed—Extracts from the official registers of Villers-Cotterets—Corbeil Club—My father's marriage certificate—My mother—My maternal grandfather—Louis-Philippe d'Orléans, father of Philippe-Égalité—Madame de Montesson—M. de Noailles and the Academy—A morganatic marriage 1

CHAPTER II

My father—His birth—The arms of the family—The serpents of Jamaica—The alligators of St. Domingo—My grandfather—A young man's adventure—A first duel—M. le duc de Richelieu acts as second for my father—My father enlists as a private soldier—He changes his name—Death of my grandfather—His death certificate 11

CHAPTER III

My father rejoins his regiment—His portrait—His strength—His skill—The Nile serpent—The regiment of the King and the regiment of the Queen—Early days of the Revolution—Declaration of Pilnitz—The camp at Maulde—The thirteen Tyrolean chasseurs—My father's name is mentioned in the order of the day—France under Providence—Voluntary enlistments—St.-Georges and Boyer—My father lieutenant-colonel—The camp of the Madeleine—The pistols of Lepage—My father General of Brigade in the Army of the North 21

CHAPTER IV

My father is sent to join Kléber—He is nominated General-in-Chief in the Western Pyrenees—Bouchotte's letters—Instructions of the Convention—The Representatives of the People who sat at Bayonne—Their proclamation—In spite of this proclamation my father remains at Bayonne—Monsieur de l'Humanité 33

CHAPTER V

My father is appointed General-in-Chief of the Army of the West—His report on the state of La Vendée—My father is sent to the Army of the Alps as General-in-Chief—State of the army—Capture of Mont Valaisan and of the Little Saint-Bernard—Capture of Mont Cenis—My father is recalled to render an account of his conduct—What he had done—He is acquitted 43

CHAPTER VI

The result of a sword-stroke across the head—St. Georges and the remounts—The quarrel he sought with my father—My father is transferred to the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse—He hands in his resignation and returns to Villers-Cotterets—A retrospect over what had happened at home and abroad during the four years that had just elapsed 56

CHAPTER VII

My father at Villers-Cotterets—He is called to Paris to carry out the 13th Vendémiaire—Bonaparte takes his place—He arrives the next day—Buonaparte's attestation—My father is sent into the district of Bouillon—He goes to the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse and to the Army of the Rhine, and is appointed Commandant at Landau—He returns as Divisional General in the Army of the Alps, of which he had been Commander-in-Chief—English blood and honour—Bonaparte's plan—Bonaparte appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Army of Italy—The campaign of 1796 69

CHAPTER VIII

My father in the Army of Italy—He is received at Milan by Bonaparte and Joséphine—Bonaparte's troubles in Italy—Scurvy—The campaign is resumed—Discouragement—Battle of Arcole 82

CHAPTER IX

The despatch is sent to Bonaparte—Dermoncourt's reception—Berthier's open response—Military movements in consequence of the despatch—Correspondence between my father and Serrurier and Dallemagne—Battle of St.-Georges and La Favorite—Capture of Mantua—My father as a looker-on 90

CHAPTER X

My father's first breeze with Bonaparte—My father is sent to Masséna's army corps—He shares Joubert's command in the Tyrol—Joubert—The campaign in the Tyrol 109

BOOK II

CHAPTER I

The bridge of Clausen—Dermoncourt's reports—Prisoners on parole—Lepage's pistols—Three generals-in-chief at the same table 119

CHAPTER II

Joubert's loyalty towards my father—"Send me Dumas"—The Horatius Codes of the Tyrol—My father is appointed Governor of the Trévisan—The agent of the Directory—My father fêted at his departure—The treaty of Campo-Formio—The return to Paris—The flag of the Army of Italy—The charnel-house of Morat—Charles the Bold—Bonaparte is elected a member of the Institute—First thoughts of the expedition to Egypt—Toulon—Bonaparte and Joséphine—What was going to happen in Egypt 135

CHAPTER III

The voyage—The landing—The taking of Alexandria—The Chant du Départ and the Arabian concert—The respited prisoners—The march on Cairo—Rum and biscuit—My father's melons—The Scientific Institute—Battle of the Pyramids—Scene of the victory—My father's letter establishing the truth 151

CHAPTER IV

Admissions of General Dupuis and Adjutant-General Boyer—The malcontents—Final discussion between Bonaparte and my father—Battle of Aboukir—My father finds treasure—His letter on this subject 161

CHAPTER V

Revolt at Cairo—My father enters the Grand Mosque on horseback—His home-sickness—He leaves Egypt and lands at Naples—Ferdinand and Caroline of Naples—Emma Lyon and Nelson—Ferdinand's manifesto—Comments of his minister, Belmonte-Pignatelli 172

CHAPTER VI

Report presented to the French Government by Divisional-General Alexandre Dumas, on his captivity at Taranto and at Brindisi, ports in the Kingdom of Naples 181

CHAPTER VII

My father is exchanged for General Mack—Events during his captivity—He asks in vain for a share in the distribution of the 500,000 francs indemnity granted to the prisoners—The arrears of his pay also refused him—He is placed on the retired list, in spite of his energetic protests 197

CHAPTER VIII

Letter from my father to General Brune on my birth—The postscript—My godfather and godmother—First recollections of infancy—Topography of the château des Fossés and sketches of some of its inhabitants—The snake and the frog—Why I asked Pierre if he could swim—Continuation of Jocrisse 204

CHAPTER IX

Mocquet's nightmare—His pipe—Mother Durand—Les bêtes fausses et le pierge—M. Collard—My father's remedy—Radical cure of Mocquet 212

CHAPTER X

Who was Berlick?—The fête of Villers-Cotterets—Faust and Polichinelle—The sabots—Journey to Paris—Dollé—Manette—Madame de Mauclerc's pension—Madame de Montesson—Paul and Virginia—Madame de Saint-Aubin 218

CHAPTER XI

Brune and Murat—The return to Villers-Cotterets—L'hôtel de l'Épée—Princess Pauline—The chase—The chief forester's permission—My father takes to his bed never to rise again—Delirium—The gold-headed cane—Death 225

CHAPTER XII

My love for my father—His love for me—I am taken away to my cousin Marianne's—Plan of the house—The forge—The apparition—I learn the death of my father—I wish to go to heaven to kill God—Our situation at the death of my father—Hatred of Bonaparte 232

BOOK III

CHAPTER I

My mother and I take refuge with my grandfather—Madame Darcourt's house—My first books and my first terrors—The park at Villers-Cotterets—M. Deviolaine and his family—The swarm of bees—The old cloister 243

CHAPTER II

The two snakes—M. de Valence and Madame de Montesson—Who little Hermine was—Garnier the wheelwright and Madame de Valence—Madame Lafarge—Fantastic apparition of Madame de Genlis 253

CHAPTER III

Mademoiselle Pivert—I make her read the Thousand and One Nights, or, rather, one story in that collection—Old Hiraux, my music-master—The little worries of his life—He takes his revenge on his persecutors after the fashion of the Maréchal de Montluc—He is condemned to be flogged, and nearly loses the sight of his eyes—What happened on Easter Day in the organ-loft at the monastery—He becomes a grocer's lad—His vocation leads him to the study of music—I have little aptitude for the violin 259

CHAPTER IV

The dog lantern-bearer—Demoustier's epitaph—My first fencing-master—"The king drinks"—The fourth terror of my life—The tub of honey 277

CHAPTER V

My horror of great heights—The Abbé Conseil—My opening at the Seminary—My mother, much pressed, decides to enter me there—The horn inkstand—Cécile at the grocer's—My flight 285

CHAPTER VI

The Abbé Grégoire's College—The reception I got there—The fountains play to celebrate my arrival—The conspiracy against me—Bligny challenges me to single combat—I win 295

CHAPTER VII

The Abbé Fortier—The jealous husband and the viaticum—A pleasant visit—Victor Letellier—The pocket-pistol—I terrify the population—Tournemolle is requisitioned—He disarms me 304

CHAPTER VIII

A political chronology—Trouble follows trouble—The fire at the farm at None—Death of Stanislas Picot—The hiding-place for the louis d'or—The Cossacks—The haricot mutton 315

CHAPTER IX

The quarry—Frenchmen eat the haricot cooked for the Cossacks—The Duc de Treviso—He allows himself to be surprised—Ducoudray the hosier—Terrors 324

CHAPTER X

The return to Villers-Cotterets, and what we met on the way—The box with the thirty louis in it—The leather-bag—The mole—Our departure—The journey—The arrival at Mensal and our sojourn their—King Joseph—The King of Rome—We leave Mensal—Our visit to Crispy in Valois—The dead and wounded—The surrender of Paris—The isle of Elba 331

CHAPTER XI

Am I to be called Davy de La Pailleterie or Alexandre Dumas?—Deus dedit, Deus dabit—The tobacco-shop—The cause of the Emperor Napoleon's fall, as it appeared to my writing-master—My first communion—How I prepared for it 345

BOOK IV

CHAPTER I

Auguste Lafarge—Bird-snaring on a large scale—A wonderful catch—An epigram—I wish to write French verses—My method of translating Virgil and Tacitus—Montanan—My political opinions 355

CHAPTER II

The single-barrelled gun—Quiot Biche—Biche and Boudoux compared—I become a poacher—It is proposed to issue a writ against me—Madame Darcourt as plenipotentiary—How it happened that Cretan's writ caused me no bother 363

CHAPTER III

Bonaparte's landing at the Gulf of Juan—Proclamations and Ordonnances—Louis XVIII. and M. de Vitrolles—Cornu the hatter—Newspaper information 374

CHAPTER IV

General Exelmans—His trial—The two brothers Lallemand—Their conspiracy—They are arrested and led through Villers-Cotterets—The affronts to which they were subjected 382

CHAPTER V

My mother and I conspire—The secret—M. Richard—La pistole and the pistols—The offer made to the brothers Lallemand in order to save them—They refuse—I meet one of them, twenty-eight years later, at the house of M. le duc de Cazes 389

CHAPTER VI

Napoleon and the Allies—The French army and the Emperor pass through Villers-Cotterets—Bearers of ill tidings 402

CHAPTER VII

Waterloo—The Élysée—La Malmaison 411

CHAPTER VIII

Cæsar—Charlemagne—Napoleon 421

CHAPTER IX

The rout—The haricot mutton reappears—M. Picot the lawyer—By diplomatic means, he persuades my mother to let me go shooting with him—I despise sleep, food and drink 427

CHAPTER X

Trapping larks—I wax strong in the matter of my compositions—The wounded partridge—I take the consequences whatever they are—The farm at Brassoire—M. Deviolaine's sally at the accouchement of his wife 435

CHAPTER XI

M. Moquet de Brassoire—The ambuscade—Three hares charge me—What prevents me from being the king of the battue—Because I did not take the bull by the horns, I just escape being disembowelled by it—Sabine and her puppies 441

BOOK V

CHAPTER I

The second period of my youth—Forest-keepers and sailors—Choron, Moinat, Mildet, Berthelin—La Maison-Neuve 449

CHAPTER II

Choron and the mad dog—Niquet, otherwise called Bobino—His mistress—The boar-hunt—The kill—Bobino's triumph—He is decorated—The boar which he had killed rises again 456

CHAPTER III

Boars and keepers—The bullet of Robin-des-Bois—The pork-butcher 464

CHAPTER IV

A wolf-hunt—Small towns—Choron's tragic death 474

CHAPTER V

My mother realises that I am fifteen years old, and that la marette and la pipée will not lead to a brilliant future for me—I enter the office of Me. Mennesson, notary, as errand-boy, otherwise guttersnipe—Me. Mennesson and his clerks—La Fontaine-Eau-Claire 483

CHAPTER VI

Who the assassin was and who the assassinated—Auguste Picot—Equality before the law—Last exploits of Marot—His execution 491

CHAPTER VII

Spring at Villers-Cotterets—Whitsuntide—The Abbé Grégoire invites me to dance with his niece—Red books—The Chevalier de Faublas—Laurence and Vittoria—A dandy of 1818 499

CHAPTER VIII

I leap the Haha—A slit follows—The two pairs of gloves—The quadrille—Fourcade's triumph—I pick up the crumbs—The waltz—The child becomes a man 508

ALEXANDRE DUMAS

BY ANDREW LANG

There is no real biography of Alexandre Dumas. Nobody has collected and sifted all his correspondence, tracked his every movement, and pursued him through newspapers and legal documents. Letters and other papers (if they have been preserved) should be as abundant in the case of Dumas as they are scanty in the case of Molière. But they are left to the dust of unsearched offices; and it is curious that in France so little has been systematically written about her most popular if not her greatest novelist. Many treatises on one or other point in the life and work of Dumas exist, but there is nothing like Boswell's Johnson or Lockhart's Scott. The Mémoires by the novelist himself cover only part of his career, Les Enfances Dumas; and they bear the same resemblance to a serious conscientious autobiography as Vingt Ans Après bears to Mr. Gardiner's History of England. They contain facts, indeed, but facts beheld through the radiant prismatic fancy of the author, who, if he had a good story to tell, dressed it up "with a cocked hat and a sword," as was the manner of an earlier novelist. The volumes of travel, and the delightful work on Dumas's domestic menagerie, Mes Bêtes, also contain personal confessions, as does the novel, Ange Pitou, with the Causeries, and other books. Fortunately Dumas wrote most about his early life, and the early life of most people is more interesting than the records of their later years.

In its limitation to his years of youth, the Mémoires of Dumas resemble that equally delightful book, the long autobiographical fragment by George Sand. Both may contain much Dichtung as well as Wahrheit: at least we see the youth of the great novelists as they liked to see it themselves. The Mémoires, with Mes Bêtes, possess this advantage over most of the books, that the most crabbed critic cannot say that Dumas did not write them himself. In these works, certainly, he was unaided by Maquet or any other collaborator. They are all his own, and the essential point of note is that they display all the humour, the goodness of heart, the overflowing joy in life, which make the charm of the novels. Here, unmixed, unadulterated, we have that essence of Dumas with which he transfigured the tame "copy" drawn up by Maquet and others under his direction. He told them where to find their historical materials, he gave them the leading ideas of the plot, told them how to block out the chapters, and then he took these chapters and infused into them his own spirit, the spirit which, in its pure shape, pervades every page of the Mémoires. They demonstrate that, while he received mechanical aid from collaborators, took from their hands the dry bones of his romances, it was he who made the dry bones live. He is now d'Artagnan, now Athos, now Gorenflot, now Chicot,—all these and many other personages are mere aspects of the immortal, the creative Alexandre.

Dumas's autobiography, as far as it is presented in this colossal fragment, does not carry us into the period of his great novels (1844-1850). Even this Porthos of the pen found the task of writing the whole of his autobiography trop lourd. The work (in how many volumes?) would have been monumental: he left his "star-y-pointing pyramid" incomplete, and no mortal can achieve the task which he left undone.

Despite his vanity, which was genial and humorous, Alexandre Dumas could never take himself seriously. This amiable failing is a mistake everywhere if a man wants to be taken seriously by a world wherein the majority have no sense of humour. The French are more eminent in wit; their masters of humour are Rabelais, Montaigne, Molière, Pascal, and, in modern times, Dumas, Théophile Gautier, and Charles de Bernard. Of these perhaps only two received fair recognition during their lives. Dumas, of course, was not unrecognised; few men of the pen have made more noise in the world. He knew many of the most distinguished people, from Victor Hugo and Louis Philippe to Garibaldi. Dickens he might have known, but when Dickens was in Paris Dumas invited him to be at a certain spot in the midnight hour, when a mysterious carriage would convey him to some place unnamed. Mr. R. L. Stevenson would have kept tryst, Dickens did not; he could not tell what prank this eternal boy had in his mind. Being of this humour, Dumas, however eminent his associates, however great the affairs in which he was concerned, always appeared to the world rather as Mousqueton than as Porthos, a tall man of his hands, indeed, but also much of a comic character, often something of a butt. Garrulous, gay, doing all things with emphasis and a flourish, treating a revolution much in the manner of comic opera, Dumas was not un homme sérieux. In literature it was the same. He could not help being merry; the world seemed a very jolly place to him; he never hooted, he said, at the great spectacle of the drama of Life.

His own extraordinary gifts of industry, knowledge, brilliance, ingenuity, sympathy, were playthings to him. He scattered wit as he scattered wealth, lavishly, with both hands, being so reckless that, on occasion, he would sign work into which he had put nothing of his own. To such a pitch did Dumas carry his lack of seriousness that the last quarter or more of his life makes rather sorry reading. "The chase of the crown piece" may be amusing in youth, but when middle age takes the field in pursuit of the evasive coin, the spectacle ceases to exhilarate. Dumas was really of a most generous nature, but he disregarded the Aristotelian mean—he was recklessly lavish. Consequently he was, of course, preyed upon by parasites of both sexes, odious hangers-on of literature, the drama, and the plastic arts. He, who could not turn away a stray self-invited dog, managed to endure persons rather worse than most of that strange class of human beings—the professional friends of men of genius. "What a set, what a world!" says Mr. Matthew Arnold, contemplating the Godwin circle that surrounded Shelley. "What a set!" expresses Lockhart's sentiments about certain friends of Sir Walter Scott. We cannot imagine why great men tolerate these people, but too often they do; a famous English poet was horrified by "those about" George Sand. The society which professionally swarmed round Dumas was worse—the cher maître was robbed on every hand. He "made himself a motley to the view," and as all this was at its worst after his great novels—with which we are chiefly concerned—were written, I intend to pass very lightly over the story of his decline.

The grandfather of Alexandre Dumas, Antoine Alexandre Davy de la Pailleterie, was more or less noble. It has not been my fortune to encounter the name of his family in the field of history. They may have "borne St. Louis company," or charged beneath the banner of the Maid at Orléans and Pathay; one can only remark that one never heard of them. The grandfather, at all events, went to San Domingo, and became the father, by a negro woman, of the father of the novelist. As it is hardly credible that he married his mistress, Marie Dumas, it is not clear how the great Alexandre had a right to a marquisate. On this point, however, he ought to have been better informed than we are, who have not seen his parchments. His father at all events, before 1789, enlisted in the army under the maternal name of Dumas. During the Revolution he rose to the rank of General. He was a kind of Porthos. Clasping his horse between his knees and seizing a beam overhead with his hands, he lifted the steed off the ground. Finding that a wall opposed a charge which he was leading, he threw his regiment, one by one, over the wall, and then climbed it himself. In 1792 he married the daughter of an innkeeper at Villers-Cotterets, a good wife to him and a good mother to his son. In Egypt he disliked the arbitrary proceedings of Napoleon, went home, and never was employed again. He had mitigated, as far as in him lay, the sanguinary ferocities of the Revolutionaries. A good man and a good sportsman, he died while Alexandre, born July 24th, 1802, was a little boy. The child had been sent to sleep at a house near his father's, and was awakened by a loud knock at the moment of the General's death. This corresponds to the knocks which herald deaths in the family of Woodd: they are on record in 1661, 1664, 1674, 1784, 1892, 1893, and 1895. Whether the phenomenon is hereditary in the House of la Pailleterie we are not informed. Dumas himself had a firm belief in his own powers as a hypnotist, but thought that little good came of hypnotism. Tennyson was in much the same case.

Madame Dumas was left very poor, and thought of bringing up her child as a candidate for holy orders. But Dumas had nothing of Aramis except his amorousness, and ran away into a local forest rather than take the first educational step towards the ecclesiastical profession. In later life he was no Voltairean, he held Voltaire very cheap, and he believed in the essentials of religion. But he was not built by lavish nature for the celibate life, though he may have exaggerated when he said that he had five hundred children. The boy, like most clever boys, was almost equally fond of books and of field sports. His education was casual; he had some Latin (more than most living English novelists) and a little German. Later he acquired Italian. His handwriting was excellent; his writing-master told him that Napoleon's illegible scrawls perplexed his generals, and certainly Napoleon wrote one of the worst hands in the world. Perhaps his orders to Grouchy, on June 17-18th, 1815, were indecipherable. At all events, Dumas saw the Emperor drive through Villers-Cotterets on June 12th, and drive back on June 20th. He had beaten the British at 5.30 on the 18th, says Dumas, but then Blücher came up at 6.30 and Napoleon ceased to be victorious. What the British were doing in the hour after their defeat Dumas does not explain, but he expresses a chivalrous admiration for their valour, especially for that of our Highlanders.

After the British defeat at Waterloo the world did not change much for a big noisy boy in a little country town. He was promoted to the use of a fowling-piece, and either game was plentiful in these days or the fancy of the quadroon rivalled that of Tartarin de Tarascon. Hares appear to have been treated as big game, the huntsman lying low in ambush while the doomed quarry fed up to him, when he fired, wounded the hare in the leg, ran after him, and embraced him in the manner of Mr. Briggs with his first salmon. The instinct of early genius, or rather of the parents of early genius, points direct to the office of the attorney, notary, or "writer." Like Scott and other immortals, Dumas, about sixteen or eighteen, went into a solicitor's office. He did not stay there long, as he and a friend, during their master's absence, poached their way to Paris, defraying their expenses by the partridges and hares which they bagged. Every boy is a poacher, but in mature life Dumas is said to have shot a large trout in Loch Zug—I find I have written; the Lake of Zug is meant. This is perhaps the darkest blot upon his fame.

His escapade to Paris was discovered by his employer, who hinted a dislike of such behaviour. The blood of de la Pailleterie was up, and Dumas resigned his clerkship. He had made at Villers-Cotterets the acquaintance of Auguste de Leuven, a noble Swede, "kept out of his own" for political reasons. De Leuven knew Paris and people about the theatres; he also tried his own hand at playwriting. Dumas in his society caught the stage fever, and he happened also to see the Hamlet of Ducis acted—a very French Hamlet, but Dumas divined somehow the greatness of Shakespeare through the veil of Ducis. He knew no more English than most Frenchmen of letters know. Like M. Jules Lemaître, he read Shakespeare and Scott, "in cribs," I suspect, but he read them with delight. Homer, too, he studied only in cribs, but he perceived the grandeur of the Greek epics, the feebleness of the cribs, and vowed that he would translate Homer himself. He did not, however, take the preliminary step of learning Greek. The French drama of the period is said by those who know it to have been a watery thing. The great old masters were out—Dumas and Hugo were not yet in. Dumas began by collaborating with young de Leuven in bright little patriotic pieces. Thus his earliest efforts were collaborative, as they continued to be, about which there is much to be said later. Just as Burns usually needed a keynote to be struck for him by an old song or a poem of young Fergusson's—by a predecessor of some sort—so Dumas appears to have needed companionship in composition. It is a curious mental phenomenon, for he had more ideas than anyone else. He could master a subject more rapidly for his purpose than anyone else, yet he required companionship, contact with other minds engaged on the same theme. I am apt to think that this was the result of the pre-eminently social nature of Dumas. Charles II., as we learn from Lord Ailesbury's Memoirs, could not bear to be alone, and must have Harry Killigrew to make him laugh, even on occasions when privacy is courted by mankind. Most people like to write alone; not so Dumas. Comradeship he must have, even in composing, and this, I conceive, was the true secret of his inveterate collaborativeness.

At all events, he began, as a lad, with de Leuven. Through him, after poaching his way to Paris for a day or two, he made the acquaintance of Talma, the famous actor. Returning to Paris after that escapade, he instantly became known to all sorts of useful and interesting people. This gift of making acquaintances stood him in great stead: one often wonders how it is done. In a recent biography of a Scot of letters we find the hero arriving in town, not, it would seem, an eminently attractive hero, but he is at once familiar with George Lewes, George Eliot, Tennyson, Browning, and other sommités. How is it done? Dumas's father had known General Foy, General Foy knew the Duc d'Orléans (Louis Philippe), and got a little clerkship in his service for the young quadroon. A few days later he goes to a play, and to whom must he sit next but Charles Nodier, then celebrated, and Nodier must be reading the Elzevir Pastissier Français, of which I doubt if a dozen copies are known to exist. How Nodier made friends with Dumas, and hissed his own play, is a most familiar anecdote. It sounds like a dream, a dream that came through the ivory gate. Shifted from one clerkship to another, now snubbed, now befriended by officials, Dumas did certainly read a great deal of modern literature at this time, especially Schiller and Scott. Without Scott he might never have written his great novels, for the idea of historical novels, based on a real knowledge of history, and on a vivid realisation of historical persons as actual men and women, is Sir Walter's own. Scott's daring and Turneresque composition was also bequeathed to Dumas. Sir Walter had no scruples about bringing Amy Robsart to life some fifteen years or more after her death, or about making Shakespeare a successful dramatist fifteen years before he came upon the town.

But plays, not novels, at this time occupied Dumas. Chance brought him acquainted with the history of Christine of Sweden, and with that of Henri III. of France. A little collaborative comedy was acted, a volume of contes was published, but was not purchased. A son was born to Dumas in 1824, the celebrated Alexandre Dumas fils, whose talent was so unlike that of his sire. The parent tried, with Soulié, to dramatise Old Mortality, to "Terrify" it, as Scott would have said. They did not finish their attempt, but Dumas now saw Shakespeare acted by Kemble, Liston, and an English company. He found out "what the theatre really was," and he proceeded to evolve many "parts to tear a cat in." More "in Ercles' vein" than in the vein of Shakespeare were the romantic plays which now arose in France: passions and violent scenes of intrigue were within the compass of Dumas: humour, too, he had, and great skill in effect and in charpentage. The style, the charm, the poetry, are absent, carmina desunt.

Christine and the murder of Monaldeschi furnished the first topic. After troubles and complications innumerable (there were three Christines in the field), Dumas's play was written, and re-constructed, and accepted. In the interval he had made, for the joy of mankind, the acquaintance of Henri III. and Saint-Mégrin, of Catherine de Medici and Chicot, and Guise, in the Mémoires of L'Estoile. The time was now 1828-30. Dumas left his official work; the authorities did not think him a model clerk, he was a good deal interrupted by actresses while Henri III. was being rehearsed. Just before the first night his mother suffered a shock of apoplexy; his attention was divided between the stage and her bedside. With colossal self-confidence, he invited the Duc d'Orléans to his play. The Due had a dinner-party, but what of that? The party must meet earlier; the play must begin earlier than the usual hours, and all the party must come. But the adventure of the Duchesse de Guise and Saint-Mégrin, the appearance of that Elagabalus of the Valois, Henri III., with his mignons, and cup and ball, his foppery and asceticism, thrilled and entertained a large and distinguished audience in the Théâtre Français. Dumas triumphed; unhappily his mother was unable to share his joy. His fortune was made, and he took pleasure in his publicity. He was probably better known for the time and more spoken of than Victor Hugo, whose really sonorous fame scarcely dates before the first night of Hernani.

Though Dumas thus led the Romantiques of 1830 through the breach, though he was first in the forlorn hope that took the acropolis of the old classical drama, one does not think of him as a Romantique. For one reason or another, he stands a little aloof from Hugo, Gautier, Alfred de Musset, and the set of Pétrus Borel, however intimate he may have been with Augustus Mackeat (Maquet).

Dumas's next play, "classical" in form, was Christine, the long-deferred Christine, for the Odéon. The anecdotes about the difficulties with the classical actress, Mile. Mars, are familiar. Dumas was now one of the most notable men in Paris, and in the July days of 1830 he added to his notoriety, conducting himself much like Mr. Jingle on the same historic occasion. He was prominent, with a fowling-piece, in the street-fighting, and it seems that he really did seize the powder magazine at Soissons, by that "native cheek" which never failed him at need. The details are as good as anything in his novels, but Dumas surely invented the lady who, beholding him armed with pistols, declared that it was "a revolt of the blacks." His unlucky colour and his crisp thick hair gave people so many opportunities for jests, that Dumas anticipated the world and made the jokes himself. Perhaps the accident of blood and complexion was one of the reasons that prevented him from taking himself seriously. We need not linger over his political adventures: they led him into La Vendée, where he found the elements of romance. Dumas, I think, was by nature as Royalist as Athos, who, in his advice to Raoul, expresses the very creed of the great Montrose. He ought to have fought for the Duchesse de Berry and the Queen of Naples, but circumstances threw him with the Orleanists and Garibaldi, though he loved Louis Philippe no more than other gentlemen did. He tried to be elected for the Assembly: he might as well have tried to get into the Academy, he was not un homme sérieux.

Dumas's career as a novelist was brightest in the forties of the nineteenth century. In the thirties he was much more occupied with plays, whereof Antony caused most noise. He went on producing plays of the most various types—he travelled, he married, but soon "went by," he made historical compilations, and glided into the field which chiefly concerns us, that of historical romance. Omitting Le Capitaine Paul (Paul Jones) of 1838, and Le Capitaine Pamphile, a most amusing book (1840), we find Le Chevalier d'Harmental (1843), Les Trois Mousquetaires (1844), Vingt Ans Après (1845), La Reine Margot (1845), Le Comte de Monte Cristo (1845), La Dame de Monsoreau (1846), Joseph Balsamo (1846-1848), Les Quarante Cinq (1848), Le Vicomte de Bragelonne (1848-1850), not to specify dozens of others, including unavailing things like Jeanne d'Arc, charming things like La Tulipe Noire, and the novels on the Regency, and the long series on the French Revolution.

Consider the novels of 1844-1850. The Mousquetaire cycle, the Valois cycle, Monte Cristo! Did Scott, or even Dickens, at their best and most prolific, ever equal this rate of production? Perhaps we must give the prize to Scott for the work of 1814-1820, including Waverley, The Antiquary, Old Mortality, The Heart of Midlothian, Rob Roy, and so on. That record cannot be broken, and Scott worked in his odd hours, or in his holidays, while he worked alone. But in all the great novels of Dumas, Maquet, the ci-devant Augustus Mackeat, collaborated. Yet who can deny that the work is the work of the Dumas of the Mémoires and of Mes Bêtes? It is the same hand, the same informing spirit, the same brilliant gaiety, the same honest ethics, the same dazzling fertility of resource. Maquet did something—there is no doubt on that head, the men constantly worked together.

But what did Maquet do? He may have made—he did make—"researches." Heaven knows that they were not very deep. Perhaps he discovered that Newcastle is on the Tweed, and that the Scottish army which—shall we say did not adhere to Charles I.?—largely consisted of Highlanders. Perhaps he suggested that Charles I. might want to hear a Mass on the eve of his execution. Perhaps he depicted jolly Charles II. as un beau ténébreux, in the Vicomte de Bragelonne. I think that there I find the hand of Maquet. Whatever he did, Maquet did something. I suggest that he made these remarkable researches, that he listened while Dumas talked, that he "made objections" (as the père invited the fils to do), that sometimes he "blocked out" a chapter, which Dumas took, and made into a new thing, or left standing, like that deplorable Charles II. at Blois. On the whole, I conceive that (as regards the great novels) Maquet satisfied Dumas's need of companionship, that he was to the man of genius what Harry Killigrew was to the actual Charles II.

Before the law, in 1856 and in 1858, M. Maquet claimed his right to be declared fellow-author of eighteen novels, all the best of them. It was recognised by the law that he had lent a hand, but he took no more than that by his legal adventures. M. Glinel publishes two of his letters to his counsel: "It is not justice which has won the day, but Dumas," exclaims Augustus. He also complains that he is threatened with a new law-suit "avec l'éternel coquin qu'on appelle Dumas." Time kills many animosities. According to M. About, M. Maquet lived to speak kindly of Dumas, as did his legion of other collaborators. "The proudest congratulate themselves on having been trained in so good a school; and M. Auguste Maquet, the chief of them, speaks with real reverence and affection of his great friend." Monsieur Henri Blaze de Bury describes Dumas's method thus:—

"The plot was considered by Dumas and his assistant. The collaborator wrote the book and brought it to the master, who worked over the draft, and re-wrote it all. From one volume, often ill-constructed, he would evolve three volumes or four. Le Chevalier d'Harmental by Maquet at first was a tale of sixty pages. Often and often Dumas was the unnamed collaborator of others." M. Blaze de Bury has seen a score of pieces, signed by other names, of which Dumas in each case wrote two-thirds. M. About confirms M. Blaze de Bury's account. He has known Dumas give the ideas to his collaborator. That gentleman then handed in a sketch, written on small leaves of paper. Dumas copied each leaf out on large paper, expanding, altering, improving, en y semant l'esprit à pleines mains.

By this method of collaboration Dumas really did the work himself. He supplied the ideas and the esprit, and gave the collaborator a lesson in the art of fiction, much as a tutor teaches composition in Greek or Latin. In other examples, such as Le Chevalier d'Harmental, the idea, we know, came from Maquet, who had written a conte on the subject. Nobody wanted the conte, and Dumas made it into the novel, whereby Maquet also benefited. In England collaboration in novel-writing is unusual. In the case of Mr. Rice and Sir Walter Besant we have Sir Walter's description of "how it was done," and it appears that he did most of it. In another case familiar to me, A, an unpopular author, found in his researches a good and dramatic historical subject. On this he wrote a tale of seven chapters, and placed that tale in a drawer, where it lay for years. He then showed it to B, who made a play out of it. The play was nibbled at, but not accepted. B then took the subject, and, going behind the original story, worked up to the point at which it began, whence B and A continued it, and now the thing was a novel, which did not rival in popularity the works of Dumas. Probably in each case of collaboration the methods differ. In one case each author wrote the whole of the book separately, and then the versions were blended.

These are legitimate practices, but in his later years Dumas became less conscientious. There is a story, we have seen, that Maquet once inserted sixteen ques in one sentence, and showed it to his friends. Dumas never looked at it, and the sentence with its sixteen ques duly appeared in the feuilleton of next day's newspaper, for in newspapers were the romances "serialised," as some literary journals say. I have never found that sentence in any of the novels, never met more than five ques in one sentence of Dumas's, or more than five "whiches" in one of Sir Walter Scott's. As his age and indolence increased, the nature of things revenged itself on the fame and fortunes of Dumas. The author of the later novels, as M. Henri Blaze de Bury says, is "Dumas-Légion."

The true collaborators of Dumas were human nature and history. Men are eternally interesting to men, but in historical writing, before Scott, the men (except the kings and other chief actors) were left much in the vague. They and their deeds and characters lay hidden in memoirs and unprinted letters. Such a man as the Cavalier, Edward Wogan, "a very beautiful person," says Clarendon, was briefly and inaccurately touched on by that noble author. More justice is done to him by his kinsman, the adventurous Sir Charles Wogan, in a letter to Swift. He did not escape Scott, who wrote a poem to his memory. Now, such a character as Wogan, brave, beautiful, resourceful as d'Artagnan, landing in England with the gallows before his eyes, and carrying a troop of cavalry through the hostile Cromwellian country, "wherever might lead him the shade of Montrose," to join the Clans and strike a blow for King Charles, was precisely the character for Dumas. Such men as Wogan, such women as Jane Lane and Lady Ogilvy, Dumas rediscovered, and they were his inspiration. The past was not really dull, though dull might be the books of academic historians. They omitted the human element, the life, the colour, and, we are told, "scientific history" ought to be thus impartially jejune. The great public turns away from scientific history to Dumas and to modern imitators, good and bad, and how inordinately bad some of his followers can be! An American critic half despairs of his country because some silly novels, pretending to be historical, are popular. The symptom is good rather than bad. Untrained and undirected, falling on the stupid and ignorant new novels most loudly trumpeted, the young Americans do emancipate themselves from the tyranny of to-day, and their own fancy lends a glamour to some inept romance of the past. They dwell with tragedy and with Mary Stuart, though she be the Mary Stuart of a dull, incompetent scribbler. They may hear of Scott and Dumas, and follow them.

Dumas has been blamed by moralists like Mr. Fitzgerald for depraving the morals of France! That he set an example of violence and frenzy, crime and licence on the stage, cannot easily be denied. But in the Musketeers he decidedly improves on the taste and morals of the France of 1630-1660, whether tested by d'Artagnan's Mémoires or by the more authentic works of Tallemant and de Retz. He is infinitely more delicate, he apologises for what he justly calls the "infamies" of certain proceedings of his heroes, and he puts heart and sentiment even into the light love of Milady's soubrette. If d'Artagnan "had no youth, no heart, only ambition," he acquires a heart as he goes on: and, indeed, never lacked one—for friends of his own sex.

Dumas was at the opposite pole from a Galahad or a Joseph. His life, as regards women, was much like that of Burns or Byron. His morality on this point is that of the camp or of the theatre in which he lived so much. This must be granted as an undeniable fact. But there are other departments of conduct, and in the virtues of courage, devotion, fortitude, friendship, and loyalty, the Musketeers are rich enough. Their vices, happily, are not those of our age but of one much less sensitive on certain points of honour, as Dumas remarks, and as history proves. But the virtues of the Musketeers are, in any age, no bad example.

Dumas never writes to inflame the passions, to corrupt, or to instruct a prurient curiosity. The standard of his work is far higher than that of his model or of the age about which he writes. His motto is sursum corda; he has not a word to encourage pessimism, or a taste for the squalid. He and his men face Fortune boldly, bearing what mortals must endure, and bearing it well and gaily. His ethics are saved by his humour, generosity, and sound-hearted humanity. These qualities increase and become more manifest as this great cycle rolls on to its heroic culmination in the death of d'Artagnan, the death of Porthos, the unwonted tears of Aramis.

For many years "high sniffing" French critics have sneered at Dumas as a scene-painter, a dauber, a babe in psychological lore, and so forth. But of late we have seen in the success of M. Rostand's Cyrano de Bergerac, that France looks lovingly back on her old ideals of a frank and healthy life in the open air—a life of gallant swordsmen, kind friends, and true lovers. In Major Marchand, of the Fashoda affair, we may recognise a gentleman and soldier of the school of Dumas, not of Maupassant, or Flaubert, or Zola. To know his task and to do it despite the most cruel obstacles; to face every form of peril with gaiety; to accept disappointment with a manly courtesy, winning the heartiest admiration from his political opponents, these are accomplishments after Dumas's own heart; and this is a morality which the study of Dumas encourages, and which our time requires.

The authors who relax, and discourage, and deprave may be thought better artists (an opinion which I do not share), but they are less of men than the author of The Three Musketeers. Who reads it, but wants to go on reading the sequel, and the sequel to that, and, were it possible, yet another sequel? But Aramis alone of the four is left on the stage, and we pine for another sequel—with Aramis as Pope.

I have dwelt on the Musketeers and their historical sources as a type of the powers and methods of Dumas. As much might be said in detail as to the sources of the other great novels, especially those of the Valois circle. History gives little more than the name of Chicot, and his ferocity in the St. Bartholomew massacres. La Mole, Coconnas, and le brave Bussy, were really "rather beasts than otherwise," as the lad in Mr. Eden Philpotts's Human Boy says about pirates. Catherine de Medici is the Catherine of the Mémoires, which are probably truthful on the whole, whatever criticism may say. Dumas fills with gaiety these old times of perfidy and cruelty; he adds Gorenflot and Chicot; he humanises Coconnas; he even inspires regret for Henri III.; he has a Shakespearean love and tolerance for his characters. The critics may and do sniff, but Dumas pleased George Sand, Thackeray, and Mr. Stevenson, who have praised him so well that feebler plaudits are impertinent, Thackeray especially chooses La Tulipe Noire as a complement and contrast to the Musketeers. Monte Cristo, rich and revengeful, has never been my favourite; I leave him when his treasure hunt is ended, and the Cagliostro cycle deals with matters too cruel for fiction.

In brief, though the rest of the life of Dumas was full of labour, the anni mirabiles of 1844-1850 are the prime of his harvests. In 1844, on a tour with the son of Jérôme Napoleon (who certainly had a strange bear-leader), Dumas saw the actual isle of Monte Cristo; it dwelt in his boyish fancy, and became the earliest of all Treasure Islands; but its use as the first part of a tale in the manner of Eugène Sue was an afterthought—like the American scenes and Mrs. Gamp in Martin Chuzzlewit. In 1843-44, Dumas, being rich, built his Abbotsford, Monte Cristo, between Saint Germain and Marly le Roi. Thenceforth it was the farce of which the real Abbotsford is the tragedy. It was open house and endless guests, very unlike the guests who visited the villa on the Tweed. At both houses many dogs were kept, at Monte Cristo only were piles of gold left lying about for everyone to help himself. The Théâtre Historique was also founded, that road to ruin Dumas could not leave untrodden, and he abandoned all his schemes to visit Spain and Algiers with the Duc de Montpensier, like Buckingham with Prince Charles. The celebrated vulture, Jugurtha, was now acquired and brought home, to fill his niche in the gallery of Mes Bêtes, one of the most delightful books in the world.

On returning Dumas found, like Odysseus, "troubles in his house," angry editors clamorous for belated "copy." Then came the parasites, and then the Revolution of 1848, exciting but expensive to a political man of letters. The Théâtre Historique was ruined, and Dumas chose another path to financial collapse, the ownership of a newspaper. In 1851 Dumas went to Brussels, quarrelled with Maquet (one creditor among many), wrote his Mémoires, tried to retrench, but embarked on a new newspaper, Le Mousquetaire. He was the reverse of a man of business; Le Mousquetaire was not profitable like Household Words. The office was a bear garden. More plays were written, more of every kind of thing was written, a weekly paper was attempted, and as the star of Alexandre fils was rising, the star of Alexandre père descended through shady spaces of the sky. Dumas travelled in Russia, and wrote about that; he joined Garibaldi in 1860, and obtained in Italy an archæological appointment! The populace of Naples did not take Dumas seriously, any more than the staff of the British Museum would have done. For reasons known or unknown to the mob they hooted and threatened the Director of Excavations: the editor of a Garibaldian newspaper, the father of the god-daughter of Garibaldi, a child whose mother had accompanied Dumas in the costume of a sailor. At this time the hero was fifty-eight, and perhaps the Neapolitans detected some incongruity between the age and the proceedings of the Director of Excavations. Perhaps la vertu va se nicher in the hearts of the lower classes of "the great sinful streets" of the city of Neapolis.

In 1864 Dumas and the new Italian Government were not on harmonious terms. He left his Liberal newspaper and his meritorious excavations in Pompeii; he returned to Paris accompanied by a lady bearing the pleasing name of Fanny Gordosa. The gordosiousness, if I may use the term, of Fanny far exceeded her capacities as a housekeeper and domestic manager, and the undefeated veteran had to pursue that hunt for the pièce de cent sous whereof we have spoken. La jeunesse n'a qu'un temps, but Dumas was determined "to be boy for ever." Stories are told about him which, whether they be true or untrue, are better unrepeated. Senile boyishness, where the sex is concerned, cannot be seemly. Money became more scarce as work ceased to be genuine work. Dumas fell to giving public lectures. A daughter came to attend him, as the Duchess of Albany presided over and more or less reformed the last years of her royal father. In 1869-70 the strength of this Porthos of the pen was broken: c'est trop lourd! In the autumn of 1870, about the time of the disaster of Sedan, the younger Dumas carried his father to a village near Dieppe. They kept from him the sorrows of these days: his mind dwelt with the past and the dead. He died on December 5th, and on the same day, at Dieppe, the Germans reached the sea. His body lies at Villers-Cotterets, beside his father and mother.

ANDREW LANG.

THE MEMOIRS OF ALEXANDRE DUMAS

BOOK I

CHAPTER I

My birth—My name is disputed—Extracts from the official registers of Villers-Cotterets—Corbeil Club—My father's marriage certificate—My mother—My maternal grandfather—Louis-Philippe d'Orléans, father of Philippe-Égalité—Madame de Montesson—M. de Noailles and the Academy—A morganatic marriage.

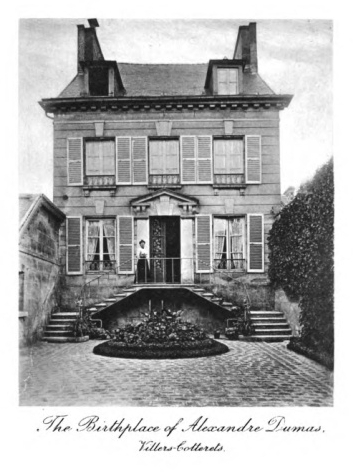

I was born at Villers-Cotterets, a small town in the department of Aisne, situated on the road between Paris and Laon, about two hundred paces from the rue de la Noue, where Demoustier died; two leagues from La Ferté-Milon, where Racine was born; and seven leagues from Château-Thierry, the birthplace of La Fontaine.

I was born on the 24th of July 1802, in the rue de Lormet, in the house now belonging to my friend Cartier. He will certainly have to sell it me some day, so that I may die in the same room in which I was born. I will step forward into the darkness of the other world in the place that received me when I stepped into this world from the darkness of the past.

I was born July 24th, 1802, at half-past five in the morning; which fact makes me out to be forty-five years and three months old at the date I begin these Memoirs—namely, on Monday, October the 18th, 1847.

Most facts concerning my life have been disputed, even my very name of Davy de la Pailleterie, which I am not very tenacious about, since I have never borne it. It will only be found after my name of Dumas in official deeds that I have executed before a lawyer, or in civil actions wherein I played either the principal part or was a witness.

I therefore ask permission to transcribe my birth certificate, to allay any further discussion upon the subject.

Extract from the Registers of the Town of Villers-Cotterets.

"On the fifth day of the month of Thermidor, year X of the French Republic.

"Certificate of the birth of Alexandre Dumas-Davy de la Pailleterie, born this day at half-past five in the morning, son of Thomas-Alexandre Dumas-Davy de la Pailleterie, lieutenant-general, born at Jérémie, on the coast of the island of Saint-Domingo, dwelling at Villers-Cotterets; and of Marie-Louise-Élisabeth Labouret, born at the above-mentioned Villers-Cotterets, his wife.

"The sex of the child is notified to be male.

"First witness: Claude Labouret, maternal grandfather of the child.

"Second witness: Jean-Michel Deviolaine, inspector of forests in the fourth communal arrondissement of the department of Aisne, twenty-sixth jurisdiction, dwelling at the above mentioned Villers-Cotterets. This statement has been made to us by the father of the child, and is signed by

"Al. Dumas, Labouret, and Deviolaine.

"Proved according to the law by me Nicolas Brice-Mussart, mayor of the town of Villers-Cotterets, in his capacity as official of the Civil State,

Signed: MUSSART."

I have italicised the words his wife, because those who contested my right to the name of Davy de la Pailleterie sought to prove that I was illegitimate.

Now, had I been illegitimate I should quietly have accepted the bar as more celebrated bastards than I have done, and, like them, I should have laboured arduously with mind or body until I had succeeded in giving a personal value to my name. But what is to be done, gentlemen? I am not illegitimate, and it is high time the public followed my lead—and resigned itself to my legitimacy.

They next fell back upon my father. In a club at Corbeil—it was in 1848—there lived an extremely well-dressed gentleman, forsooth, whom I was informed belonged to the magistracy; a fact which I should never have believed had I not been assured of it by trustworthy people; well, this gentleman had read, in I know not what biography, that it was not I but my father who was a bastard, and he told me the reason why I never signed myself by my name of Davy de la Pailleterie was because my father was never really called by that name, since he was not the son of the marquis de la Pailleterie.

I began by calling this gentleman by the name usually applied to people who tell you such things; but, as he seemed quite as insensible to it as though it had been his family name, I wrote to Villers-Cotterets for a second birth certificate referring to my father, similar to the one they had already sent me about myself.

I now ask the reader's permission to lay this second certificate before him; if he have the bad taste to prefer our prose to that of the secretary to the mayoralty of Villers-Cotterets, let him thrash the matter out with this gentleman of Corbeil.[1]

Certificate of Birth from, the Registers of the Town of Villers-Cotterets.

"In the year 1792, first of the French Republic, on the 28th of the month of November, at eight o'clock at night, after the publication of banns put up at the main door of the Town Hall, on Sunday the 18th of the present month, and affixed there ever since that date for the purpose of proclaiming the intended marriage between citizen Thomas-Alexandre Davy de la Pailleterie, aged thirty years and eight months, colonel in the hussars du Midi, born at la Guinodée, Trou-Jérémie, America, son of the late Alexandre-Antoine Davy de la Pailleterie, formerly commissary of artillery, who died at Saint-Germain en Laye, June 1786, and of the late Marie-Cessette Dumas, who died at la Guinodée, near Trou-Jérémie, America, in 1772; his father and mother, of the one part;

"And citizen Marie-Louise-Élisabeth Labouret, eldest daughter of citizen Claude Labouret, commandant of the National Guard of Villers-Cotterets and proprietor of the hôtel de l'Écu, and of Marie-Joseph Prévot, her father and mother, of the other part;

"The said domiciled persons, namely, the future husband in barracks at Amiens and the future wife in this town; their birth certificates having also been inspected and naught being found wrong therein; I, Alexandre-Auguste-Nicolas Longpré, public and municipal officer of this commune, the undersigned, having received the declaration of marriage of the aforesaid parties, have pronounced in the name of the law that they are united in marriage. This act has taken place in the presence of citizens: Louis-Brigitte-Auguste Espagne, lieutenant-colonel of the 7th regiment of hussars stationed at Cambrai, a native of Audi, in the department of Gers;

"Jean-Jacques-Étienne de Béze, lieutenant in the same regiment of hussars, native of Clamercy, department of la Nièvre;

"Jean-Michel Deviolaine, registrar of the corporation and a leading citizen of this town, all three friends of the husband;

"Françoise-Élisabeth Retou, mother-in-law of the husband, widow of the late Antoine-Alexandre Davy de la Pailleterie, dwelling at Saint-Germain en Laye.

"Present, the father and mother of the bride, all of age, who, together with the contracting parties, have signed their hands to this deed in our presence:

"Signed at the registry:

"MARIE LOUISE ÉLISABETH LABOURET; THOMAS-ALEXANDRE DUMAS-DAVY DE LA PAILLETERIE; widow of LA PAILLETERIE; LABOURET; MARIE-JOSEPH PRÉVOT; L. A. ESPAGNE; JEAN-JACQUES-ÉTIENNE DE BÉZE; JEAN-MICHEL DEVIOLAINE, and LONGPRÉ, Public Officer."

Having settled that neither my father nor I were bastards, and reserving to myself to prove at the close of this chapter that my grandfather was no more illegitimate than we, I will continue.

My mother, Marie-Louise-Élisabeth Labouret, was the daughter of Claude Labouret, as we saw, commandant of the National Guard and proprietor of the hôtel de l'Écu, at the time he signed his daughter's marriage contract, but formerly first steward of Louis-Philippe d'Orléans, son of that Louis d'Orléans who made so little noise, and father of Philippe-Joseph, later known as Philippe-Égalité, who made so much!

Louis-Philippe died of an attack of gout, at the castle of Sainte-Assise, November the 18th, 1785. The Abbé Maury, who quarrelled so violently in 1791 with the son, had in 1786 pronounced the funeral oration over the father at Nôtre-Dame.

I recollect having often heard my grandfather speak of that prince as an excellent and on the whole a charitable man, though inclined to avarice. But far before all others my grandfather worshipped Madame de Montesson to the verge of idolatry.

We know how Louis-Philippe d'Orléans, left a widower after his first marriage with that famous Louise-Henriette de Bourbon-Conti, whose licentiousness had scandalised even the Court of Louis XV., had, on April the 24th, 1775, married as his second wife Charlotte-Jeanne Béraud de la Haie de Riou, marquise de Montesson, who in 1769 had been left the widow of the marquis de Montesson, lieutenant of the king's armies.

This marriage, although it was kept secret, was made with the consent of Louis XV. Soulavie gives some curious details about its celebration and accomplishment which are of sufficient interest to confide to these pages.

We feel sure these details are not unwelcome now that manners have become so different from what they then were.

Let us first impress upon our readers that Madame de Montesson was supposed by Court and town to hold the extraordinary notion of not wishing to become the wife of M. le duc d'Orléans until after he had married her.

M. de Noailles has since written a book which opened the doors of the Academy to him, upon the resistance of Madame de Maintenon to the solicitations of Louis XIV. under similar circumstances.

Behold on what slight causes depends the homogeneity of incorporated associations! If the widow Scarron had not been a maid at the time of her second marriage, which was quite possible, M. de Noailles would not have written his book, and the Academy, which felt the need of M. de Noailles' presence, would have remained incomplete, and in consequence imperfect.

That would not have mattered to M. de Noailles, who would always have remained M. de Noailles.

But what would have become of the Academy?

But let us return to M. le duc d'Orléans, to his marriage with Madame de Montesson, and to Soulavie's anecdote, which we will reproduce in his own words.

"The Court and capital were aware of the tortures endured by the duc d'Orléans and of Madame de Montesson's strictness.

"The love-lorn prince scarcely ever encountered the king or the duc de Choiseul without renewing his request to be allowed to marry Madame de Montesson.

"But the king had made it a matter of state policy not to allow either his natural children or those of the princes to be legitimatised, and this rule was adhered to throughout his reign.

"For the same reasons he refused the nobility of the realm permission to contract marriages with princes of the blood.

"The interminable contentions between the lawful princes and those legitimatised by Louis XIV., the dangerous intrigues of M. de Maine and of Madame de Maintenon, were the latest examples cited to serve as a motive for the refusals with which the king and his ministers confronted M. le duc d'Orléans. The royal blood of the house of Bourbon was still considered divine, and to contaminate it was held a political crime.

"In the South the house of Bourbon was allied on the side of Henry IV., the Béarnais prince, to several inferior noble families. The house of Bourbon did not recognise such alliances, and if any gentleman not well versed in these matters attempted to support them it was quite a sufficient ground for excluding him from Court favour.

"Moreover, the minister was so certain of maintaining supremacy over the Orléans family, that Louis XV. steadfastly refused to make Madame de Montesson the first princess of the blood by a solemn marriage, forcing the duc d'Orléans to be contented with a secret marriage. This marriage, although a lawful, conjugal union, was not allowed any of the distinctions belonging to marriages of princes of the blood, and was not to be made public.

"Madame de Montesson had no ambition to play the part of first princess of the blood against the king's wishes, nor yet to keep up hostilities over matters of etiquette with the princesses: it was not in her nature to do so.

"Already accustomed to observe the rules of modesty with M. le duc d'Orléans, she seemed quite content to marry him in the same way that Madame de Maintenon had married Louis XIV.

"The Archbishop of Paris was informed of the king's consent, and allowed the pair exemption from the threefold publication of their banns.

"The chevalier de Durfort, first gentleman of the chamber to the prince, by reversion from the comte de Pons, and Périgny, the prince's friend, were witnesses to the marriage, which was blessed by the Abbé Poupart, curé de Saint-Eustache, in the presence of M. de Beaumont, archbishop of Paris.

"On his wedding-day the duc d'Orléans held a very large Court at Villers-Cotterets.

"The previous evening, and again on the morning of the ceremony, he told M. de Valençay and his most intimate friends that he had reached at last an epoch in his life, and that his present happiness had but the single drawback that it could not be made public.

"On the morning of the day when he received the nuptial benediction at Paris he said:

"'I leave society, but I shall return to it again later; I shall not return alone, but accompanied by a lady to whom you will show that attachment you now bear towards myself and my interests.'

"The Castle was in the greatest state of expectation all that day; for M. d'Orléans going away without uttering the word Marriage had taken the key to the mysteries of that day.

"At night they saw him re-enter the crowded reception chamber, leading by the hand Madame de Montesson, upon whom all looks were fixed.

"Modesty was the most attractive of her charms; all the company were touched by her momentary embarrassment.

"The marquis de Valençay advanced to her and, treating her with the deference and submission due to a princess of the blood, did the honours of the house as one initiated in the mysteries of the morning.

"The hour for retiring arrived.

"It was the custom with the king and in the establishments of the princes for the highest nobleman to receive the night robe from the hands of the valet-de-chambre and to present it to the prince when he went to bed: at Court, the prerogative of giving it to the king belonged to the first prince of the blood; in his own palace he received it from the first chamberlain.

"Madame de Sévigné says in a letter dated 17th of January 1680 that:

"'In royal marriages the newly wedded couple were put to bed and their night robes given them by the king and queen. When Louis XIV. had given his to M. le prince de Conti, and the queen hers to the princess, the king kissed her tenderly when she was in bed, and begged her not to oppose M. le prince de Conti in any way, but to be obedient and submissive.'

"At M. le duc d'Orléans' wedding the ceremony of the night robe took place after this fashion. There was some embarrassment just at first, the duc d'Orléans and the marquis de Valençay temporising for a few moments, the former before asking for it, the latter before receiving it.

"M. d'Orléans bore himself as a man who prided himself upon his moderation in the most lawful of pleasures.

"Valençay at length presented it to the prince, who, stripping off his day vestments to the waist, afforded to all the company a view of his hairless skin, an example of the fashion indulged in by the highest foppery of the times.

"Princes or great noblemen would not consummate their marriages, nor receive first favours from a mistress, until after they had submitted to this preliminary operation.

"The news of this fact immediately spread throughout the room and over the palace, and it put an end to any doubts of the marriage between the duc d'Orléans and Madame de Montesson, over which there had been so much controversy and opposition.

"After his marriage the duc d'Orléans lived in the closest intimacy with his wife, she paying him unreservedly the homage due to the first prince of the blood.

"In public she addressed him as Monseigneur, and spoke with due respect to the princesses of the blood, ceding them their customary precedence, whether in their exits or their entrances, and during their visits to the state apartments of the Palais-Royal.

"She maintained her name as the widow of M. de Montesson; her husband called her Madame de Montesson or simply madame, occasionally my wife, according to circumstances. He addressed her thus in the presence of his friends, who often heard him say to her as he withdrew from their company: 'My wife, shall we now go to bed?'

"Madame de Montesson's sterling character was for long the source of the prince's happiness, his real happiness.

"She devoted her days to the study of music and of hunting, which pastime she shared with the prince. She also had a theatre in the house she inhabited in the Chaussée d'Antin, on the stage of which she often acted with him.

"The duc d'Orléans was naturally good-natured and simple in his tastes, and the part of a peasant fitted him; while Madame de Montesson played well in the rôles of shepherdess and lover.

"The late duchesse d'Orléans had degraded the character of this house to such a degree that no ladies entered it save with the utmost and constant wariness. Madame de Montesson re-established its high tone and dignity; she opened the way to refined pleasures, awakened interest in intellectual tastes and the fine arts, and brought back once more a spirit of gaiety and good fellowship."

Sainte-Assise and this château at Villers-Cotterets wherein, as related by Soulavie, this ardently desired marriage was brought about, were both residences belonging to the duc d'Orléans.

The château had been part of the inheritance of the family since the marriage of Monsieur, brother of King Louis XIV., with Henrietta of England.

The edifice, which was almost as large as the town itself, became a workhouse, and is now a home of refuge for seven or eight hundred poor people. There is nothing remarkable about it from an architectural point of view, except one corner of the ancient chapel, which belongs, so far as one can judge from the little that remains, to the finest period of the Renaissance. The castle was begun by François I. and finished by Henri II.

Both father and son set their own marks on it.

François I. carved salamanders on it, and Henri II. his coat of arms with that of his wife, Katherine de Médicis.

The two arms are composed of the letters K and H, and are encircled in the three crescents of Diane de Poitiers.

A curious intermingling of the arms of the married wife and of the mistress is still visible in the corner of the prison which overlooks the little lane that leads to the drinking trough.

We must here point out that Madame de Montesson was the aunt of Madame de Genlis, and through her influence it was that the author of Adèle et Théodore entered the house of Madame la duchesse d'Orléans, wife of Philippe-Joseph, as maid of honour; a post which led to her becoming the mistress of Philippe-Égalité, and governess to the three young princes, the duc de Valois, the duc de Montpensier and the comte de Beaujolais. The duc de Valois became duc de Chartres upon the death of his grandfather, and, on the 9th of August 1830, he became Louis Philippe I., to-day King of the French.

[1] We ought to say that this incident, which occurred in 1848, is interpolated in MS. written in 1847.

CHAPTER II

My father—His birth—The arms of the family—The serpents of Jamaica—The alligators of St. Domingo—My grandfather—A young man's adventure—A first duel—M. le duc de Richelieu acts as second for my father—My father enlists as a private soldier—He changes his name—Death of my grandfather—His death certificate.

My father, who has already been mentioned twice in the beginning of this history—first with reference to my birth certificate and later in connection with his own marriage contract—was the Republican General Thomas-Alexandre Dumas-Davy de la Pailleterie.

As already stated in the documents quoted by us, he was himself the son of the marquis Antoine-Alexandre Davy de la Pailleterie, colonel and commissary-general of artillery, and he inherited the estate of la Pailleterie, which had been raised to a marquisate by Louis XIV., in 1707.

The arms of the family were three eagles azure with wings spread or, two wings across one, one with a ring argent in the middle; clasped left and right by the talons of the eagles at the head of the escutcheon and reposing on the crest of the remaining eagle.

To these arms, my father, when enlisting as a private, added a motto, or rather, he took it in place of his arms when he renounced his title: this was "Deus dedit, Deus dabit"; a device which would have been presumptuous had not Providence countersigned it.

I am unaware what Court quarrel or speculative motive decided my grandfather to leave France, about the year 1760, and to sell his property and to go and establish himself in St. Domingo.

With this end in view he had purchased a large tract of land at the eastern side of the island, close to Cape Rose, and known under the name of la Guinodée, near Trou-Jérémie.

Here, on March 25th, 1762, my father was born—the son of Louise-Cessette Dumas and of the marquis de la Pailleterie.

The marquis de la Pailleterie, born in 1710, was then fifty-two years old.

My father's eyes opened on the most beautiful scenery of that glorious island, the queen of the gulf in which it lies, the air of which is so pure that it is said no venomous reptile can live there.

A general, sent to re-conquer the island, when we had lost it, hit upon the ingenious idea of importing from Jamaica into St. Domingo a whole cargo of the deadliest reptiles that could be found, as auxiliaries. Negro snake-charmers were commissioned to take them up at the one island and to set them free on the other.

Tradition has it that a month afterwards every one of the snakes had perished.

St. Domingo, then, possesses neither the black snake of Java, nor the rattlesnake of North America, nor the hooded cobra of the Cape; but St. Domingo has alligators.

I recollect hearing my father relate—when I must have been quite a young child, since he died in 1806 and I was born in 1802—I recollect, I say, hearing my father relate, that one day, when he was ten years old, and was returning from the town to his home, when he saw to his great surprise an object that looked like a tree-trunk lying on the sea-shore. He had not noticed it when he passed the same place two hours before; and he amused himself by picking up pebbles and throwing them at the log; when, suddenly, at the touch of the pebbles, the log woke up.

The log was an alligator dozing in the sun. Now alligators, it seems, wake up in most unpleasant tempers; this one spied my father and started to run after him. My father was a true son of the Colonies, a son of the seashores and of the savannas, and knew how to run fast; but it would seem that the alligator ran or rather jumped still faster than he, and this adventure bid fair to have left me for ever in limbo, had not a negro, who was sitting astride a wall eating sweet potatoes, noticed what was happening, and cried out to my already breathless father:

"Run to the right, little sah; run to the left, little sah."

Which, translated, meant, "Run zigzag, young gentleman," a style of locomotion entirely repugnant to the alligator's mechanism, who can only run straight ahead of him, or leap lizard-wise.

Thanks to this advice, my father reached home safe and sound; but, when there, he fell, panting and breathless, like the Greek from Marathon, and, like him, was very nearly past getting up again.

This race, wherein the beast was hunter and the human being the hunted, left a deep impression on my father's mind.

My grandfather, brought up in the aristocratic circle of Versailles, had little taste for a colonist's mode of life: moreover, his wife, to whom he had been warmly attached, had died in 1772; and as she managed the estate it deteriorated in value daily after her death. The marquis leased the estate for a rent to be paid him regularly, and returned to France.

This return took place about the year 1780, when my father was eighteen years of age.

In the midst of the gilded youth of that period, the Fayettes, the Lameths, the Dillons, the Lazuns, who were all his companions, my father lived in the style of a gentleman's son. Handsome in looks, although his mulatto complexion gave him a curiously foreign appearance; as graceful as a Creole, with a good figure at a time when a well-set-up figure was thought much of, and with hands and feet like a woman's; amazingly agile at all physical exercises, and one of the most promising pupils of the first fencing-master of his time—Laboissière; struggling for supremacy in dexterity and agility with St. Georges, who, although forty-eight years old, laid claim to be still a young man and fully justified his pretensions, it was to be expected that my father would have a host of adventures, and he had: we will only repeat one, which deserves that distinction on account of its original character.

Moreover, a celebrated name is connected with it, and this name appears so often in my dramas or in my novels that it seems almost my duty to explain to the public how I came to have such a predilection for it.

The marquis de la Pailleterie had been a comrade of the duc de Richelieu, and was, at the time of this anecdote, his senior by fourteen years; he commanded a brigade at the siege of Philipsbourg in 1738, under the marquis d'Asfeld.

My grandfather was then first gentleman to the prince de Conti.

As is generally known, the duc de Richelieu was, on his grandfather's side (whose name was Vignerot), of quite low descent.

He had foolishly changed the t of the ending of his name to d, to confute pedigree hunters by making them think it was of English origin. These heraldic grubbers claimed that the name Vignerot with a t and not with a d at the end of it had originally sprung from a lute player, who had seduced the great Cardinal's niece, as did Abelard the niece of Canon Fulbert; but, more lucky than Abelard, he finished his course by marrying her after he had seduced her.

The marshal—who at this time was not yet made a marshal—was, by his father, a Vignerot, and only on his grandmother's side a Richelieu. This did not, however, prevent him from taking for his first wife Mademoiselle de Noailles, and for his second Mademoiselle de Guise, the latter alliance connecting him with the imperial house of Austria, and making him cousin to the prince de Pont and the prince de Lixen.

Now it fell out one day that the duc de Richelieu had an attack of colic, and therefore had not taken the usual pains with his toilet; it fell out, I say, that he returned to the camp with my grandfather, and went out hunting, covered with sweat and mud all over.

The princes de Pont and de Lixen were hunting at the same time, and the duke, who was in haste to return home to change his clothes, passed by them at a gallop and saluted them.

"Oh! oh!" said the prince de Lixen, "is that you, cousin? How muddy you are! But perhaps you are a little bit cleaner since you married my cousin."

M. de Richelieu pulled up his horse and leapt to the ground, motioning to my grandfather to do the same, and he advanced to the prince de Lixen:

"Sir," said he, "you did me the honour to address me."

"Yes, M. le duc," replied the prince.

"I am afraid I misunderstood the words you did me the honour to address to me. Will you have the goodness to repeat them to me exactly as you said them?"

The prince de Lixen bowed his head in the affirmative, and repeated word for word the phrase he had uttered.

It was so insolently done that there was no way out of it. M. de Richelieu bowed to the prince de Lixen and clapped his hand to his sword.

The prince followed suit.

The prince de Pont naturally was obliged to be his brother's second, and my grandfather Richelieu's.

A minute later M. de Richelieu plunged his sword through the body of the prince de Lixen, who fell back stone dead into the arms of the prince de Pont.[1]