A Night in the Luxembourg

Remy de Gourmont

A NIGHT IN THE LUXEMBOURG

BY

REMY DE GOURMONT

WITH PREFACE

AND APPENDIX

BY ARTHUR RANSOME

JOHN W. LUCE AND COMPANY

BOSTON MCMXII

CONTENTS

TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE. By Arthur Ransome

A Night in the Luxembourg. By Remy de Gourmont

Preface

A Night in the Luxembourg

Final Note

APPENDIX: REMY de GOURMONT. By Arthur Ransome

AUTOGRAPHS—

KOPH

Reduced facsimile of the last page of M. Rose's Manuscript

TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE

A general, but necessarily inadequate, account of the personality and works of one of the finest intellects of his generation will be found in the Appendix. I am here concerned only with Une Nuit au Luxembourg, which, though it is widely read in almost every other European language, is now for the first time translated into English.

This book, at once criticism and romance, is the best introduction to M. de Gourmont's very various works. It created a "sensation" in France. I think it may do as much in England, but I am anxious lest this "sensation" should be of a kind honourable neither to us nor to the author of a remarkable book. I do not wish a delicate and subtle artist, a very noble philosopher, noble even if smiling, nobler perhaps because he smiles, to be greeted with accusations of indecency and blasphemy. But I cannot help recognising that in England, as in many other countries, these accusations are often brought against such philosophers as discuss in a manner other than traditional the subjects of God and woman. These two subjects, with many others, are here the motives of a book no less delightful than profound.

The duty of a translator is not comprised in mere fidelity. He must reproduce as nearly as he can the spirit and form of his original, and, since in a work of art spirit and form are one, his first care must be to preserve as accurately as possible the contours and the shading of his model. But he must remember (and beg his readers to remember) that the intellectual background on which the work will appear in its new language is different from that against which it was conceived. When the new background is as different from the old as English from French, he cannot but recognise that it disturbs the chiaroscuro of his work with a quite incalculable light. It gives the contours a new quality and the shadows a new texture. His own accuracy may thus give his work an atmosphere not that which its original author designed.

I have been placed in such a dilemma in translating this book. Certain phrases and descriptions were, in the French, no more than delightful sporting of the intellect with the flesh that is its master. In the English, for us, less accustomed to plain-speaking, and far less accustomed to a playful attitude towards matters of which we never speak unless with great solemnity, they became wilful parades of the indecent. It is important to remember that they were not so in the French, but were such things as might well be heard in a story told in general conversation—if the talkers were Frenchmen of genius.

There is no ugliness in the frank acceptance of the flesh, that is a motive, one among many, in this book, and perhaps more noticeable by us than the author intended. No doubt it never occurred to M. de Gourmont that he was writing for the English. We are only fortunate listeners to a monologue, and must not presume upon our position to ask him to remember we are there.

The character of that monologue is such, I think, as to justify me in tampering very little with its design. Not only is Une Nuit au Luxembourg not a book for children or young persons—if it were, the question would be altogether different—but it is not a book for fools, or even for quite ordinary people. I think that no reader who can enjoy the philosophical discussion that is its greater part will quarrel with its Epicurean interludes. He will either forgive those passages of which I am speaking as the pardonable idiosyncrasy of a great man, or recognise that they are themselves illustrations of his philosophy, essential to its exposition, and raised by that fact into an intellectual light that justifies their retention.

The prurient minds who might otherwise peer at these passages, and enjoy the caricatures that their own dark lanterns would throw on the muddy wall of their comprehension, will, I think, be repelled by the nobility of the book's philosophy. They will seek their truffles elsewhere, and find plenty.

M. de Gourmont is perhaps more likely to be attacked for blasphemy, but only by those who do not observe his piety towards the thing that he most reverences, the purity and the clarity of thought. He worships in a temple not easy to approach, a temple where the worshippers are few, and the worship difficult. It is impossible not to respect a mind that, in its consuming desire for liberty, strips away not fetters only but supports. Fetters bind at first, but later it is hard to stand without them.

His book is not a polemic against Christianity, in the same sense as Nietzsche's Anti-Christ, though it does propose an ethic and an ideal very different from those we have come to consider Christian. When he smiles at the Acts of the Apostles as at a fairy tale, he adds a sentence of incomparable praise and profound criticism: "These men touch God with their hands." It may shock some people to find that the principal speaker in the book is a god who claims to have inspired, not Christ alone, but Pythagoras, Epicurus, Lucretius, St. Paul and Spinoza with the most valuable of their doctrines. It will not, I think, shock any student of comparative religion. He will find it no more than a poet's statement of an idea that has long ceased to disturb the devout, the idea that all religions are the same, or translations of the same religion. We recognise in the sayings of Confucius some of the loveliest of the sayings of Christ, and we find them again in Mohammed. Why not admit that the same voice whispered in their ears, for this, unless we think that the Devil can give advice as good as God's, we cannot help but believe. And that other idea, that the gods die, though their lives are long, should not shock those who know of Odin, notice the lessening Christian reverence for the Jewish Jehovah, and remember the story, so often and so sweetly told, of the voices on the Grecian coast, with their cry, "Great Pan is dead! Great Pan is dead!" Turning from particular ideas to the rule of life that the book proposes, we find a crystal-line Epicureanism. Virtue is, to be happy; and sin is, where we put it. "Human wisdom is to live as if one were never to die, and to gather the present minute as if it were to be eternal." This is no doctrine that is easy to follow. The god does not offer it to the first comer, but to one who has schooled his mind to see hard things, and, having seen them, to rise above them. M. de Gourmont will tell no lies that he can avoid, especially when speaking to himself, but, if he burn himself, Phoenix-like, in the ashes of a sentimental universe, he has at least the hope of rising from the pyre with stronger wings and more triumphant flight. He will start with no more than the assumption that the universe as we know it is the product of a series of accidents. He will not persuade himself that man is the climax of a carefully planned mechanical process of evolution, nor will he hide his origin in imagery like that of Genesis, or like that which certain modern scientists are quite unable to avoid. He turns science against the scientists with the irrefutable remark that only a change in the temperature saved us from the dominion of ants. Instinct for him is arrested intellect, and he is ready to imagine man in the future doing mechanically what now he does by intention. Such ideas would crush a feeble brain or bind it with despair. They lead him to the Epicureanism that is the only philosophy that they do not overthrow. Our roses and our women make us the equals of the gods, and even envied by them.

All his criticism, not of one or two ideas alone, but of the history of philosophy, the history of woman, the history of man and the history of religion, is made with a mastery so absolute as to dare to be playful. The winter night was changed to a spring morning as the god walked in the Luxembourg, and the wintry cold of nineteenth-century science melts in the warmth of a spring-time no less magical. The book might be grim. It is clear-eyed and sparkling with dew, like a sonnet by Ronsard.

"Comme on voit sur une branche au mois de mai la rose,"

so one sees the philosophy of M. de Gourmont, not quarried stone, but a flower, so light, so delicate, as to make us forget the worlds that have been overthrown in its manufacture.

I remember near the end of The Pilgrim's Progress there is a passage of dancing. Giant Despair has been killed, and Doubting Castle demolished. The pilgrims were "very jocund and merry." "Now Christiana, if need was, could play upon the viol, and her daughter Mercy upon the lute; so, since they were so merry disposed, she played them a lesson, and Ready-to-halt would dance. So he took Despondency's daughter, Much-afraid, by the hand, and to dancing they went in the road. True, he could not dance without one crutch in his hand; but I promise you he footed it well; also the girl was to be commended, for she answered the music handsomely." Just so, in this book, on a journey no less perilous among ideas, there is an atmosphere of genial entertainment, a delight in the things of the senses illumined by a delight in the things of the mind. And in this there is no irreverence. Only those who have ceased to believe have forgotten how to dance in the presence of their God.

Perhaps the technician alone will observe the skill with which M. de Gourmont has handled the most difficult of literary forms. In translating a book one becomes fairly intimate with it, and not the least pleasure of my intimacy with Une Nuit au Luxembourg has been to notice the ease and the grace with which its author turns, always at the right moment, from ideas to images, from romance to thought. "The exercise of thought is a game," he says, "but this game must be free and harmonious." And the outward impression given by this subtly constructed book is that of an intellect playing harmoniously with itself in a state of joyful liberty. M. de Gourmont is a master of his moods, knowing how to serve them; and no less admirable than the loftiest moment of the discussion, is the Callot-like grotesque of the three goddesses, seen not as divinities but as sins, or the Virgilian breakfast under the trees.

It is possible that Une Nuit au Luxembourg may be for a few in our generation what Mademoiselle de Maupin was for a few in the generation of Swinburne, a "golden book of spirit and sense." Ideas are dangerous metal in which to mould romances, because from time to time they tarnish. Voltaire has had his moments of being dull, and Gautier's ideas do not excite us now. M. de Gourmont's may not move us to-morrow. Let us enjoy them to-day, and share the pleasure that the people of the day after to-morrow will certainly not refuse.

ARTHUR RANSOME.

A NIGHT IN THE LUXEMBOURG

BY REMY DE GOURMONT

PREFACE

There appeared in Le Temps of the 13th of February, 1906:—

"OBITUARY

"We have just learned of the sudden death of one of our confrères on the foreign press, M. James Sandy Rose, deceased yesterday, Sunday, in his rooms at 14 Rue de Médicis. Notwithstanding this English name, he was a Frenchman; born at Nantes in 1865, his true name was Louis Delacolombe. He was brought up in the United States, returned to France ten years ago, and from that time till his death was the highly valued correspondent of the Northern Atlantic Herald."

On the following day, the 14th of February, the same journal printed this note among its miscellaneous news:—

"THE MYSTERY OF THE RUE DE MEDICIS

"We announced yesterday the sudden death of M. James Sandy Rose, our confrère on the foreign press. His death seems to have taken place under suspicious circumstances. At present a woman of the Latin Quarter, Blanche B——, is strongly suspected of having been at least an accomplice to it. This woman is known for her habit of dressing in very light colours, even in mid-winter, and it was this that made the concierge notice her. She lives, moreover, behind the house of the crime—assuming that there has been a crime—in the Rue de Vaugirard. This is what is said to have happened:—

"Because M. J. S. Rose, who was of fairly regular habits, had not been seen for some days, his door was broken open, and he was discovered inanimate. He had been dead for a few hours only, a fact which does not agree with the length of time during which he had remained invisible, and still further complicates the question. It is supposed that the woman B——, after passing the night with him, put him to sleep by means of a narcotic (from which the unhappy man did not awake), or strangled him at a moment when he was defenceless; then, her theft accomplished, she would seem to have fled precipitately. An extraordinary circumstance is that in her haste she forgot her dress, and must have gone out enveloped in a big cloak. At least there is no other explanation of the presence of an elegant white robe in the rooms of M. Rose, who lived alone...."

On the next day again, there was a third echo:—

"THE MYSTERY OF THE RUE DE MEDICIS

"It appears that the young woman at first implicated in this affair has been for a fortnight at Menton with M. Pap——, a deputy from the banks of the Danube. They have both written from that place to mutual friends. The inquiry makes no progress; on the contrary..."

Other papers, that I then had the curiosity to examine, had embroidered my friend's death with still madder tales. As the police, with very good reason, made no communications to the press, the journalists pushed unreason to insanity; then, as their imaginations could go no further, they were silent.

In reality, the mixing up of Blanche B—— with the story was due solely to the chatter of a young clerk, a neighbour of M. James Sandy Rose, who had noticed a woman's dress of white material in the room. I recount, at the end of the volume, the facts which disturbed this pubescent imagination. Neither the police, who immediately lost interest in the affair, nor justice, which had never taken any, would have been able to implicate anybody in a "mystery" which, if it is really a mystery, is not one of those that police or magistrates can resolve.

For some days following, Le Temps left the Rue de Médicis alone. At the end of a fortnight, a very talkative young journalist, accompanied by an old gentleman who, like him, took notes in a pocketbook, but said nothing, came and rang at my door. He came with the intention of questioning me. I was willing enough to reply that M. James S. Rose had died of apoplexy, or, at least, suddenly; that I was his friend, and that he had made me his heir; that the rumours of crime were absurd, and the rumours of "mystery" ridiculous.

"What is there," I said, "more normal than death?"

The old gentleman acquiesced, while the young journalist murmured—

"And yet...."

"The only thing of interest," I continued, "in this banal story, sad, perhaps, for me alone, is that M. James Sandy Rose leaves an unpublished work which in his will he has charged me to bring out. I am going to do this...."

I threw a persuasive glance at the young journalist.

"It is one of the most curious books I have ever read, and, though the author was my familiar friend, it is a revelation to me...."

"Really?"

"It is indeed so. The public, without knowing what there is in the book, await it with impatience."

"Ah!"

"When you have read it, when you have merely seen it, you will agree with me."

This innocent advertisement was duly inserted in Le Temps and in Le Nouveau Courrier des Provinces, to which the old gentleman had been asked to contribute. I gained some moments of amusement, nothing more.

Here is the book, of course without commentaries. In accordance with the imperative requirements of the will, I have not corrected its style, but revised it where that was necessary, for Louis Delacolombe, educated in English, had retained some traces of his school-years in his language. I think that it was written as fast as the pen would move, and with a feverish hand, in the space of a few days.

I have summarised in a final note the results of my personal inquiry. There is no need to read it, but I think, however, that it will interest those whose curiosity is aroused by my friend's enigmatical narrative.

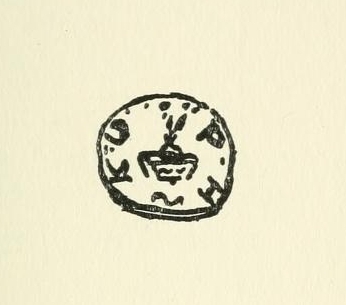

P. S.—The drawing below, which is from the hand of M. Sandy Rose, and which I have inserted at the place that he had indicated, may have a meaning, but, if so, I have been unable to penetrate it. It seems to represent a Greek medal dedicated to the goddess Core. But KOPH means also young girl, and even doll. Besides, are such medals known?

A NIGHT IN THE LUXEMBOURG...

I am certainly drunk, yet my lucidity is very great. Drunk with love, drunk with pride, drunk with divinity, I see clearly things that I do not very well understand, and these things I am about to narrate. My adventure unrolls before my eyes with perfect sharpness of outline; it is a piece of faery in which I am still taking part; I am still in the midst of lights, of gestures, of voices.... She is there. I have only to turn my head to observe her; I have only to rise to go and touch her body with my hands, and with my lips.... She is there. A privileged spectator, I have carried away with me the queen of the spectacle, a proof that the spectacle was one of the days of my actual life. That day was a night, but a night lit by a Spring sun, and, behold, it continues, night or day, I do not know.... The queen is there. But I must write.

The abridged story of my adventure will appear to-morrow morning in the Northern Atlantic Herald, and will soon make the circuit of the American press, to return to us through the English agencies: but that does not satisfy me. I telegraphed, because it was my duty; I write, because it is my pleasure. Besides, experience has taught me that news gains rather in precision than in exactitude in its journeys from cable to cable, and I am anxious for exactitude.

With what happiness I am going to write! I feel in my head, in my fingers, an unheard-of facility....

On the first intelligence of the pious riots that transformed into fortresses our peaceful churches, peaceful after the manner of old haunted castles, the newspaper that I have represented for ten years asked me, with a certain impatience, for details. As I live in the Rue de Médicis, having a long-standing passion for the Luxembourg, its trees, its women, its birds, I went down towards the Place Saint-Sulpice. The square was occupied by children, playing as they returned from school; round it rolled great empty omnibuses; now and again a tramcar widowed of a horse left with difficulty, while another struggled up and turned round without grace. My prolonged stay in Paris has made me an idler like every one else. Nothing astonishes me, and everything amuses me. Besides, I am by nature at once sceptical and inquisitive. That is why, when I lifted my eyes towards the church, my attention was vividly excited by the fact that the windows on the side towards the Rue Palatine seemed lit by the rays of a brilliant sunset. But the sun had not shone that day, and, even if the sky had been clear, no reflection could, at that late hour, light the south side of the church of Saint-Sulpice. I thought of a fire, but no trace of one was to be seen in the sky. Something unusual was certainly going on inside. I hurried towards the door in the Rue Palatine. As I advanced, without losing sight of the windows, I perceived that the light seemed to be coming down the length of the church, as if blazing torches were being carried about in this transept of the nave. At the moment when I went in, the windows by the choir began to shine, while those nearer the front of the church were now obscure.

Pushing open the door, I went towards the chapel of the Virgin, behind the high altar. It seemed lit up as if for a feast-day, and yet I heard no chanting, no music, I perceived no noise. I advanced with steps that I thought precipitate, but which were, on the contrary, very slow, for, to my great shame, I felt myself trembling; in the deep silence of this mournful basilica my heart, it seemed to me, beat like a bell. At one moment the lights of the chapel shone with such brilliance that I had to shut my eyes. When I reopened them, it was dark, and some lamps alone shed their vague, accustomed lights in the now complete obscurity.

A man stood upright, his hand resting on the closed railings of the chapel. He seemed in every way ordinary. Nothing was remarkable but the profound attention with which he was observing the statue of the Virgin. I wished to keep on my way, anxious to question some priest or sacristan, first on the luminous phenomenon, which puzzled me very much, and then, as was my duty, on the events which were doubtless preparing for the next day; I wished to keep on my way, I was in a hurry to finish my business, for I do not find churches, especially at evening, agreeable resting-places; I wished to go away, I wished to speak, but I felt that I was fastened to the flag-stones, I trembled more and more, and, finally, I could not prevent myself from observing the unknown man. I saw him in profile. His hair, worn short, slightly curled, seemed to me to be chestnut, like his beard, which was full, not very thick on the cheeks, and of moderate length. His clothes were much like my own; they were those of a gentleman, correct but unpretentious. I felt I was going mad, in my inability to explain the interest that stopped me before so common a sight. I understood no better the attention with which the unknown stared at the Virgin.

A connoisseur of art would have quickly passed on; a devotee would have knelt. I was beginning to lose my head, to think that I was ill, when the man, so ordinary and yet so singular, turned his eyes towards me. These eyes, extremely brilliant, completed my discomfiture. I lowered my own, not before I had observed that the very pale face was one of the gentlest and most understanding I had ever seen. I even thought that I discerned on those delicate features a smile of infinitely benevolent irony, like those I have seen in certain portraits of beautiful Lombard women. This smile enchanted and intimidated me at the same time. "It would be a great happiness," I said to myself, my eyes still lowered, "if I could once again enjoy that smile," but I dared not look at the unknown, who, I divined, was still observing me. I no longer trembled, but felt myself in that state of happy confusion which one experiences in the presence of a woman whom one loves and fears. I expected nothing, and yet it seemed to me that something was going to happen.

We were about three paces from each other. By stretching our arms we should have been able to touch each other's hands.

"Come," said he.

This single word sufficed to put an end to all my disquietude. The voice was very agreeable. It filled me with a gentle emotion. At the same time I became as free and as content as in the presence of a very old and dearly loved friend. It seemed to me that I had known from all time this unknown of a moment before. I found that I was familiar with his face, his manner, his look, his voice, his mind, his very clothes. An irresistible force moved me to answer him, and to answer him in these words:—

"I follow you, my friend."

All my surprise had disappeared, and, although I was perfectly conscious that the adventure was singular, I was in such a state of mind that I did not feel its singularity.

I went up to him. He took my arm, and the action seemed quite natural. Were we not old friends? Had I not known him since I was three or four years old? Yes, and although he was certainly much older than I, he had played with me in my cot. All this settled itself clearly in my head. I repeat, from that moment until sunrise the next morning, that is to say, all the time I spent with him, I had not one moment of astonishment. What happened, what I heard, what I said, the unusual phenomena, everything seemed to me to be perfectly in place.

So I went up to him, and, when his arm was passed under mine, which I folded very respectfully and with a lover's joy, a long and precious conversation began between us.

HE

It is this that they call my mother! They are full of such good intentions. Admit, my friend, that they are good people.

I

Very good people. You do not think your mother well portrayed?

HE

I have had so many mothers that this image doubtless resembles one of the women who have believed that they gave birth to me; it is their innocence that makes me smile, their virginal conception of maternity, the white robe, the blue scarf. And yet, this church, one of the ugliest in the whole world, is one of the least puerile. The priests who serve it have preserved some intellectual illusion. They have a scrupulous and argumentative piety. The miracles anciently described seem to them proved by their very antiquity. They know that I walked on the waters, one tempestuous evening, but, if they had seen the windows of their church on fire with lights, would they have believed their eyes? You saw, you believed, and you came, my friend. That light shone for you alone.

I

Oh, my friend!

HE

To speak to mankind I need a man as intermediary, and I chose you, I gave you a sign. You were not obliged to respond. My power is not such as to compel men's wills. I can seduce; but I cannot command.

I

I was greatly surprised, I was frightened, but I walked as if to happiness, as if towards a moment of love. But why did the light go out, at the moment when I came near you?

HE

Because your curiosity had become desire. No longer could anything stop you. The iron was on its way towards the magnet. Are you happy?

I

It seems to me that my life is being fulfilled; it seems to me that my past days were only a preparation for the present hour.

HE

Then you are happy? You are going to be much more so. There are things of which mankind have always appeared to be ignorant. When you have heard them from my lips you will, in that moment, have received the courage to repeat them, and that will win you an eternal glory, a glory that will last as long as the earth itself, perhaps as long as the civilisation of which you are a part.

I

Is there not another eternity, a true eternity?

My master—for I now felt that this old friend was my master still more than my friend—my master was kind enough to smile, looking at me with tender irony, but he did not answer my question.

"Let us go," he said, after a moment's silence, "and walk in the Luxembourg."

I

Not really?

This time, he laughed indeed. He laughed softly.

We walked all round the sombre church, and left it by the Rue Palatine. I noticed that he took no holy water, and, even, as I stretched out my hand towards the stone shell, he murmured:

"Useless."

It was now night. We reached the Rue Servandoni in silence. The rare passengers met or passed us without emotion, without curiosity. A young woman, however, who was coming slowly down the street, observed my companion with eyes that seemed on fire. Perhaps, if he had been alone, she would have been still bolder. An idea, madder than the young woman's glance, crossed my mind.

"She looked at you," I said, "as if she knew you."

HE

Everybody recognises me, when I wish it. That young woman does not know who I am. She thinks me a man like other men, and yet, if I had been alone, her glance would have been much more lively, for she desires soft words, she desires kisses. But what would be her destiny, if I yielded to her mute sympathy! The women whom I love lose all reasonable notions of life, and I have no sooner touched their hands, caressed their hair, than all their flesh weeps with pleasure. If I insist, they melt like figs in my sunlight. Sweet flavour and cruel! If I withdraw myself from them they die of grief, and if I stay with them they die of love.

I

The mystics have said something of that.

HE

Something of it they have shown, but wrapped in the withered herbs of their piety.

I

Saint Teresa ...

HE

She believed that I loved her with passion. That fatuity made me leave her. Hers was the solidest woman's heart I have ever met, and with it what facility in self-deceit. She really thought she died in my arms: I was far away. However, in that supreme moment, I consoled her with a thought, for she had earned it by her constancy. What she wrote herself is not without interest for mankind, but the priests, who set themselves to excite her genius, inspired her with many follies, such as her vision of hell. I shall not tell you, my friend, who are the women I have most loved. Scarcely one of them has left a name among you. A woman who is loved and loves does not pass her time, like the illustrious Teresa, in describing the stations of love. She lives and she dies, and that is all.

While I was considering these words, which a little troubled my understanding, we had arrived before the railing of the garden. There I stopped, observing the sombre drawing of the great naked trees. Heavy black clouds were passing in the sky, that was very feebly lit by an invisible crescent of moon.

"How gloomy," I said, "is this park on a winter evening, and gloomier still through these bars."

But the gate opened a little way, and we went in. I had seen so many strange things, heard so many strange words, felt so many strange emotions, that this new miracle gave me but a mediocre surprise. We were in the garden.

"Let us go," he said, "towards the roses."

I

Towards the rose-trees.

HE

Towards the roses.

A soft and clear daylight was born as we advanced. The trees, suddenly in leaf, the chestnuts blossoming in shafts of white and red, were filled with the songs of birds. Blackbirds, on the topmost branches, launched their shrill calls. Bees were already murmuring by; a fly settled on my hand.

The great flower-bed was in full bloom. A perfume enveloped me with a precious sweetness. We disturbed a cat that was stalking two cooing pigeons. My friend plucked a red rose, then a white, then a yellow. At this moment it seemed to be five o'clock in the morning of a beautiful summer day.

I

I am happy. I am happy.

HE

Roses, these roses, are enough to make me jealous of men. The rose of your gardens, the woman of your civilisation, these are two creations that make you the equals of the gods. And to think that you still regret the earthly paradise! Eve! Eve, my friend, was a milkmaid, the pleasure of a bird-catcher or an early-rising oxherd. Eve, when you have all these real young women to enchant your eyes and make desperate your dreams!

I

She was, however, a divine work. Your father ...

But I said no more, trembling with happiness. Three young women were coming towards us. They were dressed in white. Delicate garlands of flowers adorned their corn-coloured hair. They walked slowly, holding each other's hands; their smiles made a light within the light. At the sight of the new roses, they all cried out together like children, and stayed, stretching their arms towards the rose-trees, timorous and troubled by desire.

I watched, a prisoner of the spell, but my friend, with the ease of a king, made a few steps towards them, and offered them the roses he had plucked. They took them, blushing, and slipped them into their girdles. She who was the tallest, who had the most beautiful hair, and the most beautiful eyes, thanked him with a smile and a few words, and then added:—

"We were looking for you."

HE

They say that when one looks for me, he always finds me.

Then there was charming laughter, laughter that made my heart laugh.

SHE

How beautiful are the roses on this earth!