The Caravaners

Elizabeth Von Arnim

THE CARAVANERS

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Elizabeth and Her German Garden

Adventures of Elizabeth in Rügen

Fräulein Schmidt and Mr. Anstruther

Princess Priscilla’s Fortnight

The Solitary Summer

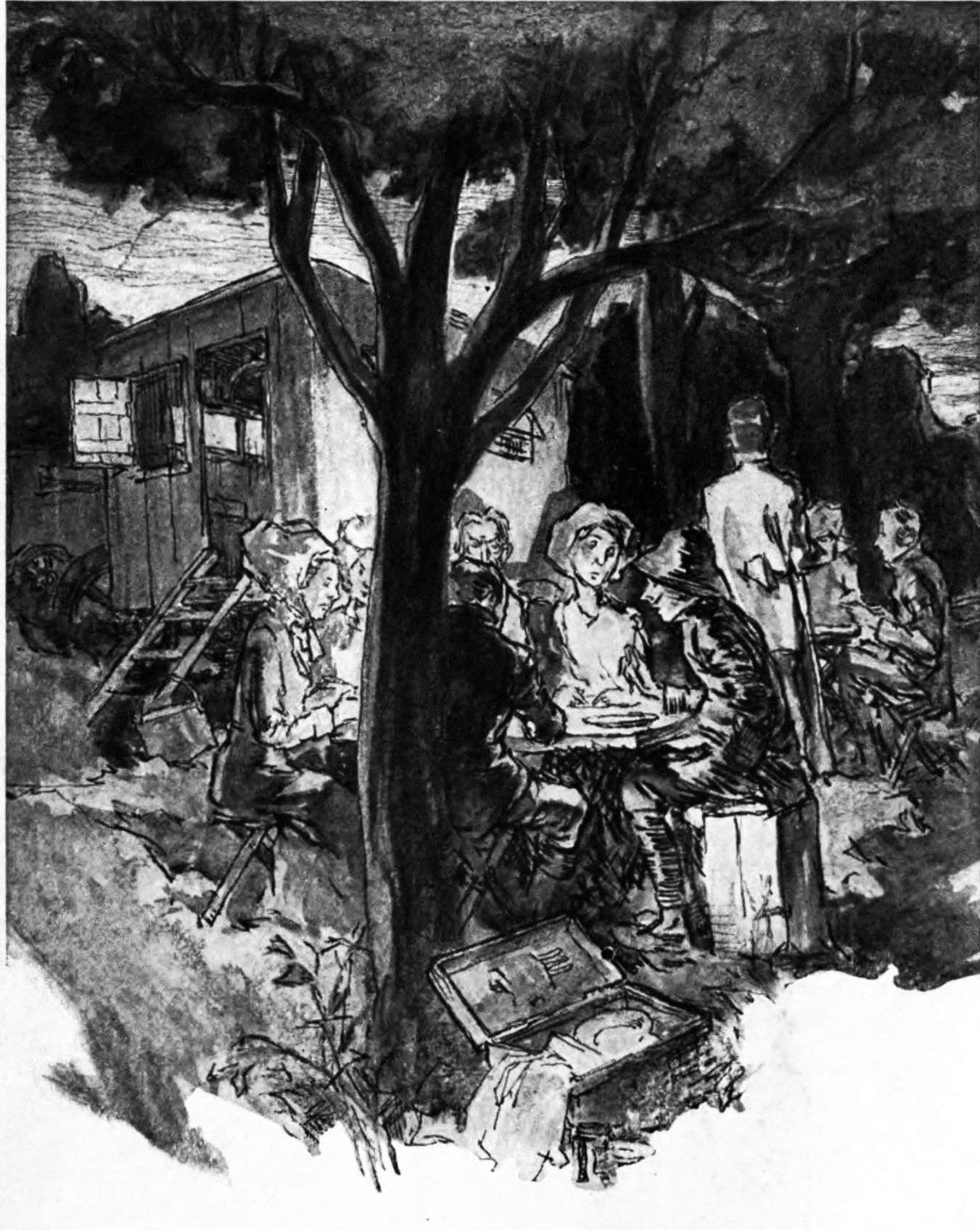

The fitful flicker of the lanterns played over rapidly cooling eggs and grave faces

THE CARAVANERS

BY THE AUTHOR OF

“ELIZABETH AND HER GERMAN GARDEN”

ILLUSTRATIONS BY ARTHUR LITLE

NEW YORK

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

1910

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, INCLUDING THAT OF TRANSLATION

INTO FOREIGN LANGUAGES, INCLUDING THE SCANDINAVIAN

COPYRIGHT, 1909, BY DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

ILLUSTRATIONS

| The fitful flicker of the lanterns played over rapidly cooling eggs and grave faces | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| I never saw such little shoes | 14 |

| Edelgard most inconsiderately leaving me to bear the entire burden of opening and shutting our things | 38 |

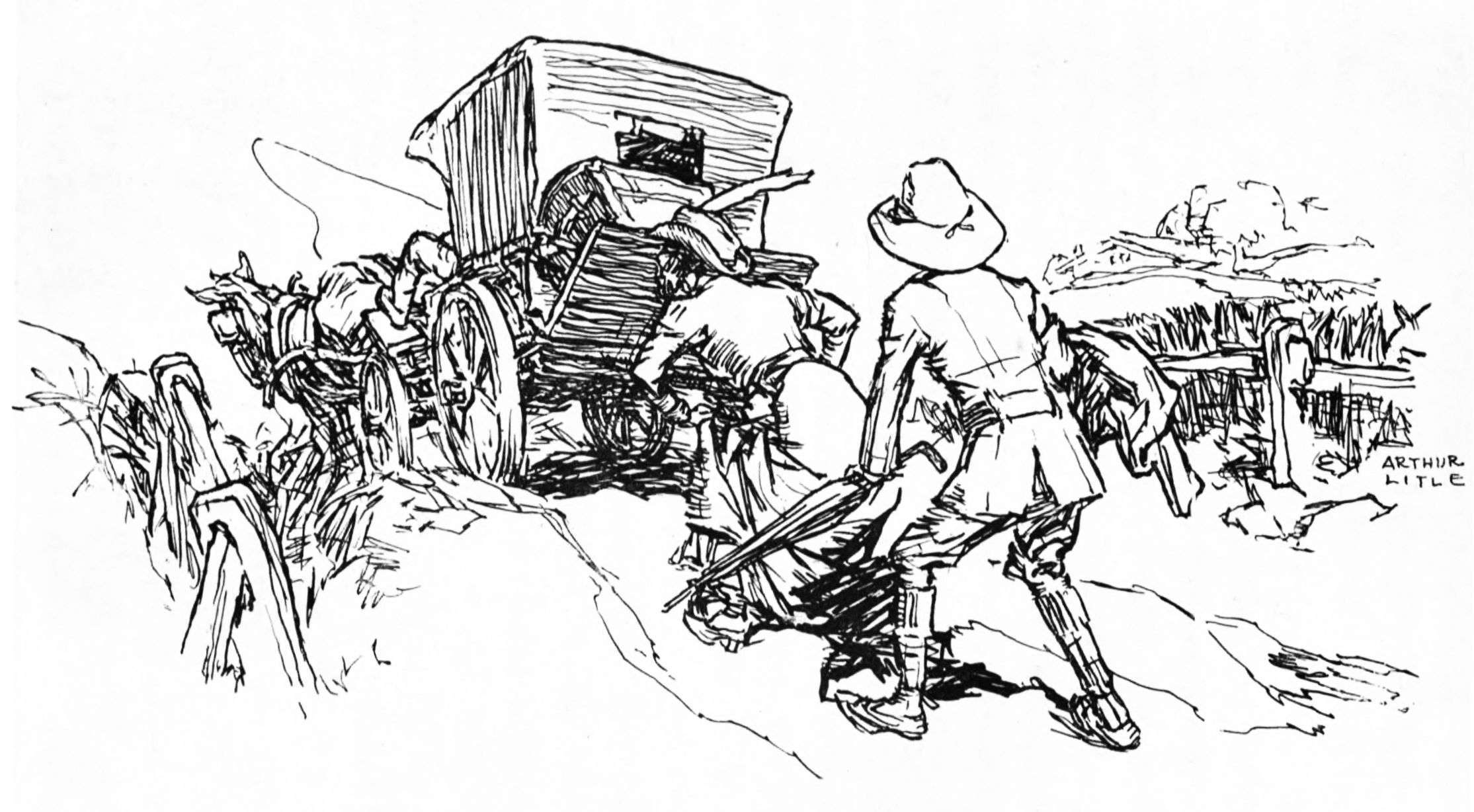

| The sun shone its hottest while we slowly surmounted this last obstacle | 50 |

| It was an unnerving spectacle | 80 |

| “Dear Baron,” said she, “do you think it is wrong to carry stew-pots?” | 100 |

| Thus, as it were, with blacking, did I cement my friendship with Lord Sigismund | 102 |

| Edelgard posing—and what a pose; good heavens, what a pose! | 114 |

| “But surely not here,” murmured Frau von Eckthum | 124 |

| The two nondescripts, who were passing, lingered to look | 134 |

| “But, lieber Otto, is it then my fault that you have forgotten the paper?” | 142 |

| “Do you, Jellaby,” I then inquired, “really understand how best to treat a sausage?” | 182 |

| “’Ere ’e is” | 200 |

| An imposing lady in the pew in front of us sat sideways in her corner and examined us with calm attention | 230 |

| The old gentleman was in the act of addressing me in his turn | 268 |

| Gentle as my voice was, it yet made her start | 294 |

THE CARAVANERS

CHAPTER I

IN JUNE this year there were a few fine days, and we supposed the summer had really come at last. The effect was to make us feel our flat (which is really a very nice, well-planned one on the second floor at the corner overlooking the cemetery, and not at all stuffy) but a dull place after all, and think with something like longing of the country. It was the year of the fifth anniversary of our wedding, and having decided to mark the occasion by a trip abroad in the proper holiday season of August we could not afford, neither did we desire, to spend money on trips into the country in June. My wife, therefore, suggested that we should devote a few afternoons to a series of short excursions within a radius of, say, from five to ten miles round our town, and visit one after the other those of our acquaintances who live near enough to Storchwerder and farm their own estates. “In this way,” said she, “we shall get much fresh air at little cost.”

After a time I agreed. Not immediately, of course, for a reasonable man will take care to consider the suggestions made by his wife from every point of view before consenting to follow them or allowing her to follow them. Women do not reason: they have instincts; and instincts would land them in strange places sometimes if it were not that their husbands are there to illuminate the path for them and behave, if one may so express it, as a kind of guiding and very clever glow-worm. As for those who have not succeeded in getting husbands, the flotsam and jetsam, so to speak, of their sex, all I can say is, God help them.

There was nothing, however, to be advanced against Edelgard’s idea in this case; on the contrary, there was much to commend it. We should get fresh air; we should be fed (well fed, and, if we chose, to excess, but of course we know how to be reasonable); and we should pay nothing. As Major of the artillery regiment stationed at Storchwerder I am obliged anyhow to keep a couple of horses (they are fed at the cost of the regiment), and I also in the natural order of things have one of the men of my battalion in my flat as servant and coachman, who costs me little more than his keep and may not give me notice. All, then, that was wanting was a vehicle, and we could, as Edelgard pointed out, easily borrow our Colonel’s wagonette for a few afternoons, so there was our equipage complete, and without spending a penny.

The estates round Storchwerder are big and we found on counting up that five calls would cover the entire circle of our country acquaintance. There might have been a sixth, but for reasons with which I entirely concurred my dear wife did not choose to include it. Lines have to be drawn, and I do not think an altogether bad definition of a gentleman or a lady would be one who draws them. Indeed, Edelgard was in some doubt as to whether there should be even five, a member of the five (not in this case actually the land-owner but the brother of the widowed lady owning it, who lives with her and looks after her interests) being a person we neither of us can care much about, because he is not only unsound politically, with a decided leaning disgraceful in a man of his birth and which he hardly takes any trouble to hide toward those views the middle classes and Socialist sort of people call (God save the mark!) enlightened, but he is also either unable or unwilling—Edelgard and I could never make up our minds which—to keep his sister in order. Yet to keep the woman one is responsible for in order whether she be sister, or wife, or mother, or daughter, or even under certain favourable conditions aunt (a difficult race sometimes, as may be seen by the case of Edelgard’s Aunt Bockhügel, of whom perhaps more later) is really quite easy. It is only a question of beginning in time, as you mean to go on in fact, and of being especially firm whenever you feel internally least so. It is so easy that I never could understand the difficulty. It is so easy that when my wife at this point brought me my eleven o’clock bread and ham and butter and interrupted me by looking over my shoulder, I smiled up at her, my thoughts still running on this theme, and taking the hand that put down the plate said, “Is it not, dear wife?”

“Is what not?” she asked—rather stupidly I thought, for she had read what I had written to the end; then without giving me time to reply she said, “Are you not going to write the story of our experiences in England after all, Otto?”

“Certainly,” said I.

“To lend round among our relations next winter?”

“Certainly,” said I.

“Then had you not better begin?”

“Dear wife,” said I, “it is what I am doing.”

“Then,” said she, “do not waste time going off the rails.”

And sitting down in the window she resumed her work of enlarging the armholes of my shirts.

This, I may remark, was tartness. Before she went to England she was never tart. However, let me continue.

I wonder what she means by rails. (I shall revise all this, of course, and no doubt will strike out portions) I wonder if she means I ought to begin with my name and address. It seems unnecessary, for I am naturally as well known to persons in Storchwerder as the postman. On the other hand this is my first attempt (which explains why I wonder at all what Edelgard may or may not mean, beginners doing well, I suppose, to be humble) at what poetic and literary and other persons of bad form call, I believe, wooing the Muse. What an expression! And I wonder what Muse. I would like to ask Edelgard whether she—but no, it would almost seem as if I were seeking her advice, which is a reversing of the proper relative positions of husband and wife. So at this point, instead of adopting a course so easily disastrous, I turned my head and said quietly:

“Dear wife, our English experiences did begin with our visits to the neighbours. If it had not been for those visits we would probably not last summer have seen Frau von Eckthum at all, and if we had not come within reach of her persuasive tongue we would have gone on our silver wedding journey to Italy or Switzerland, as we had so often planned, and left that accursed island across the Channel alone.”

I paused; and as Edelgard said nothing, which is what she says when she is unconvinced, I continued with the patience I always show her up to the point at which it would become weakness, to explain the difference between the exact and thorough methods of men, their liking for going to the root of a matter and beginning at the real beginning, and the jumping tendencies of women, who jump to things such as conclusions without paying the least heed to all the important places they have passed over while they were, so to speak, in the air.

“But we get there first,” said Edelgard.

I frowned a little. A few months ago—before, that is, our time on British soil—she would not have made such a retort. She used never to retort, and the harmony of our wedded life was consequently unclouded. I think she saw me frown but she took no notice—another novelty in her behaviour; so, after waiting a moment, I determined to continue the narrative.

But before I go straight on with it I should like to explain why we, an officer and his wife who naturally do not like spending money, should have contemplated so costly a holiday as a trip abroad. The fact is, for a long time past we had made up our minds to do so in the fifth year of our marriage, and for the following reason: Before I married Edelgard I had been a widower for one year, and before being a widower I was married for no fewer than nineteen years. This sounds as though I must be old, but I need not tell my readers who see me constantly that I am not. The best of all witnesses are the eyes; also, I began my marrying unusually young. My first wife was one of the Mecklenburg Lunewitzes, the elder (and infinitely superior) branch. If she had lived, I would last year have been celebrating our silver wedding on August 1st, and there would have been much feasting and merry-making arranged for us, and many acceptable gifts in silver from our relations, friends, and acquaintances. The regiment would have been obliged to recognize it, and perhaps our two servants would have clubbed together and expressed their devotion in a metal form. All this I feel I have missed, and through no fault of my own. I fail to see why I should be deprived of every benefit of such a celebration, for have I not, with an interruption of twelve months forced upon me, been actually married twenty-five years? And why, because my poor Marie-Luise was unable to go on living, should I have to attain to the very high number of (practically) five and twenty years’ matrimony without the least notice being taken of it? I had been explaining this to Edelgard for a long time, and the nearer the date drew on which in the natural order of things I would have been reaping a silver harvest and have been put in a position to gauge the esteem in which I was held, the more emphatic did I become. Edelgard seemed at first unable to understand, but she was very teachable, and gradually found my logic irresistible. Indeed, once she grasped the point she was even more strongly of opinion than I was that something ought to be done to mark the occasion, and quite saw that if Marie-Luise failed me it was not my fault, and that I at least had done my part and gone on steadily being married ever since. From recognizing this to being indignant that our friends would probably take no notice of the anniversary was but, for her, a step; and many were the talks we had together on the subject, and many the suggestions we both of us made for bringing our friends round to our point of view. We finally decided that, however much they might ignore it, we ourselves would do what was right, and accordingly we planned a silver-honeymoon trip to the land proper to romance, Italy, beginning it on the first of August, which was the date of my marriage twenty-five years before with Marie-Luise.

I have gone into this matter at some length because I wished to explain clearly to those of our relations who will have this lent to them why we undertook a journey so, in the ordinary course of things, extravagant; and having, I hope, done this satisfactorily, will now proceed with the narrative.

We borrowed the Colonel’s wagonette; I wrote five letters announcing our visit and asking (a mere formality, of course) if it would be agreeable; the answers arrived assuring us in every tone of well-bred enthusiasm that it would; I donned my parade uniform; Edelgard put on her new summer finery; we gave careful instructions to Clothilde, our cook, helping her to carry them out by locking everything up; and off we started in holiday spirits, driven by my orderly, Hermann, and watched by the whole street.

At each house we were received with becoming hospitality. They were all families of our own standing, members of that chivalrous, God-fearing and well-born band that upholds the best traditions of the Fatherland and gathers in spirit if not (owing to circumstances) in body, like a protecting phalanx around our Emperor’s throne. First we had coffee and cakes and a variety of sandwiches (at one of the houses there were no sandwiches, only cakes, and we both discussed this unaccountable omission during the drive home); then I was taken to view the pigs by our host, or the cows, or whatever happened to be his special pride, but in four cases out of the five it was pigs, and while I was away Edelgard sat on the lawn or the terrace or wherever the family usually sat (only one had a terrace) and conversed on subjects interesting to women-folk, such as Clothilde and Hermann and I know not what; then, after having thoroughly exhausted the pigs and been in my turn thoroughly exhausted by them, for naturally a Prussian officer on active service cannot be expected to take the same interest in these creatures so long as they are raw as a man does who devotes his life to them, we rejoined the ladies and strolled in the lighter talk suited to our listeners about the grounds, endeavouring with our handkerchiefs to drive away the mosquitoes, till summoned to supper; and after supper, which usually consisted of one excellent hot dish and a variety of cold ones, preceded by bouillon in cups and followed by some elegant sweet and beautiful fruit (except at Frau von Eckthum’s, our local young widow’s, where it was a regular dinner of six or seven courses, she being what is known as ultra-modern, her sister having married an Englishman), after supper, I repeat, having sat a while smoking on the lawn or terrace drinking coffee and liqueurs and secretly congratulating ourselves on not having in our town to live with so many and such hungry mosquitoes, we took our leave and drove back to Storchwerder, refreshed always and sometimes pleased as well.

The last of these visits was to Frau von Eckthum and her brother Graf Flitz von Flitzburg, who, as is well known, being himself unmarried, lives with her and looks after the estate left by the deceased Eckthum, thereby stepping into shoes so comfortable that they may more properly be spoken of as slippers. All had gone well up to that, nor was I conscious till much later that that had not gone well too; for only on looking back do we see the distance we have come and the way in which the road, at first so promising, led us before we knew where we were into a wilderness plentiful in stones. During our first four visits we had naturally talked about our plan to take a trip in August in Italy. Our friends, obviously surprised, and with the expression on their faces that has its source in thoughts of legacies, first enthusiastically applauded and then pointed out that it would be hot. August, they said, would be an impossible month in Italy: go where we would we should not meet a single German. This had not struck us before, and after our first disappointment we willingly listened to their advice rather to choose Switzerland, with its excellent hotels and crowds of our countrymen. Several times in the course of these conversations did we try to explain the honeymoon nature of the journey, but were met with so much of what I strongly suspect to have been wilful obtuseness that to our chagrin we began to see there was probably nothing to be done. Edelgard said she wished it would occur to them if, owing to the unusual circumstances, they did not intend to give us actual ash-trays and match-boxes, to join together in defraying the cost of the wedding journey of such respectable silver-honeymooners; but I do not think that at any time they had the least intention of doing anything at all for us—on the contrary, they made us quite uneasy by the sums they declared we would have to disburse; and on our last visit (to Frau von Eckthum) happening to bewail the amount of good German money that was going to be dragged out of us by the rascally Swiss, she (Frau von Eckthum) said, “Why not come to England?”

At the moment I was so much engaged mentally reprobating the way in which she was lying back in a low garden chair with one foot crossed over the other and both feet encased in such thin stockings that they might just as well not have been stockings at all, that I did not immediately notice the otherwise striking expression, “Come.” “Go” would of course have been the usual and expected form; but the substitution, I repeat, escaped me at the moment because of my attention being otherwise engaged. I never

I never saw such little shoes

saw such little shoes. Has a woman a right to be conspicuous at the extremities? So conspicuous—Frau von Eckthum’s hands also easily become absorbing—that one is unable connectedly to follow the conversation? I doubt it: but she is an attractive lady. There sat Edelgard, straight and seemly, the perfect flower of a stricter type of virtuous German womanhood, her feet properly placed side by side on the grass and clothed, as I knew, in decent wool with the flat-heeled boots of the Christian gentlewoman, and I must say the type—in one’s wife, that is—is preferable. I rather wondered whether Flitz noticed the contrast between the two ladies. I glanced at him, but his face was as usual a complete blank. I wondered whether he could or could not make his sister sit up if he had wished to; and for the hundredth time I felt I never could really like the man, for from the point of view of a brother one’s sister should certainly sit up. She is, however, an attractive lady: alas that her stockings should be so persistently thin.

“England,” I heard Edelgard saying, “is not, I think, a suitable place.”

It was then that I consciously noticed that Frau von Eckthum had said “Come.”

“Why not?” she asked; and her simple way of asking questions, or answering them with others of her own without waiting to adorn them or round them off with the title of the person addressed, has helped, I know, to make her unpopular in Storchwerder society.

“I have heard,” said Edelgard cautiously, no doubt bearing in mind that to hosts whose sister had married an Englishman and was still living with him one would not say all one would like to about it, “I have heard that it is not a place to go to if the object is scenery.”

“Oh?” said Frau von Eckthum. Then she added—intelligently, I thought—“But there always is scenery.”

“Edelgard means lofty scenery,” said I gently, for we were both holding cups of the Eckthum tea (this was the only house in which we were made to drink tea instead of our aromatic and far more filling national beverage) in our hands, and I have always held one ought to humour the persons whose hospitality one happens to be enjoying—“Or enduring,” said Edelgard cleverly when, on our way home, I mentioned this to her.

“Or enduring,” I agreed after a slight pause, forced on reflection to see that it is not true hospitality to oblige your visitors to go without their coffee by employing the unworthy and barbarically simple expedient of not allowing it to appear. But of course that was Flitz. He behaves, I think, much too much as though the place belonged to him.

Flitz, who knows England well, having spent several years there at our Embassy, said it was the most delightful country in the world. The unpatriotic implication contained in this assertion caused Edelgard and myself to exchange glances, and no doubt she was thinking, as I was, that it would be a sad and bad day for Prussia if many of its gentleman had sisters who made misguided marriages with foreigners, the foreign brother-in-law being so often the thin end of that wedge which at its thick one is a denial of our right to regard ourselves as specially raised by Almighty God to occupy the first place among the nations, and a dislike (I have heard with my own ears a man at a meeting express it) an actual dislike—I can only call it hideous—of the glorious cement of blood and iron by means of which we intend to stick there.

“But I was chiefly thinking,” said Frau von Eckthum, her head well back in the cushions and her eyes fixed pensively on the summer clouds sailing over our heads, “of what you were saying about expense.”

“Dear lady,” I said, “I have been told by all who have done it that travelling in England is the most expensive holiday you can take. The hotels are ruinous as well as bad, the meals are uneatable as well as dear, the cabs cost you a fortune, and the inhabitants are rude.”

I spoke with heat, because I was roused (justly) by Flitz’s unpatriotic attitude, but it was a tempered heat owing to the undoubted (Storchwerder cannot deny it) personal attractiveness of our hostess. Why are not all women attractive? What habitual lambs our sex would become if they were.

“Dear Baron,” said she in her pretty, gentle voice, “do come over and see for yourself. I would like, I think, to convert you. Look at this”—she picked up some papers lying on the grass by her chair, and spreading out one showed me a picture—“do you not think it nice? And, if you want to be economical, it only costs fourteen pounds for a whole month.”

The picture she held out to me was one bearing a strong resemblance to the gipsy carts that are continually (and very rightly) being sent somewhere else by our local police; a little less gaudy perhaps, a little squarer and more solid, but undoubtedly a near relation.

“It is a caravan,” said Frau von Eckthum, in answer to the question contained in my eyebrows; and turning the sheet she showed me another picture representing the same vehicle’s inside.

Edelgard got up and looked over my shoulder.

What we saw was certainly very nice. Edelgard said so at once. There were flowered curtains, and a shelf with books, and a comfortable chair with a cushion near a big window, and at the end two pretty beds placed one above the other as in a ship.

“A thing like this,” said Frau von Eckthum, “does away at once with hotels, waiters, and expense. It costs fourteen pounds for two persons for a whole month, and all your days are spent in the sun.”

She then explained her plan, which was to hire one of these vehicles for the month of August and lead a completely free and bohemian existence during that time, wandering through the English lanes, which she described as flowery, and drawing up for the night in a secluded spot near some little streamlet, to the music of whose gentle rippling, as Edelgard always easily inclined to sentiment suggested, she would probably be lulled to sleep.

“Come too,” said she, smiling up at us as we looked over her shoulder.

“Two hundred and eighty marks is fourteen pounds,” said I, making mental calculations.

“For two people,” said Edelgard, obviously doing the same.

“No hotels,” said our hostess.

“No hotels,” echoed Edelgard.

“Only lovely green fields,” said our hostess.

“And no waiters,” said Edelgard.

“Yes, no horrid waiters,” said our hostess.

“Waiters are so expensive,” said Edelgard.

“You wouldn’t see one,” said our hostess. “Only a nice child in a clean apron from a farm bringing eggs and cream. And you move about the whole time, and see the country in a way you never would going from place to place by train.”

“But,” said I shrewdly, “if we move about something must either pull or push us, and that something must also be paid for.”

“Oh, yes, there has to be a horse. But think of all the railway tickets you won’t buy and all the porters you won’t tip,” said Frau von Eckthum.

Edelgard was manifestly impressed. Indeed, we both were. If it were a question of being in England for little money or being in Switzerland for much we felt unanimously that it was better to be in England. And then to travel through it in one of these conveyances was so distinctly original that we would be objects of the liveliest interest during the succeeding winter gaieties in Storchwerder. “The von Ottringels are certainly all that is most modern,” we could already hear our friends saying to each other, and could already see in our mind’s eye how they would press round us at soirées and bombard us with questions. We should be the centre of attraction.

“And think of the nightingales!” cried Edelgard, suddenly recollecting those poetic birds.

“In August they’re like Germans in Italy,” said Flitz, to whom I had mentioned our reason for giving up the idea of travelling in that country.

“How so?” said Edelgard, turning to him with the slight instinctive stiffening of every really virtuous German lady when speaking to an unrelated (by blood) man.

“They’re not there,” said Flitz.

Well, of course the moment we were able to look in our Encyclopædia at home we knew as well as he did that they do not sing in August, but I do not see how townsfolk are to keep these odds and ends of information lying loose about in their heads. We do not have the bird in Storchwerder and are therefore unable to study its habits at first hand as Flitz can, but I know that all the pieces of poetry I have come across mention nightingales before they have done, and the consequent perfectly natural impression left on my mind was that they were always more or less about. But I do not like Flitz’s tone, and never shall. It is true I have not actually seen him do it, but one feels instinctively that he is laughing at one; and there are different ways of laughing, and not all of them appear on the face. As for politics, if I were not as an officer debarred from alluding to them and were led to discuss them with him, I have no doubt that each discussion would end in a duel. That is, if he would fight. The appalling suspicion has just crossed my mind that he would not. He is one of those dreadful persons who cloak their cowardice behind the garb of philosophy. Well, well, I see I am growing angry with a man ten miles away, whom I have not seen for months—I, a man of the world sitting in the calm of my own flat, surrounded by quiet domestic objects such as my wife, my shirt, and my little meal of bread and ham. Is this reasonable? Certainly not. Let me change the subject.

The long, then, and the short of our visit to Graf Flitz and his sister in June last was that we returned home determined to join Frau von Eckthum’s party, and not a little full of pleasurable anticipations. When she does talk she has a persuasive tongue. She talked more at this time than she ever did afterward, but of course there were reasons for that which I may or may not disclose. Edelgard listened with something like rapt interest to her really picturesque descriptions, or rather prophecies, for she had not herself done it before, of the pleasures of camp life; and I wish it to be clearly understood that Edelgard, who has since taken the line of telling people it was I, was the one who was swept off her usually cautious feet and who took it upon herself without waiting for me to speak to ask Frau von Eckthum to write and hire another of the carts for us.

Frau von Eckthum laughed, and said she was sure we would like it. Flitz himself smoked in silence. And Edelgard developed a sudden eloquence in regard to natural phenomena such as moons and poppies that would have done credit to a young and sentimental girl. “Think of sitting in the shade of some mighty beech tree,” she said, for instance (she actually clasped her hands), “with the beams of the sinking sun slanting through its branches, and doing one’s needlework.”

And she said other things of the same sort, things that made me, who knew she was going to be thirty next birthday, gaze upon her with a deep surprise.

CHAPTER II

I HAVE decided not to show Edelgard my manuscript again, and my reason is that I may have a freer hand. For the same reason I will not, as we at first proposed, send it round by itself among our relations, but will either accompany it in person or invite our relations to a cozy beer-evening, with a simple little cold something to follow, and read aloud such portions of it as I think fit, omitting of course much that I say about Edelgard and probably also a good deal that I say about everybody else. A reasonable man is not a woman, and does not willingly pander to a love of gossip. Besides, as I have already hinted, the Edelgard who came back from England is by no means the Edelgard who went there. It will wear off, I am confident, in time, and we will return to the status quo ante—(how naturally that came out: it gratifies me to see I still remember)—a status quo full of trust and obedience on the one side and of kind and wise guidance on the other. Surely I have a right to refuse to be driven, except by a silken thread? When I, noticing a tendency on Edelgard’s part to attempt to substitute, if I may so express it, leather, asked her the above question, will it be believed that what she answered was Bosh?

It gave me a great shock to hear her talk like that. Bosh is not a German expression at all. It is purest English. And it amazes me with what rapidity she picked it and similar portions of the language up, adding them in quantities to the knowledge she already possessed of the tongue, a fairly complete knowledge (she having been well educated), but altogether excluding words of that sort. Of course I am aware it was all Jellaby’s fault—but more of him in his proper place; I will not now dwell on later incidents while my narrative is still only at the point where everything was eager anticipation and preparation.

Our caravan had been hired; I had sent, at Frau von Eckthum’s direction, the money to the owner, the price (unfortunately) having to be paid beforehand; and August the first, the very day of my wedding with poor Marie-Luise, was to see us start. Naturally there was much to do and arrange, but it was pleasurable work such as getting a suit of civilian clothes adapted to the uses it would be put to, searching for stockings to match the knickerbockers, and for a hat that would be useful in both wet weather and sunshine.

“It will be all sunshine,” said Frau von Eckthum with her really unusually pretty smile (it includes the sudden appearance of two dimples) when I expressed fears as to the effect of rain on the Panama that I finally bought and which, not being a real one, made me anxious.

We saw her several times because of our need for hints as to luggage, meeting place, etc., and I found her each time more charming. When she was on her feet, too, her dress hid the shoes; and she was really helpful, and was apparently looking forward greatly to showing us the beauties of her sister’s more or less native land.

As soon as my costume was ready I put it on and drove out to see her. The stockings had been a difficulty because I could not bear, accustomed as I am to cotton socks, their woollen feet. This was at last surmounted by cutting off their feet and sewing my ordinary sock feet on to the woollen legs. It answered splendidly, and Edelgard assured me that with care no portion of the sock (which was not of the same colour) would protrude. She herself had sent to Berlin to Wertheim for one of the tailor-made dresses in his catalogue, which turned out to be of really astonishing value for the money, and in which she looked very nice. With a tartan silk blouse and a little Tyrolese hat and a pheasant’s feather stuck in it she was so much transformed that I declared I could not believe it was our silver wedding journey, and I felt exactly as I did twenty-five years before.

“But it is not our silver wedding journey,” she said with some sharpness.

“Dear wife,” I retorted surprised, “you know very well that it is mine, and what is mine is also by law yours, and that therefore without the least admissible logical doubt it is yours.”

She made a sudden gesture with her shoulders that was almost like impatience; but I, knowing what victims the best of women are to incomprehensible moods, went out and bought her a pretty little bag with a leather strap to wear over one shoulder and complete her attire, thus proving to her that a reasonable man is not a child and knows when and how to be indulgent.

Frau von Eckthum, who was going to stay with her sister for a fortnight before they both joined us (the sister, I regretted to hear, was coming too), left in the middle of July. Flitz, at that time incomprehensibly to me, made excuses for not taking part in the caravan tour, but since then light has been thrown on his behaviour: he said, I remember, that he could not leave his pigs.

“Much better not leave his sister,” said Edelgard who, I fancy, was just then a little envious of Frau von Eckthum.

“Dear wife,” I said gently, “we shall be there to take care of her and he knows she is safe in our hands. Besides, we do not want Flitz. He is the last man I can imagine myself ever wanting.”

It was perfectly natural that Edelgard should be a little envious, and I felt it was and did not therefore in any way check her. I need not remind those relatives who will next winter listen to this that the Flitzes of Flitzburg, of whom Frau von Eckthum was one, are a most ancient and still more penniless family. Frau von Eckthum and her gaunt sister (last time she was staying in Prussia both Edelgard and I were struck with her extreme gauntness) each married a wealthy man by two most extraordinary strokes of luck; for what man nowadays will marry a girl who cannot take, if not the lion’s share, at least a very substantial one of the household expenses upon herself? What is the use of a father if he cannot provide his daughter with the money required suitably to support her husband and his children? I myself have never been a father, so that I am qualified to speak with perfect impartiality; that is, strictly, I was one twice, but only for so few minutes each time that they can hardly be said to count. The two von Flitz girls married so young and so well, and have been, without in any way really deserving it, so snugly wrapped in comfort ever since (Frau von Eckthum actually losing her husband two years after marriage and coming into everything) that naturally Edelgard cannot be expected to like it. Edelgard had a portion herself of six thousand marks a year besides an unusual quantity of house linen, which enabled her at last—she was twenty-four when I married her—to find a good husband; and she cannot understand by what wiles the two sisters, without a penny or a table cloth, secured theirs at eighteen. She does not see that they are—“were” is the better word in the case of the gaunt sister—attractive; but then the type is so completely opposed to her own that she would not be likely to. Certainly I agree that a married woman verging, as the sister must be, on thirty should settle down to a smooth head and at least the beginnings of a suitable embonpoint. We do not want wives like lieutenants in a cavalry regiment; and Edelgard is not altogether wrong when she says that both Frau von Eckthum and her sister make her think of those lean and elegant young men. Your lean woman with her restlessness of limb and brain is far indeed removed from the soft amplitudes and slow movements of her who is the ideal wife of every German better-class bosom. Privately, however, I feel I can at least understand that there may have been something to be said at the time for the Englishman’s conduct, and I more than understand that of the deceased Eckthum. No one can deny that his widow is undoubtedly—well, well; let me return to the narrative.

We had naturally told everybody we met what we were going to do, and it was intensely amusing to see the astonishment created. Bad health for the rest of our days was the smallest of the evils predicted. Also our digestions were much commiserated. “Oh,” said I with jaunty recklessness at that, “we shall live on boiled hedgehogs, preceded by mice soup,”—for I had studied the article Gipsies in our Encyclopædia, and discovered that they often eat the above fare.

The faces of our friends when I happened to be in this jocose vein were a study. “God in heaven,” they cried, “what will become of your poor wife?”

But a sense of humour carries a man through anything, and I did not allow myself to be daunted. Indeed it was not likely, I reminded myself sometimes when inclined to be thoughtful at night, that Frau von Eckthum, who so obviously was delicately nurtured, would consent to eat hedgehogs or risk years in which all her attractiveness would evaporate on a sofa of sickness.

“Oh, but Frau von Eckthum——!” was the invariable reply, accompanied by a shrug when I reassured the ladies of our circle by pointing this out.

I am aware Frau von Eckthum is unpopular in Storchwerder. Perhaps it is because the art of conversation is considerably developed there, and she will not talk. I know she will not go to its balls, refuses its dinners, and turns her back on its coffees. I know she is with difficulty induced to sit on its philanthropic boards, and when she finally has been induced to sit on them does not do so after all but stays at home. I know she is different from the type of woman prevailing in our town, the plain, flat-haired, tightly buttoned up, God-fearing wife and mother, who looks up to her husband and after her children, and is extremely intelligent in the kitchen and not at all intelligent out of it. I know that this is the type that has made our great nation what it is, hoisting it up on ample shoulders to the first place in the world, and I know that we would have to request heaven to help us if we ever changed it. But—she is an attractive lady.

Truly it is an excellent thing to be able to put down one’s opinions on paper as they occur to one without risk of irritating interruption—I hope my hearers will not interrupt at the reading aloud—and now that I have at last begun to write a book—for years I have intended doing so—I see clearly the superiority of writing over speaking. It is the same kind of superiority that the pulpit enjoys over the (very properly) muzzled pews. When, during my stay on British soil, I said anything, however short, of the nature of the above remarks about our German wives and mothers, it was most annoying the way I was interrupted and the sort of questions that were instantly put me by, chiefly, the gaunt sister. But of that more in its place. I am still at the point where she had not yet loomed on my horizon, and all was pleasurable anticipation.

We left our home on August 1st, punctually as we had arranged, after some very hard-worked days at the end during which the furniture was beaten and strewn with napthalin (against moths), curtains, etc., taken down and piled neatly in heaps, pictures covered up in newspapers, and groceries carefully weighed and locked up. I spent these days at the Club, for my leave had begun on the 25th of July and there was nothing for me to do. And I must say, though the discomfort in our flat was intense, when I returned to it in the evening in order to go to bed I was never anything but patient with the unappetisingly heated and disheveled Edelgard. And she noticed it and was grateful. It would be hard to say what would make her grateful now. These last bad days, however, came to their natural end, and the morning of the first arrived and by ten we had taken leave, with many last injunctions, of Clothilde who showed an amount of concern at our departure that gratified us, and were on the station platform with Hermann standing respectfully behind us carrying our hand luggage in both his gloved hands, and with what he could not carry piled about his feet, while I could see by the expression on their faces that the few strangers present recognized we were people of good family or, as England would say, of the Upper Ten. We had no luggage for registration because of the new law by which every kilo has to be paid for, but we each had a well-filled, substantial hold-all and a leather portmanteau, and into these we had succeeded in packing most of the things Frau von Eckthum had from time to time suggested we might want. Edelgard is a good packer, and got far more in than I should have thought possible, and what was left over was stowed away in different bags and baskets. Also we took a plentiful supply of vaseline and bandages. “For,” as I remarked to Edelgard when she giddily did not want to, quoting the most modern (though rightly disapproved of in Storchwerder) of English writers, “you never can possibly tell,”—besides a good sized ox-tongue, smoked specially for us by our Storchwerder butcher and which was later on to be concealed in our caravan for private use in case of need at night.

The train did not start till 10:45, but we wanted to be early in order to see who would come to see us off; and it was a very good thing we were in such good time, for hardly a quarter of an hour had elapsed before, to my dismay, I recollected that I had left my Panama at home. It was Edelgard’s fault, who had persuaded me to wear a cap for the journey and carry my Panama in my hand, and I had put it down on some table and in the heat of departure forgotten it. I was deeply annoyed, for the whole point of the type of costume I had chosen would be missed without just that kind of hat, and, at my sudden exclamation and subsequent explanation of my exclamation, Edelgard showed that she felt her position by becoming exceedingly red.

There was nothing for it but to leave her there and rush off in a droschke to our deserted flat. Hurrying up the stairs two steps at a time and letting myself in with my latch-key I immediately found the Panama on the head of one of the privates in my own battalion, who was lolling in my chair at the breakfast-table I had so lately left being plied with our food by the miserable Clothilde, she sitting on Edelgard’s chair and most shamelessly imitating her mistress’s manner when she is affectionately persuading me to eat a little bit more.

The wretched soldier, I presume, was endeavouring to imitate me, for he called her a dear little hare, an endearment I sometimes apply to my wife, on Clothilde’s addressing him as Edelgard sometimes does (or rather did) me in her softer moments as sweet snail. The man’s imitation of me was a very poor affair, but Clothilde hit my wife off astoundingly well, and both creatures were so riotously mirthful that they neither heard nor saw me as I stood struck dumb in the door. The clock on the wall, however, chiming the half-hour recalled me to the necessity for instant action, and rushing forward I snatched the Panama off the amazed man’s head, hurled a furious dismissal at Clothilde, and was out of the house and in the droschke before they could so much as pray for mercy. Immediately on arriving at the station I took Hermann aside and gave him instructions about the removal within an hour of Clothilde, and then, swallowing my agitation with a gulp of the man of the world, I was able to chat courteously and amiably with friends who had collected to see us off, and even to make little jokes as though nothing whatever had happened. Of course directly the last smile had died away at the carriage window and the last handkerchief had been fluttered and the last promise to send many picture postcards had been made, and our friends had become mere black and shapeless masses without bodies, parts or passions on the grey of the receding platform, I recounted the affair to Edelgard, and she was so much upset that she actually wanted to get out at the next station and give up our holiday and go back and look after her house.

Strangely enough, what upset her more than the soldier’s being feasted at our expense and more than his wearing my new hat while he feasted, was the fact that I had dismissed Clothilde.

“Where and when am I to get another?” was her question, repeated with a plaintiveness that was at length wearisome. “And what will become of all our things now during our absence?”

“Would you have had me not dismiss her instantly, then?” I cried at last, goaded by this persistence. “Is every shamelessness to be endured? Why, if the woman were a man and of my own station, honour would demand that I should fight a duel with her.”

“But you cannot fight a duel with a cook,” said Edelgard stupidly.

“Did I not expressly say that I could not?” I retorted; and having with this reached the point where patience becomes a weakness I was obliged to put it aside and explain to her with vigour that I am not only not a fool but decline to be talked to as if I were. And when I had done, she having given no further rise to discussion, we were both silent for the rest of the way to Berlin.

This was not a bright beginning to my holiday, and I thought with some gloom of the difference between it and the start twenty-five years before with my poor Marie-Luise. There was no Clothilde then, and no Panama hat (for they were not yet the fashion), and all was peace. Unwilling, however, to send Edelgard, as the English say, any longer to Coventry—we are both good English scholars as my hearers know—when we got into the droschke in Berlin that was to take us across to the Potsdamer Bahnhof (from which station we departed for London via Flushing) I took her hand, and turning (not without effort) an unclouded face to her, said some little things which enabled her to become aware that I was willing once again to overlook and forgive.

Now I do not propose to describe the journey to London. So many of our friends know people who have done it that it is not necessary for me to dwell upon it further than to say that, being all new to us, it was not without its charm—at least, up to the moment when it became so late that there were no more meals taking place in the restaurant-car and no more attractive trays being held up to our windows at the stations on the way. About what happened later in the night I would not willingly speak: suffice it to say that I had not before realized the immense and apparently endless distance of England from the good dry land of the Continent. Edelgard, indeed, behaved the whole way up to London as if she had not yet got to England at all; and I was forced at last to comment very seriously on her conduct, for it looked as much like wilfulness as any conduct I can remember to have witnessed.

We reached London at the uncomfortable hour of 8 A.M., or thereabouts, chilled, unwell, and disordered. Although it was only the second of August a damp autumn draught pervaded the station. Shivering, we went into the sort of sheep-pen in which our luggage was searched for dutiable articles, Edelgard most inconsiderately leaving me to bear the entire burden of opening and shutting our things, while she huddled into a corner and assumed (very conveniently) the air of a sufferer. I had to speak to her quite sharply once when I could not fit the key of her portmanteau into its lock and remind her that I am not a lady’s maid, but even this did not rouse her, and she continued to huddle apathetically. It is absurd for a wife to collapse at the very moment when she ought to be most helpful; the whole theory of the helpmeet is shattered by such behaviour. And what can I possibly know about Customs? She looked on quite unmoved while I struggled to replace the disturbed contents of our bags, and my glances, in turn appealing and indignant, did not make her even raise her head. There were too many strangers between us for me to be able to do more than glance, so

Edelgard most inconsiderately leaving me to bear the entire burden of opening and shutting our things

reserving what I had to say for a more private moment I got the bags shut as well as I could, directed the most stupid porter (who was also apparently deaf, for each time I said anything to him he answered perfectly irrelevantly with the first letter of the alphabet) I have ever met to conduct me and the luggage to the refreshment room, and far too greatly displeased with Edelgard to take any further notice of her, walked on after the man leaving her to follow or not as she chose.

I think people must have detected as I strode along that I was a Prussian officer, for so many looked at me with interest. I wished I had had my uniform and spurs on, so that for once the non-martial island could have seen what the real thing is like. It was strange to me to be in a crowd of nothing but civilians. In spite of the early hour every arriving train disgorged myriads of them of both sexes. Not the flash of a button was to be seen; not the clink of a sabre to be heard; but, will it be believed? at least every third person arriving carried a bunch of flowers, often wrapped in tissue paper and always as carefully as though it had been a specially good belegtes Brödchen. That seemed to me very characteristic of the effeminate and non-military nation. In Prussia useless persons like old women sometimes transport bunches of flowers from one point to another—but that a man should be seen doing so, a man going evidently to his office, with his bag of business papers and his grave face, is a sight I never expected to see. The softness of this conduct greatly struck me. I could understand a packet of some good thing to eat between meals being brought, some tit-bit from the home kitchen—but a bunch of flowers! Well, well; let them go on in their effeminacy. It is what has always preceded a fall, and the fat little land will be a luscious morsel some day for muscular continental (and almost certainly German) jaws.

We had arranged to go straight that very day to the place in Kent where the caravans and Frau von Eckthum and her sister were waiting for us, leaving the sights of London for the end of our holiday, by which time our already extremely good though slow and slightly literary English (by which I mean that we talked more as the language is written than other people do, and that we were singularly pure in the matter of slang) would have developed into an up-to-date agility; and there being about an hour and a half’s time before the train for Wrotham started—which it conveniently did from the same station we arrived at—our idea was to have breakfast first and then, perhaps, to wash. This we accordingly did in the station restaurant, and made the astonishing acquaintance of British coffee and butter. Why, such stuff would not be tolerated for a moment in the poorest wayside inn in Germany, and I told the waiter so very plainly; but he only stared with an extremely stupid face, and when I had done speaking said “Eh?”

It was what the porter had said each time I addressed him, and I had already, therefore, not then knowing what it was or how it was spelt, had about as much of it as I could stand.

“Sir,” said I, endeavoring to annihilate the man with that most powerful engine of destruction, a witticism, “what has the first letter of the alphabet to do with everything I say?”

“Eh?” said he.

“Suppose, sir,” said I, “I were to confine my remarks to you to a strictly logical sequence, and when you say A merely reply B—do you imagine we should ever come to a satisfactory understanding?”

“Eh?” said he.

“Yet, sir,” I continued, becoming angry, for this was deliberate impertinence, “it is certain that one letter of the alphabet is every bit as good as another for conversational purposes.”

“Eh?” said he; and began to cast glances about him for help.

“This,” said I to Edelgard, “is typical. It is what you must expect in England.”

The head waiter here caught one of the man’s glances and hurried up.

“This gentleman,” said I, addressing the head waiter and pointing to his colleague, “is both impertinent and a fool.”

“Yes, sir. German, sir,” said the head waiter, flicking away a crumb.

Well, I gave neither of them a tip. The German was not given one for not at once explaining his inability to get away from alphabetical repartee and so shamefully hiding the nationality he ought to have openly rejoiced in, and the head waiter because of the following conversation:

“Can’t get ’em to talk their own tongue, sir,” said he, when I indignantly inquired why he had not. “None of ’em will, sir. Hear ’em putting German gentry who don’t know English to the greatest inconvenience. ‘Eh?’ this one’ll say—it’s what he picks up his first week, sir. ‘A thousand damns,’ say the German gentry, or something to that effect. ‘All right,’ says the waiter—that’s what he picks up his second week—and makes it worse. Then the German gentry gets really put out, and I see ’em almost foamin’ at the mouth. Impatient set of people, sir——”

“I conclude,” said I, interrupting him with a frown, “that the object of these poor exiled fellows is to learn the language as rapidly as possible and get back to their own country.”

“Or else they’re ashamed of theirs, sir,” said he, scribbling down the bill. “Rolls, sir? Eight, sir? Thank you, sir——”

“Ashamed?”

“Quite right, sir. Nasty cursin’ language. Not fit for a young man to get into the habit of. Most of the words got a swear about ’em somewhere, sir.”

“Perhaps you are not aware,” said I icily, “that at this very moment you are speaking to a German gentleman.”

“Sorry, sir. Didn’t notice it. No offence meant. Two coffees, four boiled eggs, eight—you did say eight rolls, sir? Compliment really, you know, sir.”

“Compliment!” I exclaimed, as he whisked away with the money to the paying desk; and when he came back I pocketed, with elaborate deliberation, every particle of change.

“That is how,” said I to Edelgard while he watched me, “one should treat these fellows.”

To which she, restored by the hot coffee to speaking point, replied (rather stupidly I thought),

“Is it?”

CHAPTER III

SHE became, however, more normal as the morning wore on, and by about eleven o’clock was taking an intelligent interest in hop-kilns.

These objects, recurring at frequent intervals as one travels through the county of Kent, are striking and picturesque additions to the landscape, and as our guide-book described them very fully I was able to talk a good deal about them. Kent pleased me very well. It looked as if there were money in it. Many thriving villages, many comfortable farmhouses, and many hoary churches peeping slyly at us through surrounding groups of timber so ancient that its not yet having been cut down and sold is in itself a testimony to the prevailing prosperity. It did not need much imagination to picture the comfortable clergyman lurking in the recesses of his snug parsonage and rubbing his well-nourished hands at life. Well, let him rub. Some day perhaps—and who knows how soon?—we shall have a decent Lutheran pastor in his black gown preaching the amended faith in every one of those churches.

Shortly, then, Kent is obviously flowing with milk and honey and well-to-do inhabitants; and when on referring to our guide-book I found it described as the Garden of England I was not in the least surprised, and neither was Edelgard. In this county, as we knew, part at any rate of our gipsying was to take place, for the caravans were stationed at a village about three miles from Wrotham, and we were very well satisfied that we were going to examine it more closely, because though no one could call the scenery majestic it yet looked full of promise of a comfortable nature. I observed for instance that the roads seemed firm and good, which was clearly important; also that the villages were so plentiful that there would be no fear of our ever getting beyond the reach of provisions. Unfortunately, the weather was not true August weather, which I take it is properly described by the word bland. This is not bland. The remains of the violent wind that had blown us across from Flushing still hurried hither and thither, and gleams of sunshine only too frequently gave place to heavy squalls of rain and hail. It was more like a blustering October day than one in what is supposed to be the very height and ripeness of summer, and we could only both hope, as the carriage windows banged and rattled, that our caravan would be heavy enough to withstand the temptation to go on by itself during the night, urged on from behind by the relentless forces of nature. Still, each time the sun got the better of the inky clouds and the Garden of England laughed at us from out of its bravery of graceful hop-fields and ripening corn, we could not resist a feeling of holiday hopefulness. Edelgard’s spirits rose with every mile, and I, having readily forgiven her on her asking me to and acknowledging she had been selfish, was quite like a boy; and when we got out of the train at Wrotham beneath a blue sky and a hot sun with the hail-clouds retreating over the hills and found we would have to pack ourselves and our many packages into a fly so small that, as I jocularly remarked in English, it was not a fly at all but an insect, Edelgard was so much entertained that for several minutes she was perfectly convulsed with laughter.

By means of the address neatly written in Latin characters on an envelope, we had no difficulty in getting the driver to start off as though he knew where he was going, but after we had been on the way for about half an hour he grew restless, and began to twist round on his box and ask me unintelligible questions. I suppose he talked and understood only patois, for I could not in the least make out what he meant, and when I requested him to be more clear I could see by his foolish face that he was constitutionally unable to be it. A second exhibition of the addressed envelope, however, soothed him for a time, and we continued to advance up and down chalky roads, over the hedges on each side of which leapt the wind and tried to blow our hats off. The sun was in our eyes, the dust was in our eyes, and the wind was in our faces. Wrotham, when we looked behind, had disappeared. In front was a chalky desolation. We could see nothing approaching a village, yet Panthers, the village we were bound for, was only three miles from the station, and not, observe, three full-blooded German miles, but the dwindled and anæmic English kind that are typical, as so much else is, of the soul and temper of the nation. Therefore we began to be uneasy, and to wonder whether the man were trustworthy. It occurred to me that the chalk pits we constantly met would not be bad places to take us into and rob us, and I certainly could not speak English quickly enough to meet a situation demanding rapid dialogue, nor are there any directions in my German-English Conversational Guide as to what you are to say when you are being murdered.

Still jocose, but as my hearers will notice, jocose with a tinge of grimness, I imparted these two linguistic facts to Edelgard, who shuddered and suggested renewed applications of the addressed envelope to the driver. “Also it is past dinner time,” she added anxiously. “I know because mein Magen knurrt.”

By means of repeated calls and my umbrella I drew the driver’s attention to us and informed him that I would stand no further nonsense. I told him this with great distinctness and the deliberation forced upon me by want of practice. He pulled up to hear me out, and then, merely grinning, drove on. “The youngest Storchwerder droschke driver,” I cried indignantly to Edelgard, “would die of shame on his box if he did not know every village, nay, every house within three miles of it with the same exactitude with which he knows the inside of his own pocket.”

Then I called up to the man once more, and recollecting that nothing clears our Hermann’s brain at home quicker than to address him as Esel I said, “Ask, ass.”

He looked down over his shoulder at me with an expression of great surprise.

“What?” said he.

“What?” said I, confounded by this obtuseness. “What? The way, of course.”

He pulled up once more and turned right round on his box.

“Look here——” he said, and paused.

“Look where?” said I, very naturally supposing he had something to show me.

“Who are you talkin’ to?” said he.

The question on the face of it was so foolish that a qualm gripped my heart lest we had to do with a madman. Edelgard felt the same, for she drew closer to me.

Luckily at that moment I saw a passer-by some way down the road, and springing out of the fly hastened to meet him in spite of Edelgard’s demand that I should not leave her alone. On reaching him I took off my hat and courteously asked him to direct us to Panthers, at the same time expressing my belief that the flyman was not normal. He listened with the earnest and strained attention English people gave to my utterances, an attention caused, I believe, by the slightly unpractised pronunciation combined with the number and variety of words at my command, and then going up (quite fearlessly) to the flyman he pointed in the direction entirely opposed to the one we were following and bade him go there.

“I won’t take him nowhere,” said the flyman with strange passion; “he calls me a ass.”

“It is not your fault,” said I (very handsomely, I thought). “You are what you were made. You cannot help yourself.”

“I won’t take him nowhere,” repeated the flyman, with, if anything, increased passion.

The passer-by looked from one to another with a faint smile.

“The expression,” said he to the flyman, “is, you see, merely a term of recognition in the gentleman’s country. You can’t reasonably object to that, you know. Drive on like a sensible man, and get your fare.”

And lifting his hat to Edelgard he continued his passing by.

Well, we did finally arrive at the appointed place—indeed, my hearers next winter will know all the time that we must have, or why should I be reading this aloud?—after being forced by the flyman to walk the last twenty minutes up a hill which, he declared, his horse would not otherwise be able to ascend. The sun shone its hottest while we slowly surmounted this last obstacle—a hard one to encounter when it is long past dinner-time. I am aware that by English clocks it was not past it, but what was that to me? My watch showed that in Storchwerder, the place our inner natures were used to, it was half-past two, a good hour beyond the time at which they are accustomed daily to be replenished, and no arbitrary theory, anyhow no perilously near approach to one, will convince a man against the evidence of his senses that he is not hungry because a foreign clock says it is not dinner-time when it is.

Panthers, we found on reaching the top of the hill and pausing to regain our composure, is but a house here and a house there scattered over a

The sun shone its hottest while we slowly surmounted this last obstacle

bleak, ungenial landscape. It seemed an odd, high up district to use as a terminus for caravans, and I looked down the steep, narrow lane we had just ascended and wondered how a caravan would get up it. Afterward I found that they never do get up it, but arrive home from the exactly opposite direction along a fair road which was the one any but an imbecile driver would have brought us. We reached our destination by, so to speak, its back door; and we were still standing on the top of the hill doing what is known as getting one’s wind, for I am not what would be called an ill-covered man but rather, as I jestingly tell Edelgard, a walking compliment to her good cooking, and she herself was always of a substantial build, not exaggeratedly but agreeably so—we were standing, I say, struggling for breath when some one came out quickly from a neighbouring gate and stopped with a smile of greeting upon seeing us.

It was the gaunt sister.

We were greatly pleased. Here we were, then, safely arrived, and joined to at least a portion of our party. Enthusiastically we grasped both her hands and shook them. She laughed as she returned our greetings, and I was so much pleased to find some one I knew that though Edelgard commented afterward somewhat severely on her dress because it was so short that it nowhere touched the ground, I noticed nothing except that it seemed to be extremely neat, and as for not touching the ground Edelgard’s skirt was followed wherever she went by a cloud of chalky dust which was most unpleasant.

Now why were we so glad to see this lady again? Why, indeed, are people ever glad to see each other again? I mean people who when they last saw each other did not like each other. Given a sufficient lapse of time, and I have observed that even those who parted in an atmosphere thick with sulphur of implied cursings will smile and genially inquire how the other does. I have observed this, I say, but I cannot explain it. There had, it is true, never been any sulphur about our limited intercourse with the lady on the few occasions on which proper feeling prevailed enough to induce her to visit her flesh and blood in Prussia—our attitude toward her had simply been one of well-bred chill, of chill because no thinking German can, to start with, be anything but prejudiced against a person who commits the unpatriotism—not to call it by a harsher name—of selling her inestimable German birthright for the mess of an English marriage. Also she was personally not what Storchwerder could like, for she was entirely wanting in the graces and undulations of form which are the least one has a right to expect of a being professing to be a woman. Also she had a way of talking which disconcerted Storchwerder, and nobody likes being disconcerted. Our reasons for joining issue with her in the matter of caravans were first, that we could not help it, only having discovered she was coming when it was too late; and secondly, that it was a cheap and convenient way of seeing a new country. She with her intimate knowledge of English was to be, we privately told each other, our unpaid courier—I remember Edelgard’s amusement when the consolatory cleverness of this way of looking at it first struck her.

But I am still at a loss to explain how it was that when she unexpectedly appeared at the top of the hill at Panthers we both rushed at her with an effusiveness that could hardly have been exceeded if it had been Edelgard’s grandmother Podhaben who had suddenly stood before us, an old lady of ninety-two of whom we are both extremely fond, and who, as is well known, is going to leave my wife her money when she (which I trust sincerely she will not do for a long time yet) dies. I cannot explain it, I say, but there it is. Rush we did, and effusive we were, and it was reserved for a quieter moment to remember with some natural discomposure that we had showed far more enthusiasm than she had. Not that she was not pleasant, but there is a gap between pleasantness and enthusiasm, and to be the one of two persons who is most pleased is to put yourself in the position of the inferior, of the suppliant, of him who hopes, or is eager to ingratiate himself. Will it be believed that when later on I said something to this effect about some other matter in general conversation, the gaunt sister immediately cried, “Oh, but that’s not generous.”

“What is not generous?” I asked surprised, for it was the first day of the tour and I was not then as much used as I subsequently became to her instant criticism of all I said.

“That way of thinking,” said she.

Edelgard immediately bristled—(alas, what would make her bristle now?)

“Otto is the most generous of men,” she said. “Every year on Sylvester evening he allows me to invite six orphans to look at the remains of our Christmas tree and be given, before they go away, doughnuts and grog.”

“What! Grog for orphans?” cried the gaunt sister, neither silenced nor impressed; and there ensued a warm discussion on, as she put it, (a) the effect of grog on orphans, (b) the effect of grog on doughnuts, (c) the effect of grog on combined orphans and doughnuts.

But I not only anticipate, I digress.

Inside the gate through which this lady had emerged stood the caravans and her gentle sister. I was so much pleased at seeing Frau von Eckthum again that at first I did not notice our future homes. She was looking remarkably well and was in good spirits, and, though dressed in the same way as her sister, by adding to the attire all those graces so peculiarly her own the effect she produced was totally different. At least, I thought so. Edelgard said she saw nothing to choose between them.

After the first greetings she half turned to the row of caravans, and with a little motion of the hand and a pretty smile of proprietary pride said, “There they are.”

There, indeed, they were.

There were three; all alike, sober brown vehicles, easily distinguishable, as I was pleased to notice, from common gipsy carts. Clean curtains fluttered at the windows, the metal portions were bright, and the names painted prettily on them were the Elsa, the Ilsa, and the Ailsa. It was an impressive moment, the moment of our first setting eyes upon them. Under those frail roofs were we for the next four weeks to be happy, as Edelgard said, and healthy and wise—“Or,” I amended shrewdly on hearing her say this, “vice versa.”

Frau von Eckthum, however, preferred Edelgard’s prophecy, and gave her an appreciative look—my hearers will remember, I am sure, how agreeably her dark eyelashes contrast with the fairness of her hair. The gaunt sister laughed, and suggested that we should paint out the names already on the caravans and substitute in large letters Happy, Healthy, and Wise, but not considering this particularly amusing I did not take any trouble to smile.

Three large horses that were to draw them and us stood peacefully side by side in a shed being fed with oats by a weather-beaten person the gaunt sister introduced as old James. This old person, a most untidy, dusty-looking creature, touched his cap, which is the inadequate English way of showing respect to superiors—as inadequate at its end of the scale as the British army is at the other—and shuffled off to fetch in our luggage, and the gaunt sister suggesting that we should climb up and see the interior of our new home with some difficulty we did so, there being a small ladder to help us which, as a fact, did not help us either then or later, no means being discovered from beginning to end of the tour by which it could be fixed firmly at a convenient angle.

I think I could have climbed up better if Frau von Eckthum had not been looking on; besides, at that moment I was less desirous of inspecting the caravans than I was of learning when, where, and how we were going to have our delayed dinner. Edelgard, however, behaved like a girl of sixteen once she had succeeded in reaching the inside of the Elsa, and most inconsiderately kept me lingering there too while she examined every corner and cried with tiresome iteration that it was wundervoll, herrlich, and putzig.

“I knew you’d like it,” said Frau von Eckthum from below, amused apparently by this kittenish conduct.

“Like it?” called back Edelgard. “But it is delicious—so clean, so neat, so miniature.”

“May I ask where we dine?” I inquired, endeavouring to free the skirts of my new mackintosh from the door, which had swung to (the caravan not standing perfectly level) and jammed them tightly. I did not need to raise my voice, for in a caravan even with its door and windows shut people outside can hear what you say just as distinctly as people inside, unless you take the extreme measure of putting something thick over your head and whispering. (Be it understood I am alluding to a caravan at rest: when in motion you may shout your secrets, for the noise of crockery leaping and breaking in what we learned—with difficulty—to allude to as the pantry will effectually drown them.)

The two ladies took no heed of my question, but coming up after us—they never could have got in had they been less spare—filled the van to overflowing while they explained the various arrangements by which our miseries on the road were to be mitigated. It was chiefly the gaunt sister who talked, she being very nimble of tongue, but I must say that on this occasion Frau von Eckthum did not confine herself to the attitude I so much admired in her, the ideal feminine one of smiling and keeping quiet. I, meanwhile, tried to make myself as small as possible, which is what persons in caravans try to do all the time. I sat on a shiny yellow wooden box that ran down one side of our “room” with holes in its lid and a flap at the end by means of which it could, if needed, be lengthened and turned into a bed for a third sufferer. (On reading this aloud I shall probably substitute traveller for sufferer, and some milder word such as discomfort for the word miseries in the first sentence of the paragraph.) Inside the box was a mattress, also extra sheets, towels, etc., so that, the gaunt sister said there was nothing to prevent our having house-parties for week-ends. As I do not like such remarks even in jest I took care to show by my expression that I did not, but Edelgard, to my surprise, who used always to be the first to scent the vicinity of thin ice, laughed heartily as she continued her frantically pleased examination of the van’s contents.

It is not to be expected of any man that he shall sit in a cramped position on a yellow box at an hour long past his dinner time and take an interest in puerilities. To Edelgard it seemed to be a kind of a doll’s house, and she, entirely forgetting the fact of which I so often reminded her that she will be thirty next birthday, behaved in much the same way as a child who has just been presented with this expensive form of toy by some foolish and spendthrift relation. Frau von Eckthum, too, appeared to me to be less intelligent than I was accustomed to suppose her. She smiled at Edelgard’s delight as though it pleased her, chatting in a way I hardly recognized as she drew my wife’s attention to the objects she had not had time to notice. Edelgard’s animation amazed me. She questioned and investigated and admired without once noticing that as I sat on the lid of the wooden box I was obviously filled with sober thoughts. Why, she was so much infatuated that she actually demanded at intervals that I too should join in this exhibition of childishness; and it was not until I said very pointedly that I, at least, was not a little girl, that she was recalled to a proper sense of her behaviour.

“Poor Otto is hungry,” she said, pausing suddenly in her wild career round the caravan and glancing at my face.

“Is he? Then he must be fed,” said the gaunt sister, as carelessly and with as little real interest as if there were no particular hurry. “Look—aren’t these too sweet?—each on its own little hook—six of them, and their saucers in a row underneath.”

And so it would have gone on indefinitely if an extremely pretty, nice, kind little lady had not put her head in at the door and asked with a smile that fell like oil on the troubled water of my brain whether we were not dying for something to eat.

Never did the British absence of ceremony and introductions and preliminary phrases seem to me excellent before. I sprang up, and immediately knocked my elbow so hard against a brass bracket holding a candle and hanging on a hook in the wall that I was unable altogether to suppress an exclamation of pain. Remembering, however, what is due to society I very skilfully converted it into a rather precipitate and agonized answer to the little lady’s question, and she, with a charming hospitality, pressing me to come into her adjoining garden and have some food, I accepted with alacrity, only regretting that I was unable, from the circumstance of her going first, to help her down the ladder. (As a matter of fact she had in the end to help me, because the door slammed behind me and again imprisoned the skirts of my mackintosh.)

Edelgard, absorbed in delighted contemplation of a corner beneath the so-called pantry full of brooms and dusters also hanging in rows on hooks, only shook her head when I inquired if she would not come too; so leaving her to her ecstasies I went off with my new protector, who asked me why I wore a mackintosh when there was not a cloud in the sky. I avoided giving a direct answer by retorting playfully (though wholly politely), “Why not?”—and indeed my reasons, connected with creases and other ruin attendant on confinement in a hold-all, were of too domestic and private a nature to be explained to a stranger so charming. But my counter-question luckily amused her, and she laughed as she opened a small gate in the wall and led me into her garden.

Here I was entertained with the greatest hospitality by herself and her husband. The fleet of caravans which yearly pervades that part of England is stationed when not in action on their premises. Hence departs the joyful caravaner, accompanied by kind wishes; hither he returns sobered, and is received with balm and bandages—at least, I am sure he would find them and every other kind form of solace in the little garden on the hill. I spent a very pleasant and reviving half-hour in a sheltered corner of it, enjoying my al fresco meal and acquiring much information. To my question as to whether my entertainers were to be of our party they replied, to my disappointment, that they were not. Their functions were restricted to this seeing that we started happy, and being prompt and helpful when we came back. From them I learned that our party was to consist, besides ourselves and Frau von Eckthum and that sister whom I have hitherto distinguished by the adjective gaunt, putting off the necessity as long as possible of alluding to her by name, she having, as my hearers perhaps remember, married a person with the unpronounceable one if you see it written and the unspellable one if you hear it said of Menzies-Legh—the party was to consist, I say, besides these four, of Menzies-Legh’s niece and one of her friends; of Menzies-Legh himself; and of two young men about whom no precise information was obtainable.

“But how? But where?” said I, remembering the limited accommodations of the three caravans.

My host reassured me by explaining that the two young men would inhabit a tent by night which, by day, would be carried in one of the caravans.

“In which one?” I asked anxiously.