Corea: The Hermit Nation

William Elliot Griffis

Works by Wm. Elliot Griffis

- THE MIKADO’S EMPIRE

- JAPANESE FAIRY WORLD

- COREA, THE HERMIT NATION

- MATTHEW CALBRAITH PERRY

- THE LILY AMONG THORNS

- HONDA, THE SAMURAI

- SIR WILLIAM JOHNSON

- JAPAN: IN HISTORY, FOLK-LORE, AND ART

- BRAVE LITTLE HOLLAND

- THE RELIGIONS OF JAPAN

- TOWNSEND HARRIS

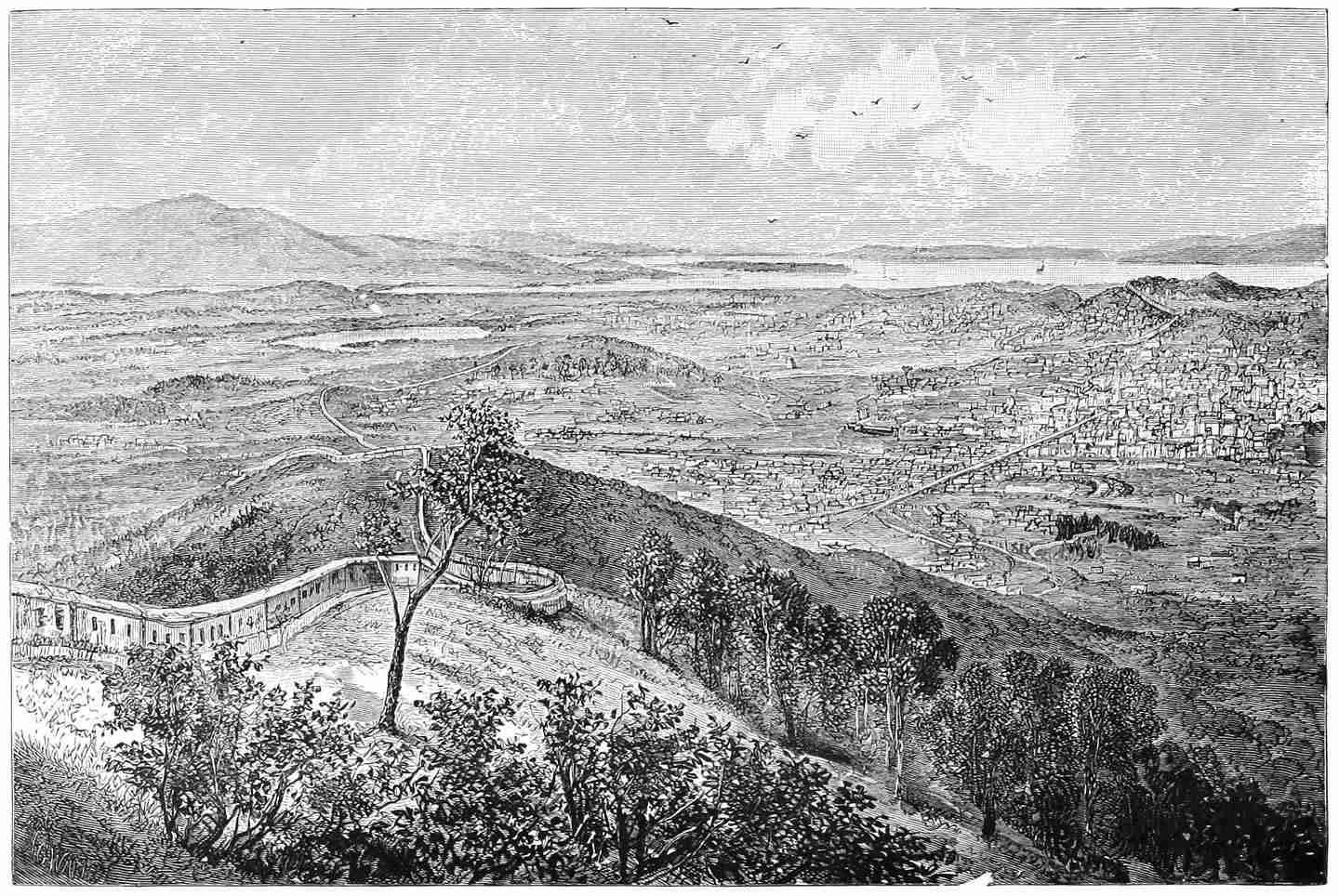

A CITY IN COREA.

II.—POLITICAL AND SOCIAL COREA

III.—MODERN AND RECENT HISTORY

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1911

Copyright, 1882, 1888, 1897, 1904, 1907, 1911

By CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

TO

ALL COREAN PATRIOTS:

WHO SEEK

BY THE AID OF SCIENCE, TRUTH, AND PURE RELIGION,

TO ENLIGHTEN

THEMSELVES AND THEIR FELLOW-COUNTRYMEN,

TO RID

THEIR LAND OF SUPERSTITION, BIGOTRY, DESPOTISM, AND

PRIESTCRAFT—BOTH NATIVE AND FOREIGN—

AND TO PRESERVE

THE INTEGRITY, INDEPENDENCE, AND HONOR, OF THEIR COUNTRY;

THIS UNWORTHY SKETCH

OF

THEIR PAST HISTORY AND PRESENT CONDITION

IS DEDICATED. [v]

PREFACE TO THE NINTH EDITION.

The year 1910 saw the Land of the Plum Blossom and the Islands of the Cherry Blooms united. In this ninth edition of a work which for nearly thirty years has been a useful hand-book of information—having, by their own unsought confession, inspired not a few men and women to become devoted friends and teachers of the Corean people—I have made some corrections and added a final chapter, “Chō-sen: A Province of Japan.” Besides outlining in brief the striking events from 1907 to 1911, I have analyzed the causes of the extinction of Corean sovereignty, aiming in this to be a disinterested interpreter rather than a mere annalist.

Although the sovereignty of Corea, first recognized and made known to the world by the Japanese in their treaty of 1876, has been, through the logic of events, destroyed, I doubt not that the hopes of twelve millions of people will be increasingly fulfilled under the new arrangement. Not in haste, but only after long compulsion, did the statesmen of Japan assume a responsibility that may test to the full their abilities and those of their successors. The severe criticisms, in Japan itself, of the policy of the Tokio government bear witness to the sensitiveness of the national conscience in regard to the treatment of their colonies. In this respect, as in so many other points of public ethics, the Japanese are ranging themselves abreast with the leading nations that are making a world-conscience.

In sending forth what may be the final edition of a work, with the title of which time has had its revenges, while the contents are still of worth, the author thanks heartily all who, from 1876, when the work was planned, until the present time, have assisted in making this book valuable to humanity.

W. E. G.

Ithaca, N. Y., June 27, 1911. [vii]

PREFACE TO THE EIGHTH EDITION.

When in October, 1882, the publishers of “Corea the Hermit Nation” presented this work to the public of English-speaking nations, they wrote:

“Corea stands in much the same relation to the traveller that the region of the pole does to the explorer, and menaces with the same penalty the too inquisitive tourist who ventures to penetrate its inhospitable borders.”

For twenty-four years, this book, besides enjoying popular favor, has been made good use of by writers and students, in Europe and America, and has served even in Corea itself as the first book of general information to be read by missionaries and other new comers. In this eighth edition, I have added to the original text, ending with Chapter XLVIII (September, 1882), five fresh chapters: on The Economic Condition of Corea; International Politics: Chinese and Japanese; The War of 1894: Corea an Empire; Japan and Russia in Conflict; and Corea a Japanese Protectorate, bringing the history down to the late autumn of 1906.

Within the brief period of time treated in these new chapters, the centre of the world’s politics has shifted from the Atlantic and the Mediterranean to the waters surrounding Corea, the strange anomaly of dual sovereignty over the peninsular state has been eliminated, and the military reputation of China ruined, and that of Russia compromised. The rise of Japan, within half a century of immediate contact with the West, to the position of a modern state, able first to humiliate China and then to grapple successfully with Russia, has vitally affected Corea, on behalf of whose independence Japan a second time went to war with a Power vastly greater in natural resources than herself. In this period [viii]also, the United States of America has become one of the great Powers interested in the politics of Asia, and with which the would-be conquerors of Asiatic peoples must reckon.

The present or eighth edition shows in both text and map, not only the swift, logical results both of Japan’s military and naval successes in Manchuria and on the sea of Japan and of her signal diplomatic victory at Portsmouth, but more. It makes clear the reasons why Corea, as to her foreign relations, has lost her sovereignty.

The penalty laid upon the leaders of the peninsular kingdom for making intrigue instead of education their work, and class interests instead of national welfare their aim, is also shown to be pronounced—less by the writer than by the events themselves—in the final failure of intriguing Yang-banism, in May, 1906. The Japanese, in the administration of Corea, are like the other protecting nations, British, American, French, German, now on a moral trial before the world.

In again sending forth a work that has been so heartily welcomed, I reiterate gladly my great obligations to the scholars, native and foreign, who have so generously aided me by their conversation, correspondence, criticism, and publications, and the members of the Korean Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, who have honored me with membership in their honorable body. My special obligations are due to our late American Minister, H. N. Allen, for printed documents and illustrative matter; to Professor Homer B. Hulbert, Editor of The Korea Review, from the pages of which I have drawn liberally, and to the Editor of The Japan Mail, the columns of which are rich in correspondence from Corea. I would call attention also to the additions made upon the map at the end of the volume.

I beg again the indulgence of my readers, especially of those who by long residence upon the soil, while so thoroughly able to criticize, have been so profuse in their expression of appreciation. From both sides of the Atlantic and Pacific have come these gratifying tokens, and to them as well as to my publishers, I make glad acknowledgments in sending forth this eighth edition.

W. E. G.

Ithaca, N. Y., December 12, 1906. [ix]

PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION.

In the year 1871, while living at Fukui, in the province of Echizen, Japan, I spent a few days at Tsuruga and Mikuni, by the sea which separates Japan and Corea. Like “the Saxon shore” of early Britain, the coast of Echizen had been in primeval times the landing-place of rovers, immigrants, and adventurers from the continental shore opposite. Here, at Tsuruga, Corean envoys had landed on their way to the mikado’s court. In the temple near by were shrines dedicated to the Corean Prince of Mimana, and to Jingu Kōgō, Ojin, and Takénouchi, whose names in Japanese traditions are associated with “The Treasure-land of the West.” Across the bay hung a sweet-toned bell, said to have been cast in Corea in A.D. 647; in which tradition—untested by chemistry—declared there was much gold. Among the hills not far away, nestled the little village of Awotabi (Green Nook), settled centuries ago by paper-makers, and visited a millenium ago by tribute-bearers, from the neighboring peninsula; and famous for producing the crinkled paper on which the diplomatic correspondence between the two nations was written. Some of the first families in Echizen were proud of their descent from Chō-sen, while in the villages, where dwelt the Eta, or social outcasts, I beheld the descendants of Corean prisoners of war. Everywhere the finger of tradition pointed westward across the waters to the Asian mainland, and the whole region was eloquent of “kin beyond sea.” Birds and animals, fruits and falcons, vegetables and trees, farmers’ implements and the potter’s wheel, names in geography and things [x]in the arts, and doctrines and systems in religion were in some way connected with Corea.

The thought often came to me as I walked within the moss-grown feudal castle walls—old in story, but then newly given up to schools of Western science and languages—why should Corea be sealed and mysterious, when Japan, once a hermit, had opened her doors and come out into the world’s market-place? When would Corea’s awakening come? As one diamond cuts another, why should not Chō-ka (Japan) open Chō-sen (Corea)?

Turning with delight and fascination to the study of Japanese history and antiquities, I found much that reflected light upon the neighbor country. On my return home, I continued to search for materials for the story of the last of the hermit nations. No master of research in China or Japan having attempted the task, from what Locke calls “the roundabout view,” I have essayed it, with no claim to originality or profound research, for the benefit of the general reader, to whom Corea “suggests,” as an American lady said, “no more than a sea-shell.” Many ask “What’s in Corea?” and “Is Corea of any importance in the history of the world?”

My purpose in this work is to give an outline of the history of the Land of Morning Calm—as the natives call their country—from before the Christian era to the present year. As “an honest tale speeds best, being plainly told,” I have made no attempt to embellish the narrative, though I have sought information from sources from within and without Corea, in maps and charts, coins and pottery, the language and art, notes and narratives of eye-witnesses, pencil-sketches, paintings and photographs, the standard histories of Japan and China, the testimony of sailor and diplomatist, missionary and castaway, and the digested knowledge of critical scholars. I have attempted nothing more than a historical outline of the nation and a glimpse at the political and social life of the people. For lack of space, the original manuscript of “Recent and Modern History,” part III., has been greatly abridged, and many topics of interest have been left untouched.

The bulk of the text was written between the years 1877 and [xi]1880; since which time the literature of the subject has been enriched by Ross’s “Corea” and “Corean Primer,” besides the Grammar and Dictionary of the Corean language made by the French missionaries. With these linguistic helps I have been able to get access to the language, and thus clear up doubtful points and obtain much needed data. I have borrowed largely from Dallet’s “Histoire d’Eglise de Corée,” especially in the chapters devoted to Folk-lore, Social Life, and Christianity. In the Bibliography following the Preface is a list of works to which I have been more or less indebted.

Many friends have assisted me with correspondence, advice, or help in translation, among whom I must first thank my former students, Haségawa, Hiraii, Haraguchi, Matsui, and Imadatté, and my newer Japanese friends, Ohgimi and Kimura, while others, alas! will never in this world see my record of acknowledgment—K. Yaye′ and Egi Takato—whose interest was manifested not only in discussion of mooted points, but by search among the book-shops in Kiōto and Tōkiō, which put much valuable standard matter in my hands. I also thank Mr. Charles Lanman, Secretary of the Legation of Japan in Washington, for four ferrotypes taken in Seoul in 1878 by members of the Japanese embassy; Mr. D. R. Clark, of the United States Transit of Venus Survey, for four photographs of the Corean villages in Russian Manchuria; Mr. R. Idéura, of Tōkiō, for a set of photographs of Kang-wa and vicinity, taken in 1876, and Mr. Ozawa Nankoku, for sketches of Corean articles in Japanese museums. To Lieutenant Wadhams, of the United States Navy, for the use of charts and maps made by himself while in Corea in 1871, and for photographs of flags and other trophies, now at Annapolis, captured in the Han forts; to Fleet-Surgeon H. O. Mayo, and other officers of the United States Navy, for valuable information, I hereby express my grateful appreciation of kindness shown. I would that Admiral John Rodgers, Commodore H. C. Blake, and Minister F. F. Low were living to receive my thanks for their courtesies personally shown me, even though, in attempting to write history, I have made criticisms also. To Lieutenant N. Y. Yanagi, of the Hyrographic Bureau, of the Japanese Navy, for a [xii]set of charts of the coast of Corea; to Mr. Metcalfe, of Milwaukee, for photographs of Coreans; to Miss Marshall, of New York, for making colored copies of the battle-flags captured by our naval battalion in 1871, and for the many favors of correspondents—in St. Petersburg, Mr. Hoffman Atkinson; in Peking, Jugoi Arinori Mori; in Tōkiō, Dr. D. B. McCartee, Hon. David Murray, Rev. J. L. Amerman, and others whose names I need not mention. To Gen. George W. McCullum, Vice-President, and to Mr. Leopold Lindau, Librarian, of the American Geographical Society, I return my warmest thanks; as well as to my dear wife and helpmeet, for her aid in copying, proof-reading, suggestions, and criticism during the progress of the work.

In one respect, the presentation of such a subject by a compiler, while shorn of the fascinating element of personal experience, has an advantage even over the narrator who describes a country through which he has travelled. With the various reports of many witnesses, in many times and places, before him, he views the whole subject and reduces the many impressions of detail to unity, correcting one by the other. Travellers usually see but a portion of the country at one time. The compiler, if able even in part to control his authorities, and if anything more than a tyro in the art of literary appraisement, may be able to furnish a hand-book of information more valuable to the general reader.

In the use of my authorities I have given heed to Bacon’s advice—tasting some, chewing others, and swallowing few. In ancient history, original authorities have been sought, and for the story of modern life, only the reports of careful eye-witnesses have been set down as facts; while opinions and judgments of alien occidentals concerning Corean social life are rarely borrowed without due flavoring of critical salt.

Corean and Japanese life, customs, beliefs, and history are often reflections one of the other. Much of what is reported from Corea, which the eye-witnesses themselves do not appear to understand, is perfectly clear to one familiar with Japanese life and history. China, Corea, and Japan are as links in the same chain of civilization. Corea, like Cyprus between Egypt and Greece, will yet [xiii]supply many missing details to the comparative student of language, art, science, the development of civilization, and the distribution of life on the globe.

Some future writer, with more ability and space at command than the undersigned, may discuss the question as to how far the opening of Corea to the commerce of the world has been the result of internal forces; the scholar, by his original research, may prepare the materials for a worthy history of Corea during the two or three thousand years of her history; the geologist or miner may determine the question as to how far the metallic wealth of Corea will affect the monetary equilibrium of the world. The missionary has yet to prove the full power of Christianity upon the people—and before Corean paganism, any form of the religion of Jesus, Roman, Greek or Reformed, should be welcomed; while to the linguist, the man of science, and the political economist, the new country opened by American diplomacy presents problems of profound interest.

W. E. G.

Schenectady, N. Y., October 2, 1882. [xv]

BIBLIOGRAPHY.

The following is a list of books and papers containing information about Corea. Those of primary value to which the compiler of this work is specially indebted are marked with an asterisk (*); those to which slight obligation, if any, is acknowledged with a double asterisk; and those which he has not consulted, with a dagger (†). See also under The Corean Language and Cartography, in the Appendix.

* History of the Eastern Barbarians. “Book cxv. contains a sketch of the tribes and nations occupying the northeastern seaboard of China, with the territory now known as Manchuria and Corea.” This extract from a History of the Later Han Dynasty (25–220 A.D.), by a Chinese scholar of the fifth century, has been translated into English by Mr. Alexander Wylie, and printed in the Revue de l’Extrême Orient, No. 1, 1882. Du Halde and De Mailla, in French, and Ross, in English, have also given the substance of the Chinese writer’s work, which also furnishes the basis of Japanese accounts of Corean history previous to the fourth century.

† The Subjugation of Chaou-seen, by A. Wylie. (Atti del IV. Cong. int. degli Orient, ii., pp. 309–315, 1881.) This fragment is a translation of the 95th book of the History of the Former Han Dynasty of China.

* Empire de la Chine et la Tartarie Chinoise, par P. du Halde.

* The Kōjiki and Nihongi, written in Japan during the eighth century, throws much light on the early history of Corea.

* Wakan-San-sai Dzuyé. Article on Chō-sen in this great Japanese Encyclopædia.

† Tong-Kuk Tong-Kan (General View of the Eastern Kingdom), a native Corean history written in Chinese.

* Zenrin Koku Hoki (Precious Jewels from a Neighboring Country), by Shiuho. Japan, 1586.

* Corea, its History, Manners, and Customs, by John Ross. 1 vol., pp. 404. Illustrations and maps. Paisley, 1880.

* The Chinese Reader’s Manual, by W. Fred. Mayers. 1 vol., pp. 440. Shanghae, 1874. An invaluable epitome of Chinese history, biography, chronology, bibliography, and whatever is of interest to the student of Chinese literature.

* Kō-chō Rekidai Enkaku Zukai. Historical Periods and Changes of the Japanese Empire, with maps and notes, by Otsuki Tōyō. [xvi]

** San Koku Tsu-ran To-setsu. Mirror of the Three [Tributary] Kingdoms, Chō-sen, Riu kiu, and Yezo, by Rin Shihei, 1785. This work, with its maps, was translated into French by J. Klaproth, and published in Paris, 1832. 1 vol. 8vo, pp. 288, of which pp. 158 relate to Chō-sen. Digested also in Siebold’s Archiv.

** Archiv zur Beschreibung von Japan, by Franz von Siebold. This colossal work contains much matter in text and illustrations relating to Corea, and the digest of several Japanese books, in the part entitled Nachrichten über Korai, Japan’s Bezüge mit der Koraischen Halbinsel und mit Schina.

** Corea und dessen Einfluss auf die Bevölkerung Japans. Zeit. für Ethnologie, Zitzungbericht VIII. p. 78, 1876. P. Kempermann.

** O Dai Ichi Ran. This work, containing the annals of the emperors of Japan, is a bird’s-eye view of the principal events in Japanese history, written in the style of an almanac, which Titsingh copied down from translations made by Japanese who spoke Dutch. Klaproth revised and corrected Titsingh’s work, and published his own version in 1834. Paris and London, 8vo, pp. 460. This work contains many references to Corea and the relations of the two countries, transcribed from the older history.

** Tableaux Historiques de l’Asie, depuis la monarchie de Cyrus jusque nos jours, accompagnes de recherches historiques et ethnographiques, etc. Par J. Klaproth, Paris, 1826. Avec un atlas in folio. This manual of the political geography of Asia is very useful, but not too accurate.

† A Heap of Jewels in a Sea of Learning (Gei Kai Shu Jin; Jap. pron.). A chapter from this Chinese book treats of Corea.

† Chō-sen Hitsu Go-shin. A collection of conversations with the pen, with a Corean who could not speak Japanese. By Ishikawa Rokuroku Sanjin, Yedo.

* The Classical Poetry of the Japanese. By Basil Hall Chamberlain. London, 1880.

** An Outline History of Japanese Education, New York, 1876. This monograph, prepared for the Centennial Exposition at Philadelphia, reviews the educational influences of Corea upon Japan. The information given is, with other data, from Klaproth, utilized in Pickering’s Chronological History of Plants, by Charles Pickering, M.D., Boston, 1879.

* Japanese Chronological Tables. By William Bramsen, Tōkiō, 1880. An invaluable essay on Japanese chronology, which was, like the Corean, based on the Chinese system. We have used this work of the lamented scholar (who died a few months after it was published) in rendering dates expressed in terms of the Chinese into those of the Gregorian or modern system.

** History of the Mongols. 3 vols. pp. 1827. London, 1876. By Henry Howorth. This portly work is full of the fruits of research concerning the people led by Genghis Khan. It contains excellent maps of Asia, and of Mongolia, and Manchuria, illustrating the Mongol conquests.

† Chō-sen Ki-che. (Memorandum upon Corean Affairs.) The Chinese ambassador sent by the Ming emperor in 1450, gives in this little work an account of his journey, which throws light upon the political and geographical situation of Chō-sen and China at that time. Quoted by M. Scherzer, but not translated. [xvii]

* Nihon Guaishi. Military History of Japan, by Rai Sanyo. This is the Japanese standard history. It was published in 1827 in twenty-two volumes. It covers the period from the Taira and Minamoto families to that of the Tokugawa in the seventeenth century. The first part of this work was translated into English by Mr. Ernest Satow, and published in The Japan Mail at Yokohama, 1872–74. In the latter portion the invasion of Chō-sen, 1592–97, is outlined.

* Chō-sen Seito Shimatsŭki. A work in five volumes, giving an account of the embassies, treaties, documents relating to the invasion of 1592–97, with an outline of the war, geographical notes, with nine maps by Yamazaki Masanagi and Miura Katsuyoshi.

* Illustrated History of the Invasion of Chō-sen. Written by Tsuruminé Hikoichiro. Illustrations by Hashimoto Giokuron. 20 vols. Yedo, 1853. This popular work, besides an outline of Corean history from the beginning, condensed from local legends and Chinese writers, details the operations of war and diplomacy relating to Hidéyoshi’s invasion. It is copiously illustrated with first-class wood engravings. It has not been translated.

* Chō-sen Monogatari. A Diary and Narrative of the Japanese Military Operations in Chō-sen during the Campaign of 1594–97, by Okoji Hidémoto. Copied out and published in 1672, and again in 1849. This narrative of an eye-witness was written by the author at the time of the events described, and afterward copied by his own son and deposited in the temple at which his ancestors worshipped. This vivid and spirited story of the second invasion of Chō-sen by Hidéyoshi has been translated into German by Dr. A. Pfizmaier, under the title Der Feldzug der Japaner gegen Corea, im Jahre, 1597. 2 vols. Vienna, 1875: 4to, pp. 98; 1876: 4to, pp. 58.

** Chohitsuroku. History of the Embassies, Treaties, and War Operations during the Japanese Invasion. This work is by a Corean author, who was one of the ministers of the king throughout the war. It is written in Chinese, has a map, and gives the Corean side of the history of affairs from about 1585 to 1598. 3 vols.

* Three Severall Testimonies Concerning the mighty Kingdom of Coray, tributary to the Kingdom of China, and bordering upon her Northeastern Frontiers, and called by the Portugales, Coria, etc., etc., collected out of Portugale yeerely Japonian Epistles, dated 1590, 1592, 1594. In Hakluyt, London, 1600.

* Hidéyoshi’s Invasion of Korea. Trans. Asiatic Society of Japan. By W. G. Aston. In these papers Mr. Aston gives the results of a study of the campaign of 1592–97, as found in Japanese and Corean authors.

** Lettre Annuelle de Mars 1593, ecrite par le P. Pierre Gomez au P. Claude Acquavira, general de la Compagnie de Jesus. Milan, 1597, p. 112 et suiv. In Hakluyt.

* Histoire de la Religion Chrétienne au Japon. Par Leon Pages. 2 vols., text and documents. Paris, 1869.

** Histoire des deux Conquerans Tartares, qui ont subjugé la Chine, par le R. P. Pierre Joseph D’Orliens.

* Chō-sen Monogatari (Romantic Narrative of Travels in Corea), by two Men from Mikuni, in Echizen, cast ashore in Tartary in 1645. This work is digested in Siebold’s Archiv. [xviii]

* Narrative of an Unlucky Voyage and Imprisonment in Corea, 1653–1667 In Astley’s and Pinkerton’s Voyages. By Hendrik Hamel.

* Imperial Chinese Atlas, containing maps of China and each of the Provinces, including Shing-king and the neutral strip.

* Histoire de l’Eglise de Corée, par Ch. Dallet. 2 vols. 8vo, pp. 982. Paris, 1874. This excellent work contains 192 pages of introduction, full of accurate information concerning the political social life, geography, and language of Corea, and a history of the introduction and progress of Roman Christianity, and the labors of the French missionaries, from 1784–1866. It contains also a map and four charts of Corean writing.

* Une Expedition en Corée. In la Tour du Monde for 1873 there is an article of 16 pp. (401–417) with illustrations, by M. H. Zuber, a French naval officer, who was in Corea in 1866 under Admiral Roze. An excellent descriptive paper by an eye-witness.

* Diary of a Chinese Envoy to Corea (Journal d’une Mission en Corée), by Koei Ling, Ambassador of his Majesty the Emperor of China, to the court of Chō-sen in 1866. Translated from the Chinese into French by F. Scherzer, Interpreter to the French Legation at Peking. 8vo, pp. 77. Paris, 1882. This journal of the last Chinese ambassador to Seoul is well rendered, and is copiously supplied with explanatory notes, and a colored map of the author’s route from Peking through Chili, Shing-king, via Mukden, and through three provinces of Corea to Seoul.

† Many memoirs and special papers prepared by French officers in the expedition to Corea in 1866 were prepared and read before local societies at Cherbourg, Lyons, etc.

† Expedition de Corée. Revue maritime et coloniale, February, 1867, pp. 474–481.

† Paris Moniteur, 1866–67.

** Lettre sur la Corée et son Eglise Chrétienne. Bulletin de la Société Geographique de Lyon, 1876, pp. 278–282, and June, 1870, pp. 417–422, and map.

** The Corean Martyrs. By Canon Shortland. 1 vol., pp. 115. London. Compiled from the letters of the French missionaries.

** Nouvelle Geographie Universelle. This superb treasury of geographical science, still unfinished, contains a full summary of our knowledge of Corea, especially showing the prominent part which French navigators, scholars, and missionaries have taken in its exploration. Paris.

** Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean and Round the World. By William R. Broughton. 2 vols. 4to, with atlas. London, 1804.

** Voyage Round the World. By Jean François de Gallou de La Perouse. London, 1799.

** Voyages to the Eastern Seas in the year 1818. By Basil Hall. New York, London, and revised by Captain Hall in 1827. Jamaica, N. Y.

* Narrative of a Voyage in His Majesty’s late Ship Alceste, to the Yellow Sea, along the Coast of Corea, and through its numerous hitherto undiscovered Islands, etc., etc. By John McLeod, Surgeon of the Alceste. 1 vol., pp. 288 (see pp. 38–53). London, 1877. A witty and lively narrative.

** Voyages along the Coast of China (Corea), etc. By Charles Gutzlaff. 1 vol., pp. 332. New York, 1833. (From July 17, to August 17, 1832; pp. 254–287.) [xix]

* Narrative of the Voyage of H.M.S. Samarang, during the years 1843–46. By Captain Sir E. Belcher. 2 vols. 8vo, pp. 574–378. London, 1848. Vol. i. pp. 324–358; vol. ii., pp. 444–466, relate to Corea.

* American Commerce with China. By Gideon Nye, Esq. In the Far East. Shanghae, 1878. A history of the commercial relations of the United States with China, especially before 1800.

* Diplomatic Correspondence of the United States, China, and Japan, 1866–81.

* Report of the Secretary of the Navy to Congress, pp. 275–313. 1872.

* Private Notes, Charts, and Maps of Officers of the United States Navy who were in Corea in 1871.

** A Summer Dream of ’71. A Story of Corea. By T. G. The Far East. Shanghae, April, 1878.

* Journey through Eastern Mantchooria and Korea. By Walton Grinnell. Journal American Geographical Society, 1870–71, pp. 283–300.

* Japan and Corea. A valuable monograph in six chapters, by Mr. E. H. House, in The Tōkiō Times, 1877.

** On a Collection of Crustacea made in the Corean and Japanese Seas. J. Muirs, 1879. London Zoological Society’s Proceedings (pp. 18–81, pls. 1–113). Reviewed by J. S. Kingsley. Norwich, N. Y. American Naturalist.

** A Private Trip in Corea. By Frank Cowan, M.D. The Japan Mail, 1880.

† The Leading Men of Japan. By Charles Lanman. Boston, 1882. Contains a chapter on Corea.

* Manuscript volume of pencil notes made by Kawamura Kuanshiu, an officer on the Japanese gunboat Unyo-kuan, during her cruise and capture of the Kang-wa Fort, 1875. Partly printed in the Japan Mail.

* Journals of Japanese Military and Diplomatic Officers who have visited Corea, and Correspondence of the Japanese newspapers, from Seoul, Fusan, Gensan, etc. These have been partly translated for the English press at Yokohama.

* Correspondence, Notes, Editorials, etc., in the English and French newspapers published in China and Japan.

** Maru-maru Shimbun (Japanese Punch).

* Chō-sen: Its Eight Administrative Divisions. 1 vol. Tōkiō, Japan, 1882.

* Chō-sen Jijo. A short Account of Corea, its History, Productions, etc. 2 vols. Tōkiō, 1875.

* Chō-sen Bunkenroku (Things Seen and Heard concerning Corea). By Sato Hakushi. 2 vols. Tōkiō, 1875.

* Travels of a Naturalist in Japan [Corea] and Manchuria. By Arthur Adams. 1 vol., pp. 334. London, 1870. See chaps, x., xi., pp. 125–166.

** Ueber die Reise der Kais. Corvette Hertha, in besondere nach Corea. Kramer, Marine Prediger. Zeit. für Ethnologie, 1873. Verhandlungen, pp. 49–54.

** A Forbidden Land. By Ernest Oppert. 1 vol., pp. 349. Illustrations, charts, etc. New York, 1880.

** Journeys in North China. By Rev. A. Williamson. 2 vols. 16mo. London, 1870. Besides a chapter on Corea, this work contains an excellent map of the country north and east of Chō-sen

** The Middle Kingdom. By S. Wells Williams. [xx]

** Consular Reports in the Blue Books of the British Government, especially the Reports of Mr. McPherson, Consul at Niu-chwang. January, 1866.

* Handbook for Central and Northern Japan, with maps and plans. Satow and Hawes. 1 vol. 16mo, pp. 489. This work, which leaves nothing to be desired as a guide-book, contains several references to Corean art and history.

** The Wild Coasts of Nipon. By Captain H. C. St. John (who surveyed some parts of Southern Corea in H.B.M.S. Sylvia). See chap, xii., pp. 235–255, with a map of Corea.

** Darlegung aus der Geschichte und Geographie Coreas. Pfizmaier. 8vo, pp. 56. Vienna, 1874.

† Petermann’s Mittheilungen, No. 1, Carte No. 19, 1871.

** Das Konigreich Korea. Von Kloden. Aus allen Welth., x., Nos. 5 u. 6.

† Corea. Geographical Magazine. (S. Mossman.) vi. p. 148, 1877.

† Corea. By Captain Allen Young, Royal Geographical Society. Vol. ix., No. 6, pp. 296–300.

** China, with an Appendix on Corea. By Charles Eden. 1 vol., pp. 281–322. London. A popular compilation.

** Korea and the Lost Tribes, and Map and Chart of Korea. Text and illustrations. The title of this work is sufficient. Even the bibliography of Corea has a comic side.

** Chi-shima (Kurile Islands) and Russian Invasion. A lecture delivered in Japanese, before the Tōkiō United Geographical Society, February 24, 1882. By Admiral Enomoto. This valuable historical treatise, translated for the Japan Mail and Japan Herald, contains much information about Russian operations in the countries bordering the North Pacific and the Coreans north of the Tumen.

† Bulletin de la Société Geographique, 1875. Corean villages in the Russian possessions described.

** Ravensteins, The Russians on the Amoor. London, 1861.

† Die Insel Quelpart. Deutsche Geogr. Blätter, 1879. iii., No. 1, S. 45–46.

† A Trip to Quelpaert. Nautical Magazine, 1870, No. 4, p. 321–325.

** The Edinburgh Review of 1872, and Fortnightly Review of 1875, contain articles on Corea.

* The Missionary Record of the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland, Edinburgh, containing the Correspondence and Notes of the Missionaries laboring among the Chinese and Coreans, and who have translated the New Testament into Corean.

† La Corée, par M. Paul Tournafond, editor of L’Exploration, a geographical journal published in Paris, which contains frequent notes on Corea.

† La Corée, ses Ressources, son avenir commercial, par Maurice Jametel. L’Economiste Français, Juillet 23, 1881.

* The Japan Herald, The Japan Mail, The Japan Gazette, L’Echo du Japan, of Yokohama, and North China Herald, Shanghae, have furnished much information concerning recent events in Corea.

Corea, the Last of the Hermit Nations. Sunday Magazine, New York, May, 1878.

Corea and the United States. The Independent, New York, Nov. 17, 1881.

Corea, the Hermit Nation. Bulletin of the American Geographical Society, New York, 1881, No. 3. [xxi]

Chautauqua Text-Books, No. 34. Asiatic History; China, Corea, Japan. 16mo, pp. 86. New York, 1881.

Library of Universal Knowledge, articles Corea, Fusan, Gensan, Kang-wa, etc. New York, 1880.

Cyclopædia of Political Science, etc., article Corea. Chicago, 1881.

The Corean Origin of Japanese Art. Century Magazine. December, 1882. By Wm. Elliot Griffis.

ORTHOGRAPHY AND PRONUNCIATION.

In the transliteration of Corean names into English, an attempt has been made to render them in as accurate and simple a manner as is, under the circumstances, possible. The Coreans themselves have no uniform system of spelling proper names, nor do the French missionaries agree in their renderings—as a comparison of their maps and writings shows. Our aim in this work has been to use as few letters as possible.

Japanese words are all pronounced according to the European method—a as in father, é as in prey, e as in men, i as in machine, o as in bone, u as in tune, ŭ as in sun; ai as in aisle, ua as in quarantine, ei as in feign, and iu is sounded as yu; g is always hard; and c before a vowel, g soft, l, q, s used as z, x, and the combinations ph and th are not used. The long vowel, rather diphthong o, or oho, is marked ō.

The most familiar Chinese names are retained in their usual English form.

Corean words are transliterated on the same general principles as the Japanese, though ears familiar with Corean will find the obscure sound between o and short u is written with either of these letters, as Chan-yon, or In-chiŭn, or Kiung-sang. Ch may sometimes be used instead of j; and e where o or a or u might more correctly be used, as in Kang-wen, or Wen-chiu. Instead of the French ou, or ho, we have written W, as in Whang-hai, Kang-wa, rather than Hoang-hai, Kang-hoa, Kang-ouen, Tai-ouen Kun, etc.; and in place of ts we have used ch, as Kwang-chiu rather than Kwang-tsiu, and Wen-chiu than Ouen-tsiu. [xxii]

MAPS AND PLANS.

| PAGE | ||||||||

| Ancestral Seats of the Fuyu Race, | 25 | |||||||

| Sam-han, | 30 | |||||||

| Ancient Japan and Corea, | 56 | |||||||

| The Neutral Territory, | 85 | |||||||

| The Japanese Military Operations of 1592, | 99 | |||||||

| The Campaign in the North, 1592–1593, | 107 | |||||||

| The Operations of the Second Invasion, | 131 | |||||||

| Plan of Uru-san Castle, | 138 | |||||||

| Home of the Manchius and their Migrations, | 155 | |||||||

| The Jesuit Survey of 1709, | 165 | |||||||

| Ping-an Province, | 181 | |||||||

| The Yellow Sea Province, | 185 | |||||||

| The Capital Province, | 188 | |||||||

| Military Geography of Seoul, | 190 | |||||||

| Chung-chong Province, | 194 | |||||||

| Chulla-dō, | 199 | |||||||

| The Province Nearest Japan, | 204 | |||||||

| Kang-wen Province, | 208 | |||||||

| Corean Frontier Facing Manchuria and Russia, | 210 | |||||||

| Southern Part of Ham-kiung, | 215 | |||||||

| The Missionary’s Gateway into Corea, | 364 | |||||||

| Border Towns of Northern Corea, | 365 | |||||||

| The French Naval and Military Operations, 1866, | 379 | |||||||

| Map Illustrating the “General Sherman” Affair, | 393 | |||||||

| Map Illustrating the “China” Affair, | 400 | |||||||

| Map of the American Naval Operations in 1871, | 415 | |||||||

| General Map of Corea at the End of 1906 At end of volume. | ||||||||

[xxiii]

CONTENTS.

PART I.

ANCIENT AND MEDIÆVAL HISTORY.

CHAPTER I. PAGE

The Corean Peninsula, 1

CHAPTER II.

The Old Kingdom of Chō-sen, 11

CHAPTER III.

The Fuyu Race and their Migrations, 19

CHAPTER IV.

Sam-han, or Southern Corea, 30

CHAPTER V.

Epoch of the Three Kingdoms.—Hiaksai, 35

CHAPTER VI.

Epoch of the Three Kingdoms.—Korai, 40

CHAPTER VII.

Epoch of the Three Kingdoms.—Shinra, 45

CHAPTER VIII.

Japan and Corea, 51 [xxiv]

CHAPTER IX.

Korai, or United Corea, 63

CHAPTER X.

Cathay, Zipangu, and the Mongols, 70

CHAPTER XI.

New Chō-sen, 76

CHAPTER XII.

Events Leading to the Japanese Invasion, 88

CHAPTER XIII.

The Invasion—On to Seoul, 95

CHAPTER XIV.

The Campaign in the North, 104

CHAPTER XV.

The Retreat from Seoul, 115

CHAPTER XVI.

Cespedes, the Christian Chaplain, 121

CHAPTER XVII.

Diplomacy at Kiōto and Peking, 124

CHAPTER XVIII.

The Second Invasion, 129

CHAPTER XIX.

The Siege of Uru-san Castle, 137

CHAPTER XX.

Changes after the Invasion, 145

CHAPTER XXI.

The Issachar of Eastern Asia, 154

CHAPTER XXII.

The Dutchmen in Exile, 167 [xxv]

PART II.

POLITICAL AND SOCIAL COREA.

CHAPTER XXIII.

The Eight Provinces, 179

CHAPTER XXIV.

The King and Royal Palace, 218

CHAPTER XXV.

Political Parties, 224

CHAPTER XXVI.

Organization and Methods of Government, 230

CHAPTER XXVII.

Feudalism, Serfdom, and Society, 237

CHAPTER XXVIII.

Social Life—Woman and the Family, 244

CHAPTER XXIX.

Child Life, 256

CHAPTER XXX.

Housekeeping, Diet, and Costume, 262

CHAPTER XXXI.

Mourning and Burial, 277

CHAPTER XXXII.

Out-door Life.—Characters and Employments, 284

CHAPTER XXXIII.

Shamanism and Mythical Zoölogy, 300 [xxvi]

CHAPTER XXXIV.

Legends and Folk-lore, 307

CHAPTER XXXV.

Proverbs and Pithy Sayings, 317

CHAPTER XXXVI.

The Corean Tiger, 320

CHAPTER XXXVII.

Religion, 326

CHAPTER XXXVIII.

Education and Culture, 337

PART III.

MODERN AND RECENT HISTORY.

CHAPTER XXXIX.

The Beginnings of Christianity—1784–1794, 347

CHAPTER XL.

Persecution and Martyrdom—1801–1834, 353

CHAPTER XLI.

The Entrance of the French Missionaries—1835–1845, 361

CHAPTER XLII.

The Walls of Isolation Sapped, 367

CHAPTER XLIII.

The French Expedition, 377

CHAPTER XLIV.

American Relations with Corea, 388 [xxvii]

CHAPTER XLV.

A Body-Snatching Expedition, 396

CHAPTER XLVI.

Our Little War with the Heathen, 403

CHAPTER XLVII.

The Ports Opened to Japanese Commerce, 420

CHAPTER XLVIII.

The Year of the Treaties, 433

CHAPTER XLIX.

The Economic Condition of Corea, 443

CHAPTER L.

Internal Politics: Chinese and Japanese, 458

CHAPTER LI.

The War of 1894: Corea an Empire, 472

CHAPTER LII.

Japan and Russia in Conflict, 484

CHAPTER LIII.

Corea a Japanese Protectorate, 497

CHAPTER LIV.

Chō-sen: A Province of Japan, 507

INDEX, 521 [xxix]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| PAGE | ||||||||

| A City in Corea, | Frontispiece. | |||||||

| Corean Coin, | 10 | |||||||

| Coin of Modern Chō-sen, | 18 | |||||||

| The Founder of Fuyu Crossing the Sungari River, | 20 | |||||||

| Coin of the Sam-han, or the Three Kingdoms, | 34 | |||||||

| Coin of Korai, | 69 | |||||||

| Two-masted Corean Vessel, | 75 | |||||||

| The Walls of Seoul, | 79 | |||||||

| Magistrate and Servant, | 81 | |||||||

| Corean Knight of the Sixteenth Century, | 101 | |||||||

| Styles of Hair-dressing in Corea, | 161 | |||||||

| A Pleasure-party on the River, | 196 | |||||||

| Corean Village in Russian Territory, | 211 | |||||||

| Table Spread for Festal Occasions, | 264 | |||||||

| Gentlemen’s Garments and Dress Patterns, | 275 | |||||||

| Thatched House near Seoul, | 282 | |||||||

| Battle-flag Captured by the Americans in 1871, | 305 | |||||||

| Battle-flag Captured in the Han Forts, 1871, | 320 | |||||||

| House and Garden of a Noble, | 355 | |||||||

| Breech-loading Cannon of Corean Manufacture, | 382 | |||||||

| The Entering Wedge of Civilization, | 407 | |||||||

[xxxi]

I.

ANCIENT AND MEDIÆVAL HISTORY

[1]

COREA:

THE HERMIT NATION.

CHAPTER I.

THE COREAN PENINSULA.

Corea, though unknown even by name in Europe until the sixteenth century, was the subject of description by Arab geographers of the middle ages. Before the peninsula was known as a political unit, the envoys of Shinra, one of the three Corean states, and those from Persia met face to face before the throne of China. The Arab merchants trading to Chinese ports crossed the Yellow Sea, visited the peninsula, and even settled there. The youths of Shinra, sent by their sovereign to study the arts of war and peace at Nanking, the mediæval capitol of China, may often have seen and talked with the merchants of Bagdad and Damascus. The Corean term for Mussulmans is hoi-hoi, “round and round” men. Corean art shows the undoubted influence of Persia.

A very interesting passage in the chronicles of Japan, while illustrating the sensitive regard of the Japanese for the forms of etiquette, shows another point of contact between Corean and Saracen civilization. It occurs in the Nihon O Dai Ichi Ran, or “A View of the Imperial Family of Japan.” “In the first month of the sixth year of Tempiō Shōhō [February, 754 A.D.], the Japanese nobles Ohan no Komaro and Kibi no Mabi returned from China, in which country they had left Fujiwara no Seiga. The former reported that at the audience which they had of the Emperor Gen-sho, on New Tear’s Day [January 18th], the ambassadors [2]of Towan [Thibet] occupied the first place to the west, those from Shinra the first place to the east, and that the second place to the west had been destined for them (the Japanese envoys), and the second place to the east for the ambassadors of the Kingdom of Dai Shoku [Persia, then part of the empire of the Caliphs]. Komaro, offended with this arrangement, asked why the Chinese should give precedence over them to the envoys of Shinra, a state which had long been tributary to Japan. The Chinese officials, impressed alike with the firmness and displeasure exhibited by Komaro, assigned to the Japanese envoys a place above those of Persia and to the envoys of Shinra a place above those of Thibet.”

Thus the point at issue was settled, by avoiding it, and assigning equal honor to Shinra and Japan.

This incident alone shows that close communications were kept up between the far east and the west of Asia, and that Corea was known beyond Chinese Asia. At that time the boundaries of the two empires, the Arab and the Chinese, touched each other.

The first notice of Corea in western books or writings occurs in the works of Khordadbeh, an Arab geographer of the ninth century, in his Book of Roads and Provinces. He is thus quoted by Richthofen in his work on China (p. 575, note):

“What lies on the other side of China is unknown land. But high mountains rise up densely across from Kantu. These lie over in the land of Sila, which is rich in gold. Mussulmans who visit this country often allow themselves, through the advantages of the same, to be induced to settle here. They export from thence ginseng, deerhorn, aloes, camphor, nails, saddles, porcelain, satin, zimmit (cinnamon?) and galanga (ginger?).”

Richthofen rightly argues that Sila is Shinra and Kantu is the promontory province of Shantung. This Arabic term “Sila” is a corruption of Shinra—the predominant state in Corea at the time of Khordadbeh.

The name of this kingdom was pronounced by the Japanese, Shinra, and by the Chinese, Sinlo—the latter easily altered in Arabic mouths to Sila.

The European name Corea is derived from the Japanese term Korai (Chinese Kaoli), the name of another state in the peninsula, rival to Shinra. It was also the official title of the nation from the eleventh to the fourteenth century. The Portuguese, who were the first navigators of the Yellow Sea, brought the name to Europe, calling the country Coria, whence the English Corea. [3]

The French Jesuits at Peking Gallicized this into Corée. Following the genius of their language, they call it La Corée, just as they speak of England as L’Angleterre, Germany as L’Allemagne, and America as L’Amérique. Hence has arisen the curious designation, used even by English writers, of this peninsula as “the Corea.” But what is good French in this case is very bad English, and we should no more say “the Corea” than “the Germany,” “the England,” or “the America.” English usage forbids the employment of the definite article before a proper name, and those writers who persist in prefixing the definite article to the proper name Corea are either ignorant of the significance of the word, or knowingly violate the laws of the English language. The native name of the country is Chō-sen (Morning Calm or Fresh Morning), which French writers, always prodigal in the use of vowels, spell Tsio-sen, Teo-cen, or Tchao-sian. The Chinese call it Tung-kwo (Eastern Kingdom), and the Manchius, Sol-ho or Solbo.

The peninsula, with its outlying islands, is nearly equal in size to Minnesota or to Great Britain. Its area is between eighty and ninety thousand square miles. Its coast line measures 1,740 miles. In general shape and relative position to the Asian Continent it resembles Florida. It hangs down between the Middle Kingdom and the Sunrise Land, separating the sea of Japan and the Yellow Sea, between the 34th and 43d parallels of north latitude. In its general configuration, when looked at from the westward on a good map, especially the magnificent one made by the Japanese War Department, Chō-sen resembles the outspread wings of a headless butterfly, the lobes of the wings being toward China, and their tops toward Japan.

Legend, tradition, and geological indications lead us to believe that anciently the Chinese promontory and province of Shantung and the Corean peninsula were connected, and that dry land once covered the space filled by the waters joining the Gulf of Pechili and the Yellow Sea. These waters are so shallow that the elevation of their bottoms but a few feet would restore their area to the land surface of the globe. On the other side, also, the sea of Japan is very shallow, and the straits of Corea, at their greatest depth, have but eighty-three feet of water. That portion of the Chinese province of Shing King, or Southern Manchuria, bordering the sea, is a great plain, or series of flats elevated but a few feet above tide water, which becomes nearly impassable during heavy rains.

A marked difference is noted between the east and west coasts [4]of the peninsula. The former is comparatively destitute of harbors, and the shore is high, monotonous, and but slightly indented or fringed with islands. It contains but three provinces. On the west coast are five provinces, and the sea is thickly strewn with islands, harbors and landing places, while navigable rivers are more numerous. The “Corean Archipelago” contains an amazing number of fertile and inhabited islands and islets rising out of deep water. They are thus described by the naturalist Arthur Adams:

“Leaving the huge, cone-like island of Quelpaert in the distance, the freshening breeze bears us gallantly toward those unknown islands which form the Archipelago of Korea. As you approach them you look from the deck of the vessel and you see them dotting the wide, blue, boundless plain of the sea—groups and clusters of islands stretching away into the far distance. Far as the eye can reach, their dark masses can be faintly discerned, and as we close, one after another, the bold outlines of their mountain peaks stand out clearly against the cloudless sky. The water from which they seem to arise is so deep around them that a ship can almost range up alongside them. The rough, gray granite and basaltic cliffs, of which they are composed, show them to be only the rugged peaks of submerged mountain masses which have been rent, in some great convulsion of nature, from the peninsula which stretches into the sea from the main land. You gaze upward and see the weird, fantastic outline which some of their torn and riven peaks present. In fact, they have assumed such peculiar forms as to have suggested to navigators characteristic names. Here, for example, stands out the fretted, crumbling towers of one called Windsor Castle, there frowns a noble rock-ruin, the Monastery, and here again, mounting to the skies, the Abbey Peak.

“Some of the islands of this Archipelago are very lofty, and one was ascertained to boast of a naked granite peak more than two thousand feet above the level of the sea. Many of the summits are crowned with a dense forest of conifers, dark trees, very similar in appearance to Scotch firs.”

The king of Corea may well be called “Sovereign of Ten Thousand Isles.”

Almost the only striking feature of the inland physical geography of Chō-sen, heretofore generally known, is that chain of mountains which traverses the peninsula from North to South, not in a straight line, but in an exceedingly sinuous course, similar to the [5]tacking of a ship when sailing in the eye of the wind. As the Coreans say, “it winds out and in ninety-nine times.”

Striking out from Manchuria it trends eastward to the sea at Cape Bruat on the 41st parallel, thence it strikes southwest about eighty miles to the region west of Broughton’s Bay (the narrowest part of Corea), whence it bears westward to the sea at the 37th parallel, or Cape Pelissier, where its angle culminates in the lofty mountain peaks named by the Russians Mount Popoff—after the inventor of the high turret ships. From this point it throws off a fringe of lesser hills to the southward while the main chain strikes southwest, and after forming the boundary between two most southern provinces reaches the sea near the Amherst Isles. Nor does its course end here, for the uncounted islands of the Archipelago, with their fantastic rock-ruins and perennial greenery, that suggest deserted castles and abbeys mantled with ivy, are but the wave-worn and shattered remnants of this lordly range.

This chief feature in the physical geography of the peninsula determines largely its configuration, climate, river system and watershed, political divisions, and natural barriers. Speaking roughly, Eastern Corea is a mountainous ridge of which Western Corea is but the slope.

No river of any importance is found inside the peninsula east of these mountains, except the Nak-tong, which drains the valley formed by the interior and the sea-coast ranges, while on the westward slope ten broad streams collect the tribute of their melted snows to enrich the valleys of five provinces.

Through seven parallels of latitude this range fronts the sea of Japan with a coast barrier which, except at Yung-hing Bay, is nearly destitute of harbors. Its timbered heights present a wall of living green to the mariner sailing from Vladivostok to Shanghai.

Great differences of climate in the same latitude are observed on opposite sides of this mountain range, which has various local epithets. From their height and the permanence of their winter covering, the word “white” forms an oft-recurring part of their names.

The division of the country into eight dō, or provinces, which are grouped in southern, central, and northern, is based mainly on the river basins. The rainfall in nearly every province finds an outlet on its own sea-border. Only the western slopes of the two northeastern provinces are exceptions to this rule, since they discharge part of their waters into streams emptying beyond their [6]boundaries. The Yalu, and the Han—“the river”—are the only streams whose sources lie beyond their own provinces. In rare instances are the rivers known by the same word along their whole length, various local names being applied by the people of different neighborhoods. On the maps in this work only the name most commonly given to each stream near its mouth is printed.

In respect to the sea basins, three provinces on the west coast form one side of the depression called the Yellow Sea Basin, of which Northeastern China forms the opposite rim. The three eastern dō, or circuits, lining the Sea of Japan, make the concave in the sea basin to which Japan offers the corresponding edge. The entire northern boundary of the peninsula from sea to gulf, except where the colossal peak Paik-tu (‘White Head’) forms the water-shed, is one vast valley in which lie the basins of the Yalu and Tumen.

Corea is, in reality, an island, as the following description of White Head Mountain, obtained from the Journal of the Chinese Ambassador to Seoul, shows. This mountain has two summits, one facing north, the other east. On the top is a lake thirty ri around. In shape the peak is that of a colossal white vase open to the sky, and fluted or scolloped round the edge like the vases of Chinese porcelain. Its crater, white on the outside, is red, with whitish veins, inside. Snow and ice clothe the sides, sometimes as late as June. On the side of the north, there issues a runnel, a yard in depth, which falls in a cascade and forms the source of the (Tumen) river. Three or four ri from the summit of the mountain the stream divides into two parts; one is the source of the Yalu River.

In general, it may be said to dwellers in the temperate zone that the climate of Corea is excellent, bracing in the north, and in the south tempered by the ocean breezes of summer. The winters in the higher latitudes are not more rigorous than in the State of New York; while, in the most southern, they are as delightful as those in the Carolinas. In so mountainous and sea-girt a country there are, of course, great climatic varieties even in the same provinces.

As compared with European countries of the same latitude, Corea is much colder in winter and hotter in summer. In the north, the Tumen River is usually frozen during five months in the year. The Han River at Seoul may be crossed on ice during two or three months. Even in the southern provinces, deep snows cover the mountains, though the plains are usually free, rarely [7]holding the snow during a whole day. The lowest point to which the mercury fell, in the observation of the French missionaries, was at the 35th parallel of latitude 8° and at the 37th parallel 15° (F.). The most delightful seasons in the year are spring and autumn. In summer, in addition to the great heat, the rain falls often in torrents that blockade the roads and render travelling and transport next to impossible. Toward the end of September occurs the period of tempests and variable winds.

A glance at the fauna of Corea suggests at once India, Europe, Massachusetts, and Florida. In the forests, especially of the two northern circuits, tigers of the largest size and fiercest aspect abound. When food fails them, they attack human habitations, and the annual list of victims is very large. The leopard is common. There are several species of deer, which furnish not only hides and venison, but horns which, when “in velvet,” are highly prized as medicine. In the fauna are included bears, wild hogs and the common pigs of stunted breed, wild cats, badgers, foxes, beavers, otters, several species of martens. The salamander is found in the streams, as in western Japan.

Of domestic beasts, horses are very numerous, being mostly of a short, stunted breed. Immense numbers of oxen are found in the south, furnishing the meat diet craved by the people who eat much more of fatty stuff than the Japanese.

Goats are rare. Sheep are imported from China only for sacrificial purposes. The dog serves for food as well as for companionship and defence. Of birds, the pheasant, falcon, eagle, crane, and stork, are common.

Corea has for centuries successfully carried out the policy of isolation. Instead of a peninsula, her rulers have striven to make her an inaccessible island, and insulate her from the shock of change. She has built not a Great Wall of masonry, but a barrier of sea and river-flood, of mountain and devastated land, of palisades and cordons of armed sentinels. Frost and snow, storm and winter, she hails as her allies. Not content with the sea-border she desolates her shores lest they tempt the mariner to land. Between her Chinese neighbor and herself, she has placed a neutral space of unplanted, unoccupied land. This strip of forests and desolated plains, twenty leagues wide, stretches between Corea and Manchuria. To form it, four cities and many villages were suppressed three centuries ago, and left in ruins. The soil of these solitudes is very good, the roads easy, and the hills not high. [8]

For centuries, only the wild beasts, fugitives from justice, and outlaws from both countries, have inhabited this fertile but forbidden territory. Occasionally, borderers would cultivate portions of it, but gather the produce by night or stealthily by day, venturing on it as prisoners would step over the “dead line.” Of late years, the Chinese Government has respected the neutrality of this barrier less and less. One of those recurring historical phenomena peculiar to Manchuria—the increase and pressure of population—has within a generation caused the occupation of large portions of this neutral strip. Parts of it have been surveyed and staked out by Chinese surveyors, and the Corean Government has been too feeble to prevent the occupation. Though no towns or villages are marked on the map of this “No-man’s land,” yet already, a considerable number of small settlements exist upon it.

As this once neutral territory is being gradually obliterated, so the former lines of palisades and stone walls on the northern border which, two centuries and more ago, were strong, high, guarded and kept in repair, have year by year, during a long era of peace, been suffered to fall into decay. They exist no longer, and should be erased from the maps.

The pressure of population in Manchuria upon the Corean border is a portentous phenomenon. For Manchuria, which for ages past has, like a prolific hive, swarmed off masses of humanity into other lands, seems again preparing to send off a fresh cloud. Already her millions press upon her neighbors for room.

The clock of history seems once more about to strike, perhaps to order again another dynasty on the oft-changed throne of China.

From mysterious Mongolia, have gone out in the past the various hordes called Tartars, or Tâtars, Huns, Turks, Kitans, Mongols, Manchius. Perhaps her loins also are already swelling with a new progeny. This marvellous region gave forth the man-children who destroyed the Roman Empire; who extinguished Christianity in Asia and Africa, and nearly in Europe; who, after conquering India and China threatened Christendom, and holding Russia for two centuries, created the largest empire ever known on earth; and finally reared “the most improvable race in Asia” that now holds the throne and empire of China.

Chō-sen since acting the hermit policy of ancient Egypt and mediæval China, has preserved two loopholes at Fusan and Ai-chiu, the former on the sea toward Japan, and the latter in the northwest, on the Chinese border. What in time of peace is a needle’s [9]eye, is in time of war a flood-gate for enemies. From the west, the invading armies of China have again and again marched around over the Gulf of Liao Tung and entered the peninsula to plunder and to conquer, while Chinese fleets from Shan-tung have over and over again arched their sails in the Yellow Sea to furl them again in Corean Rivers. From the east, the Japanese have pushed across the sea to invade Corea as enemies, to help as allies against China, to levy tribute and go away enriched, or anon to send their grain-laden ships to their starving neighbors.

From a political point of view the geographical position of this country is most unfortunate. Placed between two rival nations, aliens in blood, temper, and policy, Chō-sen has been the rich grist between the upper and nether millstones of China and Japan. Out of the north, rising from the vast plains at Manchuria, the conquering hordes, on their way to the prize lying south of the Great Wall, have over and over again descended on Corean soil to make it their granary. From the pre-historic forays of the tribes beyond the Sungari, to the last new actors on the scene, the Russians, who stand with their feet on the Tumen, looking over the border on her helpless neighbor, Corea has been threatened or devastated by her eager enemies.

Nevertheless Corea has always remained Corea, a separate country; and the people are Coreans, more allied to the Japanese than the Chinese, yet in language, politics, and social customs, different from either. As Ireland is not England or Scotland, neither is Chō-sen China nor Japan.

In her boasted history of “four thousand years,” the little kingdom has too often been the Ireland of China, so far as misgovernment on the one side, and fretful and spasmodic resistance on the other, are considered. Yet ancient Corea has also been an Ireland to Japan, in the better sense of giving to her the art, letters, science, and ethics of continental civilization. As of old, went forth from Tara’s halls to the British Isles and the continent, the bard and the monk to elevate and civilize Europe with the culture of Rome and the religion of Christianity, so for centuries there crossed the sea from the peninsula a stream of scholars, artists, and missionaries who brought to Japan the social culture of Chō-sen, the literature of China, and the religion of India. A grateful bonze of Japan has well told the story of Corea’s part in the civilization of his native country in a book entitled “Precious Jewels from a Neighbor Country.” [10]

Corea fulfils one of the first conditions of national safety in having “scientific frontiers,” or adequate natural boundaries of river, mountain, and sea. But now what was once barrier is highway. What was once the safety of isolation, is now the weakness of the recluse. Steam has made the water a surer path than land, and Japan, once the pupil and anon the conqueror of the little kingdom, has in these last days become the helpful friend of Corea’s people, and the opener of the long-sealed peninsula.

Already the friendly whistle of Japanese steamers is heard in the harbors of two ports in which are trading settlements. At Fusan and Gensan, the mikado’s subjects hold commercial rivalry with the Coreans, and through these two loopholes the hermits of the peninsula catch glimpses of the outer world that must waken thought and create a desire to enter the family of nations. The ill fame of the native character for inhospitality and hatred of foreigners belongs not to the people, nor is truly characteristic of them. It inheres in the government which curses country and people, and in the ruling classes who, like those in Old Japan, do not wish the peasantry to see the inferiority of those who govern them.

Corea cannot long remain a hermit nation. The near future will see her open to the world. Commerce and pure Christianity will enter to elevate her people, and the student of science, ethnology, and language will find a tempting field on which shall be solved many a yet obscure problem. The forbidden land of to-day is, in many striking points of comparison, the analogue of Old Japan. While the last of the hermit nations awaits some gallant Perry of the future, we may hope that the same brilliant path of progress on which the Sunrise Kingdom has entered, awaits the Land of Morning Calm.

We add a postscript. As our manuscript turns to print, we hear of the treaty successfully negotiated by Commodore Shufeldt.

Corean Coin—“Eastern Kingdom, Precious Treasure.”

[11]

CHAPTER II.

THE OLD KINGDOM OF CHŌ-SEN.

Like almost every country on earth, whose history is known, Corea is inhabited by a race that is not aboriginal. The present occupiers of the land drove out or conquered the people whom they found upon it. They are the descendants of a stock whose ancestral seats were beyond those ever white mountains which buttress the northern frontier.

Nevertheless, for the origins of their national history, we must look to one whom the Coreans of this nineteenth century still call the founder of their social order. The scene of his labors is laid partly within the peninsula, and chiefly in Manchuria, on the well watered plains of Shing-king, formerly called Liao Tung.

The third dynasty of the thirty-three or thirty-four lines of rulers who have filled the oft-changed throne of China, is known in history as the Shang (or Yin). It began B.C. 1766, and after a line of twenty-eight sovereigns, ended in Chow Sin, who died B.C. 1122. He was an unscrupulous tyrant, and has been called “the Nero of China.”

One of his nobles was Ki Tsze, viscount of Ki (or Latinized, Kicius). He was a profound scholar and author of important portions of the classic book, entitled the Shu King. He was a counsellor of the tyrant king, and being a man of upright character, was greatly scandalized at the conduct of his licentious and cruel master.

The sage remonstrated with his sovereign hoping to turn him from his evil ways. In this noble purpose he was assisted by two other men of rank named Pi Kan and Wei Tsze. All their efforts were of no avail, and finding the reformation of the tyrant hopeless, Wei Tsze, though a kinsman of the king, voluntarily exiled himself from the realm, while Pi Kan, also a relative of Chow Sin, was cruelly murdered in the following manner:

The king, mocking the wise counsellor, cried out, “They say [12]that a sage has seven orifices to his heart; let us see if this is the case with Pi Kan.” This Chinese monarch, himself so much like Herod in other respects, had a wife who in her character resembled Herodias. It was she who expressed the bloody wish to see the heart of Pi Kan. By the imperial order the sage was put to death and his body ripped open. His heart, torn out, was brought before the cruel pair. Ki Tsze, the third counsellor, was cast into prison.

Meanwhile the people and nobles of the empire were rising in arms against the tyrant whose misrule had become intolerable. They were led on by one Wu Wang, who crossed the Yellow River, and met the tyrant on the plains of Muh. In the great battle that ensued, the army of Chow Sin was defeated. Escaping to his palace, and ordering it to be set on fire, he perished in the flames.

Among the conqueror’s first acts was the erection of a memorial mound over the grave of Pi Kan, and an order that Ki Tsze should be released from prison, and appointed Prime Minister of the realm.

But the sage’s loyalty exceeded his gratitude. In spite of the magnanimity of the offer, Ki Tsze frankly told the conqueror that duty to his deposed sovereign forbade him serving one whom he could not but regard as a usurper. He then departed into the regions lying to the northeast. With him went several thousand Chinese emigrants, mostly the remnant of the defeated army, now exiles, who made him their king. It is not probable that in his distant realm he received investment from or paid tribute to King Wu. Such an act would be a virtual acknowledgment of the righteousness of rebellion and revolution. It would prove that the sage forgave the usurper. Some Chinese historians state that Ki Tsze accepted a title from Wu Wang. Others maintain that the investiture “was a euphemism to shield the character of the ancestor of Confucius.” The migration of Ki Tsze and his followers took place 1122 B.C.

Ki Tsze began vigorously to reduce the aboriginal people of his realm to order. He policed the borders, gave laws to his subjects, and gradually introduced the principles and practice of Chinese etiquette and polity throughout his domain. Previous to his time the people lived in caves and holes in the ground, dressed in leaves, and were destitute of manners, morals, agriculture and cooking, being ignorant savages. The divine being, Dan Kun, had partially civilized them, but Kishi, who brought 5,000 Chinese colonists with [13]him, taught the aborigines letters, reading and writing, medicine, many of the arts, and the political principles of feudal China. The Japanese pronounce the founder’s name Kishi, and the Coreans Kei-tsa or Kysse.

The name conferred by Kishi, the civilizer, upon his new domain is that now in use by the modern Coreans—Chō-sen or Morning Calm.

This ancient kingdom of Chō-sen, according to the Coreans, comprised the modern Chinese province of Shing-king, which is now about the size of Ohio, having an area of 43,000 square miles, and a population of 8,000,000 souls. It is entirely outside and west of the limits of modern Corea.

In addition to the space already named, the fluctuating boundaries of this ancient kingdom embraced at later periods much territory beyond the Liao River toward Peking, and inside the line now marked by the Great Wall. To the east the modern province of Ping-an was included in Chō-sen, the Ta-tong River being its most stable boundary. “Scientific frontiers,” though sought for in those ancient times, were rather ideal than hard and fast. With all due allowance for elastic boundaries, we may say that ancient Chō-sen lay chiefly within the Liao Tung peninsula and the Corean province of Ping-an, that the Liao and the Ta-tong Rivers enclosed it, and that its northern border lay along the 42d parallel of latitude.

The descendants of Ki Tsze are said to have ruled the country until the fourth century before the Christian era. Their names and deeds are alike unknown, but it is stated that there were forty-one generations, making a blood-line of eleven hundred and thirty-one years. The line came to an end in 9 A.D., though they had lost power long before this time.

By common consent of Chinese and native tradition, Ki Tsze is the founder of Corean social order. If this tradition be true, the civilization of the hermit nation nearly equals, in point of time, that of China, and is one of the very oldest in the world, being contemporaneous with that of Egypt and Chaldea. It is certain that the natives plume themselves upon their antiquity, and that the particular vein of Corean arrogance and contempt for western civilization is kindred to that of the Hindoos and Chinese. From the lofty height of thirty centuries of tradition, which to them is unchallenged history, they look with pitying contempt upon the upstart nations of yesterday, who live beyond the sea under some other heaven. When the American Admiral, John Rodgers, in [14]1871, entered the Han River with his fleet, hoping to make a treaty, he was warned off with the repeated answer that “Corea was satisfied with her civilization of four thousand years, and wanted no other.” The perpetual text of all letters from Seoul to Peking, of all proclamations against Christianity, of all death-warrants of converts, and of the oft-repeated refusals to open trade with foreigners is the praise of Ki Tsze as the founder of the virtue and order of “the little kingdom,” and the loyalty of Corea to his doctrines.

In the letter of the king to the Chinese emperor, dated November 25, 1801, the language following the opening sentence is as given below:

“His Imperial Majesty knows that since the time when the remnants of the army of the Yin dynasty migrated to the East [1122 B.C.], the little kingdom has always been distinguished by its exactness in fulfilling all that the rites prescribe, justice and loyalty, and in general by fidelity to her duties,” etc., etc.

In a royal proclamation against the Christian religion, dated January 25, 1802, occurs the following sentence:

“The kingdom granted to Ki Tsze has enjoyed great peace during four hundred years [since the establishment of the ruling dynasty], in all the extent of its territory of two thousand ri and more,” etc.

These are but specimens from official documents which illustrate their pride in antiquity, and the reverence in which their first law giver is held by the Coreans.

Nevertheless, though Kishi may possibly be called the founder of ancient Chō-sen, and her greatest legislator, yet he can scarcely be deemed the ancestor of the people now inhabiting the Corean peninsula. For the modern Coreans are descended from a stock of later origin, and quite different from the ancient Chō-senese. From Ki Tsze, however, sprang a line of kings, and it is possible that his blood courses in some of the noble families of the kingdom.

As the most ancient traditions of Japan and Corea are based on Chinese writings, there is no discrepancy in their accounts of the beginning of Chō-sen history.

Ki Tsze and his colonists were simply the first immigrants to the country northeast of China, of whom history speaks. He found other people on the soil before him, concerning whose origin nothing is known in writing. The land was not densely populated, but of their numbers, or time of coming of the aborigines, or [15]whether of the same race as the tribes in the outlying islands of Japan, no means yet in our power can give answer.

Even the story of Ki Tsze, when critically examined, does not satisfy the rigid demands of modern research. Mayers, in his “Chinese Reader’s Manual” (p. 369), does not concede the first part of the Chow dynasty (1122 B.C.–255 A.D.) to be more than semi-historical, and places the beginning of authentic Chinese history between 781 and 719 B.C., over four centuries after Ki Tsze’s time. Ross (p. 11) says that “the story of Kitsu is not impossible, but it is to be received with suspicion.” It is not at all improbable that the Chō-sen of Ki Tsze’s founding lay in the Sungari valley, and was extended southward at a later period.

It is not for us to dissect too critically the tradition concerning the founder of Corea, nor to locate exactly the scene of his labors. Suffice it to say that the general history, prior to the Christian era, of the country whose story we are to tell, divides itself into that of the north, or Chō-sen, and that of the south, below the Ta-tong River, in which region three kingdoms arose and flourished, with varying fortunes, during a millennium.

We return now to the well-established history of Chō-sen. The Great Wall of China was built by Cheng, the founder of the Tsin dynasty (B.C. 255–209), who began the work in 239 A.D. Before his time, China had been a feudal conglomerate of petty, warring kingdoms. He, by the power of the sword, consolidated them into one homogeneous empire and took the title of the “First Universal Emperor” (Shi Whang Ti). Not content with sweeping away feudal institutions, and building the Great Wall, he ordered all the literary records and the ancient scriptures of Confucius to be destroyed by fire. Yet the empire, whose perpetuity he thought to secure by building a rampart against the barbarians without, and by destroying the material for rebellious thought within, fell to pieces soon after, at his death, when left to the care of a foolish son, and China was plunged into bloody anarchy again.

One of these petty kingdoms that arose on the ruins of the empire was that of Yen, which began to encroach upon its eastern neighbor Chō-sen.

In the later days of the Ki Tsze family, great anarchy prevailed, and the last kings of the line were unable to keep their domain in order, or guard its boundaries.

Taking advantage of its weakness, the king of Yen began boldly and openly to seize upon Chō-sen territory, annexing thousands of [16]square miles to his own domain. By a spasmodic effort, the successors of Ki Tsze again became ascendant, reannexing a large part of the territory of Yen, and receiving great numbers of her people, who had fled from civil war in China, within the borders of Chō-sen for safety and peace.

Thus the spoiler was spoiled, but, later on, the kingdom of Yen was again set up, and the rival states fixed their boundaries and made peace. The Han dynasty in B.C. 206 claimed the imperial power, and sent a summons to the king of Yen to become vassal. On his refusing, the Chinese emperor despatched an army against him, defeated his forces in battle, extinguished his dynasty, and annexed his kingdom.

One of the survivors of this revolt, named Wei-man, with one thousand of his followers, fled to the east. Dressing themselves like wild savages they entered Chō-sen, pretending, with Gibeonitish craft, that they had come from the far west, and begged to be received as subjects.

Kijun, the king, like another Joshua, believing their professions, welcomed them and made their leader a vassal of high rank, with the title of ‘Guardian of the Western Frontier.’ He also set apart a large tract of land for his salary and support.