Cape Cod

Henry David Thoreau

Cape Cod

by Henry David Thoreau

Author of “A Week on the Concord,” “Walden,”

“Excursions,” “The Maine Woods,” etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY

CLIFTON JOHNSON

NEW YORK

THOMAS Y. CROWELL & CO.

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1908

By THOMAS Y. CROWELL & CO.

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U.S.A.

Contents

| INTRODUCTION |

| I. The Shipwreck |

| II. Stage-coach Views |

| III. The Plains Of Nauset |

| IV. The Beach |

| V. The Wellfleet Oysterman |

| VI. The Beach Again |

| VII. Across the Cape |

| VIII. The Highland Light |

| IX. The Sea and the Desert |

| X. Provincetown |

ILLUSTRATIONS

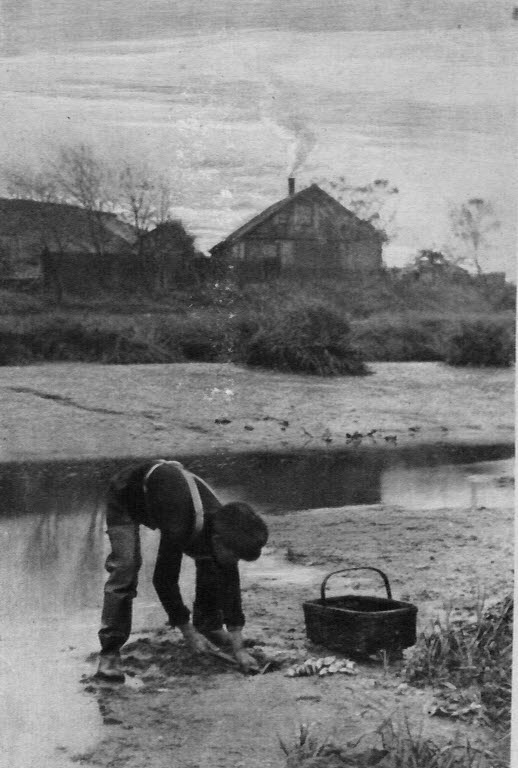

| The Clam-Digger (Photogravure) |

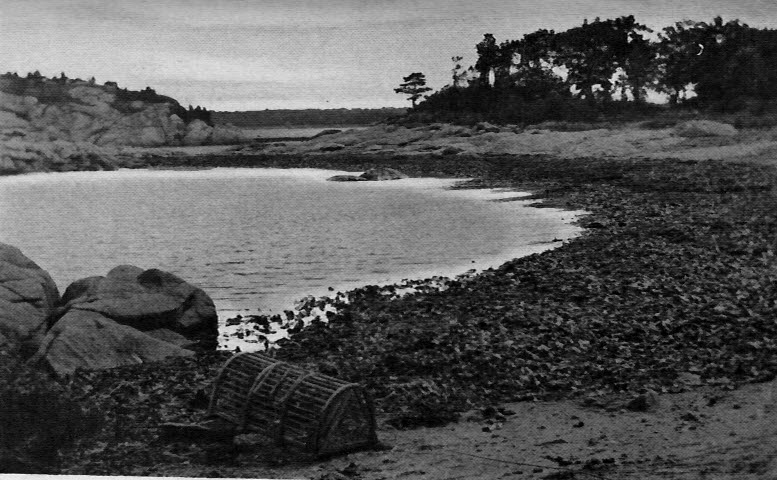

| Cohasset—The little cove at Whitehead promontory |

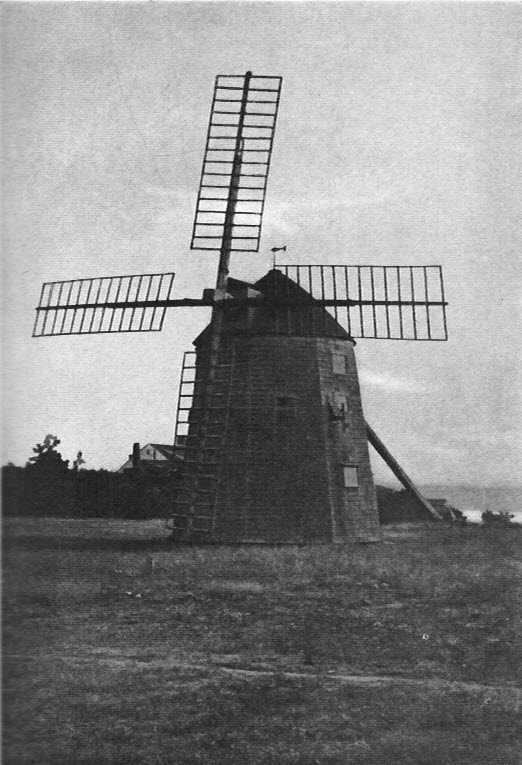

| An old windmill |

| A street in Sandwich |

| The old Higgins tavern at Orleans |

| A Nauset lane |

| Nauset Bay |

| A scarecrow |

| Millennium Grove camp-meeting grounds |

| A Cape Cod citizen |

| Wreckage under the sand-bluff |

| Herring River at Wellfleet |

| A characteristic gable with many windows |

| A Wellfleet oysterman |

| Wellfleet |

| Hunting for a leak |

| Truro—Starting on a voyage |

| Unloading the day’s catch |

| A Truro footpath |

| Truro meeting-house on the hill |

| A herd of cows |

| Pond Village |

| Dragging a dory up on the beach |

| An old wrecker at home |

| The Highland Light |

| Towing along shore |

| A cranberry meadow |

| The sand dunes drifting in upon the trees |

| The white breakers on the Atlantic side |

| In Provincetown harbor |

| Provincetown—A bit of the village from the wharf |

| The day of rest |

| A Provincetown fishing-vessel |

INTRODUCTION

Of the group of notables who in the middle of the last century made the little Massachusetts town of Concord their home, and who thus conferred on it a literary fame both unique and enduring, Thoreau is the only one who was Concord born. His neighbor, Emerson, had sought the place in mature life for rural retirement, and after it became his chosen retreat, Hawthorne, Alcott, and the others followed; but Thoreau, the most peculiar genius of them all, was native to the soil.

In 1837, at the age of twenty, he graduated from Harvard, and for three years taught school in his home town. Then he applied himself to the business in which his father was engaged,—the manufacture of lead pencils. He believed he could make a better pencil than any at that time in use; but when he succeeded and his friends congratulated him that he had now opened his way to fortune he responded that he would never make another pencil. “Why should I?” said he. “I would not do again what I have done once.”

So he turned his attention to miscellaneous studies and to nature. When he wanted money he earned it by some piece of manual labor agreeable to him, as building a boat or a fence, planting, or surveying. He never married, very rarely went to church, did not vote, refused to pay a tax to the State, ate no flesh, drank no wine, used no tobacco; and for a long time he was simply an oddity in the estimation of his fellow-townsmen. But when they at length came to understand him better they recognized his genuineness and sincerity and his originality, and they revered and admired him. He was entirely independent of the conventional, and his courage to live as he saw fit and to defend and uphold what he believed to be right never failed him. Indeed, so devoted was he to principle and his own ideals that he seems never to have allowed himself one indifferent or careless moment.

He was a man of the strongest local attachments, and seldom wandered beyond his native township. A trip abroad did not tempt him in the least. It would mean in his estimation just so much time lost for enjoying his own village, and he says: “At best, Paris could only be a school in which to learn to live here—a stepping-stone to Concord.”

He had a very pronounced antipathy to the average prosperous city man, and in speaking of persons of this class remarks: “They do a little business commonly each day in order to pay their board, and then they congregate in sitting-rooms, and feebly fabulate and paddle in the social slush, and go unashamed to their beds and take on a new layer of sloth.”

The men he loved were those of a more primitive sort, unartificial, with the daring to cut loose from the trammels of fashion and inherited custom. Especially he liked the companionship of men who were in close contact with nature. A half-wild Irishman, or some rude farmer, or fisherman, or hunter, gave him real delight; and for this reason, Cape Cod appealed to him strongly. It was then a very isolated portion of the State, and its dwellers were just the sort of independent, self-reliant folk to attract him. In his account of his rambles there the human element has large place, and he lingers fondly over the characteristics of his chance acquaintances and notes every salient remark. They, in turn, no doubt found him interesting, too, though the purposes of the wanderer were a good deal of a mystery to them, and they were inclined to think he was a pedler.

His book was the result of several journeys, but the only trip of which he tells us in detail was in October. That month, therefore, was the one I chose for my own visit to the Cape when I went to secure the series of pictures that illustrate this edition; for I wished to see the region as nearly as possible in the same guise that Thoreau describes it. From Sandwich, where his record of Cape experiences begins, and where the inner shore first takes a decided turn eastward, I followed much the same route he had travelled in 1849, clear to Provincetown, at the very tip of the hook.

Thoreau has a good deal to say of the sandy roads and toilsome walking. In that respect there has been marked improvement, for latterly a large proportion of the main highway has been macadamed. Yet one still encounters plenty of the old yielding sand roads that make travel a weariness either on foot or in teams. Another feature to which the nature lover again and again refers is the windmills. The last of these ceased grinding a score of years ago, though several continue to stand in fairly perfect condition. There have been changes on the Cape, but the landscape in the main presents the same appearance it did in Thoreau’s time. As to the people, if you see them in an unconventional way, tramping as Thoreau did, their individuality retains much of the interest that he discovered.

Our author’s report of his trip has a piquancy that is quite alluring. This might be said of all his books, for no matter what he wrote about, his comments were certain to be unusual; and it is as much or more for the revelations of his own tastes, thoughts, and idiosyncrasies that we read him as for the subject matter with which he deals. He had published only two books when he died in 1862 at the age of forty-four, and his “Cape Cod” did not appear until 1865. Nor did the public at first show any marked interest in his books. During his life, therefore, the circle of his admirers was very small, but his fame has steadily increased since, and the stimulus of his lively descriptions and observations seems certain of enduring appreciation.

Clifton Johnson.

Hadley, Mass.

I

THE SHIPWRECK

Wishing to get a better view than I had yet had of the ocean, which, we are told, covers more than two-thirds of the globe, but of which a man who lives a few miles inland may never see any trace, more than of another world, I made a visit to Cape Cod in October, 1849, another the succeeding June, and another to Truro in July, 1855; the first and last time with a single companion, the second time alone. I have spent, in all, about three weeks on the Cape; walked from Eastham to Provincetown twice on the Atlantic side, and once on the Bay side also, excepting four or five miles, and crossed the Cape half a dozen times on my way; but having come so fresh to the sea, I have got but little salted. My readers must expect only so much saltness as the land breeze acquires from blowing over an arm of the sea, or is tasted on the windows and the bark of trees twenty miles inland, after September gales. I have been accustomed to make excursions to the ponds within ten miles of Concord, but latterly I have extended my excursions to the seashore.

I did not see why I might not make a book on Cape Cod, as well as my neighbor on “Human Culture.” It is but another name for the same thing, and hardly a sandier phase of it. As for my title, I suppose that the word Cape is from the French cap; which is from the Latin caput, a head; which is, perhaps, from the verb capere, to take,—that being the part by which we take hold of a thing:—Take Time by the forelock. It is also the safest part to take a serpent by. And as for Cod, that was derived directly from that “great store of codfish” which Captain Bartholomew Gosnold caught there in 1602; which fish appears to have been so called from the Saxon word codde, “a case in which seeds are lodged,” either from the form of the fish, or the quantity of spawn it contains; whence also, perhaps, codling (pomum coctile?) and coddle,—to cook green like peas. (V. Dic.)

Cape Cod is the bared and bended arm of Massachusetts: the shoulder is at Buzzard’s Bay; the elbow, or crazy-bone, at Cape Mallebarre; the wrist at Truro; and the sandy fist at Provincetown,—behind which the State stands on her guard, with her back to the Green Mountains, and her feet planted on the floor of the ocean, like an athlete protecting her Bay,—boxing with northeast storms, and, ever and anon, heaving up her Atlantic adversary from the lap of earth,—ready to thrust forward her other fist, which keeps guard the while upon her breast at Cape Ann.

On studying the map, I saw that there must be an uninterrupted beach on the east or outside of the forearm of the Cape, more than thirty miles from the general line of the coast, which would afford a good sea view, but that, on account of an opening in the beach, forming the entrance to Nauset Harbor, in Orleans, I must strike it in Eastham, if I approached it by land, and probably I could walk thence straight to Race Point, about twenty-eight miles, and not meet with any obstruction.

We left Concord, Massachusetts, on Tuesday, October 9th, 1849. On reaching Boston, we found that the Provincetown steamer, which should have got in the day before, had not yet arrived, on account of a violent storm; and, as we noticed in the streets a handbill headed, “Death! one hundred and forty-five lives lost at Cohasset,” we decided to go by way of Cohasset. We found many Irish in the cars, going to identify bodies and to sympathize with the survivors, and also to attend the funeral which was to take place in the afternoon;—and when we arrived at Cohasset, it appeared that nearly all the passengers were bound for the beach, which was about a mile distant, and many other persons were flocking in from the neighboring country. There were several hundreds of them streaming off over Cohasset common in that direction, some on foot and some in wagons,—and among them were some sportsmen in their hunting-jackets, with their guns, and game-bags, and dogs. As we passed the graveyard we saw a large hole, like a cellar, freshly dug there, and, just before reaching the shore, by a pleasantly winding and rocky road, we met several hay-riggings and farm-wagons coming away toward the meeting-house, each loaded with three large, rough deal boxes. We did not need to ask what was in them. The owners of the wagons were made the undertakers. Many horses in carriages were fastened to the fences near the shore, and, for a mile or more, up and down, the beach was covered with people looking out for bodies, and examining the fragments of the wreck. There was a small island called Brook Island, with a hut on it, lying just off the shore. This is said to be the rockiest shore in Massachusetts, from Nantasket to Scituate,—hard sienitic rocks, which the waves have laid bare, but have not been able to crumble. It has been the scene of many a shipwreck.

The brig St. John, from Galway, Ireland, laden with emigrants, was wrecked on Sunday morning; it was now Tuesday morning, and the sea was still breaking violently on the rocks. There were eighteen or twenty of the same large boxes that I have mentioned, lying on a green hillside, a few rods from the water, and surrounded by a crowd. The bodies which had been recovered, twenty-seven or eight in all, had been collected there. Some were rapidly nailing down the lids, others were carting the boxes away, and others were lifting the lids, which were yet loose, and peeping under the cloths, for each body, with such rags as still adhered to it, was covered loosely with a white sheet. I witnessed no signs of grief, but there was a sober dispatch of business which was affecting. One man was seeking to identify a particular body, and one undertaker or carpenter was calling to another to know in what box a certain child was put. I saw many marble feet and matted heads as the cloths were raised, and one livid, swollen, and mangled body of a drowned girl,—who probably had intended to go out to service in some American family,—to which some rags still adhered, with a string, half concealed by the flesh, about its swollen neck; the coiled-up wreck of a human hulk, gashed by the rocks or fishes, so that the bone and muscle were exposed, but quite bloodless,—merely red and white,—with wide-open and staring eyes, yet lustreless, dead-lights; or like the cabin windows of a stranded vessel, filled with sand. Sometimes there were two or more children, or a parent and child, in the same box, and on the lid would perhaps be written with red chalk, “Bridget such-a-one, and sister’s child.” The surrounding sward was covered with bits of sails and clothing. I have since heard, from one who lives by this beach, that a woman who had come over before, but had left her infant behind for her sister to bring, came and looked into these boxes and saw in one,—probably the same whose superscription I have quoted,—her child in her sister’s arms, as if the sister had meant to be found thus; and within three days after, the mother died from the effect of that sight.

We turned from this and walked along the rocky shore. In the first cove were strewn what seemed the fragments of a vessel, in small pieces mixed with sand and sea-weed, and great quantities of feathers; but it looked so old and rusty, that I at first took it to be some old wreck which had lain there many years. I even thought of Captain Kidd, and that the feathers were those which sea-fowl had cast there; and perhaps there might be some tradition about it in the neighborhood. I asked a sailor if that was the St. John. He said it was. I asked him where she struck. He pointed to a rock in front of us, a mile from the shore, called the Grampus Rock, and added:

“You can see a part of her now sticking up; it looks like a small boat.”

I saw it. It was thought to be held by the chain-cables and the anchors. I asked if the bodies which I saw were all that were drowned.

“Not a quarter of them,” said he.

“Where are the rest?”

“Most of them right underneath that piece you see.”

It appeared to us that there was enough rubbish to make the wreck of a large vessel in this cove alone, and that it would take many days to cart it off. It was several feet deep, and here and there was a bonnet or a jacket on it. In the very midst of the crowd about this wreck, there were men with carts busily collecting the sea-weed which the storm had cast up, and conveying it beyond the reach of the tide, though they were often obliged to separate fragments of clothing from it, and they might at any moment have found a human body under it. Drown who might, they did not forget that this weed was a valuable manure. This shipwreck had not produced a visible vibration in the fabric of society.

About a mile south we could see, rising above the rocks, the masts of the British brig which the St. John had endeavored to follow, which had slipped her cables and, by good luck, run into the mouth of Cohasset Harbor. A little further along the shore we saw a man’s clothes on a rock; further, a woman’s scarf, a gown, a straw bonnet, the brig’s caboose, and one of her masts high and dry, broken into several pieces. In another rocky cove, several rods from the water, and behind rocks twenty feet high, lay a part of one side of the vessel, still hanging together. It was, perhaps, forty feet long, by fourteen wide. I was even more surprised at the power of the waves, exhibited on this shattered fragment, than I had been at the sight of the smaller fragments before. The largest timbers and iron braces were broken superfluously, and I saw that no material could withstand the power of the waves; that iron must go to pieces in such a case, and an iron vessel would be cracked up like an egg-shell on the rocks. Some of these timbers, however, were so rotten that I could almost thrust my umbrella through them. They told us that some were saved on this piece, and also showed where the sea had heaved it into this cove, which was now dry. When I saw where it had come in, and in what condition, I wondered that any had been saved on it. A little further on a crowd of men was collected around the mate of the St. John, who was telling his story. He was a slim-looking youth, who spoke of the captain as the master, and seemed a little excited. He was saying that when they jumped into the boat, she filled, and, the vessel lurching, the weight of the water in the boat caused the painter to break, and so they were separated. Whereat one man came away, saying:—

“Well, I don’t see but he tells a straight story enough. You see, the weight of the water in the boat broke the painter. A boat full of water is very heavy,”—and so on, in a loud and impertinently earnest tone, as if he had a bet depending on it, but had no humane interest in the matter.

Another, a large man, stood near by upon a rock, gazing into the sea, and chewing large quids of tobacco, as if that habit were forever confirmed with him.

“Come,” says another to his companion, “let’s be off. We’ve seen the whole of it. It’s no use to stay to the funeral.”

Further, we saw one standing upon a rock, who, we were told, was one that was saved. He was a sober-looking man, dressed in a jacket and gray pantaloons, with his hands in the pockets. I asked him a few questions, which he answered; but he seemed unwilling to talk about it, and soon walked away. By his side stood one of the life-boatmen, in an oil-cloth jacket, who told us how they went to the relief of the British brig, thinking that the boat of the St. John, which they passed on the way, held all her crew,—for the waves prevented their seeing those who were on the vessel, though they might have saved some had they known there were any there. A little further was the flag of the St. John spread on a rock to dry, and held down by stones at the corners. This frail, but essential and significant portion of the vessel, which had so long been the sport of the winds, was sure to reach the shore. There were one or two houses visible from these rocks, in which were some of the survivors recovering from the shock which their bodies and minds had sustained. One was not expected to live.

We kept on down the shore as far as a promontory called Whitehead, that we might see more of the Cohasset Rocks. In a little cove, within half a mile, there were an old man and his son collecting, with their team, the sea-weed which that fatal storm had cast up, as serenely employed as if there had never been a wreck in the world, though they were within sight of the Grampus Rock, on which the St. John had struck. The old man had heard that there was a wreck, and knew most of the particulars, but he said that he had not been up there since it happened. It was the wrecked weed that concerned him most, rock-weed, kelp, and sea-weed, as he named them, which he carted to his barn-yard; and those bodies were to him but other weeds which the tide cast up, but which were of no use to him. We afterwards came to the life-boat in its harbor, waiting for another emergency,—and in the afternoon we saw the funeral procession at a distance, at the head of which walked the captain with the other survivors.

On the whole, it was not so impressive a scene as I might have expected. If I had found one body cast upon the beach in some lonely place, it would have affected me more. I sympathized rather with the winds and waves, as if to toss and mangle these poor human bodies was the order of the day. If this was the law of Nature, why waste any time in awe or pity? If the last day were come, we should not think so much about the separation of friends or the blighted prospects of individuals. I saw that corpses might be multiplied, as on the field of battle, till they no longer affected us in any degree, as exceptions to the common lot of humanity. Take all the graveyards together, they are always the majority. It is the individual and private that demands our sympathy. A man can attend but one funeral in the course of his life, can behold but one corpse. Yet I saw that the inhabitants of the shore would be not a little affected by this event. They would watch there many days and nights for the sea to give up its dead, and their imaginations and sympathies would supply the place of mourners far away, who as yet knew not of the wreck. Many days after this, something white was seen floating on the water by one who was sauntering on the beach. It was approached in a boat, and found to be the body of a woman, which had risen in an upright position, whose white cap was blown back with the wind. I saw that the beauty of the shore itself was wrecked for many a lonely walker there, until he could perceive, at last, how its beauty was enhanced by wrecks like this, and it acquired thus a rarer and sublimer beauty still.

Cohasset—The little cove at Whitehead promontory

Why care for these dead bodies? They really have no friends but the worms or fishes. Their owners were coming to the New World, as Columbus and the Pilgrims did,—they were within a mile of its shores; but, before they could reach it, they emigrated to a newer world than ever Columbus dreamed of, yet one of whose existence we believe that there is far more universal and convincing evidence—though it has not yet been discovered by science—than Columbus had of this; not merely mariners’ tales and some paltry drift-wood and sea-weed, but a continual drift and instinct to all our shores. I saw their empty hulks that came to land; but they themselves, meanwhile, were cast upon some shore yet further west, toward which we are all tending, and which we shall reach at last, it may be through storm and darkness, as they did. No doubt, we have reason to thank God that they have not been “shipwrecked into life again.” The mariner who makes the safest port in Heaven, perchance, seems to his friends on earth to be shipwrecked, for they deem Boston Harbor the better place; though perhaps invisible to them, a skillful pilot comes to meet him, and the fairest and balmiest gales blow off that coast, his good ship makes the land in halcyon days, and he kisses the shore in rapture there, while his old hulk tosses in the surf here. It is hard to part with one’s body, but, no doubt, it is easy enough to do without it when once it is gone. All their plans and hopes burst like a bubble! Infants by the score dashed on the rocks by the enraged Atlantic Ocean! No, no! If the St. John did not make her port here, she has been telegraphed there. The strongest wind cannot stagger a Spirit; it is a Spirit’s breath. A just man’s purpose cannot be split on any Grampus or material rock, but itself will split rocks till it succeeds.

The verses addressed to Columbus, dying, may, with slight alterations, be applied to the passengers of the St. John:—

“Soon with them will all be over,

Soon the voyage will be begun

That shall bear them to discover,

Far away, a land unknown.

“Land that each, alone, must visit,

But no tidings bring to men;

For no sailor, once departed,

Ever hath returned again.

“No carved wood, no broken branches,

Ever drift from that far wild;

He who on that ocean launches

Meets no corse of angel child.

“Undismayed, my noble sailors,

Spread, then spread your canvas out;

Spirits! on a sea of ether

Soon shall ye serenely float!

“Where the deep no plummet soundeth,

Fear no hidden breakers there,

And the fanning wing of angels

Shall your bark right onward bear.

“Quit, now, full of heart and comfort,

These rude shores, they are of earth;

Where the rosy clouds are parting,

There the blessed isles loom forth.”

One summer day, since this, I came this way, on foot, along the shore from Boston. It was so warm that some horses had climbed to the very top of the ramparts of the old fort at Hull, where there was hardly room to turn round, for the sake of the breeze. The Datura stramonium, or thorn-apple, was in full bloom along the beach; and, at sight of this cosmopolite,—this Captain Cook among plants,—carried in ballast all over the world, I felt as if I were on the highway of nations. Say, rather, this Viking, king of the Bays, for it is not an innocent plant; it suggests not merely commerce, but its attend-ant vices, as if its fibres were the stuff of which pirates spin their yarns. I heard the voices of men shouting aboard a vessel, half a mile from the shore, which sounded as if they were in a barn in the country, they being between the sails. It was a purely rural sound. As I looked over the water, I saw the isles rapidly wasting away, the sea nibbling voraciously at the continent, the springing arch of a hill suddenly interrupted, as at Point Alderton,—what botanists might call premorse,—showing, by its curve against the sky, how much space it must have occupied, where now was water only, On the other hand, these wrecks of isles were being fancifully arranged into new shores, as at Hog Island, inside of Hull, where everything seemed to be gently lapsing, into futurity. This isle had got the very form of a ripple,—and I thought that the inhabitants should bear a ripple for device on their shields, a wave passing over them, with the datura, which is said to produce mental alienation of long duration without affecting the bodily health,[1] springing from its edge. The most interesting thing which I heard of, in this township of Hull, was an unfailing spring, whose locality was pointed out to me, on the side of a distant hill, as I was panting along the shore, though I did not visit it. Perhaps, if I should go through Rome, it would be some spring on the Capitoline Hill I should remember the longest. It is true, I was somewhat interested in the well at the old French fort, which was said to be ninety feet deep, with a cannon at the bottom of it. On Nantasket beach I counted a dozen chaises from the public-house. From time to time the riders turned their horses toward the sea, standing in the water for the coolness,—and I saw the value of beaches to cities for the sea breeze and the bath.

At Jerusalem village the inhabitants were collecting in haste, before a thunder-shower now approaching, the Irish moss which they had spread to dry. The shower passed on one side, and gave me a few drops only, which did not cool the air. I merely felt a puff upon my cheek, though, within sight, a vessel was capsized in the bay, and several others dragged their anchors, and were near going ashore. The sea-bathing at Cohasset Rocks was perfect. The water was purer and more transparent than any I had ever seen. There was not a particle of mud or slime about it. The bottom being sandy, I could see the sea-perch swimming about. The smooth and fantastically worn rocks, and the perfectly clean and tress-like rock-weeds falling over you, and attached so firmly to the rocks that you could pull yourself up by them, greatly enhanced the luxury of the bath. The stripe of barnacles just above the weeds reminded me of some vegetable growth,—the buds, and petals, and seed-vessels of flowers. They lay along the seams of the rock like buttons on a waistcoat. It was one of the hottest days in the year, yet I found the water so icy cold that I could swim but a stroke or two, and thought that, in case of shipwreck, there would be more danger of being chilled to death than simply drowned. One immersion was enough to make you forget the dog-days utterly. Though you were sweltering before, it will take you half an hour now to remember that it was ever warm. There were the tawny rocks, like lions couchant, defying the ocean, whose waves incessantly dashed against and scoured them with vast quantities of gravel. The water held in their little hollows, on the receding of the tide, was so crystalline that I could not believe it salt, but wished to drink it; and higher up were basins of fresh water left by the rain,—all which, being also of different depths and temperature, were convenient for different kinds of baths. Also, the larger hollows in the smoothed rocks formed the most convenient of seats and dressing-rooms. In these respects it was the most perfect seashore that I had seen.

I saw in Cohasset, separated from the sea only by a narrow beach, a handsome but shallow lake of some four hundred acres, which, I was told, the sea had tossed over the beach in a great storm in the spring, and, after the alewives had passed into it, it had stopped up its outlet, and now the alewives were dying: by thousands, and the inhabitants were apprehending a pestilence as the water evaporated. It had live rocky islets in it.

This Rock shore is called Pleasant Cove, on some maps; on the map of Cohasset, that name appears to be confined to the particular cove where I saw the wreck of the St. John. The ocean did not look, now, as if any were ever shipwrecked in it; it was not grand and sublime, but beautiful as a lake. Not a vestige of a wreck was visible, nor could I believe that the bones of many a shipwrecked man were buried in that pure sand. But to go on with our first excursion.

[1] The Jamestown weed (or thorn-apple). “This, being an early plant, was gathered very young for a boiled salad, by some of the soldiers sent thither [i.e. to Virginia] to quell the rebellion of Bacon; and some of them ate plentifully of it, the effect of which was a very pleasant comedy, for they turned natural fools upon it for several days: one would blow up a feather in the air; another would dart straws at it with much fury; and another, stark naked, was sitting up in a corner like a monkey, grinning and making mows at them; a fourth would fondly kiss and paw his companions, and sneer in their faces, with a countenance more antic than any in a Dutch droll. In this frantic condition they were confined, lest they should, in their folly, destroy themselves,—though it was observed that all their actions were full of innocence and good nature. Indeed, they were not very cleanly. A thousand such simple tricks they played, and after eleven days returned to themselves again, not remembering anything that had passed.”—Beverly’s History of Virginia, p. 120.

II

STAGE COACH VIEWS

After spending the night in Bridgewater, and picking up a few arrow-heads there in the morning, we took the cars for Sandwich, where we arrived before noon. This was the terminus of the “Cape Cod Railroad,” though it is but the beginning of the Cape. As it rained hard, with driving mists, and there was no sign of its holding up, we here took that almost obsolete conveyance, the stage, for “as far as it went that day,” as we told the driver. We had forgotten how far a stage could go in a day, but we were told that the Cape roads were very “heavy,” though they added that, being of sand, the rain would improve them. This coach was an exceedingly narrow one, but as there was a slight spherical excess over two on a seat, the driver waited till nine passengers had got in, without taking the measure of any of them, and then shut the door after two or three ineffectual slams, as if the fault were all in the hinges or the latch,—while we timed our inspirations and expirations so as to assist him.

We were now fairly on the Cape, which extends from Sandwich eastward thirty-five miles, and thence north and northwest thirty more, in all sixty-five, and has an average breadth of about five miles. In the interior it rises to the height of two hundred, and sometimes perhaps three hundred feet above the level of the sea. According to Hitchcock, the geologist of the State, it is composed almost entirely of sand, even to the depth of three hundred feet in some places, though there is probably a concealed core of rock a little beneath the surface, and it is of diluvian origin, excepting a small portion at the extremity and elsewhere along the shores, which is alluvial. For the first half of the Cape large blocks of stone are found, here and there, mixed with the sand, but for the last thirty miles boulders, or even gravel, are rarely met with. Hitchcock conjectures that the ocean has, in course of time, eaten out Boston Harbor and other bays in the mainland, and that the minute fragments have been deposited by the currents at a distance from the shore, and formed this sand-bank. Above the sand, if the surface is subjected to agricultural tests, there is found to be a thin layer of soil gradually diminishing from Barnstable to Truro, where it ceases; but there are many holes and rents in this weather-beaten garment not likely to be stitched in time, which reveal the naked flesh of the Cape, and its extremity is completely bare.

I at once got out my book, the eighth volume of the Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, printed in 1802, which contains some short notices of the Cape towns, and began to read up to where I was, for in the cars I could not read as fast as I travelled. To those who came from the side of Plymouth, it said: “After riding through a body of woods, twelve miles in extent, interspersed with but few houses, the settlement of Sandwich appears, with a more agreeable effect, to the eye of the traveller.” Another writer speaks of this as a beautiful village. But I think that our villages will bear to be contrasted only with one another, not with Nature. I have no great respect for the writer’s taste, who talks easily about beautiful villages, embellished, perchance, with a “fulling-mill,” “a handsome academy,” or meeting-house, and “a number of shops for the different mechanic arts”; where the green and white houses of the gentry, drawn up in rows, front on a street of which it would be difficult to tell whether it is most like a desert or a long stable-yard. Such spots can be beautiful only to the weary traveller, or the returning native,—or, perchance, the repentant misanthrope; not to him who, with unprejudiced senses, has just come out of the woods, and approaches one of them, by a bare road, through a succession of straggling homesteads where he cannot tell which is the alms-house. However, as for Sandwich, I cannot speak particularly. Ours was but half a Sandwich at most, and that must have fallen on the buttered side some time. I only saw that it was a closely built town for a small one, with glass-works to improve its sand, and narrow streets in which we turned round and round till we could not tell which way we were going, and the rain came in, first on this side, and then on that, and I saw that they in the houses were more comfortable than we in the coach. My book also said of this town, “The inhabitants, in general, are substantial livers.”—that is. I suppose, they do not live like philosophers: but, as the stage did not stop long enough for us to dine, we had no opportunity to test the truth of this statement. It may have referred, however, to the quantity “of oil they would yield.” It further said, “The inhabitants of Sandwich generally manifest a fond and steady adherence to the manners, employments, and modes of living which characterized their fathers”; which made me think that they were, after all, very much like all the rest of the world;—and it added that this was “a resemblance, which, at this day, will constitute no impeachment of either their virtue or taste”: which remark proves to me that the writer was one with the rest of them. No people ever lived by cursing their fathers, however great a curse their fathers might have been to them. But it must be confessed that ours was old authority, and probably they have changed all that now.

An old windmill

Our route was along the Bay side, through Barnstable, Yarmouth, Dennis, and Brewster, to Orleans, with a range of low hills on our right, running down the Cape. The weather was not favorable for wayside views, but we made the most of such glimpses of land and water as we could get through the rain. The country was, for the most part, bare, or with only a little scrubby wood left on the hills. We noticed in Yarmouth—and, if I do not mistake, in Dennis—large tracts where pitch-pines were planted four or five years before. They were in rows, as they appeared when we were abreast of them, and, excepting that there were extensive vacant spaces, seemed to be doing remarkably well. This, we were told, was the only use to which such tracts could be profitably put. Every higher eminence had a pole set up on it, with an old storm-coat or sail tied to it, for a signal, that those on the south side of the Cape, for instance, might know when the Boston packets had arrived on the north. It appeared as if this use must absorb the greater part of the old clothes of the Cape, leaving but few rags for the pedlers. The wind-mills on the hills,—large weather-stained octagonal structures,—and the salt-works scattered all along the shore, with their long rows of vats resting on piles driven into the marsh, their low, turtle-like roofs, and their slighter wind-mills, were novel and interesting objects to an inlander. The sand by the road-side was partially covered with bunches of a moss-like plant, Hudsonia tomentosa, which a woman in the stage told us was called “poverty-grass,” because it grew where nothing else would.

I was struck by the pleasant equality which reigned among the stage company, and their broad and invulnerable good-humor. They were what is called free and easy, and met one another to advantage, as men who had at length learned how to live. They appeared to know each other when they were strangers, they were so simple and downright. They were well met, in an unusual sense, that is, they met as well as they could meet, and did not seem to be troubled with any impediment. They were not afraid nor ashamed of one another, but were contented to make just such a company as the ingredients allowed. It was evident that the same foolish respect was not here claimed for mere wealth and station that is in many parts of New England; yet some of them were the “first people,” as they are called, of the various towns through which we passed. Retired sea-captains, in easy circumstances, who talked of farming as sea-captains are wont; an erect, respectable, and trustworthy-looking man, in his wrapper, some of the salt of the earth, who had formerly been the salt of the sea; or a more courtly gentleman, who, perchance, had been a representative to the General Court in his day; or a broad, red-faced Cape Cod man, who had seen too many storms to be easily irritated; or a fisherman’s wife, who had been waiting a week for a coaster to leave Boston, and had at length come by the cars.

A strict regard for truth obliges us to say that the few women whom we saw that day looked exceedingly pinched up. They had prominent chins and noses, having lost all their teeth, and a sharp W would represent their profile. They were not so well preserved as their husbands; or perchance they were well preserved as dried specimens. (Their husbands, however, were pickled.) But we respect them not the less for all that; our own dental system is far from perfect.

Still we kept on in the rain, or, if we stopped, it was commonly at a post-office, and we thought that writing letters, and sorting them against our arrival, must be the principal employment of the inhabitants of the Cape this rainy day. The post-office appeared a singularly domestic institution here. Ever and anon the stage stopped before some low shop or dwelling, and a wheelwright or shoemaker appeared in his shirt sleeves and leather apron, with spectacles newly donned, holding up Uncle Sam’s bag, as if it were a slice of home-made cake, for the travellers, while he retailed some piece of gossip to the driver, really as indifferent to the presence of the former as if they were so much baggage. In one instance we understood that a woman was the postmistress, and they said that she made the best one on the road; but we suspected that the letters must be subjected to a very close scrutiny there. While we were stopping for this purpose at Dennis, we ventured to put our heads out of the windows, to see where we were going, and saw rising before us, through the mist, singular barren hills, all stricken with poverty-grass, looming up as if they were in the horizon, though they were close to us, and we seemed to have got to the end of the land on that side, notwithstanding that the horses were still headed that way. Indeed, that part of Dennis which we saw was an exceedingly barren and desolate country, of a character which I can find no name for; such a surface, perhaps, as the bottom of the sea made dry land day before yesterday. It was covered with poverty-grass, and there was hardly a tree in sight, but here and there a little weather-stained, one-storied house, with a red roof,—for often the roof was painted, though the rest of the house was not,—standing bleak and cheerless, yet with a broad foundation to the land, where the comfort must have been all inside. Yet we read in the Gazetteer—for we carried that too with us—that, in 1837, one hundred and fifty masters of vessels, belonging to this town, sailed from the various ports of the Union. There must be many more houses in the south part of the town, else we cannot imagine where they all lodge when they are at home, if ever they are there; but the truth is, their houses are floating ones, and their home is on the ocean. There were almost no trees at all in this part of Dennis, nor could I learn that they talked of setting out any. It is true, there was a meeting-house, set round with Lombardy poplars, in a hollow square, the rows fully as straight as the studs of a building, and the corners as square; but, if I do not mistake, every one of them was dead. I could not help thinking that they needed a revival here. Our book said that, in 1795, there was erected in Dennis “an elegant meeting-house, with a steeple.” Perhaps this was the one; though whether it had a steeple, or had died down so far from sympathy with the poplars, I do not remember. Another meeting-house in this town was described as a “neat building”; but of the meeting-house in Chatham, a neighboring town, for there was then but one, nothing is said, except that it “is in good repair,”—both which remarks, I trust, may be understood as applying to the churches spiritual as well as material. However, “elegant meeting-houses,” from that Trinity one on Broadway, to this at Nobscusset, in my estimation, belong to the same category with “beautiful villages.” I was never in season to see one. Handsome is that handsome does. What they did for shade here, in warm weather, we did not know, though we read that “fogs are more frequent in Chatham than in any other part of the country; and they serve in summer, instead of trees, to shelter the houses against the heat of the sun. To those who delight in extensive vision,”—is it to be inferred that the inhabitants of Chatham do not?—“they are unpleasant, but they are not found to be unhealthful.” Probably, also, the unobstructed sea-breeze answers the purpose of a fan. The historian of Chatham says further, that “in many families there is no difference between the breakfast and supper; cheese, cakes, and pies being as common at the one as at the other.” But that leaves us still uncertain whether they were really common at either.

A street in Sandwich

The road, which was quite hilly, here ran near the Bay-shore, having the Bay on one side, and “the rough hill of Scargo,” said to be the highest land on the Cape, on the other. Of the wide prospect of the Bay afforded by the summit of this hill, our guide says: “The view has not much of the beautiful in it, but it communicates a strong emotion of the sublime.” That is the kind of communication which we love to have made to us. We passed through the village of Suet, in Dennis, on Suet and Quivet Necks, of which it is said, “when compared with Nobscusset,”—we had a misty recollection of having passed through, or near to, the latter,—“it may be denominated a pleasant village; but, in comparison with the village of Sandwich, there is little or no beauty in it.” However, we liked Dennis well, better than any town we had seen on the Cape, it was so novel, and, in that stormy day, so sublimely dreary.

Captain John Sears, of Suet, was the first person in this country who obtained pure marine salt by solar evaporation alone; though it had long been made in a similar way on the coast of France, and elsewhere. This was in the year 1776, at which time, on account of the war, salt was scarce and dear. The Historical Collections contain an interesting account of his experiments, which we read when we first saw the roofs of the salt-works. Barnstable county is the most favorable locality for these works on our northern coast,—there is so little fresh water here emptying into ocean. Quite recently there were about two millions of dollars invested in this business here. But now the Cape is unable to compete with the importers of salt and the manufacturers of it at the West, and, accordingly, her salt-works are fast going to decay. From making salt, they turn to fishing more than ever. The Gazetteer will uniformly tell you, under the head of each town, how many go a-fishing, and the value of the fish and oil taken, how much salt is made and used, how many are engaged in the coasting trade, how many in manufacturing palm-leaf hats, leather, boots, shoes, and tinware, and then it has done, and leaves you to imagine the more truly domestic manufactures which are nearly the same all the world over.

Late in the afternoon, we rode through Brewster, so named after Elder Brewster, for fear he would be forgotten else. Who has not heard of Elder Brewster? Who knows who he was? This appeared to be the modern-built town of the Cape, the favorite residence of retired sea-captains. It is said that “there are more masters and mates of vessels which sail on foreign voyages belonging to this place than to any other town in the country.” There were many of the modern American houses here, such as they turn out at Cambridgeport, standing on the sand; you could almost swear that they had been floated down Charles River, and drifted across the Bay. I call them American, because they are paid for by Americans, and “put up” by American carpenters; but they are little removed from lumber; only Eastern stuff disguised with white paint, the least interesting kind of drift-wood to me. Perhaps we have reason to be proud of our naval architecture, and need not go to the Greeks, or the Goths, or the Italians, for the models of our vessels. Sea-captains do not employ a Cambridgeport carpenter to build their floating houses, and for their houses on shore, if they must copy any, it would be more agreeable to the imagination to see one of their vessels turned bottom upward, in the Numidian fashion. We read that, “at certain seasons, the reflection of the sun upon the windows of the houses in Wellfleet and Truro (across the inner side of the elbow of the Cape) is discernible with the naked eye, at a distance of eighteen miles and upward, on the county road.” This we were pleased to imagine, as we had not seen the sun for twenty-four hours.

The old Higgins tavern at Orleans

The same author (the Rev. John Simpkins) said of the inhabitants, a good while ago: “No persons appear to have a greater relish for the social circle and domestic pleasures. They are not in the habit of frequenting taverns, unless on public occasions. I know not of a proper idler or tavern-haunter in the place.” This is more than can be said of my townsmen.

At length we stopped for the night at Higgins’s tavern, in Orleans, feeling very much as if we were on a sand-bar in the ocean, and not knowing whether we should see land or water ahead when the mist cleared away. We here overtook two Italian boys, who had waded thus far down the Cape through the sand, with their organs on their backs, and were going on to Provincetown. What a hard lot, we thought, if the Provincetown people should shut their doors against them! Whose yard would they go to next? Yet we concluded that they had chosen wisely to come here, where other music than that of the surf must be rare. Thus the great civilizer sends out its emissaries, sooner or later, to every sandy cape and light-house of the New World which the census-taker visits, and summons the savage there to surrender.

III

THE PLAINS OF NAUSET

The next morning, Thursday, October 11th, it rained, as hard as ever; but we were determined to proceed on foot, nevertheless. We first made some inquiries with regard to the practicability of walking up the shore on the Atlantic side to Provincetown, whether we should meet with any creeks or marshes to trouble us. Higgins said that there was no obstruction, and that it was not much farther than by the road, but he thought that we should find it very “heavy” walking in the sand; it was bad enough in the road, a horse would sink in up to the fetlocks there. But there was one man at the tavern who had walked it, and he said that we could go very well, though it was sometimes inconvenient and even dangerous walking under the bank, when there was a great tide, with an easterly wind, which caused the sand to cave. For the first four or five miles we followed the road, which here turns to the north on the elbow, —the narrowest part of the Cape,—that we might clear an inlet from the ocean, a part of Nauset Harbor, in Orleans, on our right. We found the travelling good enough for walkers on the sides of the roads, though it was “heavy” for horses in the middle. We walked with our umbrellas behind us, since it blowed hard as well as rained, with driving mists, as the day before, and the wind helped us over the sand at a rapid rate. Everything indicated that we had reached a strange shore. The road was a mere lane, winding over bare swells of bleak and barren-looking land. The houses were few and far between, besides being small and rusty, though they appeared to be kept in good repair, and their dooryards, which were the unfenced Cape, were tidy; or, rather, they looked as if the ground around them was blown clean by the wind. Perhaps the scarcity of wood here, and the consequent absence of the wood-pile and other wooden traps, had something to do with this appearance. They seemed, like mariners ashore, to have sat right down to enjoy the firmness of the land, without studying their postures or habiliments. To them it was merely terra firma and cognita, not yet fertilis and jucunda. Every landscape which is dreary enough has a certain beauty to my eyes, and in this instance its permanent qualities were enhanced by the weather. Everything told of the sea, even when we did not see its waste or hear its roar. For birds there were gulls, and for carts in the fields, boats turned bottom upward against the houses, and sometimes the rib of a whale was woven into the fence by the road-side. The trees were, if possible, rarer than the houses, excepting apple-trees, of which there were a few small orchards in the hollows. These were either narrow and high, with flat tops, having lost their side branches, like huge plum-bushes growing in exposed situations, or else dwarfed and branching immediately at the ground, like quince-bushes. They suggested that, under like circumstances, all trees would at last acquire like habits of growth. I afterward saw on the Cape many full-grown apple-trees not higher than a man’s head; one whole orchard, indeed, where all the fruit could have been gathered by a man standing on the ground; but you could hardly creep beneath the trees. Some, which the owners told me were twenty years old, were only three and a half feet high, spreading at six inches from the ground five feet each way, and being withal surrounded with boxes of tar to catch the cankerworms, they looked like plants in flower-pots, and as if they might be taken into the house in the winter. In another place, I saw some not much larger than currant-bushes; yet the owner told me that they had borne a barrel and a half of apples that fall. If they had been placed close together, I could have cleared them all at a jump. I measured some near the Highland Light in Truro, which had been taken from the shrubby woods thereabouts when young, and grafted. One, which had been set ten years, was on an average eighteen inches high, and spread nine feet with a flat top. It had borne one bushel of apples two years before. Another, probably twenty years old from the seed, was five feet high, and spread eighteen feet, branching, as usual, at the ground, so that you could not creep under it. This bore a barrel of apples two years before. The owner of these trees invariably used the personal pronoun in speaking of them; as, “I got him out of the woods, but he doesn’t bear.” The largest that I saw in that neighborhood was nine feet high to the topmost leaf, and spread thirty-three feet, branching at the ground five ways.

A Nauset lane

In one yard I observed a single, very healthy-looking tree, while all the rest were dead or dying. The occupant said that his father had manured all but that one with blackfish.

This habit of growth should, no doubt, be encouraged; and they should not be trimmed up, as some travelling practitioners have advised. In 1802 there was not a single fruit-tree in Chatham, the next town to Orleans, on the south; and the old account of Orleans says: “Fruit-trees cannot be made to grow within a mile of the ocean. Even those which are placed at a greater distance are injured by the east winds; and, after violent storms in the spring, a saltish taste is perceptible on their bark.” We noticed that they were often covered with a yellow lichen-like rust, the Parmelia parietina.

The most foreign and picturesque structures on the Cape, to an inlander, not excepting the salt-works, are the wind-mills,—gray-looking octagonal towers, with long timbers slanting to the ground in the rear, and there resting on a cart-wheel, by which their fans are turned round to face the wind. These appeared also to serve in some measure for props against its force. A great circular rut was worn around the building by the wheel. The neighbors who assemble to turn the mill to the wind are likely to know which way it blows, without a weathercock. They looked loose and slightly locomotive, like huge wounded birds, trailing a wing or a leg, and re-minded one of pictures of the Netherlands. Being on elevated ground, and high in themselves, they serve as landmarks,—for there are no tall trees, or other objects commonly, which can be seen at a distance in the horizon; though the outline of the land itself is so firm and distinct that an insignificant cone, or even precipice of sand, is visible at a great distance from over the sea. Sailors making the land commonly steer either by the wind-mills or the meeting-houses. In the country, we are obliged to steer by the meeting-houses alone. Yet the meeting-house is a kind of wind-mill, which runs one day in seven, turned either by the winds of doctrine or public opinion, or more rarely by the winds of Heaven, where another sort of grist is ground, of which, if it be not all bran or musty, if it be not plaster, we trust to make bread of life.

There were, here and there, heaps of shells in the fields, where clams had been opened for bait; for Orleans is famous for its shell-fish, especially clams, or, as our author says, “to speak more properly, worms.” The shores are more fertile than the dry land. The inhabitants measure their crops, not only by bushels of corn, but by barrels of clams. A thousand barrels of clam-bait are counted as equal in value to six or eight thousand bushels of Indian corn, and once they were procured without more labor or expense, and the supply was thought to be inexhaustible. “For,” runs the history, “after a portion of the shore has been dug over, and almost all the clams taken up, at the end of two years, it is said, they are as plenty there as ever. It is even affirmed by many persons, that it is as necessary to stir the clam ground frequently as it is to hoe a field of potatoes; because, if this labor is omitted, the clams will be crowded too closely together, and will be prevented from increasing in size.” But we were told that the small clam, Mya arenaria, was not so plenty here as formerly. Probably the clam ground has been stirred too frequently, after all. Nevertheless, one man, who complained that they fed pigs with them and so made them scarce, told me that he dug and opened one hundred and twenty-six dollars’ worth in one winter, in Truro.

Nauset Bay

We crossed a brook, not more than fourteen rods long, between Orleans and Eastham, called Jeremiah’s Gutter. The Atlantic is said sometimes to meet the Bay here, and isolate the northern part of the Cape. The streams of the Cape are necessarily formed on a minute scale, since there is no room for them to run, without tumbling immediately into the sea; and beside, we found it difficult to run ourselves in that sand, when there was no want of room. Hence, the least channel where water runs, or may run, is important, and is dignified with a name. We read that there is no running water in Chatham, which is the next town. The barren aspect of the land would hardly be believed if described. It was such soil, or rather land, as, to judge from appearances, no farmer in the interior would think of cultivating, or even fencing. Generally, the ploughed fields of the Cape look white and yellow, like a mixture of salt and Indian meal. This is called soil. All an inlander’s notions of soil and fertility will be confounded by a visit to these parts, and he will not be able, for some time afterward, to distinguish soil from sand. The historian of Chatham says of a part of that town, which has been gained from the sea: “There is a doubtful appearance of a soil beginning to be formed. It is styled doubtful, because it would not be observed by every eye, and perhaps not acknowledged by many.” We thought that this would not be a bad description of the greater part of the Cape. There is a “beach” on the west side of Eastham, which we crossed the next summer, half a mile wide, and stretching across the township, containing seventeen hundred acres, on which there is not now a particle of vegetable mould, though it formerly produced wheat. All sands are here called “beaches,” whether they are waves of water or of air that dash against them, since they commonly have their origin on the shore. “The sand in some places,” says the historian of Eastham, “lodging against the beach-grass, has been raised into hills fifty feet high, where twenty-five years ago no hills existed. In others it has filled up small valleys, and swamps. Where a strong-rooted bush stood, the appearance is singular: a mass of earth and sand adheres to it, resembling a small tower. In several places, rocks, which were formerly covered with soil, are disclosed, and being lashed by the sand, driven against them by the wind, look as if they were recently dug from a quarry.”

We were surprised to hear of the great crops of corn which are still raised in Eastham, notwithstanding the real and apparent barrenness. Our landlord in Orleans had told us that he raised three or four hundred bushels of corn annually, and also of the great number of pigs which he fattened. In Champlain’s “Voyages,” there is a plate representing the Indian cornfields hereabouts, with their wigwams in the midst, as they appeared in 1605, and it was here that the Pilgrims, to quote their own words, “bought eight or ten hogsheads of corn and beans” of the Nauset Indians, in 1622, to keep themselves from starving.[1]

“In 1667 the town [of Eastham] voted that every housekeeper should kill twelve blackbirds or three crows, which did great damage to the corn; and this vote was repeated for many years.” In 1695 an additional order was passed, namely, that “every unmarried man in the township shall kill six blackbirds, or three crows, while he remains single; as a penalty for not doing it, shall not be married until he obey this order.” The blackbirds, however, still molest the corn. I saw them at it the next summer, and there were many scarecrows, if not scare-blackbirds, in the fields, which I often mistook for men.

A scarecrow

From which I concluded that either many men were not married, or many blackbirds were. Yet they put but three or four kernels in a hill, and let fewer plants remain than we do. In the account of Eastham, in the “Historical Collections,” printed in 1802, it is said, that “more corn is produced than the inhabitants consume, and about a thousand bushels are annually sent to market. The soil being free from stones, a plough passes through it speedily; and after the corn has come up, a small Cape horse, somewhat larger than a goat, will, with the assistance of two boys, easily hoe three or four acres in a day; several farmers are accustomed to produce five hundred bushels of grain annually, and not long since one raised eight hundred bushels on sixty acres.” Similar accounts are given to-day; indeed, the recent accounts are in some instances suspectable repetitions of the old, and I have no doubt that their statements are as often founded on the exception as the rule, and that by far the greater number of acres are as barren as they appear to be. It is sufficiently remarkable that any crops can be raised here, and it may be owing, as others have suggested, to the amount of moisture in the atmosphere, the warmth of the sand, and the rareness of frosts. A miller, who was sharpening his stones, told me that, forty years ago, he had been to a husking here, where five hundred bushels were husked in one evening, and the corn was piled six feet high or more, in the midst, but now, fifteen or eighteen bushels to an acre were an average yield. I never saw fields of such puny and unpromising looking corn as in this town. Probably the inhabitants are contented with small crops from a great surface easily cultivated. It is not always the most fertile land that is the most profitable, and this sand may repay cultivation, as well as the fertile bottoms of the West. It is said, moreover, that the vegetables raised in the sand, without manure, are remarkably sweet, the pumpkins especially, though when their seed is planted in the interior they soon degenerate. I can testify that the vegetables here, when they succeed at all, look remarkably green and healthy, though perhaps it is partly by contrast with the sand. Yet the inhabitants of the Cape towns, generally, do not raise their own meal or pork. Their gardens are commonly little patches, that have been redeemed from the edges of the marshes and swamps.

All the morning we had heard the sea roar on the eastern shore, which was several miles distant; for it still felt the effects of the storm in which the St. John was wrecked,—though a school-boy, whom we overtook, hardly knew what we meant, his ears were so used to it. He would have more plainly heard the same sound in a shell. It was a very inspiriting sound to walk by, filling the whole air, that of the sea dashing against the land, heard several miles inland. Instead of having a dog to growl before your door, to have an Atlantic Ocean to growl for a whole Cape! On the whole, we were glad of the storm, which would show us the ocean in its angriest mood. Charles Darwin was assured that the roar of the surf on the coast of Chiloe, after a heavy gale, could be heard at night a distance of “21 sea miles across a hilly and wooded country.” We conversed with the boy we have mentioned, who might have been eight years old, making him walk the while under the lee of our umbrella; for we thought it as important to know what was life on the Cape to a boy as to a man. We learned from him where the best grapes were to be found in that neighborhood. He was carrying his dinner in a pail; and, without any impertinent questions being put by us, it did at length appear of what it consisted. The homeliest facts are always the most acceptable to an inquiring mind. At length, before we got to Eastham meeting-house, we left the road and struck across the country for the eastern shore at Nauset Lights,—three lights close together, two or three miles distant from us. They were so many that they might be distinguished from others; but this seemed a shiftless and costly way of accomplishing that object. We found ourselves at once on an apparently boundless plain, without a tree or a fence, or, with one or two exceptions, a house in sight. Instead of fences, the earth was sometimes thrown up into a slight ridge. My companion compared it to the rolling prairies of Illinois. In the storm of wind and rain which raged when we traversed it, it no doubt appeared more vast and desolate than it really is. As there were no hills, but only here and there a dry hollow in the midst of the waste, and the distant horizon was concealed by mist, we did not know whether it was high or low. A solitary traveller whom we saw perambulating in the distance loomed like a giant. He appeared to walk slouchingly, as if held up from above by straps under his shoulders, as much as supported by the plain below. Men and boys would have appeared alike at a little distance, there being no object by which to measure them. Indeed, to an inlander, the Cape landscape is a constant mirage. This kind of country extended a mile or two each way. These were the “Plains of Nauset,” once covered with wood, where in winter the winds howl and the snow blows right merrily in the face of the traveller. I was glad to have got out of the towns, where I am wont to feel unspeakably mean and disgraced,—to have left behind me for a season the bar-rooms of Massachusetts, where the full-grown are not weaned from savage and filthy habits,—still sucking a cigar. My spirits rose in proportion to the outward dreariness. The towns need to be ventilated. The gods would be pleased to see some pure flames from their altars. They are not to be appeased with cigar-smoke.

As we thus skirted the back-side of the towns, for we did not enter any village, till we got to Provincetown, we read their histories under our umbrellas, rarely meeting anybody. The old accounts are the richest in topography, which was what we wanted most; and, indeed, in most things else, for I find that the readable parts of the modern accounts of these towns consist, in a great measure, of quotations, acknowledged and unacknowledged, from the older ones, without any additional information of equal interest;—town histories, which at length run into a history of the Church of that place, that being the only story they have to tell, and conclude by quoting the Latin epitaphs of the old pastors, having been written in the good old days of Latin and of Greek. They will go back to the ordination of every minister and tell you faithfully who made the introductory prayer, and who delivered the sermon; who made the ordaining prayer, and who gave the charge; who extended the right hand of fellowship, and who pronounced the benediction; also how many ecclesiastical councils convened from time to time to inquire into the orthodoxy of some minister, and the names of all who composed them. As it will take us an hour to get over this plain, and there is no variety in the prospect, peculiar as it is, I will read a little in the history of Eastham the while.

When the committee from Plymouth had purchased the territory of Eastham of the Indians, “it was demanded, who laid claim to Billingsgate?” which was understood to be all that part of the Cape north of what they had purchased. “The answer was, there was not any who owned it. ‘Then,’ said the committee, ‘that land is ours.’ The Indians answered, that it was.” This was a remarkable assertion and admission. The Pilgrims appear to have regarded themselves as Not Any’s representatives. Perhaps this was the first instance of that quiet way of “speaking for” a place not yet occupied, or at least not improved as much as it may be, which their descendants have practised, and are still practising so extensively. Not Any seems to have been the sole proprietor of all America before the Yankees. But history says that, when the Pilgrims had held the lands of Billingsgate many years, at length “appeared an Indian, who styled himself Lieutenant Anthony,” who laid claim to them, and of him they bought them. Who knows but a Lieutenant Anthony may be knocking at the door of the White House some day? At any rate, I know that if you hold a thing unjustly, there will surely be the devil to pay at last.

Thomas Prince, who was several times the governor of the Plymouth colony, was the leader of the settlement of Eastham. There was recently standing, on what was once his farm, in this town, a pear-tree which is said to have been brought from England, and planted there by him, about two hundred years ago. It was blown down a few months before we were there. A late account says that it was recently in a vigorous state; the fruit small, but excellent; and it yielded on an average fifteen bushels. Some appropriate lines have been addressed to it, by a Mr. Heman Doane, from which I will quote, partly because they are the only specimen of Cape Cod verse which I remember to have seen, and partly because they are not bad.

“Two hundred years have, on the wings of Time,

Passed with their joys and woes, since thou, Old Tree!

Put forth thy first leaves in this foreign clime.

Transplanted from the soil beyond the sea.”

* * * * *

[These stars represent the more clerical lines, and also those which have deceased.]

“That exiled band long since have passed away,

And still, Old Tree I thou standest in the place

Where Prince’s hand did plant thee in his day,—

An undesigned memorial of his race

And time; of those our honored fathers,

when They came from Plymouth o’er and settled here;

Doane, Higgins, Snow, and other worthy men.

Whose names their sons remember to revere.

* * * * *

“Old Time has thinned thy boughs. Old Pilgrim Tree!

And bowed thee with the weight of many years;

Yet ’mid the frosts of age, thy bloom we see,

And yearly still thy mellow fruit appears.”

There are some other lines which I might quote, if they were not tied to unworthy companions by the rhyme. When one ox will lie down, the yoke bears hard on him that stands up.

One of the first settlers of Eastham was Deacon John Doane, who died in 1707, aged one hundred and ten. Tradition says that he was rocked in a cradle several of his last years. That, certainly, was not an Achillean life. His mother must have let him slip when she dipped him into the liquor which was to make him invulnerable, and he went in, heels and all. Some of the stone-bounds to his farm which he set up are standing to-day, with his initials cut in them.

The ecclesiastical history of this town interested us somewhat. It appears that “they very early built a small meeting-house, twenty feet square, with a thatched roof through which they might fire their muskets,”—of course, at the Devil. “In 1662, the town agreed that a part of every whale cast on shore be appropriated for the support of the ministry.” No doubt there seemed to be some propriety in thus leaving the support of the ministers to Providence, whose servants they are, and who alone rules the storms; for, when few whales were cast up, they might suspect that their worship was not acceptable. The ministers must have sat upon the cliffs in every storm, and watched the shore with anxiety. And, for my part, if I were a minister I would rather trust to the bowels of the billows, on the back-side of Cape Cod, to cast up a whale for me, than to the generosity of many a country parish that I know. You cannot say of a country minister’s salary, commonly, that it is “very like a whale.” Nevertheless, the minister who depended on whales cast up must have had a trying time of it. I would rather have gone to the Falkland Isles with a harpoon, and done with it. Think of a whale having the breath of life beaten out of him by a storm, and dragging in over the bars and guzzles, for the support of the ministry! What a consolation it must have been to him! I have heard of a minister, who had been a fisherman, being settled in Bridgewater for as long a time as he could tell a cod from a haddock. Generous as it seems, this condition would empty most country pulpits forthwith, for it is long since the fishers of men were fishermen. Also, a duty was put on mackerel here to support a free-school; in other words, the mackerel-school was taxed in order that the children’s school might be free. “In 1665 the Court passed a law to inflict corporal punishment on all persons, who resided in the towns of this government, who denied the Scriptures.” Think of a man being whipped on a spring morning till he was constrained to confess that the Scriptures were true! “It was also voted by the town that all persons who should stand out of the meeting-house during the time of divine service should be set in the stocks.” It behooved such a town to see that sitting in the meeting-house was nothing akin to sitting in the stocks, lest the penalty of obedience to the law might be greater than that of disobedience. This was the Eastham famous of late years for its camp-meetings, held in a grove near by, to which thousands flock from all parts of the Bay. We conjectured that the reason for the perhaps unusual, if not unhealthful, development of the religious sentiment here was the fact that a large portion of the population are women whose husbands and sons are either abroad on the sea, or else drowned, and there is nobody but they and the ministers left behind. The old account says that “hysteric fits are very common in Orleans, Eastham, and the towns below, particularly on Sunday, in the times of divine service. When one woman is affected, five or six others generally sympathize with her; and the congregation is thrown into the utmost confusion. Several old men suppose, unphilosophically and uncharitably, perhaps, that the will is partly concerned, and that ridicule and threats would have a tendency to prevent the evil.” How this is now we did not learn. We saw one singularly masculine woman, however, in a house on this very plain, who did not look as if she was ever troubled with hysterics, or sympathized with those that were; or, perchance, life itself was to her a hysteric fit,—a Nauset woman, of a hardness and coarseness such as no man ever possesses or suggests. It was enough to see the vertebrae and sinews of her neck, and her set jaws of iron, which would have bitten a board-nail in two in their ordinary action,—braced against the world, talking like a man-of-war’s-man in petticoats, or as if shouting to you through a breaker; who looked as if it made her head ache to live; hard enough for any enormity. I looked upon her as one who had committed infanticide; who never had a brother, unless it were some wee thing that died in infancy,—for what need of him?—and whose father must have died before she was born. This woman told us that the camp-meetings were not held the previous summer for fear of introducing the cholera, and that they would have been held earlier this summer, but the rye was so backward that straw would not have been ready for them; for they lie in straw. There are sometimes one hundred and fifty ministers (!) and five thousand hearers assembled. The ground, which is called Millennium Grove, is owned by a company in Boston, and is the most suitable, or rather unsuitable, for this purpose of any that I saw on the Cape. It is fenced, and the frames of the tents are at all times to be seen interspersed among the oaks. They have an oven and a pump, and keep all their kitchen utensils and tent coverings and furniture in a permanent building on the spot. They select a time for their meetings when the moon is full. A man is appointed to clear out the pump a week beforehand, while the ministers are clearing their throats; but, probably, the latter do not always deliver as pure a stream as the former. I saw the heaps of clam-shells left under the tables, where they had feasted in previous summers, and supposed, of course, that that was the work of the unconverted, or the backsliders and scoffers. It looked as if a camp-meeting must be a singular combination of a prayer-meeting and a picnic.

Millennium Grove camp-meeting grounds

The first minister settled here was the Rev. Samuel Treat, in 1672, a gentleman who is said to be “entitled to a distinguished rank among the evangelists of New England.” He converted many Indians, as well as white men, in his day, and translated the Confession of Faith into the Nauset language. These were the Indians concerning whom their first teacher, Richard Bourne, wrote to Gookin, in 1674, that he had been to see one who was sick, “and there came from him very savory and heavenly expressions,” but, with regard to the mass of them, he says, “the truth is, that many of them are very loose in their course, to my heartbreaking sorrow.” Mr. Treat is described as a Calvinist of the strictest kind, not one of those who, by giving up or explaining away, become like a porcupine disarmed of its quills, but a consistent Calvinist, who can dart his quills to a distance and courageously defend himself. There exists a volume of his sermons in manuscript, “which,” says a commentator, “appear to have been designed for publication.” I quote the following sentences at second hand, from a Discourse on Luke xvi. 23, addressed to sinners:—

“Thou must erelong go to the bottomless pit. Hell hath enlarged herself, and is ready to receive thee. There is room enough for thy entertainment....