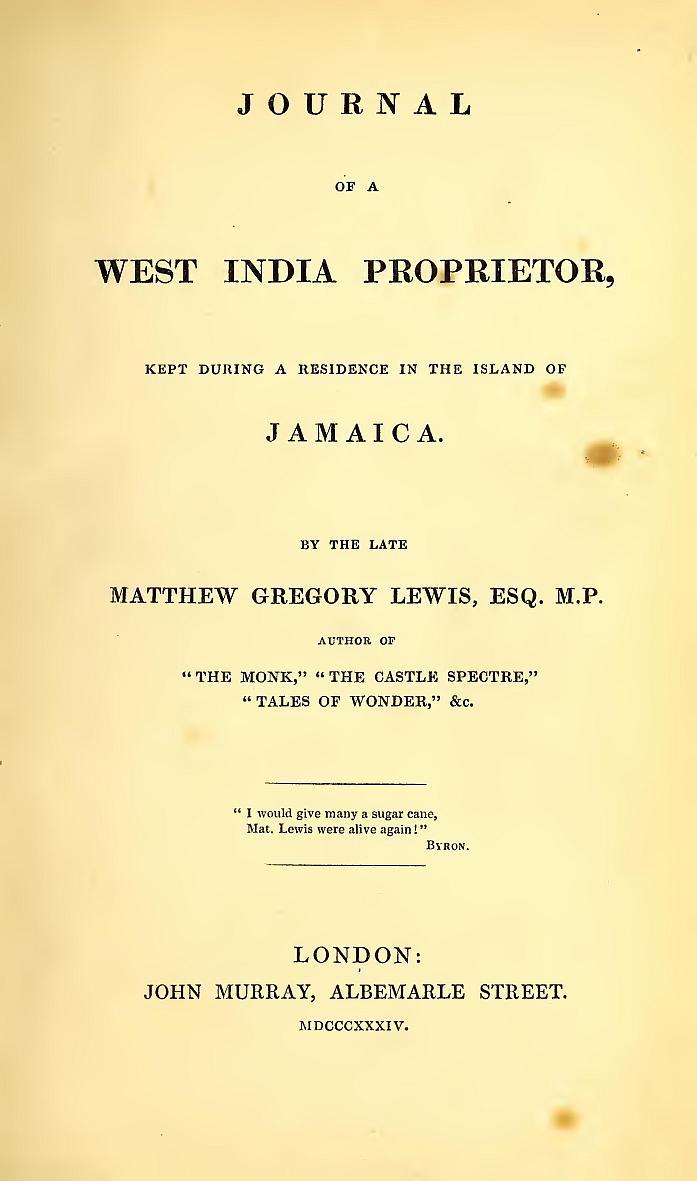

Journal of a West India Proprietor

M. G. Lewis

JOURNAL OF A WEST INDIA PROPRIETOR,

Kept During a Residence in The Island of Jamaica

By Matthew Gregory Lewis

Author of “The Monk,” “The Castle Spectre,” “Tales Of Wonder,” &c.

London: John Murray, Albemarle Street.

MDCCCXXXIV

“I WOULD GIVE MANY A SUGAR CANE,

MAT. LEWIS WERE ALIVE AGAIN!”

BYRON.

CONTENTS

ADVERTISEMENT.

JOURNAL OF A WEST INDIA PROPRIETOR

1815. NOVEMBER 8.

1816.—JANUARY 1.

1817.

1818.—JANUARY 1.

ADVERTISEMENT.

The following Journals of two residences in Jamaica, in 1815-16, and in 1817, are now printed from the MS. of Mr. Lewis; who died at sea, on the voyage homewards from the West Indies, in the year 1818.

JOURNAL OF A WEST INDIA PROPRIETOR

Expect our sailing in a few hours. But although the vessel left the Docks on Saturday, she did not reach this place till three o’clock on Thursday, the 9th. The captain now tells me, that we may expect to sail certainly in the afternoon of to-morrow, the 10th. I expect the ship’s cabin to gain greatly by my two days’ residence at the “———————,” which nothing can exceed for noise, dirt, and dulness. Eloisa would never have established “black melancholy” at the Paraclete as its favourite residence, if she had happened to pass three days at an inn at Gravesend: nowhere else did I ever see the sky look so dingy, and the river “Nunc alio patriam quaero sub sole jacentem.”—Virgil.

1815. NOVEMBER 8.

(WEDNESDAY)

I left London, and reached Gravesend at nine in the morning, having been taught to exso dirty; to be sure, the place has all the advantages of an English November to assist it in those particulars. Just now, too, a carriage passed my windows, conveying on board a cargo of passengers, who seemed sincerely afflicted at the thoughts of leaving their dear native land! The pigs squeaked, the ducks quacked, and the fowls screamed; and all so dolefully, as clearly to prove, that theirs was no dissembled sorrow? And after them (more affecting than all) came a wheelbarrow, with a solitary porker tied in a basket, with his head hanging over on one side, and his legs sticking out on the other, who neither grunted nor moved, nor gave any signs of life, but seemed to be of quite the same opinion with Hannah More’s heroine, “Grief is for little wrongs; despair for mine!”

As Miss O’Neil is to play “Elwina” for the first time to-morrow, it is a thousand pities that she had not the previous advantage of seeing the speechless despondency of this poor pig; it might have furnished her with some valuable hints, and enabled her to convey more perfectly to the audience the “expressive silence” of irremediable distress.

NOVEMBER 10.

At four o’clock in the afternoon, I embarked on board the “Sir Godfrey Webster,” Captain Boyes. On approaching the vessel, we heard the loudest of all possible shrieks proceeding from a boat lying near her: and who should prove to be the complainant, but my former acquaintance, the despairing pig, He had recovered his voice to protest against entering the ship: I had already declared against climbing up the accommodation ladder; the pig had precisely the very same objection. So a soi-disant chair, being a broken bucket, was let down for us, and the pig and myself entered the vessel by the same conveyance; only pig had the precedence, and was hoisted up first. The ship proceeded three miles, and then the darkness obliged us to come to an anchor. There are only two other cabin passengers, a Mr. J——— and a Mr. S———; the latter is a planter in the “May-Day Mountains,” Jamaica: he wonders, considering how much benefit Great Britain derives from the West Indies, that government is not careful to build more churches in them, and is of opinion, that “hedicating the negroes is the only way to make them appy; indeed, in his umble hopinion, hedication his hall in hall!”

NOVEMBER 11.

We sailed at six o’clock, passed through “Nob’s Hole,” the “Girdler’s Hole,” and “the Pan” (all very dangerous sands, and particularly the last, where at times we had only one foot water below us), by half past four, and at five came to an anchor in the Queen’s Channel. Never having seen any thing of the kind before, I was wonderfully pleased with the manoeuvring of several large ships, which passed through the sands at the same time with us: their motions seemed to be effected with as much ease and dexterity as if they had been crane-necked carriages; and the effect as they pursued each other’s track and windings was perfectly beautiful.

NOVEMBER 12. (SUNDAY.)

The wind was contrary, and we had to beat up the whole way; we did not reach the Downs till past four o’clock, and, as there were above sixty vessels arrived before us, we had some difficulty in finding a safe berth. At length we anchored in the Lower Roads, about four miles off Deal. We can see very clearly the double lights in the vessel moored off the Goodwin sands: it is constantly inhabited by two families, who reside there alternately every fortnight, except when the weather delays the exchange. The “Sir Godfrey Webster” is a vessel of 600 tons, and was formerly in the East India service. I have a very clean cabin, a place for my books, and every thing is much more comfortable than I expected; the wind, however, is completely west, the worst that we could have, and we must not even expect a change till the full moon. The captain pointed out a man to me to-day, who had been with him in a violent storm off the Bermudas. For six hours together, the flashes of lightning were so unintermitting, that the eye could not sustain them: at one time, the ship seemed to be completely in a blaze; and the man in question (who was then standing at the wheel, near the captain) suddenly cried out, “I don’t know what has happened to me, but I can neither see nor stand;” and he fell down upon the deck. He was taken up and carried below; and it appeared that the lightning had affected his eyes and legs, in a degree to make him both blind and lame, though the captain, who was standing by his side, had received no injury: in three or four days, the man was quite well again. In this storm, no less than thirteen vessels were dismasted, or otherwise shattered by the lightning.

Sea Terms.—Windward, from whence the wind blows; leeward, to which it blows; starboard, the right of the stern; larboard, the left; starboard helm, when you go to the left; but when to the right, instead of larboard helm, helm a-port; luff you may, go nearer to the wind; theis (thus) you are near enough; luff no near, you are too near the wind; the tiller, the handle of the rudder; the capstan, the weigher of the anchor; the buntlines, the ropes which move the body of the sail, the bunt being the body; the bowlines, those which spread out the sails, and make them swell.

NOVEMBER 13.

At six this morning, came on a tremendous gale of wind; the captain says, that he never experienced a heavier. However, we rode it out with great success, although, at one time, it was bawled out that we were driving; and, at another, a brig which lay near us broke from her moorings, and came bearing down close upon us. The danger, indeed, from the difference of size, was all upon the side of the brig; but, luckily, the vessels cleared each other. This evening she has thought it as well to remove further from so dangerous a neighbourhood. There is a little cabin boy on board, and Mr. J——— has brought with him a black terrier; and these two at first sight swore to each other an eternal friendship, in the true German style. It is the boy’s first voyage, and he is excessively sea-sick; so he has been obliged to creep into his hammock, and his friend, the little black terrier, has crept into the hammock with him. A boat came from the shore this evening, and reported that several vessels have been dismasted, lost their anchors, and injured in various ways. A brig, which was obliged to make for Ramsgate, missed the pier, and was dashed to pieces completely; the crew, however, were saved, all except the pilot; who, although he was brought on shore alive, what between bruises, drowning, and fright, had suffered so much, that he died two hours afterwards. The weather has now again become calm; but it is still full west.

NOVEMBER 14. (TUESDAY.)

THE HOURS.

Ne’er were the zephyrs known disclosing

More sweets, than when in Tempe’s shades

They waved the lilies, where, reposing,

Sat four and twenty lovely maids.

Those lovely maids were called “the Hours,”

The charge of Virtue’s flock they kept;

And each in turn employ’d her powers

To guard it, while her sisters slept.

False Love, how simple souls thou cheatest!

In myrtle bower, that traitor near

Long watch’d an Hour, the softest, sweetest!

The evening Hour, to shepherds dear. *

In tones so bland he praised her beauty,

Such melting airs his pipe could play,

The thoughtless Hour forgot her duty,

And fled in Love’s embrace away.

Meanwhile the fold was left unguarded—

The wolf broke in—the lambs were slain:

And now from Virtue’s train discarded,

With tears her sisters speak their pain.

Time flies, and still they weep; for never

The fugitive can time restore:

An Hour once fled, has fled for ever,

And all the rest shall smile no more!

* L’heure du berger.

NOVEMBER 15.

The wind altered sufficiently to allow us to escape from the Downs; and at dusk we were off Beachy Head. This morning, the steward left the trap-door of the store-hole open; of course, I immediately contrived to step into it, and was on the point of being precipitated to the bottom, among innumerable boxes of grocery, bags of biscuit, and porter barrels;—where a broken limb was the least that I could expect. Luckily, I fell across the corner of the trap, and managed to support myself, till I could effect my escape with a bruised knee, and the loss of a few inches of skin from my left arm.

NOVEMBER 16.

Off the Isle of Wight.

NOVEMBER 17.

Off the St. Alban’s Head. Sick to death! My temples throbbing, my head burning, my limbs freezing, my mouth all fever, my stomach all nausea, my mind all disgust.

NOVEMBER 18.

Off the Lizard, the last point of England.

NOVEMBER 19. (SUNDAY.)

At one this morning, a violent gust of wind came on; and, at the rate of ten miles an hour, carried us through the Chops of the Channel, formed by the Scilly Rocks and the Isle of Ushant. But I thought, that the advance was dearly purchased by the terrible night which the storm made us pass. The wind roaring, the waves dashing against the stern, till at last they beat in the quarter gallery; the ship, too, rolling from side to side, as if every moment she were going to roll over and over! Mr. J——— was heaved off one of the sofas, and rolled along, till he was stopped by the table. He then took his seat upon the floor, as the more secure position; and, half an hour afterwards, another heave chucked him back again upon the sofa. The captain snuffed out one of the candles, and both being tied to the table, could not relight it with the other: so the steward came to do it; when a sudden heel of the ship made him extinguish the second candle, tumbled him upon the sofa on which I was lying, and made the candle which he had brought with him fly out of the candlestick, through a cabin window at his elbow; and thus we were all left in the dark. Then the intolerable noise! the cracking of bulkheads! the sawing of ropes! the screeching of the tiller! the trampling of the sailors! the clattering of the crockery! Every thing above deck and below deck, all in motion at once! Chairs, writing-desks, books, boxes, bundles, fire-irons and fenders, flying to one end of the room; and the next moment (as if they had made a mistake) flying back again to the other with the same hurry and confusion! “Confusion worse confounded!” Of all the inconveniences attached to a vessel, the incessant noise appears to me the most insupportable! As to our live stock, they seem to have made up their minds on the subject, and say with one of Ariosto’s knights (when he was cloven from the head to the chine), “or corvien morire” Our fowls and ducks are screaming and quacking their last by dozens; and by Tuesday morning, it is supposed that we shall not have an animal alive in the ship, except the black terrier—and my friend the squeaking pig, whose vocal powers are still audible, maugre the storm and the sailors, and who (I verily believe) only continues to survive out of spite, because he can join in the general chorus, and help to increase the number of abominable sounds.

We are now tossing about in the Bay of Biscay: I shall remember it as long as I live. The “beef-eater’s front” could never have “beamed more terrible” upon Don Ferolo Whiskerandos, “in Biscay’s Bay, when he took him prisoner,” than Biscay’s Bay itself will appear to me the next time that I approach it.

NOVEMBER 20.

Our live stock has received an increase; our fowls and ducks are dead to be sure, but a lark flew on board this morning, blown (as is supposed) from the coast of France. In five minutes it appeared to be quite at home, eat very readily whatever was given it, and hopped about the deck without fear of the sailors, or the more formidable black terrier, with all the ease and assurance imaginable.

I dare say, it was blown from the coast of France!

NOVEMBER 21.

The weather continues intolerable. Boisterous waves running mountains high, with no wind, or a foul one. Dead calms by day, which prevent our making any progress; and violent storms by night, which prevent our getting any sleep.

Every thing is in a state of perpetual motion. “Nulla quies intus (nor outus indeed for the matter of that), nullâque silentia parte” We drink our tea exactly as Tantalus did in the infernal regions; we keep bobbing at the basin for half an hour together without being able to get a drop; and certainly nobody on ship-board can doubt the truth of the proverb, “Many things fall out between the cup and the lip.”

NOVEMBER 23.

PANDORA’S BOX. (Iliad A.)

Prometheus once (in Tooke the tale you’ll see)

In one vast box enclosed all human evils;

But curious Woman needs the inside would see,

And out came twenty thousand million devils.

The story’s spoil’d, and Tooke should well be chid;

The fact, sir, happen’d thus, and I’ve no doubt of it:

’Twas not that Woman raised the coffer’s lid,

But when the lid was raised, Woman popp’d out of it.

“But Hope remain’d”—true, sir, she did; but still

All saw of what Miss Hope gave intimation;

Her right hand grasp’d an undertaker’s bill,

Her left conceal’d a deed of separation.

N. B. I was most horribly sea-sick when I took this view of the subject. Besides, grapes on shipboard, in general, are remarkably sour.

NOVEMBER 24.

“Manibus date lilia plenis;

Purpureos spargam flores!”

The squeaking pig was killed this morning.

NOVEMBER 25.

Letters were sent to England by a small vessel bound for Plymouth, and laden with oranges from St. Michael’s, one of the Azores.

NOVEMBER 26.

A complete and most violent storm, from twelve at night till seven the next morning. The fore-top-sail, though only put up for the first time yesterday, was rent from top to bottom; and several of the other sails are torn to pieces. The perpetual tempestuous weather which we have experienced has so shaken the planks of the vessel, that the sea enters at all quarters. About one o’clock in the morning I was saluted by a stream of water, which poured down exactly upon my face, and obliged me to shift my lodgings. The carpenter had been made aware that there was a leak in my cabin, and ordered to caulk the seams; but, I suppose, he thought that during only a two months’ voyage, the rain might very possibly never find out the hole, and that it would be quite time enough to apply the remedy when I should have felt the inconvenience. The best is, that the carpenter happening to be at work in the next cabin when the water came down upon me, I desired him to call my servant, in order that I might get up, on account of the leak; on which he told me “that the leak could not be helped;” grumbled a good deal at calling up the servant; and seemed to think me not a little unreasonable for not lying quietly, and suffering myself to be pumped upon by this shower-bath of his own providing.

But if the water gets into the ship, on the other hand, last night the poor old steward was very near getting out of it. In the thick of the storm he was carrying some grog to the mate, when a gun, which drove against him, threw him off his balance, and he was just passing through one of the port-holes, when, luckily, he caught hold of a rope, and saved himself. A screech-owl flew on board this morning: I am sure we have no need of birds of ill omen; I could supply the place of a whole aviary of them myself.

NOVEMBER 28.

Reading Don Quixote this morning, I was greatly pleased with an instance of the hero’s politeness, which had never struck me before. The Princess Micomicona having fallen into a most egregious blunder, he never so much as hints a suspicion of her not having acted precisely as she has stated, but only begs to know her reasons for taking a step so extraordinary. “But pray, madam,” says he, “why did your ladyship land at Ossuna, seeing that it is not a seaport town?”

I was also much charmed with an instance of conjugal affection, in the same work. Sancho being just returned home, after a long absence, the first thing which his wife, Teresa, asks about, is the welfare of the ass. “I have brought him back,” answers Sancho, “and in much better health and condition than I am in myself.” “The Lord be praised,” said Teresa, “for this his great mercy to me!”

NOVEMBER 29.

The wind continues contrary, and the weather is as disagreeable and perverse as it can well be; indeed, I understand that in these latitudes nothing can be expected but heavy gales or dead calms, which makes them particularly pleasant for sailing, especially as the calms are by far the most disagreeable of the two: the wind steadies the ship; but when she creeps as slowly as she does at present (scarcely going a mile in four hours), she feels the whole effect of the sea breaking against her, and rolls backwards and forwards with every billow as it rises and falls. In the mean while, every thing seems to be in a state of the most active motion, except the ship; while we are carrying a spoonful of soup to our mouths, the remainder takes the “glorious golden opportunity” to empty itself into our laps, and the glasses and salt-cellars carry on a perpetual domestic warfare during the whole time of dinner, like the Guelphs and the Ghibellines. Nothing is so common as to see a roast goose suddenly jump out of its dish in the middle of dinner, and make a frisk from one end of the table to the other; and we are quite in the habit of laying wagers which of the two boiled fowls will arrive at the bottom first.

N.B. To-day the fowl without the liver wing was the favourite, but the knowing ones were taken in; the uncarved one carried it hollow.

NOVEMBER 30

“Do those I love e’er think on me?”

How oft that painful doubt will start,

To blight the roseate smile of glee,

And cloud the brow, and sink the heart!

No more can I, estranged from home,

Their pleasures share, nor soothe their moans

To them I’m dead as were the foam

Now breaking o’er my whitening bones.

And doubtless now with newer friends,

The tide of life content they stem;

Nor on the sailor think, who bends

Full many an anxious thought on them.

Should that reflection cause me pain?

No ease for mine their grief could bring;

Enough if, when we meet again,

Their answering hearts to greet me spring.

Enough, if no dull joyless eye

Give signs of kindness quite forgot;

Nor heartless question, cold reply,

Speak—“all is past; I love you not.”

Too much has heav’n ordain’d of woe,

Too much of groans on earth abounds,

For me to wish one tear to flow

Which brings no balm for sorrow’s wounds.

Love’s moisten’d lid and Friendship’s sigh,

I could not see, I could not hear!

To think “they weep!” more fills mine eye,

And smarts the more each tender tear.

Then, if there be one heart so kind,

It mourns each hour the loss of me;

Shrinks, when it hears some gust of wind,

And sighs—“Perhaps a storm at sea!”

Oh! if there be an heart indeed,

Which beats for me, so sad, so true,

Swift to its aid, Oblivion, speed,

And bathe it with thy poppy’s dew;

My form in vapours to conceal,

From Pleasure’s wreath rich odours shake;

Nor let that heart one moment feel

Such pangs as force my own to ache.

Demon of Memory, cherish’d grief!

Oh, could I break thy wand in twain!

Oh, could I close thy magic leaf,

Till those I love are mine again!

DECEMBER 1. (FRIDAY.)

The captain to-day pointed oat to me a sailor-boy, who, about three years ago, was shaken from the mast-head, and fell through the scuttle into the hold; the distance was above eighty feet, yet the boy was taken up with only a few bruises.

DECEMBER 3. (SUNDAY.)

The wind during the last two days has been more favourable; and at nine this morning we were in the latitude of Madeira.

DECEMBER 5.

Sea Terms.—Ratlines, the rope ladders by which the sailors climb the shrouds; the companion, the cabin-head; reefs, the divisions by which the sails are contracted; stunsails, additional sails, spread for the purpose of catching all the wind possible; the fore-mast, main-mast, mizen-mast; fore, the head; aft, the stern; being pooped (the very sound of which tells one, that it must be something very terrible), having the stern beat in by the sea; to belay a rope, to fasten it.

DECEMBER 6.

I had no idea of the expense of building and preserving a ship: that in which I am at present cost £30,000 at its outset. Last year the repairs amounted to £14,000; and in a voyage to the East Indies they were more than £20,000. In its return last year from Jamaica it was on the very brink of shipwreck. A storm had driven it into Bantry Bay, and there was no other refuge from the winds than Bear Haven, whose entrance was narrow and difficult; however, a gentleman from Castletown came on board, and very obligingly offered to pilot the ship. He was one of the first people in the place, had been the owner of a vessel himself, was most thoroughly acquainted with every inch of the haven, &c. &c., and so on they went. There was but one sunken rock, and that about ten feet in diameter; the captain knew it, and warned his gentleman-pilot to keep a little more to the eastward. “My dear friend,” answered the Irishman, “now do just make yourself asy; I know well enough what we are about; we are as clear of the rock as if we were in the Red Sea, by Jasus;”—upon which the vessel struck upon the rock, and there she stuck. The captain fell to swearing and tearing his hair. “God damn you, sir! didn’t I tell you to keep to eastward? Dam’me, she’s on the rock!” “Oh! well, my dear, she’s now on the rock, and, in a few minutes, you know, why she’ll be off the rock: to be sure, I’d have taken my oath that the rock was two hundred and fifty feet on the other side of her, but——“—“Two hundred and fifty feet! why, the channel is not two hundred and fifty feet wide itself! and as to getting her off, bumping against this rock, it can only be with a great hole in her side.”—“Poh! now, bother, my dear! why sure——“—“Leave the ship, sir; dam’me, sir, get out of my ship this moment!” Instead of which, with the most smiling and obliging air in the world, the Irishman turned to console the female passengers. “Make yourselves asy, ladies, pray make yourselves perfectly asy; but, upon my soul, I believe your captain’s mad; no danger in life! only make yourselves asy, I say; for the ship lies on the rock as safe and as quiet, by Jasus, as if she were lying on a mud bank!” Luckily the weather was so perfectly calm, that the ship having once touched the rock with her keel bumped no more. It was low water; she wanted but five inches to float her, and when the tide rose she drifted off, and with but little harm done. The gentleman-pilot then thought proper to return on shore, took a very polite leave of the lady-passengers, and departed with all the urbanity possible; only +thinking the captain the strangest person that he had ever met with; and wondering that any man of common sense could be put out of temper by such a trifle.

DECEMBER 7.

Yesterday we had the satisfaction of falling in with the trade wind, and now we are proceeding both rapidly and steadily. The change of climate is very perceptible; and the deep and beautiful blue which colours the sea is a certain intimation of our approach to the tropic. A few flying fish have made their appearance; and the spears are getting in order for the reception of their constant attendant, the dolphin. These spears have ropes affixed to them, and at one end of the pole are five barbs, at the other a heavy ball of lead: then, when the fish is speared, the striker lets the staff fall, on which down goes the lead into the sea, and up goes the dolphin into the air, who is in the utmost astonishment to find itself all of a sudden turned into a flying fish; so determines to cultivate the art of flying for the future, and promises itself a great many pleasant airings. The dolphin and the flying fish are beautifully coloured, and both are very good food, particularly the latter, which move in shoals like the herring, and are about the size of that fish. They are supposed to feed on spawn and sea animalculæ, and will not take the bait; but on the shores of Barbadoes, which they frequent in great multitudes, they are caught in wide nets, spread upon the surface of the sea; then, upon beating the waters around, the fish rise in clouds, and fly till, their fins getting dry, they fall down into the nets which have been spread to receive them. The dolphin is seldom above three feet long; the immense strength which he exerts in his struggles for liberty occasions the necessity of catching him in the way before described.

DECEMBER 8.

At three o’clock this afternoon we entered the tropic of Cancer; and if our wind continues tolerably favourable, we may expect to see Antigua on Sunday. On crossing the line, it was formerly usual for ships to receive a visit from an old gentleman and his wife, Mr. and Mrs. Cancer: the husband was, by profession, a barber; and, probably, the scullion, who insisted so peremptorily on shaving Sancho, at the duke’s castle, had served an apprenticeship to Mr. Cancer, for their mode of proceeding was much alike, and, indeed, very peculiar: the old gentleman always made a point of using a rusty iron hoop instead of a razor, tar for soap, and an empty beef-barrel was, in his opinion, the very best possible substitute for a basin; in consequence of which, instead of paying him for shaving them, people of taste were disposed to pay for not being shaved; and as Mrs. Cancer happened to be particularly partial to gin (when good), the gift of a few bottles was generally successful in rescuing the donor’s chin from the hands of her husband; however, to-day this venerable pair “peradventure were sleeping, or on a journey,” for we neither saw nor heard any thing about them.

DECEMBER 9.

When, after his victory of the 1st of June, Lord Howe again put to sea from Portsmouth, the number of women who were turned on shore out of the ships (wives, sisters, &c.) amounted to above thirty thousand!

DECEMBER 10. (Sunday.)

What triumph moves on the billows so blue?

In his car of pellucid pearl I view,

With glorious pomp, on the dancing tide,

The tropic Genius proudly ride.

The flying fish, who trail his car,

Dazzle the eye, as they shine from afar;

Twinkling their fins in the sun, and show

All the hues which adorn the showery bow.

Of dark sea-blue is the mantle he wears;

For a sceptre a plantain branch he bears;

Pearls his sable arms surround,

And his locks of wool with coral are crown’d.

Perpetual sunbeams round him stream;

His bronzed limbs shine with golden gleam;

The spicy spray from his wheels that showers,

Makes the sense ache with its odorous powers.

Myriads of monsters, who people the caves

Of ocean, attendant plough the waves;

Sharks and crocodiles bask in his blaze,

And whales spout the waters which dance in his rays.

And as onward floats that triumph gay,

The light sea-breezes around it play;

While at his royal feet lie bound

The Ouragans, hush’d in sleep profound.

Dark Genius, hear a stranger’s prayer,

Nor suffer those winds to ravage and tear

Jamaica’s savannas, and loose to fly,

Mingling the earth, and the sea, and the sky.

From thy locks on my harvest of sweets diffuse,

To swell my canes, refreshing dews;

And kindly breathe, with cooling powers,

Through my coffee walks and shaddock bowers.

Let not thy strange diseases prey

On my life; but scare from my couch away

The yellow Plague’s imps; and safe let me rest

From that dread black demon, who racks the breast:

Nor force my throbbing temples to know

Thy sunbeam’s sudden and maddening blow;

Nor bid thy day-flood blaze too bright

On nerves so fragile, and brain so light:

And let me, returning in safety, view

Thy triumph again on the ocean blue;

And in Britain I’ll oft with flowers entwine

The Tropic Sovereign’s ebony shrine!

Was it but fancy? did He not frown,

And in anger shake his coral crown?

Gorgeous and slow the pomp moves on!

Low sinks the sun—and all is gone!

“And pray now do you mean to say that you really saw all this fine show?” Oh, yes, really, “in my mind’s eye, Horatio,” as Shakspeare says; or, if you like it better in Greek—

[Greek line] Odyssey, A.

DECEMBER 11.

A dead centipes was found on the deck, supposed to have made its way on board, during the last voyage, among the logwood. This is not the only species of disagreeable passengers, who are in the habit of introducing themselves into homeward bound vessels without leave. While sleeping on deck last year, the Captain felt something run across his face; and, supposing it to be a cock-roach, he brushed off a scorpion; but not without its first biting him upon the cheek: the pain for about four hours was excessive; but although he did no more than wash the wound with spirits, he was perfectly well again in a couple of days.

DECEMBER 12.

Since we entered the tropic, the rains have been incessant, and most violent; but the wind was brisk and favourable, and we proceeded rapidly. Now we have lost the trade-wind, and move so slowly, that it might almost be called standing still. On the other hand, the weather is now perfectly delicious; the ship makes but little way, but she moves steadily: the sun is brilliant; the sky cloudless; the sea calm, and so smooth that it looks like one extended sheet of blue glass; an awning is stretched over the deck; although there is not wind enough to fill the canvass, there is sufficient to keep the air cool, and thus, even during the day, the weather is very pleasant; but the nights are quite heavenly, and so bright, that at ten o’clock yesterday evening little Jem Parsons (the cabin boy), and his friend the black terrier, came on deck, and sat themselves down on a gun-carriage, to read by the light of the moon. I looked at the boy’s book, (the terrier, I suppose, read over the other’s shoulder,) and found that it was “The Sorrows of Werter.” I asked who had lent him such a book, and whether it amused him? He said that it had been made a present to him, and so he had read it almost through, for he had got to Werter’s dying; though, to be sure, he did not understand it all, nor like very much what he understood; for he thought the man a great fool for killing himself for love. I told him I thought every man a great fool who killed himself for love or for any thing else: but had he no books but “The Sorrows of Werter?”—Oh dear, yes, he said, he had a great many more; he had got “The Adventures of a Louse,” which was a very curious book, indeed; and he had got besides “The Recess,” and “Valentine and Orson,” and “Ros-lin Castle,” and a book of Prayers, just like the Bible; but he could not but say that he liked “The Adventures of a Louse” the best of any of them.

DECEMBER 13.

We caught a dolphin, but not with the spear: he gorged a line which was fastened to the stern, and baited with salt pork; but being a very large and strong fish, his efforts to escape were so powerful, that it was feared that he would break the line, and a grainse (as the dolphin-spear is technically termed) was thrown at him: he was struck, and three of the prongs were buried in his side; yet, with a violent effort, he forced them out again, and threw the lance up into the air. I am not much used to take pleasure in the sight of animal suffering; but if Pythagoras himself had been present, and “of opinion that the soul of his grandam might haply inhabit” this dolphin, I think he must still have admired the force and agility displayed in his endeavours to escape. Imagination can picture nothing more beautiful than the colours of this fish: while covered by the waves he was entirely green; and as the water gave him a case of transparent crystal, he really looked like one solid piece of living emerald; when he sprang into the air, or swam fatigued upon the surface, his fins alone preserved their green, and the rest of his body appeared to be of the brightest yellow, his scales shining like gold wherever they caught the sun; while the blood which, as long as he remained in the sea, continued to spout in great quantities, forced its way upwards through the water, like a wreath of crimson smoke, and then dispersed itself in separate globules among the spray. From the great loss of blood, his colours soon became paler; but when he was at length safely landed on deck, and beating himself to death against the flooring, agony renewed all the lustre of his tints: his fins were still green and his body golden, except his back, which was olive, shot with bright deep blue; his head and belly became silvery, and the spots with which the latter was mottled changed, with incessant rapidity, from deep olive to the most beautiful azure. Gradually his brilliant tints disappeared: they were succeeded by one uniform shade of slate-colour; and when he was quite dead, he exhibited nothing but dirty brown and dull dead white. As soon as all was over with him, the first thing done was to convert one of his fins into the resemblance of a flying fish, for the purpose of decoying other dolphins; and the second, to order some of the present gentleman to be got ready for dinner. He measured above four feet and a half.

DECEMBER 14.

At noon to-day, we found ourselves in the latitude of Jamaica. We were promised the sight of Antigua on Sunday next, but that is now quite out of the question. We made but eight miles in the whole of yesterday; and as Jamaica is still at the distance of eighteen hundred miles, at this rate of proceeding we may expect to reach it about eight months hence. The sky this evening presented us with quite a new phenomenon, a rose-coloured moon: she is to be at her full to-morrow; and this afternoon, about half-past four, she rose like a disk of silver, perfectly white and colourless; but, as she was exactly opposite to the sun at the time of his setting, the reflection of his rays spread a kind of pale blush over her orb, which produced an effect as beautiful as singular. Indeed, the size and inconceivable brilliance of the sun, the clearness of the atmosphere, which had assumed a faint greenish hue, and was entirely without a cloud, the smoothness of the ocean, and the aforesaid rose-coloured moon, altogether rendered this sunset the most magical in effect that I ever beheld; and it was with great reluctance that I was called away from admiring it, to ascertain whether the merits of our new acquaintance, the dolphin, extended any further than his skin. Part of him, which was boiled for yesterday’s dinner, was rather coarse and dry, and might have been mistaken for indifferent haddock. But his having been steeped in brine, and then broiled with a good deal of pepper and salt, had improved him wonderfully; and to-day I thought him as good as any other fish.

Our wind is like Lady Townley’s separate allowance: “that little has been made less;” or, rather, it has dwindled away to nothing. We are now so absolutely becalmed, that I begin seriously to suspect all the crew of being Phæacians; and that at this identical moment Neptune is amusing himself by making the ship take root in the ocean; a trick which he played once before to a vessel (they say) in the days of Ulysses. I have got some locust plants on board in pots: if we continue to sail as slowly as we have done for the last week, before we reach Jamaica my plants will be forest trees, little Jem, the cabin-boy, will have been obliged to shave, and the black terrier will have died of old age long ago. Great numbers of porpoises were playing about to-day, and tumbling under the ship’s very nose. When in their gambols they allow themselves to be seen above the surface, they are of a dirty blackish brown, and as ugly as heart can wish; but in the waves they acquire a fine sea-green cast, and their spouting up water in the sunbeams is extremely ornamental.

THE HELMSMAN.

Hark! the bell 1 it sounds midnight!—all hail, thou new

heav’n!

How soft sleep the stars on their bosom of night!

While o’er the full moon, as they gently are driven,

Slowly floating the clouds bathe their fleeces in light.

The warm feeble breeze scarcely ripples the ocean,

And all seems so hush’d, all so happy to feel!

So smooth glides the bark, I perceive not her motion,

While low sings the sailor who watches the wheel.

That sailor I’ve noted—his cheek, fresh and blooming

With health, scarcely yet twenty springs can have

seen;

His looks they are lofty, but never presuming,

His limbs strong, but light, and undaunted his mien.

Frank and clear is his brow, yet a thoughtful expression,

Half tender, half mournful, oft shadows his eye;

And murmurs escape him, which make the confession,

If not check’d by a hem, they had swell’d to a sigh.

His song is not pour’d to beguile the lone hour,

When in-watch on deck ’tis his duty to keep;

Nor of painful reflection to weaken the power,

Nor chase from his eyelids the pinions of sleep.

Tis so sad...‘tis so sweet... and some tones come so

swelling,

So right from the heart, and so pure to the ear;—

That sure at this moment his thoughts must be dwelling

On one who is absent, most kind and most dear.

Perhaps on a mother his mind loves to linger,

Whose wants to relieve, the rough seas hath he

cross’d;

Who kiss’d him at parting, and vow’d he could bring her

No jewel so dear as the one she then lost!

No, no! ’tis a sweetheart, his soul’s cherish’d treasure,

Those full melting notes... hark! he breathes them

again!

So mournful, and yet they’re prolong’d with such plea

sure........

Oh, nothing but love could have prompted the strain.

Yet, whate’er be the cause of thy sadness, young seaman,

That the weight be soon lighten’d, I send up my vow;

From the stings of remorse, I’ll be sworn, thou’rt a

freeman,

No guilt ever ruffled the smooth of that brow!

That sigh which you breath’d sprang from pensive

affection;

That song, though so plaintive, sheds balm on the

heart;

And the pain which you feel at each fond recollection,

Is worth all the pleasures that vice could impart.

Oh, still may the scenes of your life, like the present,

Shine bright to the eye, and speak calm to the breast;

May each wave flow as gentle, each breeze play as

pleasant,

And warm as the clime prove the friends you love best!

And may she, who now dictates that ballad so tender,

Diffuse o’er your days the heart’s solace and ease,

As yon lovely moon, with a gleam of mild splendour,

Pure, tranquil, and bright, over-silvers the seas!

DECEMBER 16.

What little wind there is blows so perversely, that we have been obliged to alter our course; and instead of Antigua, we are now told that the Summer Islands (Shakspeare’s “still vexed Bermoothes”) are the first land that we must expect to see.

I am greatly disappointed at finding such a scarcity of monsters; I had flattered myself, that as soon as we should enter the Atlantic Ocean, or at least the tropic, we should have seen whole shoals of sharks, whales, and dolphins wandering about as plenty as sheep upon the South Downs: instead of which, a brace of dolphins, and a few flying fish and porpoises, are the only inhabitants of the ocean who have as yet taken the trouble of paying us the common civility of a visit. However, I am promised, that as soon as we approach the islands, I shall have as many sharks as heart can wish.

As I am particularly fond of proofs of conjugal attachment between animals (in the human species they are so universal that I set no store by them), an instance of that kind which the captain related to me this morning gave me great pleasure. While lying in Black River harbour, Jamaica, two sharks were frequently seen playing about the ship; at length the female was killed, and the desolation of the male was excessive:—

“Che faro senz’ Eurydice?”

What he did without her remains a secret, but what he did with her was clear enough; for scarce was the breath out of his Eurydice’s body, when he stuck his teeth in her, and began to eat her up with all possible expedition. Even the sailors felt their sensibility excited by so peculiar a mark of posthumous attachment; and to enable him to perform this melancholy duty the more easily, they offered to be his carvers, lowered their boat, and proceeded to chop his better half in pieces with their hatchets; while the widower opened his jaws as wide as possible, and gulped down pounds upon pounds of the dear departed as fast as they were thrown to him, with the greatest delight and all the avidity imaginable. I make no doubt that all the while he was eating, he was thoroughly persuaded that every morsel which went into his stomach would make its way to his heart directly! “She was perfectly consistent,” he said to himself; “she was excellent through life, and really she’s extremely good now she’s dead!” and then, “unable to conceal his pain,”

“He sigh’d and swallow’d, and sigh’d and swallow’d,

And sigh’d and swallow’d again.”

I doubt, whether the annals of Hymen can produce a similar instance of post-obitual affection. Certainly Calderon’s “Amor despues de la Muerte” has nothing that is worthy to be compared to it; nor do I recollect in history any fact at all resembling it, except perhaps a circumstance which is recorded respecting Cambletes, King of Lydia, a monarch equally remarkable for his voracity and uxoriousness; and who, being one night completely overpowered by sleep, and at the same time violently tormented by hunger, eat up his queen without being conscious of it, and was mightily astonished, the next morning, to wake with her hand in his mouth, the only bit that was left of her. But then, Cambletes was quite unconscious what he was doing; whereas, the shark’s mark of attachment was evidently intentional. It may, however, be doubted, from the voracity with which he eat, whether his conduct on this occasion was not as much influenced by the sentiment of hunger as of love; and if he were absolutely on the point of starving, Tasso might have applied to this couple, with equal truth, although with somewhat a different meaning, what he says of his “Amanti e Sposi;”—

——“Pende

D’ un fato sol e l’ una e l’ altra vita

for if Madam Shark had not died first, Monsieur must have died himself for want of a dinner.

DECEMBER 17. (Sunday.)

On this day, from a sense of propriety no doubt, as well as from having nothing else to do, all the crew in the morning betook themselves to their studies. The carpenter was very seriously spelling a comedy; Edward was engaged with “The Six Princesses of Babylon;” a third was amusing himself with a tract “On the Management of Bees;” another had borrowed the cabin-boy’s “Sorrows of Werter,” and was reading it aloud to a large circle—some whistling—and others yawning; and Werter’s abrupt transitions, and exclamations, and raptures, and refinements, read in the same loud monotonous tone, and without the slightest respect paid to stops, had the oddest effect possible. “She did not look at me; I thought my heart would burst; the coach drove off; she looked out of the window; was that look meant for me? yes it was; perhaps it might be; do not tell me that it was not meant for me. Oh, my friend, my friend, am I not a fool, a madman?” (This part is rather stupid, or so, you see, but no matter for that; where was I? oh!) “I am now sure, Charlotte loves me: I prest my hand on my heart; I said ‘Klopstock;’ yes, Charlotte loves me; what! does Charlotte love me? oh, rapturous thought! my brain turns round:—Immortal powers!—how!—what!—oh, my friend, my friend,” &c. &c. &c. I was surprised to find that (except Edward’s Fairy Tale) none of them were reading works that were at all likely to amuse them (Smollett or Fielding, for instance), or any which might interest them as relating to their profession, such as voyages and travels; much less any which had the slightest reference to the particular day. However, as most of them were reading what they could not possibly understand, they might mistake them for books of devotion, for any thing they knew to the contrary; or, perhaps, they might have so much reverence for all books in print, as to think that, provided they did but read something, it was doing a good work, and it did not much matter what. So one of Congreve’s fine ladies swears Mrs. Mincing, the waiting maid, to secrecy, “upon an odd volume of Messalina’s Poems.” Sir Dudley North, too, informs us, (or is it his brother Roger? but I mean the Turkey merchant: ):—that at Constantinople the respect for printed books is so great, that when people are sick, they fancy that they can be read into health again; and if the Koran should not be in the way, they will make a shift with a few verses of the Bible, or a chapter or two of the Talmud, or of any other book that comes first to hand, rather than not read something. I think Sir Dudley says, that he himself cured an old Turk of the toothache, by administering a few pages of “Ovid’s Metamorphoses;” and in an old receipt-book, we are directed for the cure of a double tertian fever, “to drink plentifully of cock-broth, and sleep with the Second Book of the Iliad under the pillow.” If, instead of sleeping with it under the pillow, the doctor had desired us to read the Second Book of the Iliad in order that we might sleep, I should have had some faith in his prescription myself.

DECEMBER 19.

During these last two days nothing very extraordinary, or of sufficient importance to deserve its being handed down to the latest posterity, has occurred; except that this morning a swinging rope knocked my hat into the sea, and away it sailed upon a voyage of discovery, like poor La Perouse, to return no more, I suppose; unless, indeed,—like Polycrates, the fortunate tyrant of Samos, who threw his favourite ring into the ocean, and found it again in the stomach of the first fish that was served up at his table,—I should have the good luck (but I by no means reckon upon it) to catch a dolphin with my hat upon his head: as to a porpoise, he never could squeeze his great numskull into it; but our dolphin of last week was much about my own size, and I dare say such another would find my hat fit him to a miracle, and look very well in it.

DECEMBER 20.

The weather is so excessively close and sultry, that it would be allowed to be too hot to be pleasant, even by that perfect model for all future lords of the bedchamber, who was never known to speak a word, except in praise, of any thing living or dead, through the whole course of his life: but, at last, one day he met with an accident—he happened to die; and the next day he met with another accident—he happened to be damned: and immediately upon his arrival in the infernal regions, the Devil (who was determined to be as well bred as the other could be for his ears,) came to pay his compliments to the new-comer, and very obligingly expressed his concern that his lordship was not likely to feel satisfied with his new abode; for that he must certainly find hell very hot and disagreeable. “Oh, dear, no!” exclaimed the Lord of the Bedchamber, “not at all disagreeable, by any manner of means, Mr. Devil, upon my word and honour! Rather warm, to be sure.” In point of heat there is no difference between the days and the nights; or if there is any, it is that the nights are rather the hottest of the two. The lightning is incessant, and it does not show itself forked or in flashes, but in wide sheets of mild blue light, which spread themselves at once over the sky and sea; and, for the moment which they last, make all the objects around as distinct as in daylight. The moon now does not rise till near ten o’clock, and during her absence the size and brilliancy of the stars are admirable. In England they always seemed to me (to borrow a phrase of Shakspeare’s, which, in truth, is not worth borrowing,) to “peep through the blanket of the dark;” but here the heavens appear to be studded with them on the outside, as if they were chased with so many jewels: it is really Milton’s “firmament of living sapphires;” and what with the lightning, the stars, and the quantity of floating lights which just gleamed round the ship every moment, and then were gone again, to-night the sky had an effect so beautiful, that when at length the moon thought proper to show her great red drunken face, I thought that we did much better without her.

The above-mentioned floating lights are a kind of sea-meteors, which, as I am told, are produced by the concussion of the waves, while eddying in whirlpools round the rudder; but still I saw them rise sometimes at so great a distance from the ship, and there appeared to be something so like Will in the direction of their course,—sometimes hurrying on, sometimes gliding along quite slowly; now stopping and remaining motionless for a minute or two, and then hurrying on again,—that I could not be convinced of their not being Medusæ, or some species or other of phosphoric animal: but whatever be the cause of this appearance, the effect is singularly beautiful. As to air, we have not enough to bless ourselves with. I had been led to believe, that when once we should have fallen in with the trade winds, from that moment we should sail into our destined port as rapidly and as directly as Truffaldino travels in Gozzi’s farce; when, having occasion to go from Asia to Europe, and being very much pressed for time, he persuades a conjuror of his acquaintance to lend him a devil, with a great pair of bellows, the nozzle of which being directed right against his stern, away goes the traveller before the stream of wind, with the devil after him, and the infernal bellows never cease from working till they have blown him out of one quarter of the globe into another: but our trade winds must “hide their diminished heads” before Truffaldino’s bellows. It seems that like the Moors, “in Africa the torrid,” they are “of temper somewhat mulish;” for, although, to be sure, when they do blow, they will only blow in one certain direction, yet very often they will not blow at all; which has been our case for the last week: indeed, they seem to be but a queerish kind of a concern at best. About three years ago a fleet of merchantmen was becalmed near St. Vincent’s: in a few days after their arrival, there happened a violent eruption of a volcano in that island, nor was it long before a favourable breeze sprang up. Unluckily, one of the ships had anchored rather nearer to the shore than the others, and was at the distance of about one hundred and fifty yards from the stream of the trade wind; nor could any possible efforts of the crew, by tacking, by towing, or otherwise, ever enable the vessel to conquer that one hundred and fifty yards: there she remained, as completely becalmed as if there were not such a thing as a breath of wind in the universe; and on the one hand she had the mortification to see the rest of the merchantmen, with their convoy (for it was in the very heat of the war), sail away with all their canvass spread and swelling; while, on the other hand, the sailors had the comfortable possibility of being suffocated every moment by the clouds of ashes which continued to fall on their deck every moment, from the burning volcano, although they were not nearer to St. Vincent’s than eight or nine miles; indeed that distance went for nothing, as ashes fell upon vessels that were out at sea at least five hundred miles; and Barbadoes being to windward of the volcano, such immense quantities of its contents were carried to that island as almost covered the fields; and destroying vegetation completely wherever they fell, did inconceivable damage, while that which St. Vincent’s itself experienced was but trifling in proportion.

Our captain is quite out of patience with the tortoise pace of our progress; for my part I care very little about it. Whether we have sailed slowly or rapidly, when a day is once over, I am just as much nearer advanced towards April, the time fixed for my return to England; and, what is of much more consequence, whether we have sailed slowly or rapidly, when a day is once over, I am just as much nearer advanced towards “that bourne,” to reach which, peaceably and harmlessly, is the only business of life, and towards which the whole of our existence forms but one continued journey.

DECEMBER 21.

We succeeded in catching another dolphin today; but he had not a hat on; however, I just asked him whether he happened to have seen mine, but to little purpose; for I found that he could tell me nothing at all about it; so, instead of bothering the poor animal with any more questions, we eat him.

DECEMBER 22.

About three years ago the Captain had the ill luck to be captured by a French frigate. As she had already made prizes of two other merchantmen, it was determined to sink his ship; which, after removing the crew and every thing in her that was valuable, was effected by firing her own guns down the hatchways. It was near three hours before she filled, then down she went with a single plunge, head foremost, with all her sails set and colours flying. This display of the ship’s magnificence in her last moments reminded me of Mary Queen of Scots, arraying herself in her richest robes that she might go to the scaffold. If Yorick had fallen in with this anecdote in the course of his journey, the situation of the Captain, standing on the enemy’s deck, and seeing his “brave vessel” in full and gallant trim, possessing all the abilities for a long existence, yet abandoned by every one, and sinking from the effect of her own shot, might have furnished him with a companion for his old commercial Marquis, lamenting over the rust of his newly recovered sword.

DECEMBER 23.

THE DOLPHIN.

Does then the insatiate sea relent?

And hath he back those treasures sent,

His stormy rage devoured?

All starred with gems the billows bound,

And emeralds, jacinths, sapphires round

The bark in spray are showered.

No, no! ’t is there the Dolphin plays;

His scales, enriched with sunny rays,

Celestial tints unfold;

And as he darts, the waters blue

Are streaked with gleams of many a hue,

Green, orange, purple, gold!

And brighter still will shine your skin,

Poor fish, more dazzling play each fin,

On deck when dying cast;

Like good men, who, expiring, bless

The Power that calls them, all confess

Your brightest hour your last.

And now the Spearman watchful stands!

The five-pronged grainse, which arms his hands,

Your scales is doomed to gore;

The lead will sink, and soon on high,

Borne from the deep, perforce you’ll fly,

Nor e’er regain it more.

Weep, Beauty, weep! those vivid dyes,

Those splendours, but the harpooner’s eyes

To strike his victim call!

Ambition, mark the Dolphin’s close—

To dangerous heights he only rose

To find the heavier fall!

Mark, too, ye witty, rich, and gay,

How quick those sportive fins could play,

How gay, how rich was he!

He moves no more—he’s cold to touch—

He’s dull—dark—dead! The Dolphin’s such,

And such we all must be!

There is a technical fault in the above lines: the grainse, or dolphin-spear, has five barbs; but the harpooner never uses a lance with more than a single point. However, the word was so agreeable to my ear, that I could not find in my heart to leave it out.

DECEMBER 24. (Sunday.)

At length we have crawled into the Caribbean Sea. I was told that we were not to expect to see land to-day; but on shipboard our not seeing a thing to-day by no means implies that we shall not see it before to-morrow; for the nautical day is supposed to conclude at noon, when the solar observation is taken; and, therefore, the making land to-day, or not, very often depends upon our making it before twelve o’clock, or after it. This was the case in the present instance; for noon was scarcely passed when we saw Descada (a small island totally unprovided with water, and whose only produce consists in a little cotton), Guadaloupe, and Marie Galante, though the latter was at so great a distance as to be scarcely visible. At sunset Antigua was in sight.

DECEMBER 25.

The sun rose upon Montserrat and Nevis, with the Rodondo rock between them, “apricis natio gratissima mergis,—” for it is perpetually covered with innumerable flocks of gulls, boobies, pelicans, and other sea birds. Then came St. Christopher’s and St. Eustatia; and in the course of the afternoon we passed over the Aves bank, a collection of sand, rock, and mud, extending about two hundred miles, and terminated at each end by a small island: one of them inhabited by a few fishermen, the other only by sea birds. Of all the Atlantic isles the soil of St. Christopher’s is by some supposed to be the richest, the land frequently producing three hogsheads an acre. I rather think that this was the first island discovered by Columbus, and that it took its name from his patron-saint. Montserrat is so rocky, and the roads so steep and difficult, that the sugar is obliged to be brought down in bags upon the backs of mules, and not put into casks, till its arrival on the sea shore.

The weather is now quite delicious; there is just wind enough to send us forward and keep the air cool: the sun is brilliant without being overpowering; the swell of the waves is scarcely perceptible; and the ship moves along so steadily, that the deck affords almost as firm footing as if we were walking on land. One would think that Belinda had been smiling on the Caribbean Sea, as she once before did on the Thames, and had “made all the world look gay.” During the night we passed Santa Cruz, an island which, from the perfection to which its cultivation has been carried, is called “the Garden of the West Indies.”

DECEMBER 28.

Having left Porto Rico behind us, at noon today we passed the insulated rock of Alcavella, lying about six miles from St. Domingo, which is now in sight. As this part of the Caribbean Sea is much infested by pirates from the Caraccas, all our muskets have been put in repair, and to-day the guns were loaded, of which we mount eight; but as one of them, during the last voyage, went overboard in a gale of wind, its place has been supplied by a Quaker, i. e. a sham gun of wood, so called, I suppose, because it would not fight if it were called upon. These pirate-vessels are small schooners, armed with a single twenty-four pounder, which moves upon a swivel, and their crew is composed of negroes and outlaws of all nations, their numbers generally running from one hundred to one hundred and fifty men. To-day, for the first time, I saw some flying fish: we have also been visited by several men-of-war birds and tropic birds; the latter is a species of gull, perfectly white, and distinguished by a single very long feather in its tail: its nautical name is “the boatswain.”

As we sail along, the air is absolutely loaded with “Sabean odours from the spicy shores” of St. Domingo, which we were still coasting at sunset.

DECEMBER 30.

At day-break Jamaica was in sight, or rather it would have been in sight, only that we could not see it. The weather was so gloomy, and the wind and rain were so violent, that we might have said to the Captain, as one of the two Punches who went into the ark is reported to have said to the patriarch, during the deluge, “Hazy weather, Master Noah.”—I remember my good friend, Walter Scott, asserts, that at the death of a poet the groans and tears of his heroes and heroines swell the blast and increase the river; perhaps something of the same kind takes place at the arrival of a West India proprietor from Europe, and all this rain and wind proceed from the eyes and lungs of my agents and overseers, who, for the last twenty years, have been reigning in my dominions with despotic authority; but now

“Whose groans in roaring winds complain,

Whose tears of rage impel the rain;”

because, on the approach of the sovereign himself, they must evacuate the palace, and resign the deputed sceptre. “Hinc illæ lachrymæ!” this is the cause of our being soaked to the skin this morning. However, about noon the weather cleared up, and allowed us to verify, with our own eyes, that we had reached “the Land of Springs,” without having been invited by any Piccaroon vessel to “walk the plank” instead of the deck; which is a compliment very generally paid by those gentry, after they have taken the trouble of laying a plank over the side of a captured ship, in order that the passengers and the crew may walk overboard without any inconvenience.

We arrived at the east end of the island, passed Pedro Point and Starvegut Bay, and arrived before Black River Bay (our destined harbour) soon after two o’clock; but here we were obliged to come to a stand still: the channel is very dangerous, extremely narrow, and full of sunken rocks; so that it can only be entered by a vessel drawing so much water as ours with a particular wind, and when there is not any apprehension of a sudden squall. We were, therefore, obliged to drop anchor, and are now riding within a couple of miles of the shore, but with as utter an incapability of reaching it as if we were still at Gravesend. The north side of the island is said to be extremely beautiful and romantic; but the south, which we coasted to-day, is low, barren, and without any recommendation whatever. As yet I can only look at Jamaica as one does on a man who comes to pay money, and whom we are extremely well pleased to see, however little the fellow’s appearance may be in his favour.

We passed the whole of the day in vain endeavours to work ourselves into the bay. At one time, indeed, we got very near the shore, but the consequence was, that we were within an ace of striking upon a rock, and very much obliged to a sudden gust of wind, which, blowing right off shore, blew us out of the channel, and left us at night in a much more perilous situation than we had occupied the evening before, though even that had been by no means secure. At three o’clock, the other passengers went on shore in the jolly-boat, and proceeded to their destination; but as I was still more than thirty miles distant from my estate, I preferred waiting on board till the Captain should have moored his vessel in safety, and be at liberty to take me in his pinnace to Savannah la Mar, when I should find myself within a few miles of my own house.

In the course of the afternoon, one of the sailors took up a fish of a very singular shape and most brilliant colours, as it floated along upon the water. It seemed to be gasping, and lay with its belly upwards; it was supposed to have eaten something poisonous, as whenever it was touched it appeared to be full of life, and squirted the water in our faces with great spirit and dexterity. But no sooner was he suffered to remain quiet in the tub, than he turned upon his back and again was gasping. He had a large round transparent globule, intersected with red veins, under the belly, which some imagined to proceed from a rupture, and to be the occasion of his disease. But I could not discover any vestige of a wound; and the globule was quite solid to the touch; neither did the fish appear to be sensible when it was pressed upon. No one on board had ever seen this kind of fish till then; its name is the “Doctor Fish.”

A black pilot came on board yesterday, in a canoe hollowed out of the cotton-tree; and when it returned for him this morning, it brought us a water-melon. I never met with a worse article in my life; the pulp is of a faint greenish yellow, stained here and there with spots of moist red, so that it looks exactly as if the servant in slicing it had cut his finger, and suffered it to bleed over the fruit. Then the seeds, being of a dark purple, present the happiest imitation of drops of clotted gore; and altogether (prejudiced as I was by its appearance), when I had put a single bit into my mouth, it had such a kind of Shylocky taste of raw flesh about it (not that I recollect having ever eaten a bit of raw flesh itself), that I sent away my plate, and was perfectly satisfied as to the merits of the fruit.

1816.—JANUARY 1.

At length the ship has squeezed herself into this champagne bottle of a bay! Perhaps, the satisfaction attendant upon our having overcome the difficulty, added something to the illusion of its effect; but the beauty of the atmosphere, the dark purple mountains, the shores covered with mangroves of the liveliest green down to the very edge of the water, and the light-coloured houses with their lattices and piazzas completely embowered in trees, altogether made the scenery of the Bay wear a very picturesque appearance. And, to complete the charm, the sudden sounds of the drum and banjee, called our attention to a procession of the John-Canoe, which was proceeding to celebrate the opening of the new year at the town of Black River. The John-Canoe is a Merry-Andrew dressed in a striped doublet, and bearing upon his head a kind of pasteboard house-boat, filled with puppets, representing, some sailors, others soldiers, others again slaves at work on a plantation, &c. The negroes are allowed three days for holidays at Christmas, and also New-year’s day, which being the last is always reckoned by them as the festival of the greatest importance. It is for this day that they reserve their finest dresses, and lay their schemes for displaying their show and expense to the greatest advantage; and it is then that the John-Canoe is considered not merely as a person of material consequence, but one whose presence is absolutely indispensable. Nothing could look more gay than the procession which we now saw with its train of attendants, all dressed in white, and marching two by two (except when the file was broken here and there by a single horseman), and its band of negro music, and its scarlet flags fluttering about in the breeze, now disappearing behind a projecting clump of mangrove trees, and then again emerging into an open part of the road, as it wound along the shore towards the town of Black River.

——“Magno telluris amore

Egressi optatâ Troes potiuntur arena.”

I had determined not to go on shore, till I should land for good and all at Savannah la Mar. But although I could resist the “telluris amor,” there was no resisting John-Canoe; so, in defiance of a broiling afternoon’s sun, about four o’clock we left the vessel for the town.

It was, as I understand, formerly one of some magnitude; but it now consists only of a few houses, owing to a spark from a tobacco-pipe or a candle having lodged upon a mosquito-net during dry weather; and although the conflagration took place at mid-day, the whole town was reduced to ashes. The few streets—(I believe there were not above two, but those were wide and regular, and the houses looked very neat)—were now crowded with people, and it seemed to be allowed, upon all hands, that New-year’s day had never been celebrated there with more expense and festivity.

It seems that, many years ago, an Admiral of the Red was superseded on the Jamaica station by an Admiral of the Blue; and both of them gave balls at Kingston to the “Brown Girls;” for the fair sex elsewhere are called the “Brown Girls” in Jamaica. In consequence of these balls, all Kingston was divided into parties: from thence the division spread into other districts: and ever since, the whole island, at Christmas, is separated into the rival factions of the Blues and the Reds (the Red representing also the English, the Blue the Scotch), who contend for setting forth their processions with the greatest taste and magnificence. This year, several gentlemen in the neighbourhood of Black River had subscribed very largely towards the expenses of the show; and certainly it produced the gayest and most amusing scene that I ever witnessed, to which the mutual jealousy and pique of the two parties against each other contributed in no slight degree. The champions of the rival Roses,—the Guelphs and the Ghibellines,—none of them could exceed the scornful animosity and spirit of depreciation with which the Blues and the Reds of Black River examined the efforts at display of each other. The Blues had the advantage beyond a doubt; this a Red girl told us that she could not deny; but still, “though the Reds were beaten, she would not be a Blue girl for the whole universe!” On the other hand, Miss Edwards (the mistress of the hotel from whose window we saw the show), was rank Blue to the very tips of her fingers, and had, indeed, contributed one of her female slaves to sustain a very important character in the show; for when the Blue procession was ready to set forward, there was evidently a hitch, something was wanting; and there seemed to be no possibility of getting on without it—when suddenly we saw a tall woman dressed in mourning (being Miss Edwards herself) rush out of our hotel, dragging along by the hand a strange uncouth kind of a glittering tawdry figure, all feathers, and pitchfork, and painted pasteboard, who moved most reluctantly, and turned out to be no less a personage than Britannia herself, with a pasteboard shield covered with the arms of Great Britain, a trident in her hand, and a helmet made of pale blue silk and silver. The poor girl, it seems, was bashful at appearing in this conspicuous manner before so many spectators, and hung back when it came to the point. But her mistress had seized hold of her, and placed her by main force in her destined position. The music struck up; Miss Edwards gave the Goddess a great push forwards; the drumsticks and the elbows of the fiddlers attacked her in the rear; and on went Britannia willy-nilly!

The Blue girls called themselves “the Blue girls of Waterloo.” Their motto was the more patriotic; that of the Red was the more gallant:—“Britannia rules the day!” streamed upon the Blue flag; “Red girls for ever!” floated upon the Red. But, in point of taste and invention, the former carried it hollow. First marched Britannia; then came a band of music; then the flag; then the Blue King and Queen—the Queen splendidly dressed in white and silver (in scorn of the opposite party, her train was borne by a little girl in red); his Majesty wore a full British Admiral’s uniform, with a white satin sash, and a huge cocked hat with a gilt paper crown upon the top of it. These were immediately followed by “Nelson’s car,” being a kind of canoe decorated with blue and silver drapery, and with “Trafalgar” written on the front of it; and the procession was closed by a long train of Blue grandees (the women dressed in uniforms of white, with robes of blue muslin), all Princes and Princesses, Dukes and Duchesses, every mother’s child of them.

The Red girls were also dressed very gaily and prettily, but they had nothing in point of invention that could vie with Nelson’s Car and Britannia; and when the Red throne made its appearance, language cannot express the contempt with which our landlady eyed it. “It was neither one thing nor t’other,” Miss Edwards was of opinion. “Merely a few yards of calico stretched over some planks—and look, look, only look at it behind! you may see the bare boards! By way of a throne, indeed! Well, to be sure, Miss Edwards never saw a poorer thing in her life, that she must say!” And then she told me, that somebody had just snatched at a medal which Britannia wore round her neck, and had endeavoured to force it away. I asked her who had done so? “Oh, one of the Red party, of course!” The Red party was evidently Miss Edwards’s Mrs. Grundy. John-Canoe made no part of the procession; but he and his rival, John-Crayfish (a personage of whom I heard, but could not obtain a sight), seemed to act upon quite an independent interest, and go about from house to house, tumbling and playing antics to pick up money for themselves.

A play was now proposed to us, and, of course, accepted. Three men and a girl accordingly made their appearance; the men dressed like the tumblers at Astley’s, the lady very tastefully in white and silver, and all with their faces concealed by masks of thin blue silk; and they proceeded to perform the quarrel between Douglas and Glenalvon, and the fourth act of “The Fair Penitent.” They were all quite perfect, and had no need of a prompter. As to Lothario, he was by far the most comical dog that I ever saw in my life, and his dying scene exceeded all description; Mr. Coates himself might have taken hints from him! As soon as Lothario was fairly dead, and Calista had made her exit in distraction, they all began dancing reels like so many mad people, till they were obliged to make way for the Waterloo procession, who came to collect money for the next year’s festival; one of them singing, another dancing to the tune, while she presented her money-box to the spectators, and the rest of the Blue girls filling up the chorus. I cannot say much in praise of the black Catalani; but nothing could be more light, and playful, and graceful, than the extempore movements of the dancing girl. Indeed, through the whole day, I had been struck with the precision of their march, the ease and grace of their action, the elasticity of their step, and the lofty air with which they carried their heads—all, indeed, except poor Britannia, who hung down hers in the most ungoddess-like manner imaginable. The first song was the old Scotch air of “Logie of Buchan,” of which the girl sang one single stanza forty times over. But the second was in praise of the Hero of Heroes; so I gave the songstress a dollar to teach it to me, and drink the Duke’s health. It was not easy to make out what she said, but as well as I could understand them, the words ran as follows:—

“Come, rise up, our gentry,

And hear about Waterloo;

Ladies, take your spy-glass,

And attend to what we do;

For one and one makes two,

But one alone must be.

Then singee, singee Waterloo,

None so brave as he!”

—and then there came something about green and white flowers, and a Duchess, and a lily-white Pig, and going on board of a dashing man of war; but what they all had to do with the Duke, or with each other, I could not make even a guess. I was going to ask for an explanation, but suddenly half of them gave a shout loud enough “to fright the realms of Chaos and old Night,” and away they flew, singers, dancers, and all. The cause of this was the sudden illumination of the town with quantities of large chandeliers and bushes, the branches of which were stuck all over with great blazing torches: the effect was really beautiful, and the excessive rapture of the black multitude at the spectacle was as well worth the witnessing as the sight itself.

I never saw so many people who appeared to be so unaffectedly happy. In England, at fairs and races, half the visiters at least seem to have been only brought there for the sake of traffic, and to be too busy to be amused; but here nothing was thought of but real pleasure; and that pleasure seemed to consist in singing, dancing, and laughing, in seeing and being seen, in showing their own fine clothes, or in admiring those of others. There were no people selling or buying; no servants and landladies bustling and passing about; and at eight o’clock, as we passed through the market-place, where was the greatest illumination, and which, of course, was most thronged, I did not see a single person drunk, nor had I observed a single quarrel through the course of the day; except, indeed, when some thoughtless fellow crossed the line of the procession, and received by the way a good box of the ear from the Queen or one of her attendant Duchesses. Every body made the same remark to me; “Well, sir, what do you think Mr. Wilberforce would think of the state of the negroes, if he could see this scene?” and certainly, to judge by this one specimen, of all beings that I have yet seen, these were the happiest. As we were passing to our boat, through the market-place, suddenly we saw Miss Edwards dart out of the crowd, and seize the Captain’s arm—“Captain! Captain!” cried she, “for the love of Heaven, only look at the Red lights! Old iron hoops, nothing but old iron hoops, I declare! Well! for my part!” and then, with a contemptuous toss of her head, away frisked Miss Edwards triumphantly.

JANUARY 2.

The St. Elizabeth, which sailed from England at the same time with our vessel, was attacked by a pirate from Carthagena, near the rocks of Alcavella, who attempted three times to board her, though he was at length beaten off so that our Piccaroon preparations were by no means taken without foundation.